Harry McNish

Harry McNish (also known as Harry McNeish or by the nickname Chippy ; born September 11, 1874 in Port Glasgow , Scotland , † September 24, 1930 in Wellington , New Zealand ) was a British ship carpenter and participant in the endurance expedition (1914-1917) to the Antarctic under the direction of the British polar explorer Ernest Shackleton .

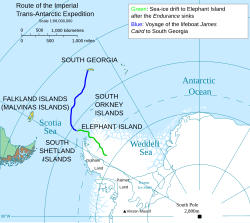

After the loss of the expedition ship Endurance, Nish was responsible for much of the work that was essential for the crew's survival. He rebuilt the dinghy, the James Caird , so that Shackleton and five men, including McNish, could travel hundreds of nautical miles to South Georgia to get help for the rest of the crew. During the phase of the voyage when the men dragged the boats across the pack ice, he briefly refused to follow the instructions of the expedition leader and was later one of the four crew members who were not awarded the Polar Medal .

After the expedition, he returned to England to serve in the merchant navy . Eventually he emigrated to New Zealand, where he worked as a dock worker in Wellington until his health forced him to retire. He died impoverished in the Ohiro Benevolent Home in Wellington.

Early life

Harry "Chippy" McNish was born in 1874 in the former Lyons Lane near the present library in Port Glasgow , Renfrewshire , Scotland . He was the scion of a large family and was born the third of eleven children. His parents were John and Mary Jane (nee Wade) McNish. His father worked as a shoemaker journeyman . McNish had strong socialist views, was a member of the United Free Church of Scotland, and abhorred foul language. He married three times: in 1895 Jessie Smith, who died in February 1898; 1898 Ellen Timothy who died in December 1904 and finally Lizzie Littlejohn in 1907.

There is some confusion about the correct spelling of his name. He is variously referred to as McNish, McNeish, or MacNish as in Alexander Macklin's expedition diary. The spelling “McNeish” is fairly common, for example in Shackleton's and Frank Worsley's accounts of the expedition and on McNish's tombstone, but “McNish” has been used widely and appears to be the correct version. On a signed copy of the expedition photo, the signature appears as “H. MacNish ”, but his spelling was generally somewhat peculiar, as can be seen from the diary he kept during the expedition. McNish's nickname is also not entirely clear: "Chippy" was a traditional nickname for a shipbuilder; both this variant and the shorter “chips” appear to have been in use.

Expedition Endurance

Endurance

The aim of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition was to cross the Antarctic continent from side to side for the first time .

At forty, McNish was one of the oldest members of the Endurance team (though Shackleton was seven months older). He suffered from hemorrhoids and rheumatism in his legs and was seen as strange and unqualified, but also respected as a carpenter - Worsley, the captain of the Endurance , called him an "excellent ship's carpenter". The pipe-smoking Scot was the only man on the crew Shackleton was "not sure of" about.

During the initial stages of the journey from Buenos Aires to Antarctica, McNish was busy with a number of routine tasks. He worked on the Nancy Endurance dinghy , built a small cabinet with drawers for Shackleton, sample cabinets for the biologist Robert Clark and instrument cases for Leonard Hussey , the meteorologist, and put up wind deflectors to protect the helmsman. He built a shelter for the extra coal that stretched between the puppet deck and the card room. He also took on the role of ship's hairdresser. As the ship pushed into the pack ice in the Weddell Sea , it became increasingly difficult to steer. McNish constructed a two-meter-high flagpole on the bridge so that the navigating officer could give the helmsman directions, and built a small platform at the stern so that the propeller could be observed and, if necessary, cleared of the ice.

When the ship finally got stuck in the pack ice, McNish's duties expanded to building makeshift housing and, once it was clear that the ship would sink over time, converting the sledges for the voyage across the pack ice to the open sea. He built the hut in which the crew had their meals ( The Ritz ) and cells in which the men could sleep. These too were given names; McNish shared The Sailors' rest with Alfred Cheetham , the third officer. With the help of the crew, he also built dog kennels on the upper deck. After the endurance got stuck and the men spent their time on the ice, McNish set up goal posts and football became a daily pastime. To pass the evenings, McNish played poker in the officers' mess with Frank Wild , Tom Crean , James McIlroy , Worsley and Shackleton.

