Fenestrelle fortress

Coordinates: 45 ° 1 '48.2 " N , 7 ° 3' 34.3" E

The Fenestrelle Fortress ( Italian Fortezza di Fenestrelle or Forte di Fenestrelle ) is the largest fortress in Europe and the next largest masonry after the Great Wall of China. It consists of the three fortresses of San Carlo , Tre Denti and Delle Valli , which are connected by a tunnel in which the longest covered staircase in Europe runs with almost 4,000 steps.

Overview and meaning

The fortification was built in the 18th and 19th centuries in the village of Fenestrelle in Val Chisone ( Province of Turin ). Because of its extension over the entire left side of the valley, it is also called the great wall of Piedmont . In 1999 it became the symbol of the province of Turin and in 2007 the World Monuments Fund included it in the list of the 100 most endangered cultural monuments (along with four other Italians). Originally intended by the engineer Ignazio Bertola to secure the Italian-French border, it was the scene of only minor skirmishes and a brief battle during World War II . It was then abandoned until 1990 and has since been restored, making it accessible to a wider audience (20,000 visitors in 2012).

The fortress consists of three forts, seven reduits , connected by glacis and bastions, stairs and risalits on a total area of 1,350,000 m 2 . The facility stretches over three kilometers and has an altitude difference of 635 meters. The fortress is also famous for its two long stairs: the inner Scala Coperta (roughly covered staircase ) with around 4000 steps, which allowed all parts of the complex to be reached safely, and the outer Scala Reale (roughly king staircase) with 2500 steps, which the king used on his visits.

It is the largest fortress dominating a valley head from the 18th century worldwide and the second largest military construction in terms of total length after the Great Wall of China. Together with the Forte di Exilles and the Forte di Vinadio , it forms one of the most significant defensive structures in Piedmont. The oldest part, the Forte delle Valli, is the last originally preserved from the 18th century in Italy, especially since the others have been demolished or modernized.

history

Until 1882

The history of the bastions on the territory of Fenestrelle began in 1690 when Louis XIV instructed General Nicolas de Catinat to lead his army in the campaign against the Duchy of Savoy during the Nine Years War . It soon became clear to General Catinat that the Chisonetal, and in particular the narrow valley near Fenestrelle, could pose a serious obstacle for the French army. Therefore he applied for the construction of three smaller fortresses and one large one. In 1692 the Sun King ordered the construction of the still small predecessor version of the later Fort Tre Denti . In 1694, again on the advice of Catinat, the King of France gave the order to begin building the impressive Fort Mutins in order to secure the border with the Duchy of Savoy. This fortress was completed in 1705 and played a role in the War of the Spanish Succession , in which the French and Savoy were at war. In the course of this conflict in August 1708 the troops of Viktor Amadeus II conquered Fort Mutin and the high valley after a fortnight siege .

The Treaty of Utrecht sealed this situation in 1713 by defining the border between France and the Duchy of Savoy (from which the Kingdom of Sardinia emerged in 1720 ) along the Alpine watershed Dora - Durance , whereby the Susa Valley and the Chisone Valley were awarded to Savoy.

Viktor Amadeus II considered Fort Mutin on the right side of the valley to be inadequate and therefore commissioned the architect and military engineer Ignazio Bertola to design an entire complex of fortifications, including Fort Mutin (which was restored after the Treaty of Utrecht) and other French fortifications for the Protection of the Turin plain from possible French invasion attempts through the Chisonetal. The corresponding plans were presented in October 1727 and construction work began in the summer of 1728 and ultimately lasted until 1850 with a long break between 1793 and 1836.

Ignazio Bertola was followed by various other military engineers and architects in the planning of the fortifications and the management of the construction work, among them: Vittorio Amedeo Varino de La Marche, Lorenzo Bernardino Pinto (a pupil of Bertola who also directed the construction work of Fort Exilles) , Nicolis Robilant and Carlo Andrea Rana. Victor Amadeus II , who was proclaimed King of Sardinia after the Kingdom of Sardinia was annexed to the Duchy of Savoy in 1720, saw only the partial realization of the fortifications during his reign, the construction of which he had ordered, since he was in favor of his son Karl Emanuel in 1730 III. abdicated , to whom he suggested the continuation of the construction work.

