Fritz Rotter (theater entrepreneur)

Fritz Rotter (born September 3, 1888 as Fritz Schaie in Leipzig ; † October 7, 1939 in Colmar ) was a German theater operator (the so-called Rotter theaters), director and producer.

The early successes

The brothers Fritz and Alfred Rotter were considered the busiest theater makers in Berlin during the Weimar Republic : two colorful personalities, their uncontrolled theatrical accumulations, interlaced company structures and daring financing concepts shortly before Adolf Hitler came to power, leading to a much noticed and widely publicized scandal in the late phase of the first German Democracy should lead.

At Alfred's side, Fritz Schaie acquired the basics of making theater at the Deutsches Schauspielhaus , in the establishment of which both fathers once had a financial share. In the middle of the war, the Schaie brothers, who had renamed themselves to Rotter at an early stage, acquired their first own venue, the Trianon Theater . Soon after, the next Berlin venue followed with the Residenz Theater . Most recently, they operated a total of nine houses, some as directors, but mostly as tenants. The Rotterdam stages included u. a. the Metropol-Theater , the Theater des Westens , the Lessingtheater , the Lustspielhaus and the Centraltheater , in which classics (plays by Euripides , Sophocles , Shakespeare , Lessing ) as well as plays by modern authors (including Ibsen , Hauptmann and Shaw ) were performed. The Rotter brothers achieved their greatest commercial successes primarily at the Metropol Theater, the venue for the light muse. There they performed lively revues and operettas as well as numerous tabloid pieces, some of them in their own production.

One of the greatest successes of the Rotter brothers was the world premiere of Paul Abraham's operetta Ball in the Savoy in the Großes Schauspielhaus on December 23, 1932 with Gitta Alpár and Oskar Dénes , which the NSDAP forced to dismiss in connection with the boycott of Jews in early April 1933. Numerous Berlin theater and film greats were supported by the Rotters and earned extra income on their stages.

The collapse of the Rotter Group

In the late phase of the Weimar Republic, the nested Rotter Group - six GmbHs and two stock corporations - got more and more into serious financial difficulties (around four million RM bank and mortgage debts), as even the Rotter brothers lost their way in the course of the uncontrolled accumulation of arcades Threatened to lose track. Alfred and Fritz Rotter had often chosen constructions for their companies that freed them from any responsibility in the legal sense in the event of a crisis. Numerous financial claims from creditors went unheard - rent arrears, for example, which led the owner of the Metropol Theater, the Dorotheenstadt-Baugesellschaft, to file for bankruptcy against the Rotters on January 17, 1933.

In 41 lawsuits, the Association of German Stage Writers and Stage Composers alone tried to force the Rotters to finally pay their royalty debts. In addition, some late Rotter productions (around 1932) turned out to be huge box office flops. No two weeks before the coming to power of the Nazis , on 18 January 1933, the reported Vossische newspaper for bankruptcy against the Rotter brothers. The Berliner Börsen-Zeitung even spoke of the collapse of the Rotterdam stages on the same day . Over 1300 employees of the collapsing corporate conglomerate lost their jobs from one day to the next.

Now de facto bankrupt, sat Alfred and Fritz Rotter, apparently following the Kurfürstendamm riot of 1931 had adopted in October 1931 for safety the citizenship of the Principality of Liechtenstein, on 9 or 22 January 1933, first in the Switzerland , then to Vaduz ( Liechtenstein ). Fritz Rotter in particular had desperately tried to find fresh capital to avert the complete collapse of the corporate empire. On January 22, 1933, the Mitte district court issued an arrest warrant for the brothers.

"Rotter Abduction"

The National Socialists, who came to power on January 30, 1933, used the dazzling financial scandal surrounding the Jewish brothers for hateful, anti-Semitic propaganda campaigns in images and sound. In direct connection with the boycott of Jews that the NSDAP had carried out in the German Reich the previous week, there was an attempt to kidnap both Rotters from a Liechtenstein forest hotel to Germany on April 5, 1933 , but this failed. Alfred Rotter and his wife Gertrud were killed in a hunt through the mountains, while Fritz Rotter escaped the persecutors - German and Liechtenstein Nazi supporters - injured.

Emigration and persecution

Fritz Rotter's following years of life are only incompletely documented. After a lengthy stay in hospital, he was able to escape to France via Switzerland in mid-May 1933 with the support of the Zurich lawyer Wladimir Rosenbaum ; He had to leave his Berlin luggage behind in Vaduz. In both countries, however, he was also not safe from stalking by National Socialist authorities. In France, under German pressure, he was arrested by the local police in November 1934. As the German-language exile newspaper Pariser Tageblatt reported in its February 3, 1935 edition, Rotter was released from his custody in Aix-en-Provence in February 1935 at the behest of the French government . At that time, in view of an intervention by the Liechtenstein tax administration, he no longer had any valid Liechtenstein papers that would have been indispensable for a further trip overseas.