The endurance finally began to draw water from the pressure of the ice . To prevent them from fully running, McNish built a cofferdam , which he with strips of cloth and sewing thread caulked . Even the dam couldn't prevent the pressure of the ice from eventually crushing the Endurance . When the ship went down, he was given the job of rescuing the goods from the former "Ritz". Under McNish's command, a few men opened the deck enough within a few hours to pull out a good amount of supplies.

On ice

One night while the crew was encamped on the ice, McNish broke off a small piece of the ice floe while on watch and was rescued by the intervention of the men from the nearest guard, who threw him a line to make him jump back onto the main floe could. Mrs. Chippy , the tomcat that McNish had brought on board, was shot together with several puppies after losing the Endurance , because they did not want to feed “wimps”. McNish apparently never forgave Shackleton for ordering this.

McNish suggested building a smaller vehicle from the wreckage of the Endurance , but was overruled; Instead, Shackleton decided to march across the ice to the water's edge and pull the three lifeboats with him. McNish had suffered from hemorrhoids and homesickness before the voyage properly started, and after the ship went down his frustration slowly grew. He vented by writing down his feelings in his diary and focusing on the expressions of his tent companions: “I was with men of all kinds on ships, both on sailors and on steamers, but never with some of our crew - where the dirtiest language is used as a sign of tenderness and, worse still, is even tolerated. "

While the sled was being dragged across the ice, McNish briefly rebelled and refused to take up his post in the harness, explaining to Frank Worsley that the crew was no longer obliged to give instructions since the ship's sinking to comply. The reports give mixed statements about Shackleton's reaction: some report that he threatened to shoot McNish; others that he read him the ship's paragraphs and made him understand that the crew was under his command until they reached a port. McNish's statement would normally have been correct: Duty to the captain (and payment) usually ended with the loss of a ship, but the articles the crew signed for that expedition included a clause that the men would agree to declared "to perform any duty on board, in the boats or on the coast as ordered by the captain". Otherwise McNish would have had no choice but to submit: he could not survive alone and not travel with the group until he obeyed orders. Shackleton finally decided it had been a mistake to try to pull the boats and decided that the only option was to wait for the ice to break that would bring the men to the open sea.

When the ice finally brought the camp out to sea, Shackleton decided that the three boats, the James Caird , the Stancomb Wills and the Dudley Docker should head for Elephant Island first . McNish had prepared the boats as best he could for a long voyage across the open seas, raising their borders to provide protection from waves.

Elephant Island and the James Caird

On the sea voyage to Elephant Island , McNish drove with Shackleton and Frank Wild in the James Caird . After the crew reached the island, Shackleton decided to continue with some men to South Georgia , where they would likely find whalers who could help rescue the rest of the crew. McNish was commissioned to make the James Caird seaworthy for the long voyage and should also go on board, possibly because Shackleton feared the effect it could have on the morale of the other men. McNish himself seemed glad to have a ride; the island and the chances of survival in the event of wintering did not convince him:

"I don't think there are ever many fine days on this forlorn island… I dont think there will be many survivers if they have to put in a winter here."

"I don't think there are many good days on this deserted island ... I don't think there will be many survivors if they have to spend the winter here."

McNish used the mast of one of the other boats, the Stancomb Wills , to reinforce the keel and to extend the small 6.7 meter long boat so that it could withstand the waves on the 1480 kilometer journey. He sealed it using a mixture of seal blood and flour, and made a makeshift frame from the wood and nails of the packing boxes and the runners of the sledges, which was covered with canvas.

