HMHS Britannic

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

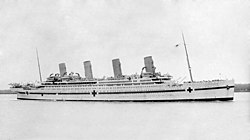

The HMHS ( H is M ajesty's H ospital S hip, German His Majesty hospital ship ) Britannic ( Engl. : [Bɻɪtænɪk] ) of the shipping company White Star Line was the third and final ship of the Olympic class and was like her sister ships Titanic and Olympic on built by the Harland & Wolff shipyard in Belfast . She was slightly wider and heavier than her two sister ships and differed in numerous additions in design.

On November 21, 1916, the Britannic - which could never be used as a passenger ship because of the First World War that had now started - ran into a German sea mine in the Aegean and sank. Of the 1,000 people on board, 30 lost their lives and 40 were injured. She was by far the largest ship that was sunk in the First World War.

Emergence

Planning and construction

The Britannic was built with some time lag to her two sister ships Olympic and Titanic in order to be able to incorporate experience with the two ships into her construction. The keel was not laid at the Harland & Wolff shipyard until November 30, 1911, more than two and a half years after the Titanic was keeled and shortly before its completion. Rumor has it that the third ship of the class was given the name Gigantic , which was changed to Britannic after the sinking of the Titanic . However, both the shipping company and the shipyard called this a legend. According to Simon Mills (owner of the Britannic wreck) and Tom McCluskie (shipyard historian at Harland & Wolff), Britannic is the only name that shipyard documents from October 1911, prepared more than six months before the Titanic accident . This contradicts the popular rumor that the name Britannic was only assigned after the sinking of the Titanic .

Later handwritten changes to the document from January 1912 relate to the width of the ship. The Britannic was widened by 46 cm compared to its sister ships in order to bring the distance between the center of gravity and the metacenter back into the area as with the Olympic despite additional superstructures . This change was therefore also planned before the sinking of the Titanic and has nothing to do with the double outer skin implemented later.

The Britannic's machinery corresponded in terms of its structure and functionality to that of its two sister ships, but was overall more powerful due to a larger boiler heating surface and a more efficient turbine. While Titanic and Olympic were registered nominally with 46,000 hp each, this value was 50,000 hp for the Britannic . For the last ship in the series, a cruising speed of 22 knots was assumed - for Titanic and Olympic , only 21 knots were set. Overall, the design of the propulsion system turned out to be a great success: the ships were able to reach respectable speeds with relatively low coal consumption. In fact, the power of the Britannic's machinery (as well as its sister ships) is likely to have been well beyond the nominal value of around 60,000 hp.

After the sinking of the Titanic in April 1912, construction work on the Britannic was initially stopped to await the results of the investigations into the disaster. Finally, significant technical changes were made to improve the ship's safety against sinking: the ship was given a double outer skin in the area of the boiler and engine rooms. Five particularly important bulkheads were extended up to the B-deck, so that the Britannic should still be buoyant with up to six flooded compartments. Furthermore, an additional bulkhead was built into the generator room, so that the Britannic had a total of 17 watertight compartments.

In order to enable a significantly more efficient evacuation of the ship in an emergency, a total of eight giant lifeboat crane pairs - six on the boat deck and two on the aft deck - were planned. Each of them could launch up to eight lifeboats at the same time. In total, the Britannic was to carry 48 lifeboats with a capacity of around 3600 people; a lifeboat place was now available for everyone on board. For use as a hospital ship , however, only five of these crane pairs were installed.

Due to these technically complex additions and changes, the construction of the ship was delayed, so that a maiden voyage was expected in the spring of 1915 instead of the previously hoped for spring 1914. On February 26, 1914, was Britannic in Belfast from the stack .

Furnishing

The interior of the Britannic would have been quite similar to that of its two sister ships, but the third and last ship of the class should still offer a significant increase in comfort through additional rooms that were not available on the Titanic and Olympic . A spacious children's playroom on the boat deck, an additional elevator for first class passengers , a hairdresser and a manicure studio as well as a gym for second class should be added.

In addition, the following major changes should be made:

- The unadorned swimming pool on Olympic and Titanic was to be fitted with wall and ceiling cladding made of polished wood and marble. In addition, elegant lighting fixtures were provided on the wall and ceiling for the room. Crucial for this change were the swimming pools of the competing German ships of the Imperator class , which were known for their extraordinarily magnificent, hall-like baths in the Pompeian style.

- The à-la-carte restaurant on the B-deck was to be stretched across the entire width of the ship and thus gain significantly in size. On the starboard side, directly accessible via the aft staircase, there was a large anteroom, which took up the style of the restaurant in terms of paneling and furnishings.