Another emigrant publication , Pem's-Privat -berichte , reported in the August 3, 1937 edition that Rotter had been arrested again in Switzerland on the basis of an old request for extradition from the German Reich . Apparently this request was not complied with. In December of the same year, Pem's published a report according to which Rotter was in great (financial) need in Paris . On June 22nd, 1938, it was said that Rotter's plan to get Albert Bassermann off the ground had failed.

The last message from him came from the last few weeks before the start of World War II . Pem's Privat reports from July 25, 1939 reported that Rotter had been arrested for bad checks in the casino in the French city of Boulogne . For decades it was unknown whether Fritz Rotter was imprisoned again as an 'enemy foreigner' after the outbreak of war and later deported after the Wehrmacht invaded France, or whether he managed to escape to a safe country abroad. As was only made public about 80 years later by his biographer Peter Kamber, Fritz Rotter was killed for unknown reasons in October 1939 while serving a six-month prison sentence in Colmar in Alsace . The French authorities had already issued an arrest warrant against Rotter in connection with bad checks in the autumn of 1938. Rotter was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Colmar.

The turmoil around the beginning of the Second World War caused by Germany's military attack on Poland and the resulting declaration of war by France and Great Britain on the German Reich in the previous weeks may have contributed to the fact that Rotter's death was not publicly known at the time.

Web links

literature

- Kay Less : Between the stage and the barracks. Lexicon of persecuted theater, film and music artists from 1933 to 1945 . With a foreword by Paul Spiegel . Metropol, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938690-10-9 , p. 298 (entry by Alfred Rotter).

- Peter Kamber: Fritz and Alfred Rotter. A life between theatrical splendor and death in exile . Henschel Verlag in EA Seemann Henschel, Leipzig 2020, ISBN 978-3-89487-812-2 .

- Peter Kamber: The collapse of Alfred and Fritz Rotter's theater company in January 1933. The reports of the Berlin bankruptcy and the anti-rot sentiment in the trial of their kidnappers . In: Yearbook of the historical association for the Principality of Liechtenstein, Volume 103, 2004 ( digitized version )

- Peter Kamber: On the collapse of the Rotter theater company and on the further fate of Fritz Rotter. New research results . In: Yearbook of the historical association for the Principality of Liechtenstein, Volume 106, 2007 ( digitized version )

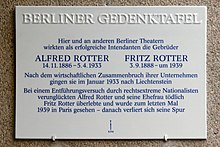

- Peter Kamber: Short address on the inauguration of the memorial plaque for Fritz and Alfred Rotter . Berlin, Theater im Admiralspalast, July 4th, 2008 ( PDF )

- Rotter, Fritz , in: Frithjof Trapp , Bärbel Schrader, Dieter Wenk, Ingrid Maaß: Handbook of the German-speaking Exile Theater 1933 - 1945. Volume 2. Biographical Lexicon of Theater Artists . Munich: Saur, 1999, ISBN 3-598-11375-7 , p. 808

Individual evidence

- ^ Peter Kamber: Fritz and Alfred Rotter. A life between theatrical splendor and death in exile . Henschel Verlag in EA Seemann Henschel, Leipzig 2020, p. 459 f.

- ^ Peter Kamber: Fritz and Alfred Rotter . Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2020, p. 18.

- ^ Peter Kamber: Fritz and Alfred Rotter . Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2020, pp. 229–238, 259.

- ^ Peter Kamber: Fritz and Alfred Rotter . Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2020, p. 193.

- ^ Peter Kamber: Fritz and Alfred Rotter . Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2020, pp. 307–327.

- ^ Peter Kamber: Fritz and Alfred Rotter . Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2020, pp. 347, 390-420.

- ^ Peter Kamber: Fritz and Alfred Rotter . Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2020, pp. 423-426.

- ↑ http://deposit.dnb.de/cgi-bin/exilframe.pl?ansicht=3&zeitung=paritagb&jahrgang=03&ausgabe=418&seite=17870001

- ^ Peter Kamber: Fritz and Alfred Rotter . Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2020, p. 455.

- ↑ http://deposit.dnb.de/cgi-bin/exilframe.pl?ansicht=3&zeitung=pemsbull&jahrgang=1937&ausgabe=66&seite=01300035

- ↑ http://deposit.dnb.de/cgi-bin/exilframe.pl?ansicht=3&zeitung=pemsbull&jahrgang=1937&ausgabe=86&seite=01710076

- ↑ http://deposit.dnb.de/cgi-bin/exilframe.pl?ansicht=3&zeitung=pemsbull&jahrgang=1938&ausgabe=112&seite=02230032

- ↑ http://deposit.dnb.de/cgi-bin/exilframe.pl?ansicht=3&zeitung=pemsbull&jahrgang=1939&ausgabe=169&seite=03360050

- ^ Peter Kamber: Fritz and Alfred Rotter . Henschel Verlag, Leipzig 2020, p. 459 f.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rotter, Fritz |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Schaie, Fritz (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German theater operator |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 3, 1888 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Leipzig |

| DATE OF DEATH | 20th century |