Hermynia to the mills

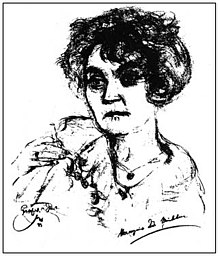

Hermynia Isabelle Maria Zur Mühlen , also Hermynia zur Mühlen , née Hermine Isabelle Maria Folliot de Crenneville (born December 12, 1883 in Vienna , Austria-Hungary , † March 20, 1951 in Radlett , Hertfordshire , Great Britain ) was an Austrian writer and translator .

Early years

Hermynia zur Mühlen was born as Countess Hermine Isabelle Maria Folliot de Crenneville in Vienna . She was the daughter of the diplomat Viktor Graf Folliot de Crenneville-Poutet . The family came from the nobility of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

Hermynia spent her childhood and youth in the Salzkammergut . In addition, she accompanied her father on extensive trips to the Middle East and Africa. She lived temporarily in Constantinople, Lisbon, Milan and Florence and learned numerous languages. Hermynia initially received her school education through private lessons, then attended the Sacre Cœur in Algiers and later a boarding school for older daughters in Dresden.

In 1901, Zur Mühlen passed her exams as a primary school teacher in Ebensee, Upper Austria . In 1905 he worked in a book printing company . Against the express wishes of her parents, she married the Baltic German landowner Victor von zur Mühlen in 1908 and followed him to his estate in Eigstfer (now Eistvere , Imavere municipality , Viljandi district ) in present-day Estonia . The marriage was very unhappy, and according to Patrik von zur Mühlen, Hermynia divorced her husband in 1920.

In 1913 she met the young poet Hans Kaltneker , with whom she translated poems. In the Baltic States she was appalled by the lack of possessions of the native Estonian and Livonian rural population. From 1914 Hermynia zur Mühlen suffered from tuberculosis . Several stays to relax in the climatic health resort Davos between 1914 and 1919 should help alleviate the disease. There she followed the October Revolution of 1917 in Russia with great sympathy . In 1919 Hermynia moved to Germany. She joined the communist movement and joined the KPD . She lived in Frankfurt am Main and Berlin with her partner and future husband, the translator and journalist Stefan Isidor Klein (1889–1960) of Jewish origin . She published numerous essays in the communist and social democratic press, especially in Die Rote Fahne and Der Revolutionär .

Writer and publicist

In 1921 she published her proletarian fairy tale Was Peterchen's friends, illustrated by George Grosz , in Berlin's Malik publishing house . She is the author of short stories and novels, often with anti-fascist and time-critical content. She wrote radio plays, detective novels, books for children and young people, and other prose. Sometimes she wrote under the pseudonyms Franziska Maria Rautenberg, Traugott Lehmann and Franziska Maria Tenberg. In the course of her life she translated about 150 novels and short stories from French , Russian and English into German , including works by Upton Sinclair . The "red countess" became one of the most famous communist columnists and journalists of the Weimar Republic .

Because of her propaganda story Schupomann Karl Müller (1924) playing in the police environment , Hermynia zur Mühlen was charged with treason in Germany , but acquitted in 1926. In 1929 her novel End and Beginning was published , which became a great literary success. Other autobiographical novels such as Das Riesenrad (1932), Reise durch ein Leben (1933) and Forge of the Future (1933) followed.

In 1934 the novel Our Daughters, the Nazines appeared in continuation in the magazine Deutsche Freiheit in the autonomous Saar area .

In a well-received letter to her publisher in 1933, she wrote: “Since I do not share your view that the Third Reich is identical to Germany (...), I cannot reconcile it with my convictions or my sense of cleanliness, the unworthy example of the Four gentlemen named by you ( Alfred Döblin , René Schickele , Stefan Zweig and Thomas Mann stopped working on the collection magazine attacked by the National Socialists ), who seem to be more interested in the newspapers of the Third Reich, in which they do not live wanting to be printed and sold by the booksellers as being true to their past and beliefs. ... "

Flight and Exile

With the seizure of power of the Nazis in Germany Hermynia moved to mills in 1933 returned to Vienna, where she is a member of the National Federation of Socialist writer was. The Nazi regime put her works on the list of harmful and undesirable literature .

In Vienna she warned against fascism , but increasingly distanced herself from the KPD. She continued to work in the left democratic exile press and as a writer. After the annexation of Austria in March 1938, Hermynia zur Mühlen and Stefan Klein fled to Bratislava; there they married. After the destruction of the rest of the Czech Republic (March 1939) both emigrated to England. There, too, she continued her literary work. With “Little Stories from Great Poets” she consolidated her reputation as a prose writer in children's and young adult literature.

The couple lived in London until 1948, then - impoverished and seriously ill - north of the British capital. Until her death, Hermynia zur Mühlen published further works in German and English as well as translations, but without receiving much attention. In 1945 her works were received again in Austria and Germany in the context of communist and social democratic literature - several of her books were reprinted by the KPÖ's Globus publishing house - but they were soon forgotten.

Your estate is considered lost.

Works (selection)

- Young girls literature contribution in: Die Erde 1 , 1919, p. 473 f.

- What Peter's friends tell . 6 fairy tales, 1921.

- The monkey and the whip . In: Der Junge Comrade 2 , 1922.

- The blue ray . Roman, 1922.

- The rose bush . Fairy tale, 1922.

- Why . Fairy tale, 1922.

- The little gray dog . Fairy tale, 1922.

- The temple . Roman, 1922.

- Light . Roman, 1922.

- The sparrow . Fairy tale, 1922.

- Ali, the carpet weaver . 5 fairy tales, 1923.