Bertola's original plan provided for an extension over the entire left side of the valley, but work began at the upper end, on Monte Pinaia , especially since the valley floor was protected by the restored Fort Mutin . The construction of the Reduits dell'Elmo , Sant'Antonio and Belvedere began , separated by moats and connected by bridges, forming the Forte delle Valli . As a result, there was a connection with the valley floor with the inclusion of an existing French redoubt, Forte Tre Denti through the construction of Forte San Carlo in 1731. The various parts of the complex were through the Strada dei Cannoni from Fenestrelle to Forte delle Valli and the Scala coperta with 3966 steps on the left side of the valley from the piazza d'armi des Forte San Carlo to the reduits des Forte delle Valli . To protect the valley floor from enemy attacks, the Reduit Carlo Alberto replaced the obsolete and collapsing Fort Mutin between 1836 and 1850 .

After the unification of Italy between 1874 and 1896, the fortress was upgraded and modernized for the last time. The reduits of Forte San Carlo were converted into casemates to accommodate the new rifled cannons 12 GRC / Ret and 15 GRC / Ret .

From 1882, when Italy joined the Triple Alliance , the areas of Fenestrelle and Assietta were militarily upgraded by further outposts, including Forte Serre Marie , Batteria del Gran Serin and behind the Colle delle Finestre , the fortino of the same name and the guardroom Falouel , which because of its cube-shaped Form il Dado (dice) was called.

From 1887

From 1887 until the end of World War I , the fortress was a garrison of the mountain battalion in the 3rd Mountain Regiment. A small museum with memorabilia of these soldiers can be visited with free entry inside the fortress. With the rise of fascism, the facility was once again used as a prison for political prisoners who were hostile to the regime or who did not collaborate. The spirit of that time can be seen from the inscription “Ognuno vale non in quanto è, ma in quanto produce” (for example “Everyone is not worth as much as he is, but how much he achieves” ), which is in one of the writing rooms found.

During the Second World War, the fortress experienced its only real military action when, in July 1944, the east side of the Carlo Alberto Redoubt was blown up by partisans from Adolfo Serafino's division in order to prevent the advance of German troops against the partisans in the Alpine valleys.

In 1946, after the end of the Second World War, the Italian army separated completely from the facility, which had become worthless from a military point of view. The fortress was abandoned, torn down by storms and looting. Over the years everything that could be carried was removed: windows and doors, even the barracks' ceiling beams. Since 1990 the facility has been repaired by a group of volunteers. Guided tours, theater and cultural events are offered. In 1992, the State Forests and the Ministry of Public Works started a general restoration project by the architect Donatella D'Angelo.

Three times jail

In addition to its military function, the fortress was three times a prison, first for common criminals, then a state prison and finally a penitentiary.

The ordinary prison

In a few cases common criminals from the area were housed. In special cases also from a larger area, under the same conditions, but under civil and non-military jurisdiction. The Campanian historian Giacinto de 'Sivo claimed that civilians from southern Italy were also detained in the fortress on the brigantry charges during the Napoleonic era .

The state prison

The state prison was used to detain convicted officers and members of the opposition - clergy and lay people. In the first years of the 19th century mainly Bourbon prelates, members of the opposition to Napoleon, including officers who followed Giuseppe Mazzini's ideas . In 1850, Monsignor Luigi Fransoni , Archbishop of Turin, was appointed for his oppositional role.

In individual cases, so-called dissolute minors were detained at the instigation of their parents who were guilty of crimes or who had disappointed their noble or wealthy parents. They underwent treatment similar to that in a cadet institution. Each prisoner had a private room, rarely several, with a fireplace and furniture. During the Napoleonic era, every prisoner had to live at his own expense, under the Savoy at the expense of the state.

During the fascist era, the fortress was also used as a place of exile.

The penitentiary

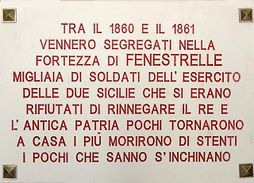

Translation of the inscription:

Between 1860 and 1861, thousands of soldiers of the army of the two Sicilies who refused to deny their king and their former fatherland were held in the fortress of Fenestrelle. Few returned home. Most died of starvation. The few who know this bow.