- A self-playing philharmonic organ made by the German manufacturer M. Welte & Sons was planned for the large first-class staircase in the front . However, because of the outbreak of war, this was not realized. The organ itself has been preserved and is now in the Museum for Music Automatons in Seewen, Switzerland . A revision was planned for parts of the railing decoration (arched handrails and partly modified wrought iron filigree). The pattern and color of the floor tiles differed significantly from those of the two sister ships.

- The cabins and suites of the first class were in large parts much more spacious than on the Titanic and Olympic . Almost all accommodations in this category had access to private toilets and bathrooms, which no other ship of the time could offer to this extent. In addition, two additional private salons were planned on the C deck, increasing the number of such rooms from four to six.The starboard promenade deck suite was to be extensively redesigned. Instead of the living room, it was given a private salon. In addition, the promenade was reduced by about half and renamed 'Verandah'. In addition, accommodation for the servants of the passengers in this suite as well as a kitchen were planned.

- The first-class smoking salon was also to be changed significantly: instead of the mother-of-pearl inlaid mahogany wall paneling as on Titanic and Olympic , this room was to receive wall panels with gold-plated carvings and a dome decorated with stained glass fields.

- The French café Parisien, which enjoyed great popularity on the sister ships but fell victim to the enlargement of the restaurant, was to be replaced by a terrace café on the A-deck (probably on the starboard side between the entrance to the large staircase and the lounge) .

A major difference to the sister ships was the roofing of the aft corrugated deck , which now also offered third-class passengers a weather-protected promenade.

Since the ship was never used as a passenger ship, a large part of the interior fittings that had already been made were stored. The shipyard auctioned them off in 1919, shortly after the end of the war. Parts of the paneling intended for the smoking room were installed in a hotel in England - without the gilding.

Dimensions

Although measured as a hospital ship with 48,000 GRT, it is considered likely that the Britannic would have been brought to over 50,000 GRT in passenger service by exploiting the leeway in the surveying regulations - an effective advertising measure to also allow a British ship to cross this "magical" border at the time to lift. Since 1913, the competing German HAPAG had ships of the Imperator class that were significantly larger than 50,000 GRT. For this reason, the length of the ship - in fact exactly the same as that of its sister ships (882 feet) - was often given generously as “around 900 feet” (about 274 m) in the public presentation. This is possibly the cause of the rumor that has been prevalent for many years, partly also in the specialist literature, that the Britannic was 903 feet long.

Use in the First World War

After the beginning of the war in August 1914, construction work on the Britannic was delayed because manpower and materials were needed for the armaments industry. After the tragic loss of the Lusitania in May 1915 and the increased need of the Royal Navy for transport space for the Gallipoli enterprise , it was decided to put the almost finished giant ship into service as a hospital ship. On November 13, 1915, the White Star Liner was requisitioned by the Admiralty and finally reported as operational on December 6, 1915.

By November 1916, the Britannic - identified as a hospital ship by a white paint with a green vertical stripe and several red crosses - made five voyages from the theaters of war in the Mediterranean to Great Britain, transporting large numbers of wounded. She was considered the best equipped hospital ship at sea. On November 12, 1916, the Britannic left Southampton with the destination Mudros in the Aegean Sea .

The downfall

On November 21, 1916, the Britannic headed for the Greek port of Mudros. A severe underwater explosion occurred in the channel between the islands of Kea and Makrónissos at 8:12 a.m. The cause could have been a torpedo hit. However, a hit by a sea mine of the German submarine U 73 is more likely .

Fatally, this explosion took place at a time when the crew was changing the guard . Although it was forbidden during the war, the water protection doors were opened for convenience (access to the departments was only possible via the emergency ladders when the bulkheads were closed). After the explosion, some of these doors in the bow no longer closed completely, probably their frames were slightly bent by the shock wave. As a result, it was no longer possible to limit the water ingress to the damaged compartments. The situation was made worse by a strong, uncorrectable list and numerous open portholes (it was also forbidden to leave portholes open during warfare) through which water could penetrate into the rear compartments, which increased the asymmetrical flooding.

The attempt by the captain Charles Alfred Bartlett to put the ship aground failed because the voyage forced even more water into the ship's leak. The Britannic sank in 58 minutes. Of the 1,036 people on board, 30 were killed and 40 injured, most of them in two lifeboats that had been unauthorized launched into the water while the engines were still running and were smashed by the propellers still turning .