When the boat was launched, McNish and John Vincent were thrown into the sea by a wave. Both were unharmed, albeit wet, and managed to swap a few clothes with the men who remained on the island before the James Caird left for good. The mood on board was cheerful and McNish wrote in his diary on April 24th:

"We took good bye with our companions. & set sail on our 870 miles to South Georgia for assistance ... we were in the open sea wet through but happy through it all. "

“We said goodbye to our companions. & set sail for our 870 miles to South Georgia ... we were on the open sea, drenched, but happy despite everything. "

The good mood did not last long: The conditions on board the small boat were harsh, the men persistently drenched and freezing. The six men split up into two guards, who each took on four-hour shifts: three of the men steered the boat, while the other three lay under the sheet and tried to sleep. McNish shared his watch with Shackleton and Crean.

South Georgia

The James Caird crew reached South Georgia on May 10, 1916, 15 days after they had left Elephant Island. You landed in Cave Cove on King Haakon Bay . She was on the wrong side of the island, but everyone was relieved to finally have landed; McNish wrote in his diary:

"I went to the top of the hill & had a lay on the grass & it put me in mind of old times at Home sitting on the hillside looking down at the sea."

"I went to the top of the hill & lay down on the grass & the old days came to my mind, sitting on the hill at home and looking down at the sea."

They found albatross chicks and seals to improve the feeding situation, but despite the relative comfort the island offered compared to the small boat, they still had to go to the Husvik whaling station on the other side of the island for help for the men Organize Elephant Island. It was clear that McNish and Vincent couldn't go any further, so Shackleton, under the care of Timothy McCarthy, left them in the tilted James Caird and set off on the journey over the mountains with Worsley and Crean. McNish removed screws from the James Caird and attached them to the boots of the men who would go into the mountains to improve their grip. He also made a simple sledge from the driftwood he found on the beach, but it turned out to be too bulky and heavy for practical use. Shackleton appointed McNish to lead the three men and instructed him to wait for relief and sail to the east coast at the end of winter if no one came. After Shackleton's group crossed the mountains and arrived in Husvik, he sent Worsley back on one of the whaling ships , the samson , to pick up McNish and the others. After seeing the emaciated and scarred McNish arriving at the whaling base, Shackleton noted that he felt that rescue had come just in time for him.

Polar medal

Whatever the true story of the rebellion on the ice, neither Worsley nor McNish ever mentioned the incident in writing. Shackleton omitted it completely in south , his report on the expedition, and only referred to it marginally in his diary: “ Everyone working well except the carpenter. I shall never forget him in this time of strain and stress ”(German:“ Everyone works well, except for the carpenter. I will never forget him during this time of strain and strain ”). However, on the drive to South Georgia, Shackleton was impressed by the carpenter's determination and spirit. Still, McNish's name appeared on the list of four men not suggested by Shackleton for the Polar Medal. Macklin felt the denial of the honor was unjustified:

“I was disheartened to learn that McNeish, Vincent, Holness and Stephenson had been denied the Polar Medal… of all the men in the party no-one more deserved recognition than the old carpenter…. I would regard the withholding of the Polar Medal from McNeish as a grave injustice. "

“When I heard that McNeish, Vincent, Holness and Stephenson had been denied the polar medal, I was dejected ... of all the men on the team, none would have deserved the credit more than the old carpenter ... I would consider it a grave injustice if that Polar medal withheld from McNeish. "

Macklin believed that Shackleton's decision could have been influenced by Worsley, who shared a mutual hostility with McNish and had accompanied Shackleton back from Antarctica. Members of the Scott Polar Research Institute , the New Zealand Antarctic Society and Caroline Alexander, the author of Endurance , have criticized Shackleton's rejection of McNish's award, and suggestions have been made to award him the medal posthumously.