The penitentiary was also a military prison where, in addition to soldiers who had committed crimes or administrative offenses, soldiers from the armies whose states had been attacked by the Kingdom of Sardinia before the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy and afterwards, during the Risorgimento and the first decades of the 20th century in particular Austrians and Italians from the areas that stood under different sovereignty before the unification of Italy and who fought during the Italian Wars of Independence , members of the disbanded army of the two Sicilies who were captured during the wars for the integration of southern Italy, six followers of Garibaldi after his abortive attempt to Papal States to occupy, 462 soldiers of the army of the Papal States after the capture of Rome, Austro-Hungarian military personnel during the First world War . The inmates of the prison camp were locked in communal sleeping halls.

In the decade from 1860 to 1870 in particular, around 24,000 military personnel from the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies , who opposed the conquest and subsequent annexation of the two Sicilies into the newly formed Kingdom of Italy, were deported to the fortress. It was mainly Bourbon soldiers who were held captive, but also numerous farmers. The prisoners were held under the worst conditions: “ With ragged clothes and hardly anything to eat, they were often seen leaning against the walls, desperately trying to get something from the faint sunshine in winter, perhaps with nostalgic memories of the warmth in other Mediterranean climates. ““ No straw sacks, no blankets, no light, in places where the temperature was almost always below zero, windows and doors were taken out to re-educate those who had been secreted. "

The revolt

On August 22, 1861, the trapped tried to take control of the fortress through a revolt. The uprising was easily suppressed by the Piedmontese authorities. The result was a tightening of sentences (most of them were held with 16 kg bullets on their feet, shackles and chains). Very rarely were prisoners released by acquittal or pardon. The corpses of the dead were simply thrown into a large container behind the church (which rose at the entrance to the fortress): “ A death without honor, without graves, without tombstones and without remembrance, so that no traces of the atrocities would remain. "

Female prisoners

In the entire history of the fortress, only three women were held in the state prison: The Piedmontese Marchesa Polissena Gamba Turinetti di Priero and her daughter Clementina as opponents of Napoleon were held separately from the men in their own rooms in the officers' building. In 1864, Maria Oliverio, known as Ciccilla, was sentenced to life imprisonment for briganding, which she served 15 years until her death.

The fortress in detail

The Forte delle Valli

In 1728 the construction of the fortress began for reasons of accessibility and the strategic location at the summit of Monte Pinaia (1780 m) with the Forte delle Valli and the three associated Reduits dell'Elmo , Sant'Antonio and Belvedere . From there the fortifications below could be caught in the crossfire and the enemy prevented from enclosing them. The valley floor was already protected by Fort Mutin, which was rebuilt after the War of the Spanish Succession .

The three reduits were surrounded by deep trenches so that they could be held in the event of a siege, even if one had fallen. Because of the ditches, the reduits were connected with bridges: The Reduit Belvedere connected one fixed and two side drawbridges with the next Sant'Antonio. which was similarly associated with dell'Elmo . In addition, the Forte delle Valli was protected by thick openwork walls, massive trusses and bastions, which made it impregnable for the time.

It is connected to the road to Pra Catinat from the Reduit dell'Elmo , where today the Ponte Rosso is located, which bridges a large overhang with four arches. In the middle there is a huge iron grating between two high pillars with stone cannonballs on top. In addition, the Forte of the Reduit Belvedere is connected to the Strada dei Cannoni and the fortifications below and the village of Fenestrelle. The Reduit Belvedere , which is the first to be reached on the ascent from Forte Tre Denti , is the most extensive and best preserved of the Forte delle Valli and is the only one with a chapel for church services. It is connected to the other parts of the fortress not only through the Scala Coperta , but also through the Scala Reale . In the past, the only way to get from here to the fortress was via a drawbridge, which had been destroyed over time, through the Porta Reale (also known as Il Tempietto because of its decorative ornaments reminiscent of sacred buildings).

In view of its location in a mountain fortress, the now desecrated single-nave chapel must have been an impressive building. The baroque facade was adorned with pilaster strips and decorations made of yellow granite and the roof supported a small bell tower. Few decorative elements withstood the cold winds, winter frosts, and post-war looting; for example, the bell was stolen.

The fifty- step Scala delle Tre Traverse (so called because it was protected from bombing by three high walls), which begins in front of the connecting bridges to the Reduit Sant'Antonio , connects the Reduit with the Strada dei Cannoni . The latter as the smallest consists of only one building, which was partly carved out of the natural rock and contains a powder tower and three garrison rooms. There were two small-caliber mortars on its flat roof. The Reduit dell'Elmo is the last to be reached and gets its name from the fact that it protects the entire complex like a helmet. It is protected by a few massive barred windows and a small, completely vaulted door as the only entrance. On the west side it is dominated by seven casemates, which were installed after the middle of the 19th century as protection for the new cannons, six of which are against the road of the Colle delle Finestre , the highest one (1783 m), however, against the plateau of Pra Catinat were set up. To the north and east turned 10 upwardly open positions for light cannons against Pra Catinat and the lower Val Chisone.

