History of Ireland (1801-1922)

This article covers the history of Ireland from 1801 to 1922 .

Act of Union and Catholic Emancipation

Ireland was still in the aftermath of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 in the early 19th century . Prisoners were still being deported to Australia and isolated outbreaks of violence continued (particularly in County Wicklow ). In 1803 there was another unsuccessful rebellion led by Robert Emmet . In 1801, the Act of Union united Ireland and the Kingdom of Great Britain by law to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland . This was an attempt by the British Crown to prevent Ireland from acting as a base for an invasion of Britain.

During this time Ireland was ruled by British authorities. These were the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland , who was installed by the King, and the Chief Secretary for Ireland , who was appointed by the British Prime Minister. During the 19th century, the British Parliament took over both the executive and legislative branches of government from the monarch. Because of this, the Chief Secretary became more important than the Lord Lieutenant, who played a more symbolic or representative role. Following the abolition of the Irish Parliament, Irish Members of Parliament were directly elected to the British Parliament in the Palace of Westminster . The British administration in Ireland - euphemistically referred to as " Dublin Castle " - remained dominated by Protestants until 1922 .

Part of the acceptance of the Act of Union among Irish Catholics was the prospect of abolishing the remaining penal laws and creating Catholic emancipation . But King George III. stopped emancipation on the grounds that it would break his oath of office to protect the Anglican Church. Only a campaign under the lawyer and politician Daniel O'Connell and his Catholic Association ( Catholic Association ) founded in 1823 finally led to emancipation in 1829, which allowed Catholics to be elected to parliament. In contrast, O'Connell failed (at that time head of the Repeal Association - withdrawal movement ) with its struggle for the abolition ( repeal ) of the Act of Union and the restoration of the independent Irish government. O'Connell fought these struggles almost non-violently and used public gatherings to demonstrate support.

Despite O'Connell's peaceful methods, there was some violence and resentment among the population in the first half of the 19th century. Violence against people of different faiths repeatedly broke out in the province of Ulster . B. in the so-called Battle of Dollys Brae on July 12, 1849, when at least 30 Catholics were killed during a march of the Orange Order . The inequalities between the rapidly growing rural poor population on the one hand and their landlords and the state on the other led to social tensions. Secret (mostly rural) organizations like the Whiteboys or the Ribbonmen used sabotage and violence to force the landlords to treat their tenants better. Perhaps the most sustained outbreak of violence was the Tithe War in the 1830s, when Irish Catholics refused to pay the mandatory tithe to the Anglican clergy. In response to this violence, the Irish Constabulary was formed, a police unit for the rural areas.

Economic problems

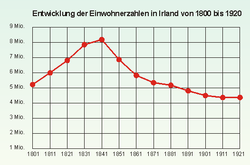

Ireland experienced various extreme economic ups and downs in the 19th century; from the economic boom during the Napoleonic Wars to the great famine in the second half of the century, during which around a million people died and another million emigrated.

Ireland's economic problems were largely due to the structure of land ownership: the lands belonged to a few landlords , while the majority of the population lived in poverty as tenants and had few rights vis-à-vis their landowners. Population growth and the division of inheritance led to the ever increasing fragmentation of the leased land. In addition, the estates from which the farmers leased their land were often poorly run by non-Irish absentee landlords and had heavy mortgages. Other factors were the almost complete lack of transport infrastructure (in the years before the famine there were no canals in Ireland and just 10 km of railroad tracks around Dublin) and the widespread lack of employment opportunities outside of agriculture.

The great famine

When the potato rot ravaged the island in 1845 and in the following years , the poor and with it the majority of the population in Ireland lost their staple food. The British government - first under Prime Minister Robert Peel , later under Lord John Russell - then acted strictly according to the laissez-faire principles, according to which any interference by the state in the economy and thus in the food trade was prohibited; nevertheless the landowners continued to export the agricultural produce to England during these years. Public aid programs in Ireland were in place but proved insufficient and the situation spiraled out of control when epidemics of typhoid , cholera and dysentery emerged. Aid money and supplies from around the world also failed to save what had sparked the British government's inaction - the farm worker class was nearly wiped out.

