Blood of christ

The blood of Christ denotes in Christian theology

- the blood of Jesus Christ given on the cross for the salvation of mankind,

- the sacrament of the Eucharist under the form of wine .

The veneration of the holy blood was connected in many places with blood relics and the belief in a blood miracle and was the focus of a liturgical festival of ideas .

theology

In late Judaism and in the New Testament , the pair of terms “flesh and blood” denotes the entire human being in his perishable nature ( Sir 14.18 EU , 17.31 EU ; Mt 16.17 EU ; Joh 1.13 EU ) and thus also the constitution that the Son of God accepted at his incarnation ( Heb. 2.14 EU ).

Like all religions of antiquity, the religion of Israel also recognized blood as a sacred character, because in blood is life ( Lev 17:11 , 14 EU ; Dt 12:23 EU ), and everything that is related to life is closely related to God, the only Lord of life. This leads to three consequences: the prohibition of murder, the prohibition of the consumption of blood, the use of blood in cult.

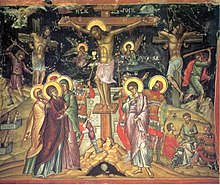

The New Testament ties in with the ancient cult of blood and transfers the aspects of atonement and union through blood into Christian symbolism . The blood is now primarily of significance as the blood of Jesus ( Rom. 3.25 EU ; Heb. 9.7 EU , 13.11 EU ). Through the blood of Christ , God's covenant with human beings ( Isa 53.12 EU ) is renewed ( Lk 22.20 EU ). God offers man the forgiveness of his sins ( Mt 26.28 EU and Mk 14.24 EU ). In the presentation of the Gospel of John , water and blood flowed from the side of Christ pierced by the lance at the crucifixion ( Jn 19 : 31-37 EU ) as a double testimony of God's love that confirms the testimony of the Spirit ( 1 Jn 5 , 6-8 EU ).

In this sense, the blood of Christ is drunk at the Eucharist as a sign of the renewal of the covenant and the forgiveness of sins (also Jn 6,53–54 EU ; 1 Cor 10:16 EU ). And precisely in seeing Christ's death as the last (one-time) sacrifice ( Rom. 6.10 EU ; Heb. 7.27 EU , 9.12 EU , 10.10 EU ), the rejection of other, further sacrifices is justified ( Wolfgang Trillhaas ). In addition, this is (depending on the Christian understanding) a self-sacrifice or a sacrifice of God (who sacrifices his son) and implies the abolition of blood revenge .

At the last supper with his disciples on the evening before his execution on the cross, Jesus made bread and wine permanent signs of his presence in the Christian community, and he interpreted the bread as his body and the wine as his blood: “He took the cup, spoke the thanksgiving prayer and handed it to the disciples with the words: All drink from it; that is my blood, the blood of the covenant, which is shed for the forgiveness of sins for many. ”( Mt 26 : 27-28 EU ) The transubstantiation of wine into the blood of Christ has been the central mystery of the Eucharist ever since . In the case of the Eucharist, drinking wine, in which the blood of Christ is seen, - especially in Eastern Church and modern Western theology - also means the union of man with God and participation in his divine being. With such an understanding of the Lord's Supper, e.g. B. With Michael Rau, one sees in the "Blood of Christ" not the blood of atonement, but as in the Old Testament the life of God or the Spirit of God.

However, analogies were found in the early church that saw atonement in the death of the righteous ( 4 Makk 6 : 28-30, 17:22). Last but not least, this is where martyrdom , which is also called “baptism of blood” (with reference to Lk 12.50 EU , Joh 19.32 EU , 1 Joh 5,6 EU, described in: Tertullian , de bapt. 16; Cyprian , Ep . 73,22).

