Duna (language)

| Duna | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

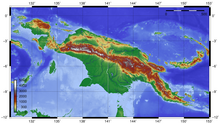

Papua New Guinea ( Southern Highlands ) | |

| speaker | 25,000 | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-3 |

duc |

|

Duna is a Papuan language from Papua New Guinea (also known as Yuna ). It belongs to the Trans New Guinea language family and is often further classified as Duna-Pogaya, as Bogaya appears to be Duna’s closest relative, as evidenced by the similar development of the personal pronouns. The number of speakers is estimated at 11,000 (1991) to 25,000 (2002).

Language context

The people of the Duna

Duna is the native language of the Duna people of the same name who live in the north-western region of the Southern Highlands Province . Most of the Duna are farmers, with sweet potatoes being a staple food alongside other crops and vegetables.

Language influences

| Duna | Tok Pisin | English |

|---|---|---|

| pʰɛkɛtɛɾi | fekteri | "factory" |

| t̪ʰukuɺi | skul | "school" |

| kɔⁿdaɾɛkɛ | contr | "contract" |

| ᵐbuku / a | baked | "book" |

The late contact with the Europeans means that languages such as English have so far had little influence on Duna. Due to cultural influences, however, there are more and more loanwords in the lexical vocabulary of the Duna, mainly from English or the English-related Tok Pisin . However, with the introduction of English as a school language, the influence of English is increasing.

Tok Pisin is the official language in the northern mainland and is therefore also used by the Duna to communicate with outsiders. The language skills range from passive understanding to business fluency, mostly for people who have spent some time outside the Duna community. The status of Tok Pisin has already led to some variations in which words from the Tok Pisin are recognized as alternatives to Duna constructions, such as: B. siriki , which means "to trick", which is used instead of the adjunct construction with ho with the same meaning.

The close contact to the Huli had the greatest influence on Duna so far, so that the Duna of the north-western region clearly delimit the dialect close to the Huli of the south-eastern region, which are closer to the Huli. The influence can be identified using phonetic and lexical variations. There are many synonym sets in Duna where a variant is very likely derived from Huli words: yu and ipa both mean "water, liquid", with / ipa / being an identical word in Huli.

Phonology

The syllable structure in Duna is (C) V (V). There are no consonant clusters, so loanwords derived from words with consonant clusters, as in fa ct ory , are matched by inserting vowels between the consonants.

Consonants

Duna's consonant system consists of twenty consonantic phonemes , including some allophonic variations. Plosives are divided into three articulations according to aspiration and voicing / prenasalization .

| Bilabial | Apical | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirated plosive | pʰ | t̪ʰ | kʰ | kʰʷ | |||

| Plosive | p | t̪ | k | kʷ | |||

| Prenasalized plosive | ᵐb | ⁿd | ᵑɡ | ᵑɡʷ | |||

| nasal | m | n | |||||

| Tap | ɾ | ||||||

| Lateral flap | ɺ | ||||||

| Fricative | H | H | |||||

| glide | w | j | |||||

Vowels

There are five phonemically distinctive vowels.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i | u | |

| center | ɛ | ɔ | |

| Deep | a |

In VV sequences the second V can be a distinctive vowel or a sliding sound / ai / "who" with [ai] or [aj].

Sounds

| case | Rise | Convex | Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"shore" |

- |

"origin" |

"be leisurely" |

|||

"spell" |

"lie" |

- | - |

Duna has four contrasting tones for distinguishing lexical roots. It applies that “the word as a whole is more important than the syllable as a domain for the assignment of tones”. A falling tone is characteristic of the fall contour and a rising tone is characteristic of the rise contour. With the convex contour, the tone rises before falling. The level contour shows no change in tone. Depending on the number of syllables in a word, the contour is lengthened or shortened.