One of those rescued was the nurse Violet Jessop , who had already been on board the Olympic when it collided with the British cruiser Hawke in 1911 , and who had also been one of the survivors of the Titanic disaster in 1912 . Violet Jessop was sitting in one of the two lifeboats that were being pulled into the still rotating propellers, but was able to jump out at the last moment. Although her head hit the keel of the sinking ship underwater, she still managed to surface so that the crew of another lifeboat could rescue her.

Except for the tragic incident with the first two lifeboats, the evacuation of the ship went very quickly and orderly, which can be seen from the low number of victims with a remaining time of less than 55 minutes.

It is partly believed that, despite her status as a hospital ship , the Britannic had loaded ammunition that could have caused a secondary explosion. A coal dust explosion was also considered to be a possible secondary explosion. However, given the type (early list, open portholes) and speed of the sinking, a secondary explosion is very unlikely, and there are no witnesses to this either. During numerous dives, no ammunition or weapons were found in any of the cargo holds or in the coal bunker. Also, no explosion can be seen in the coal bunker. The theses are therefore considered refuted.

The Britannic was the largest ship sunk in World War I and is still the largest sunk passenger ship in the world to this day.

The diver Richie Kohler describes in his book Mystery of the Last Olympian: Titanic's Tragic Sister Britannic ( ISBN 1-930536-86-0 ) the numerous dives of his expeditions to the wreck of the HMHS Britannic up to the year 2015. The divers came through the broken one Bow into the aisle for the machinists (English firemen's tunnel ) via boiler room 6 to boiler room 5 - through completely open bulkhead doors. No further advance was made, so it is not clear whether the bulkhead doors of the compartments further aft also remained open. This means that the Britannic was exposed to at least the same flooding as the Titanic due to the bulkhead doors being open . In contrast to this, however, the damage to the hull was not only around 1 m², but must have been much larger due to the mine hit. In connection with the - in contrast to the Titanic - open bulkhead doors, this explains why the Britannic sank much faster than its older sister despite the additional measures.

discovery

The wreck was discovered in 1976 by Jacques Cousteau and his diving team at the position 37 ° 42 ′ 5 ″ N , 24 ° 17 ′ 2 ″ E, at a depth of 120 Meters discovered.

The wreck lies on the side of the leak, so that the exact cause of the sinking can no longer be clarified today. However, anchors were discovered on the wreck during an expedition in 2003 that were used for German mines in World War I.

Movies

- Mathias Haentjes, director: ocean liners - golden years. Documentation about the era of the Atlantik-Liner , Germany, 2019, Radio Bremen , 52 min. (Image and film material about "Titanic", "Britannic" (wreck), from Cherbourg from Gare Maritime , from the Hapag-Hallen in Cuxhaven, to " Queen Mary 2 ", " Normandie ", " United States " - Philadelphia, " Ex-Astoria " - the oldest traveling pass.ship in this category. Information from the broadcaster arte , accessed on Feb. 27, 2020)

- Britannic (feature film, Great Britain / United States, 2000)

literature

- Eberhard Möller, Werner Brack: Encyclopedia of German U-Boats. From 1904 to the present. Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-613-02245-1 .

- Robert D. Ballard , Ken Marschall : Lost Liners - From the Titanic to Andrea Doria - the glory and decline of the great luxury liners . Wilhelm Heyne Verlag GmbH & Co., Munich 1997, ISBN 3-453-12905-9 (English: Lost Liners: From the Titanic to the Andrea Doria. The ocean floor reveals its greatest lost ships. Translated by Helmut Gerstberger).

- Britannic - Ship of a Thousand Days: The almost forgotten sister of the Titanic-Titanic-Verein Schweiz and Armin Zeyher

Web links

- The organ of the Britannic , Federal Office for Culture FOC

Individual evidence

- ↑ Linus Geschke: 100 years of "Britannic": A wreck, high hopes In: Spiegel online from October 11, 2016

- ↑ Largest Ships sunk or damaged. uboat.net, accessed November 22, 2016 .

- ↑ a b c Joshua Milford: What happened to Gigantic? Retrieved March 5, 2016 .

- ↑ Mark Chirnside: Gigantic Dossier. Retrieved March 5, 2016 .

- ↑ Christoph E. Hänggi: The Britannic Organ at the Museum of Music Automatons Seewen SO . Festschrift for the inauguration of the Welte Philharmonic Organ; Heinrich Weiss-Stauffacher Collection. Ed .: Museum for Music Automatons Seewen SO. Museum for Music Automatons, Seewen 2007.

- ^ Postcard with the dimensions of the Britannic (1914) corrected upwards .

- ↑ Postcard of the launch of the Britannic with the ship's dimensions corrected upwards (1914) .