A small republican organization called the Young Irelanders attempted to start a rebellion against British rule in 1848. The result was only a small argument (mockingly the " battle of widow McCormack's cabbage patch " called the "battle of widow McCormack's cabbage patch ") with the police, which was quickly brought under control.

The famine at that time drove the first wave of emigrants to the United States , England , Scotland , Canada and Australia . With the ongoing political tension between the United States and Britain, the large and influential Irish-American diaspora funded and encouraged the Irish independence movement. In 1858 the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB - also known as the Fenians ) was founded, a secret society devoted to the armed struggle against the British. A similarly aligned group in New York called Clan na Gael organized various robberies in British Canada. Although the Fenians were very present in the rural areas, the Fenian uprising in 1867 proved to be a fiasco and was quickly nipped in the bud by the police. Because of the harsh anti-sedition and sedition laws, support for the republican movement was at a low point; until the 1860s, gatherings of Irish nationalists ended with the singing of "God Save the Queen" and royal visits to Ireland were accompanied by cheering crowds.

Country War

After the famine, hundreds of thousands of Irish farmers and workers had left or perished. Those who were left gradually began to fight for more rights and redistribution of the land. This period of Irish history is also known in Ireland as the Land War ("war for land") and involved both nationalist and social goals. The reason for this was that since the Plantations in the 17th century the class of landowners in Ireland consisted almost entirely of Protestant settlers with English roots. The Irish (Roman Catholic) population was largely of the opinion that the land had been unjustifiably expropriated from their ancestors. The Irish Land League was established to represent the interests of farmers. The first demand was the "three F's": fair lease, free sale and fixed rent. When the potential for mass mobilization was recognized, nationalist leaders like Charles Stewart Parnell became active in these movements.

Probably the most effective “weapon” of the Land League was the boycott (the word has its origin here): Unpopular landlords were ostracized by the local community. The Land League base also used violence against the landlords and their property - attempted evictions of tenants regularly ended in armed conflicts. British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli put Ireland under a kind of martial law to curb violence. Parnell, Michael Davitt and other Land League leaders have been temporarily detained for being seen as instigators of violence.

Ultimately, the "land issue" was resolved by gradual Irish Land Acts introduced by the British government, beginning with the William Gladstone Act in 1870 , which gave farmers the first extended rights. It was Gladstone who set up the Irish Land Commission , which bought land from the landlords and gave it to the peasants. This led to the emergence of a large new class of small landowners in the country and divided the power of the old Anglo-Irish landowners. But this did not help end support for Irish nationalism, as the British government had hoped.

Home Rule Movement

Until the 1870s, the Irish elected liberal and conservative politicians from British parties as their representatives in the British Parliament in Westminster . Irish Unionists only voted for a small minority. In 1873, Isaac Butt, former conservative lawyer and member of the Orange Order and now nationalist fighter, founded the moderate nationalist Home Rule League movement . After his death in 1879, William Shaw became the new leader and, together with the young Protestant landowner Charles Stewart Parnell , who led the Nationalist Party , transformed the Home Rule movement into an influential political one by transforming it into the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) Force. The party's growing popularity was evident as early as 1880 when the Home Rule League won 63 seats (2.8%). In the election in 1885, the party already won 86 seats (6.9%) - one of them in the English city of Liverpool, which is inhabited by many Irish . The party was able to hold this number of seats until the 1910s.

Parnell's movement fought for the right to self-determination and the possibility of an independent Irish government within the UK . This was in contrast to Daniel O'Connell , who called for the Act of Union to be withdrawn entirely . Two Home Rule bills (1886 and 1893) were tabled under Liberal Prime Minister William Gladstone , but neither was enforced.

The island was divided on the Home Rule issue: A national minority of Unionists (mostly, but not exclusively from Ulster ) opposed Home Rule , fearing that an Irish parliament in Dublin dominated by Catholics and nationalists would discriminate against them.