Feast of the Precious Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ

The festival of the Precious Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ (Festum Pretiosissimi Sanguinis Domini Nostri Jesu Christi ) was a so-called festival of ideas that has been celebrated annually on July 1st in the Roman Catholic Church since the middle of the 19th century. The festival emerged from numerous regional Holy Blood festivals, which in connection with the veneration of a blood relic in the 11th / 12th. Century in Italy and France and in the 14th century in over 100 places in Germany. From 17./18. In the 19th century, Holy Blood festivals were also celebrated independently of local blood relics.

Pope Pius IX In 1849, in gratitude for his return from exile in Gaeta, added the feast of August 10 to the general Roman calendar ; Pope Pius X moved it to July 1. The reading texts in the Holy Mass were Heb 9.11–15 EU and John 19.30–35 EU . In the calendar reform after the Second Vatican Council in 1970, the festival was omitted because it was seen as a duplication of Corpus Christi , the festival of the holiest body and blood of Christ.

Blood miracles and blood relics

Numerous blood miracles of the Eucharist (e.g. in Bolsena ) or of martyrs (e.g. Januarius in Naples) also date from the Middle Ages . According to medieval belief, the martyr's mortal remains formed a deposit of his supernatural powers. Even after the soul had left the body, a supernatural power was still ascribed to the body, and blood was considered to be the most desirable carrier. The same is true (the Blood of Christ), which like other for Holy Blood relics Relics associated with Jesus ( crown of thorns , spear , nails, Cross ), discovered since the 4th century, were increasingly spent from about 800 to Europe. The height of the veneration of blood relics took place during the Crusades, but blood relics were brought to Europe from the Holy Land until the late Middle Ages. The veneration of blood relics rose again after the Thirty Years' War , when the suffering Christ gained importance as a motive for veneration. The legends of the blood relics tie in with the opening of the body of Christ, the preparation and embalming of the corpses by Joseph of Arimathia and Nicodemus and the participation of Mary and Mary Magdalene at the funeral. The holy blood cult became popular through pilgrimages to the blood relics and special indulgences .

The so-called Heilig-Blut-Tafel from 1489 from the monastery church of Weingarten Abbey contains the oldest pictorial representation and the oldest vernacular translation of the Holy Blood story in the German-speaking area: "Here after volget die histori des hailgen pluotz cristi / like the zelest in dis willig gotzhus come sy. On the first / like the knight longinus our lord sin syten opens with the / and touches his finstri ougen with the flowed out / pluot cristi and wd Gesechind and vowed. item… ”(“ The following is the story of the Holy Blood of Christ, how the relic got into this worthy place of worship. First [one sees] how the knight Longinus opens the side of our Lord with the [spear] and his blind eyes with the touched the poured out blood of Christ and seeing and believing ”).

Holy blood relics are worn in many places, among other things, during horseback processions, so-called blood rides , for worship through towns or corridors.

See also

- Body of Christ

- Patronage: Holy Blood Church , Neukirchen Monastery near the Holy Blood

- Missionaries of the Precious Blood , Missionaries of the Precious Blood

Web links

- Matthias Altmann: Forgotten or Abolished: Unknown Church Holidays. In: kathisch.de . 15th September 2019 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michael Rau: There is life in blood! - A critical demand for the biblical justification of the theological thought pattern of the “substitute atonement”. In: Deutsches Pfarrerblatt. Issue 3/2002, pp. 121-124, ISSN 0939-9771 ( pfarrerverband.de ).

- ↑ Hansjörg Auf der Maur : Celebrations in the rhythm of time I. Gentlemen's festivals in week and year (= Hans Bernhard Meyer (Ed.): Church service. Handbook of liturgical science. Part 5). Regensburg 1983, ISBN 3-7917-0788-4 , p. 194 f.

- ↑ Johannes Heuser: Holy Blood in Cult and Customs of the German Cultural Area. [Bonn] 1948, p. 44 ff. DNB 481653996 (Dissertation University of Bonn , Philosophical Faculty, August 12, 1948).

- ^ Norbert Kruse, Hans Ulrich Rudolf: 900 years of veneration of the Holy Blood in Weingarten 1094–1994. J. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1994, ISBN 3-7995-0398-6 , p. 17 f.