Batteries and reduits between Forte delle Valli and Forte Tre Denti

There are two batteries and two reduits ( Santa Barbara and delle Porte ), which the latter were restructured and modernized after Italy entered the Triple Alliance in 1882.

The Battery dello Scoglio was armed with small artillery in three positions and also included a warehouse and a station for optical telegraphy .

On the mountain flank at 1550 m, the Reduit Santa Barbara is partially dug into the mountain as a square truncated pyramid with walls six meters thick. In the past, this reduit was connected to the outside of the wall by a drawbridge that allowed access to Strada dei Cannoni .

The Reduit delle Porte , similar to the Reduit Santa Barbara , but slightly larger with its own powder tower, is located at an altitude of 1680 m . Not far from it at 1708 m is the Battery dell'Ospedale , which was supposed to secure the Strada dei Cannoni and the military hospital outside the walls against the French border.

The Forte Tre Denti

The name of this fortification comes from three rock needles, the so-called denti (teeth). The French General Catinat had this oldest fortress built at an altitude of 1,400 m in 1692. After the Peace of Utrecht in 1731, it was rebuilt and expanded by the Savoy family by Antonio Bertola ( Ignazio's adoptive father ). A lookout, the so-called Garitta del Diavolo, on a rock spur with an overhang of over 20 meters can only be reached via a narrow rock staircase. The Forte Tre Denti was equipped with six long range cannons, a kitchen, storage rooms, a cistern and a powder tower. A 424 meter long aqueduct supplied it and the Forte San Carlo below with spring water.

The Risalite

There are 28 risalits (artillery positions), visible from afar and of impressive appearance, whose majesty so impressed the writer De Amicis that he reported about them in his book Alle Porte d'Italia . The risalites are connected to each other by protected stairs, numbered from bottom to top, they wind their way up the mountainside from Forte San Carlo to Forte Tre Denti with three bastions: San Carlo , Beato Amedeo and Sant'Ignazio . The first 16 are protected by a wide and deep moat that continues down to the Reduit Carlo Alberto . The artillery was stationed inside the risalits: cannons, mortars and finally machine guns . 22 of the 28 risalits are open at the top and surrounded by four walls, the other 6 were provided with casemates in the 19th century, artillery positions - opened at the back to allow the muzzle gases to escape.

The Fort San Carlo

Built between 1731 and 1789, it is the most important, best preserved and most representative section of the complex. Here high officers, ambassadors and nobles were received at the Porta Reale (the king's gate). Inside are the governor's palace, the officers' building, the garrison quarters, a church, a large powder tower, stores, laboratories and a pharmacy. The Scala Coperta also begins here . The 44-room governor's palace, built of stone and brick, was begun in 1740 and extends over four floors, one of which is below ground level with walls over two meters thick. The facade is well preserved and decorated with cornices . and decorated bars . Here was the kitchen for the governor and high officers. From 1780 to 1789, the Padiglione degli Ufficiali, sober except for the Baroque-style portal , was built on the Piazza d'Armi as accommodation for officers and as a detention center for high-ranking people and officers who have committed administrative offenses. The kitchen, pantry and water basin, which were fed by the cistern, as well as ovens were located underground.

The church of Forte San Carlo is the largest sacred building in a mountain fortress in Europe. The time of construction and the architect are unknown. It later served as a magazine. Today, after the restoration (especially of the roof and floor), the church serves as a venue for exhibitions, concerts and theater performances.

Another important part of the complex were the quarters for housing the soldiers, the largest of which were in San Carlo. They were three three-story buildings standing parallel to each other on the slope that extends to the higher fortifications. Originally planned as barracks with large rooms, they were later used as military cells and prison. The roof was covered with two layers of slate, while the inside showed a barrel vault. The upper floors were made of larch wood, but this was removed during the years of neglect. The most important powder tower in the whole fortress is the Polveriera Sant'Ignazio, named in honor of Ignazio Bertola, above the quarters of a square plan with triple walls of remarkable thickness.