Later life, memorials, and records

After the expedition, McNish returned to the Merchant Navy and worked on several ships. He often complained that his bones were in constant pain from the conditions on the James Caird voyage ; He reportedly sometimes refused to shake hands because of the pain. On March 2, 1918, he was divorced from Lizzie Littlejohn, at which time he had already met Agnes Martindale, his new partner. McNish had a son named Tom and Martindale a daughter named Nancy. Although she is mentioned frequently in his diary, it appears that Nancy was not McNish's daughter. He served a total of twenty-three years in the Navy during his lifetime, but eventually secured a position with the New Zealand Shipping Company . After making five trips to New Zealand, he moved there in 1925, leaving behind his wife and all of his carpentry tools. He worked in the Wellington waterfront until an injury ended his career. Destitute, he slept under a tarpaulin in the harbor shed and was dependent on monthly collections from the dock workers. He was given a place at the Ohiro Benevolent Home , but his health deteriorated until he died on September 24, 1930 in Wellington Hospital. He was buried with full naval honors in Karori Cemetery , Wellington , on September 26, 1930 ; the HMS Dunedin , which was just in port, provided twelve men for the fire team and eight pallbearers. Nevertheless, his grave remained unmarked for almost thirty years until the New Zealand Antarctic Society erected a tombstone on May 10, 1959. In 2001 it was reported that the grave was unkempt and overgrown with grass, but in 2004 the grave was meticulously manicured and contained a life-size bronze statue of McNish's beloved cat, Mrs. Chippy. His grandson Tom believes that this tribute meant more to him than receiving the polar medal.

1958 the named UK Antarctic Place-Names Committee after surveys by the South Georgia Survey the island McNish Iceland (originally McNeish Iceland ) in the Cheapman Bay off the south coast of South Georgia after him. On October 18, 2006, a small oval plaque was unveiled in the Port Glasgow library honoring his accomplishments; earlier that year he had been the subject of an exhibition at the McLean Museum and Art Gallery in Greenock . His diaries are kept in the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington.

Artistic reception

Harry McNish is at the center of the one-person play Lost in the Pack Ice - An adventurous tale of Ernest Shackleton's endurance expedition and the story of a mutiny by Christoph Busche. World premiere on January 27, 2018 at Theater Kiel (Theater im Werftpark), directed by Christoph Busche. It is shown how McNish initially admires the expedition leader Shackleton and enthusiastically sets off with the endurance . After the shipwreck, during the several month odyssey over the ice, McNish had increasing doubts until he turned against Shackleton.

further reading

- Caroline Alexander: Mrs. Chippy's Last Expedition: The Remarkable Journal of Shackleton's Polar-Bound Cat , Harper Paperbacks, 1999, ISBN 0-06-093261-9 - an account of the expedition from the point of view of McNish's cat, Mrs. Chippy.

- Heritage (Ed.): Ernest Shackleton - an account of McNish's story, told by “Mrs. McNeish ”(presumably Agnes Martindale).

- An article by John Thomson .

Web links

Notes and individual references

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Ernest Henry Shackleton: South! The Story of Shackleton's Last Expedition, 1914-1917 . Penguin Books, February 1, 2004 ( gutenberg.org ).

- ↑ a b 'Chippy' honored . Greenock Telegraph. Accessed on November 8, 2006. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c d e f Endurance Obituaries: Henry McNish . Endurance tracking project. 2005. Archived from the original on February 9, 2006. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved November 9, 2006.

- ↑ a b c Shackleton news . The James Caird Society. November 3, 2006. Archived from the original on October 26, 2006. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved November 8, 2006.

- ↑ Alexander Hepburne Macklin: Virtual Shackleton: Alexander Macklin's diary, of Shackleton's Imperial Trans - Antarctic Expedition (page) . Scott Polar Research Institute. July 29, 2004. Retrieved November 9, 2006.

- ↑ The Expedition: Beset . American Museum of Natural History. 2001. Archived from the original on September 25, 2006. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved November 8, 2006. (Identifies the accompanying diary entry as being from Henry "Chippy" McNish's diary )

- ↑ Antarctica Feature Detail: McNish Island . US Department of the Interior: US Geological Survey. September 25, 1998. Retrieved November 9, 2006.