Word classes

pronoun

There are pronouns for the features singular , plural and dual . The third person in the subject position or in possessive constructions is often clitized on noun phrases . "Exclusive identity" can be indicated to subjects with the morpheme -nga - this indicates that the subject is performing the action itself or reflexively. The same effect can be achieved by doubling the pronouns.

| Singular | dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | no | keno | inu |

| 2 | ko | nako | inu |

| 3 | kho | kheno | khunu |

For "Contrastive Subjects" special pronouns are used, which differ from simple pronouns mainly in the vowel: a instead of o . The suffix -ka is the compositional form that acts as a marker for "contrastive subject" in nouns. "Contrastive subjects" either indicate a focus that differentiates old and new or unexpected subjects from other participants, or works like the ergative to emphasize the subject.

| Singular | dual | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | n / A | kena (-ka) |

| 2 | ka | naka |

| 3 | kha | khena (-ka) |

noun

A sentence can contain unmarked, indefinite, generic noun phrases that only have a single constituent:

| wi | kiti-rane |

| game.animal | descend-SW.SEQ |

| "Game animals came down" | |

The suffix -ne can be used to nominalize adjectives. The nominalizer -ne is also used for the nominalization of verbs , but the habitual verbal inflection -na is required beforehand . This composition has roughly the meaning of "for the purpose of".

| Adjectival nominalization: | Verbal nominalization: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Possessive relations are represented by juxtaposing noun phrases or by the postposition -ya "benefaktiv (BEN)". The possessee follows the possessor.

| Possessive with noun phrases: | Possessive with post position: | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

Verbs

Duna has three verb classes: "consonantal verbs" consist of a consonant and the vowel / a / in the a -base form. These are mainly verbs of movement, existentiality and dynamic activities. The " wa -class" verbs mostly contain the morphemes wa or among others in the a -base form. In contrast to regular verbs, these classes require vowel changes in different inflection processes and they can take verb adjuncts. With regular verbs, only affixes are concatenated for the inflection.

The basic morphological structure of the verbs is as follows:

| NEG - | Verb root - | Modifier - | NEG - | Flexion morphology |

Negation is expressed with the circumfix na- -ya , which encloses the verb root (in verb serializations all verb roots are enclosed).

Verb modifier

Adding derivation suffixes or directional demonstratives expands the meaning of the verb. Directional demonstratives like sopa "below" or roma "above" give direction to the action. Adverbial-like modifiers express aspects such as exhaustiveness ( -ku "completeness"), circularity ( -yare "encircling"), equestrianism ( -ria "again") or speaking ( -ku "towards"). Modifiers can also add actors that are not already given by the verb's subcategorization framework, e.g. B. causative -ware , which adds a new introductory or authorized agent and also the benefactive -iwa , which expresses a new benefactor.

| Directional demonstratives: | Adverbial-like modifiers: | Participant Modifier: | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Verb adjuncts

Irregular verbs can be connected with adjuncts that precede the root, but represent a kind of unit with the root, since the negation includes both elements. The connection between adjunct and root is not free, but almost fixed: certain adjuncts only work with special verbs. The verb nga "go" combines with the adjunct aru "be responsible for" to express the meaning "travel with, escort", and combined with the adjunct iri "fetch" it expresses "fetch to take away". This construction seems to be the result of previous verb serializations.

Flexion

| TAM markers | Regular shape |

|---|---|

| Perfective | - o ~ -u |

| Imperfect | - |

| Intentive | - nda |

| Desiderative | - no |

| tripod | - i |

| Habitual | - na |

| Prophetic | - na |

| Promissive | - white |

| Abilitative | - nopo |

| imperative | - pa |

| Prohibitive | - white |

| Hortative | - wae |

| warning | - wayeni |

| suggestion | HORT / INT + kone |

Inflection in Duna can be both mandatory and optional. Inflected elements are at the end of the verb's morphological structure. The obligatory flexion elements include Dunas TAM markers ( tense , aspect , modality ). Some evidential and information status markers encode the TAM contents alongside their own meaning and are used in place of the TAM markers. These are therefore also part of the mandatory inflection elements. Other markers of evidentiality and information status are optional and have scopus over verbs that have already been inflected, so they come after the TAM markers. They add perspective on how the proposition is valued. Epistemic modality markers are always optional and follow the mandatory inflection elements - they indicate subjective assessments.