In 1892, a year after Parnell's death, his divorce scandal spread the movement and the whole country when it was learned that Parnell had had an affair with the wife of a party member for years. Although the party was never split, internally it was split into two camps (pro and anti-Parnell) , each of which ran with its own candidates until 1899, when they were reunited under John Redmond .

In 1912, at the height of the IPP, a third Home Rule Bill was introduced, which was approved in the British House of Commons, but rejected in the House of Lords (like the bill from 1893). But in contrast to the second Home Rule Bill , the House of Lords no longer had the power to block a legislative proposal approved by the House of Commons, but only the option of delaying it (up to two years). During those two years Ireland was on the brink of civil war as the fronts between proponents and opponents of the Home Rule intensified. Armed groups like the Ulster Volunteer Force or the Irish Volunteers were formed and also showcased their strength (and armament) through public parades.

Although nationalism dominated Irish politics at the beginning of the 20th century, various social and economic problems resulted in new trouble spots. Dublin was on the one hand glorious and wealthy, but on the other hand it also had the worst slums in the British Empire. Dublin also had one of the world's largest red light districts, named Monto after the central point, Montgomery Street (now Foley Street) in the northern part of the city.

Unemployment in Ireland was high and wages and working conditions were often very poor. To counter this grievance, the first unions at association level emerged among socialist activists such as James Larkin or James Connolly . In Belfast in 1907, under Larkin, bitter strikes by 10,000 dock workers took place. Dublin saw an even bigger strike in 1913 when 20,000 workers were fired or went on strike during the Dublin Lockout for being members of Larkin's ITGWU (Irish Transports and General Workers Union). Three people died during the riot and many more were injured. During the lockout, Larkin formed the Irish Citizen Army (which also took part in the 1916 Easter Rising ) to protect the striking workers from the Dublin Metropolitan Police as well as from scabs .

In May 1914, the Home Rule could no longer be prevented by the British House of Lords, but enforcement was postponed due to the outbreak of the First World War - initially to 1915, as it was assumed that the war would be brief. Many of the members of the Ulster Volunteer Force and Irish Volunteers joined the British Army during the war, fighting for example in the 36th (Ulster) Division, the 10th (Irish) Division or the 16th (Irish) Division. They fought mainly on the Western Front, Gallipoli and in the Middle East . It is believed that 30,000 to 50,000 Irish perished during the war. Both groups assumed that the British government would agree to the request of the respective group after the war if its members showed themselves loyal to the war.

Before the end of the World War, Britain made two attempts to introduce the deferred Home Rule Bill (one in May 1916, the other 1917–1918), but the Irish nationalists and unionists could not count on Ulster to be banned temporarily or permanently from the bill some.

The Easter Rising and the Consequences

Before that, the combination of the postponed Home Rule Bill and England's participation in a major war ("England's difficulties are Ireland's opportunities" - a statement by the Republicans) ensured that radical nationalist groups saw their chance in physical violence. A considerable part of the Irish Volunteers were extremely dissatisfied with the service of the Irish nationalists in the British Army and an armed uprising was planned from among their ranks together with the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1916 .

Due to internal disputes among the leaders of the volunteers, however, only a small part (around 1500) could be mobilized for the rebellion that began on Easter 1916 under Patrick Pearse and James Connolly . At the beginning of the uprising, an independent Irish Republic was proclaimed outside the Central Post Office (GPO) in Dublin. After almost a week of bitter struggle, the rebellion was finally put down. The victims of the uprising are difficult to gauge. It is believed that around 500 British soldiers lost their lives. The Irish (including civilians) were likely to have twice as many casualties. The material damage within the largely destroyed city was put at 2,500,000 pounds.

During the uprising, civilian support for the rebels was rather low, but this changed after the rebellion when the British government had the rebel leaders (including Patrick Pearse and Thomas J. Clarke ) executed without any real judgments . Eamon de Valera , who was also involved in the uprising, only luck and his American origins saved life. These mass executions led to a sharp rise in sympathy for the rebels and nationalist aspirations.