- ↑ a b c d Tamiko Rex (Ed.): South with Endurance: Shackleton's Antarctic expedition, 1914-1917 . The Photographs of Frank Hurley. Bloomsbury, London 2001, ISBN 0-7475-7534-7 , pp. 10-31 .

- ↑ Navy slang . Ministry of Defense / Royal Navy. 2006. Archived from the original on January 27, 2009. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved November 17, 2006.

- ↑ Some Antarctic Nicknames . The Antarctic Circle. August 19, 2006. Retrieved November 8, 2006.

- ^ A b F. A. Worsley: Shackleton's Boat Journey . Pimlico, 1998, ISBN 0-7126-6574-9 .

- ↑ Before he was supposed to rebuild the boats, there was little doubt about his craftsmanship. Nobody ever saw him take any measurements, but according to Macklin he did a great job

- ↑ Shackleton's Voyage of Endurance: Meet the Team . PBS. March 2002. Retrieved November 8, 2006.

- ^ A b c Andrew Leachman: Harry McNish - An insight into Shackleton's Carpenter . New Zealand Antarctic Society. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved November 9, 2006.

- ↑ Michael Smith: Sir James Wordie, Polar crusader . Exploring the Arctic and Antarctic. Birlinn, Edinburgh 2004, ISBN 1-84158-292-1 , pp. 371 .

- ^ Roland Huntford : Shackleton . 1st edition. Carroll & Graf, New York 1998, ISBN 0-7867-0544-2 , pp. 774 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Alfred Lansing: Endurance: Shackleton's incredible voyage . Phoenix, 2000, ISBN 0-7538-0987-7 , pp. 304 (reprint).

- ↑ Thomas Orde-Lees: Shackleton's Voyage of Endurance: Diary of a survivor . PBS. 2002/03. Retrieved November 8, 2006.

- ^ Ernest Shackleton: south. The Macmillan Co., New York 1920, p. 81 - Internet Archive “ This afternoon Sallie's three youngest pups, Sue's Sirius, and Mrs. Chippy, the carpenter's cat, have to be shot. We could not undertake the maintenance of weaklings under the new conditions. ”

- ↑ a b c d e Kim Griggs: Antarctic hero 'reunited' with cat . BBC . June 21, 2004. Retrieved November 7, 2006.

- ↑ a b c Tending Sir Ernest's Legacy: An Interview with Alexandra Shackleton . PBS. March 2002. Retrieved November 8, 2006.

- ↑ Shackleton's Legendary Antarctic Journey: The Great Boat Journey . American Museum of Natural History. 2001. Archived from the original on September 25, 2006. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved November 14, 2006.

- ↑ Shackletons' Voyage of Endurance: Timeline . PBS. 2002/03. Retrieved November 17, 2006.

- ↑ Caroline Alexander: The Endurance: Shackleton's legendary Antarctic expedition . Bloomsbury, London 1998, ISBN 0-7475-4123-X , pp. 211 .

- ↑ a b Jim McBeth: Forgotten Scot of the Antarctic . Sunday Times - Scotland. January 15, 2006. Retrieved November 9, 2006.

- ↑ "Woman" in the source probably refers to his life partner Agnes Martindale

- ^ New Zealand . The Dunedin Society. November 3, 2006. Archived from the original on July 1, 2007. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved November 8, 2006.

- ↑ Ryan, Jenny: Final resting place lies in a sad state . In: Dominion Post , Jan. 12, 2001, p. 14.

- ^ Antarctic Gazetteer . Australian Antarctic Data Center. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved November 9, 2006.

- ↑ Lost in the pack ice - Theater Kiel . In: @TheaterKiel . ( theater-kiel.de [accessed on June 5, 2018]).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | McNish, Harry |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | McNeish, Harry; Macnish, Harry; McNeish, Henry; McNish, Henry; Chippy |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British carpenter on the Endurance expedition |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 11, 1874 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Port Glasgow , Scotland |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 24, 1930 |

| Place of death | Wellington , New Zealand |