Sentence structure

Basic structure of the sentence

The basic structure of the sentence is SOV . In ditransitive sentences, the object that represents the theme follows the object that marks the recipient .

| hina-ko | no | ki | nguani | ngua-na = nia. | |||

| this-CS | 1SG | k.pig | fat | give-HAB = ASSERT | |||

| subject | recipient | theme | V | ||||

| "This one would give me pig fat." | |||||||

There are two positions in the linearization for adjuncts . Following the assumption that adjuncts can be divided into two categories: those that are in some way part of the action denied by the verb, and those that rather describe the setting or the circumstances, the latter are related to the circumstance between subject and object and the former with Participants behind the objects. In structures with intransitive verbs, all adjuncts are behind the subject. Suffixes specify the type of adjunct, such as the instrumental marker -ka , which inherently indicates a participant reference, or the local marker -ta , which can be used for both participant-related adjuncts and circumstances, depending on whether the constituent is semantically part of the verb notation or complementary information.

| Participant reference + instrument: | Participant reference + local information: | Relation to circumstances + local information: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Non-verbal sentences

Identity or similarity of two elements can be shown without a copula by contrasting them. The same applies to adjectival predicates, in which subject and adjective are juxtaposed in order to express an assignment of properties.

| no | hinid | Paka. |

| 1SG | ground | PLN |

| "My homeland is Paka." | ||

| Yuna | haka | paya. |

| GPN | talk | good |

| "Duna language is good" | ||

Interrogative clauses

Questions are formulated in three ways in Duna. Interrogative pronouns can be in canonical position (same place as the answer). The interrogative marker -pe can also mark an interrogative sentence as a verbal suffix; this is optional for question words. As a third possibility, refrain questions can be used, where the speaker uses the interrogative marker and repeats the verb with the negation marker na- -ya .

Serialization

Related actions can be expressed by stringing together verb roots. Only the last root gets inflected endings, the properties of which are shared by all verbs. The verbs often have at least one argument that they share.

| Pambo | pi | kola | kuwa-rua. |

| cucumber | LNK | pick | carry-STAT.VIS.P |

| "[They] plucked and carried cucumbers." | |||

Remarks

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, the information is from San Roque (2008)

- ↑ With -ndu "one" there is no simple nominalization, because the connection results in the meaning "thing".

bibliography

- ^ San Roque, L .: An introduction to Duna grammar . Australian National University 2008 ( gov.au [PH.D]).

- ↑ Ross M .: Pronouns as a preliminary diagnostic for grouping Papuan languages . In: Pawley A., R. Atternborough, J. Golson, R. Hide (eds.): Papuan pasts: cultural, linguistic, and biological histories of Papuan-speaking peoples . Australian National University, Canberra: Pacific Linguistics 2005, pp. 15-65 .

- ↑ Pronouns as a preliminary diagnostic for grouping Papuan languages . In: Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, & Charles D. Fennig (Eds.): Ethnologue: Languages of the World (18th ed.) . SIL International, Dallas, Texas 2015, pp. 15-65 .

- ↑ Rebecca, R .: Big wet, big dry: the role of extreme periodic environmental stress in the development of the Kopiago agricultural system Southern Highlands Province, Papua New Guinea . Australian National University, Canberra: Pacific Linguistics 1999.

- ^ M. Donohue: Tone systems in New Guinea . In: Linguistic Typology . 1, 1997, pp. 347-386.

- ^ Andrews, AD: The major functions of the noun phrase . In: T. Shopen (Ed.): Language typology and syntactic description: Clause structure (= 1 ). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007, pp. 132-223 .

More reading

- Language and Cognition - Duna

- Aletta Biersack (Ed.): Papuan borderlands: Huli, Duna and Ipili perspectives on the Papua New Guinea Highlands . The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 1995.

- Duna New Testament. Ngodeya haga ayere ho. Prepared under the auspices of Christian Mission in Many Lands . Christian Books Melanesia Inc., Wewak 1976.

- Glenda Giles: A guide to the pronunciation of Duna . In: Manuscript held at SIL .

- K. Gillespie: Steep slopes: Song creativity, continuity and change for the Duna of Papua New Guinea . The Australian National University, 2007.

- G. Stürzenhofecker: Times enmeshed: Gender, space and history among the Duna of Papua New Guinea . Stanford University Press, Stanford, California 1998.