The government and the Irish media first (wrongly) accused Sinn Féin of initiating the rebellion, then a small monarchist party with only a small base. Eamon de Valera and other high-ranking survivors of the rebellion, however, joined Sinn Féin in large numbers after their return from prison, radicalized the program and assumed leadership.

Until 1917, Sinn Féin fought under its founder Arthur Griffith for an independent Ireland, albeit in the form of a dual monarchy under a common monarch with Great Britain. The dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary served as a model . In contrast, there were the efforts of (inter alia) de Valera, who sought a completely independent Irish republic. Internally, the party divided this question into two camps.

At the party meeting ( Ard Fheis ) in 1917, both camps finally reached a compromise: They decided to fight for their own republic and, if this goal was achieved, wanted to call a referendum that would decide between republic and monarchy. In the event of a decision in favor of the monarchy, however, the ruler should not have become a member of the British royal family.

From 1917 to 1918, Sinn Féin and the Irish Parliamentary Party fought a very bitter election campaign - each of the two parties won and lost individual by-elections. Sinn Féin eventually gained an advantage when the British government tried to introduce conscription in Ireland in order to secure supplies for their World War II deployment. This turned the Irish population against Great Britain and finally led to the so-called conscription crisis (Ireland) ( Conscription Crisis ).

In the 1918 election , Sinn Féin won 73 out of 105 seats - many of them unopposed. The newly elected MPs from Sinn Féin refused to take their seats in the British Parliament (as Members of Parliament - MP) in Westminster and instead gathered as the First Dáil - a revolutionary Irish parliament - in the Mansion House in Dublin. They proclaimed an Irish Republic and tried to build a functioning system of government.

The War of Independence 1919–1921

From 1919 to 1921 the Irish Republican Army (IRA) fought a guerrilla war against the British Army and paramilitary police units such as the Black and Tans or the Auxiliary Division . Both sides committed various atrocities during this war; the Black and Tans deliberately burned entire villages and tortured civilians; the IRA killed civilians believed to have passed on information to the British and (in retaliation) burned down various historic homes belonging to British supporters.

In the background, the British government tried to enforce self-government in Ireland by means of the postponed Home Rule Bill of 1914. The British cabinet created a new committee (the Long Committee ) to deal with the implementation of the Bill. It was, however, very unionist as the members of the First Dáil who boycotted Westminster were not involved. The deliberations eventually resulted in a fourth Home Rule Bill - also known as the Government of Ireland Act . However, the Act favored the interests of the Ulster Unionists and now finally divided Ireland into two areas: Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland . Each area was given a separate government with full authority except for specific issues (e.g. foreign affairs, world trade, currency, defense) that remained under the UK Parliament. The Northern Ireland Parliament met for the first time in 1921. The first election to the House of Commons in South Ireland in 1921 was viewed by Sinn Féin as elections to parliament for the revolutionary Irish Republic , which was unilaterally proclaimed in 1918 but never recognized. Sinn Féin won 124 of 128 seats, but at the first meeting of the Southern Irish Parliament in June 1921, only the 4 elected Unionists appeared (the elected Sinn Féin members instead gathered as the Second Dáil ), so that there is no mention of a Southern Irish government could.

In July 1921 a ceasefire was negotiated between British and Irish delegations and the Anglo-Irish Treaty marked the official end of the War of Independence . The treaty gave the southern Irish territory the status of a Dominion , similar to that of Canada . This went beyond what Parnell had been offered at the end of the 19th century and was slightly more than what the Irish Parliamentary Party had previously achieved through constitutional means. This treaty created the Irish Free State in 1922 , but Northern Ireland had the option to opt out of the treaty and remain part of the United Kingdom, which it eventually did. The secession from Northern Ireland was almost complete and the new border was set by a newly created Irish Boundary Commission .