The two stairs

The Scala Coperta begins in the Piazza d'Armi des Forte San Carlo , from where arcades lead to the tunnel. It is unique in Europe with 3996 steps. Over a length of around 2 km with an altitude difference of 530 meters, it connects the entire fortress from Forte San Carlo to Forte delle Valli, also to ensure unimpeded access to all parts of the complex in the harsh alpine winters. Originally designed for mules, the steps are uncomfortable for people and were therefore considered spacca gambe ( leg breakers, for example ). For a number of years flights of stairs have been organized.

Another important staircase flanks the Scala Coperta at the height of Forte Tre Denti. It is the Scala Reale , which is also suitable for climbing with mules, but outdoors it consists of only 2500 steps. It was used for communication between the batteries and reduits between Forte Tre Denti and Forte delle Valli and when the king visited - hence the name.

More buildings

Fort Mutin

Fort Mutin was built at the instigation of Louis XIV from 1694 to defend the valley floor against Savoy troops from the direction of Pinerolo . The five-sided structure with an area of around 96,000 m 2 was built according to plans by Guy Creuzet de Richerand, who was responsible for fortifying the Dauphiné at the time . As the siege by troops of the Duchy of Savoy in 1708 showed, the fort's location is unfavorable: it is located in a hollow that is exposed to enemy attacks, which the famous architect and general commissioner of French fortifications, Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, vehemently did during his visit in 1700 criticized. He would have preferred a demolition, because of the political situation and the costs he had eight reduits built to protect the fort on both sides of the valley instead. Nevertheless, such efforts were of no avail when on August 31, 1708, after a siege of 15 days, Fort Mutin surrendered to Piedmontese troops after the bombing of its powder tower.

At the instigation of Viktor Amadeus II , the fort was restored, with the guns now directed against France. It remained in use until 1836 when it was partially demolished as a result of the construction of the Carlo Alberto Redoubt .

Of this construction from the late 17th century, only the ruins of the fortress remained.

The Reduit Carlo Alberto

In 1836 the military council decided to demolish Fort Mutin , which - now obsolete - was replaced by a new structure that secures the lowest point in the valley. The new fortress was named after the current King Karl Albert , who financed it. The reduit originally consisted of two squat adjoining buildings on the left bank of the Chisone above today's Strada Provinciale 23 del Colle di Sestriere . The remaining building is a square truncated pyramid with five floors, two of which are below street level. The other four-story building was blown up in July 1944 by partisans from A. Serafino's division in order to hinder German clean-ups and the advance into the upper valley. Due to its location on the street, it controlled this traffic route with two drawbridges and two drop gates. The Reduit Carlo Alberto was connected to the fortress by a moat that reached the western clasp of Forte San Carlo . The pigeon house could also be reached through a protected path. What remained of the Reduit Carlo Alberto is now in private ownership, which it came into immediately after the end of the Second World War.

The pigeon house

Before the establishment of optical signal transmission , the use of carrier pigeons was essential. The pigeon house was used to raise and house the carrier pigeons. The chateau Arnaud from the 13th century was adapted for this purpose, a squat square building that was one of the bailiff's seats until the annexation of Fenestrelle by France in 1349 and then gradually became the representative seat of the Dauphin in the upper Val Chisone . After the Second World War, the pigeon house was handed over to private individuals and is therefore almost intact.

literature

- Mario Reviglio: La Valle contesa. Editrice Il Punto, Torino 2006.

- Dario Gariglio: Le Fenestrelle. Roberto Chiaramonte editore, Torino 1999.

- Dario Gariglio, Mauro Minola: Fenestrelle e l'Assietta. In: Le fortezze delle Alpi Occidentali. Volume 1: Dal Piccolo S. Bernardo al Monginevro. Edizioni L'Arciere, Cuneo 1994, ISBN 88-86398-07-7 , pp. 97-126.

- Alberto Bonnardel, Juri Bossuto, Bruno Usseglio: Il Gigante Armato. Fenestrelle fortezza d'Europa. Editrice Il Punto, Torino 1999, ISBN 88-86425-66-X .

- Juri Bossuto, Luca Costanzo: Le catene dei Savoia. Cronache di carcere, politici e soldati borbonici a Fenestrelle, forzati, oziosi e donne di malaffare. Editrice Il Punto, 2012.

- Alessandro Barbero : I prigionieri dei Savoia. Editori Laterza, Roma-Bari 2012.

- Mauro Minola: Fortezze del Piemonte e Valle d'Aosta. 2nd Edition. Susalibri, 2012, ISBN 978-88-88916-69-9 , pp. 127-136.

- Forte di Fenestrelle, la Grande Muraglia Piemontese. Editrice Il Punto, Torino 2009.

- Rocco Giuseppe Greco: L'ultima brigantessa. Marcovalerio, Torino 2008.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Very close to the Via Alpina path: the Forte di Fenestrelle

- ↑ a b Homepage of the Province of Turin

- ↑ archiviostorico.corriere.it

- ↑ ocp.piemonte.it

- ↑ altavalchisone.it

- ↑ a b Homepage of the fortress

- ↑ a b c d e The Fortress of Fenestrelle in detail ( Memento of the original from April 20, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ scribd.com The Fortress of Fenestrelle. A Historical Introduction and Synthesis of Restoration

- ↑ a b c d e Riccardo Chiarle: La fortezza di Fenestrelle. 2006, pp. 36-40.

- ↑ a b Mauro Minola: Fortezze del Piemonte e Valle d'Aosta. Susalibri, p. 127.

- ^ Forte di Fenestrelle, la Grande Muraglia Piemontese. Il Punto, Turin 2009, ISBN 978-88-86425-93-3 , pp. 33-34, 61.

- ↑ Mauro Minola: Fortezze del Piemonte e Valle d'Aosta. 2nd Edition. Susalibri, 2012, p. 128.

- ^ Forte di Fenestrelle, la Grande Muraglia Piemontese. Il Punto, Turin 2009, ISBN 978-88-86425-93-3 , p. 22.

- ↑ Giacinto de 'Sivo; Storia delle Due Sicilie, dal 1847 al 1861; online ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Rome 1863, p. 46.

- ↑ a b c d e Il Forte di Fenestrelle, la Grande Muraglia Piemontese. Il Punto, Turin 2009, ISBN 978-88-86425-93-3 , pp. 49-53.

- ↑ a b c d Alberto Bonnardel, Juri Bossuto, Bruno Usseglio: Il Gigante Armato. Fenestrelle fortezza d'Europa. Il Punto, Turin 1999, ISBN 88-86425-66-X , pp. 121-126.

- ↑ a b c d Le Fortezze delle Alpi Occidentali; Dario Gariglio and Mauro Minola. Edizioni L'Arciere, Cuneo 1994, ISBN 88-86398-07-7 , pp. 97-126.

- ↑ a b c piemontemese.it ( Memento of the original from April 20, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Alberto Bonnardel, Yuri Bossuto, Bruno Usseglio: Il Gigante Armato. Fenestrelle fortezza d'Europa. Il Punto, Turin 1999, ISBN 88-86425-66-X .

- ^ A b Alberto Bonnardel, Juri Bossuto, Bruno Usseglio: Il Gigante Armato. Fenestrelle fortezza d'Europa. Il Punto, Turin 1999, ISBN 88-86425-66-X , pp. 118-120.

- ^ A b Il Forte di Fenestrelle, la Grande Muraglia Piemontese. Turin 2009, ISBN 978-88-86425-93-3 , pp. 45-49.

- ↑ a b piemontemese.it

- ↑ a b c Il Forte di Fenestrelle ( Memento of the original from April 20, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ A b Alberto Bonnardel, Juri Bossuto, Bruno Usseglio: Il Gigante Armato. Fenestrelle fortezza d'Europa. Torino 1999, ISBN 88-86425-66-X .

- ↑ La Fortezza di Fenestrelle. Composizione

- ↑ La Fortezza di Fenestrelle. Composizione

- ↑ fortedifenestrelle.com ( Memento of the original from May 3, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c d fortedifenestrelle.it ( Memento of the original from April 13, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ news.sportduepuntozero.it ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Domenica la Corri-Forte a Fenestrelle; June 28, 2013.

- ↑ La Fortezza di Fenestrelle. Composizione

- ↑ a b c Mauro Minola: Fortezze del Piemonte e Valle d'Aosta. Susalibri, 2012.

- ↑ a b comune.fenestrelle.to.it

- ↑ The Fortress of Fenestrelle: Historical Background ( Memento of the original from May 1, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Homepage of the Fortezza di Fenestrelle: La Ridotta Carlo Alberto ( Memento of the original from November 1, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.