- The lock of truth . A storybook. With Karl Holtz (illustrations). Verlag der Jugendinternationale, Berlin-Schöneberg 1924.

- End and beginning . A book of life. S. Fischer, Berlin 1929 (autobiography).

- Once upon a time ... and it will be . Fairy tale. With illustrations by Heinrich Vogeler . Verlag der Jugendinternationale, Berlin 1930. (Facsimile print of this edition with an afterword by Karl-Robert Schütze, Berlin 2001).

- The ferris wheel . Novel. Engelhorn, Stuttgart 1932.

- Nora has a great idea . Novel. Gotthelf, Bern / Leipzig 1933.

- Journey through a lifetime. Gotthelf, Bern / Leipzig 1933.

- A year in the shade . Novel. Gutenberg Book Guild, Zurich / Vienna / Prague 1935.

-

Our daughters, the Nazins . Novel. Gsur-Verlag, Vienna 1938.

- New edition of Aufbau-Verlag , East Berlin , 1983, DNB 840399618

- New edition ed. and with an afterword by Jörg Thunecke. Promedia, Vienna 2000, ISBN 978-3-85371-165-1 .

- Little stories from great poets . Globus Verlag, Vienna 1946 (book series “Youth Ahead”).

- What Peter's friends tell. Fairy tale . Globus Verlag, Vienna 1946 (book series “Youth Ahead”).

- A bottle of perfume. A little humorous novel . Schönbrunn-Verlag, Vienna 1947.

- When the stranger came. Novel . Vienna: Globus-Verlag, Vienna 1947.

- The ferris wheel . Austrian book club, Vienna 1948.

- When the stranger came . Novel. Structure, Berlin 1979.

- The sparrow . Fairy tale. Ill .: George Grosz, John Heartfield, Karl Holtz, Rudolf Schlichter, Heinrich Vogeler. The children's book publisher, Berlin 1984.

- The white plague . Novel. The grandstand, Berlin 1987.

- Once upon a time ... and it will be . Three fairy tales. Initiative against xenophobia, racism and anti-Semitism, Vienna 1991.

- Eternal shadow play . Novel. Ed., Nachw .: Jörg Thunecke. Promedia, Vienna 1996, ISBN 978-3-85371-114-9 .

- Drive into the light . Stories. Foreword by Karl-Markus Gauß . Sisyphus, Klagenfurt 1999.

- Dear comrade, the Maliks have decided ... , Wieland Herzfelde , Hermynia zur Mühlen, Upton Sinclair , letters 1919–1950, Bonn 2001.

- Fourteen helpers and other novels from exile. Edited by Deborah Vietor-Engländer. Peter Lang, Bern 2002.

- Side luck: selected stories and feature pages from exile. Edited by Deborah Vietor-Engländer. Peter Lang, Bern 2002.

- Works. Selected and edited by Ulrich Weinzierl on behalf of the German Academy for Language and Poetry and the Wüstenrot Foundation , with an essay by Felicitas Hoppe . Paul-Zsolnay-Verlag, Vienna 2019, ISBN 978-3-552-05926-9 (4 volumes).

literature

- Manfred Altner: Hermynia to the mills. A biography . Peter Lang, Bern 1997.

- Hermann Bahr : Diary. February 20 in: Neues Wiener Journal , 38 (1930) # 13031, 16. (March 2, 1930) (review of the end and beginning )

- Beate Frakele: "I as an Austrian ...". Hermynia Zur Mühlen (1883–1951) . In: Johann Holzner u. a. (Ed.): A difficult homecoming. Austrian literature in exile 1938–1945 . Institute for German Studies, University of Innsbruck (= Innsbruck contributions to cultural studies: German series; 40), pp. 373–383.

- Karl-Markus Gauß : Hermynia zur Mühlen or No way back from Hertfordshire . In: Ders .: Ink is bitter. Literary portraits from Barbaropa . 2nd edition. Wieser, Klagenfurt / Salzburg 1992, pp. 160-173.

- Elisabeth Humer: Hermynia to the mills. The detective novels . Dipl.-Arb. Univ. Vienna 2006.

- Susanne Matt: Hermynia Zur Mühlen (1883–1951). From the proletarian-revolutionary writer to the writer of entertainment literature . Dipl.-Arb. Univ. Vienna 1986.

- Helmut Müssener: "We are building, mother". How one imagined the "inside" "outside". About Hermynia zur Mühlen's novel "Our Daughters, the Nazins" . In: Edita Koch / Frithjof Trapp (eds.): Conceptions of Realism in Exile Literature between 1935 and 1940/41. Conference of the Hamburg Office for German Exile Literature 1986 . Edita Koch, Maintal 1987 (= exile; special volume 1), pp. 127–143.

- Elisabeth Barbara Platzer: Hermynia Zur Mühlen as a fairy tale author. A contribution of the proletarian revolutionary children's and youth literature . Dipl.-Arb. Univ. Graz 1991.

- Barbara Scheriau: The development of the image of women in the work of the writer Hermynia Zur Mühlen (1883–1951) . Dipl.-Arb. Univ. Vienna 1996.

- Eva-Maria Siegel: “Young people run after anyone who hits the drum. Why can't good things beat a drum? ”Reflections on a novel by Hermynia Zur Mühlen and her way into British exile , in: Bolbecher, Siglinde / Kaiser, Konstantin / McLaughlin, Donal / Ritchie, JM (eds.): Literatur und Kultur des Exile in Great Britain. Verlag für Gesellschaftskritik, Vienna 1995 (= Zwischenwelt, Vol. 4), pp. 129–140.

- Herbert Staud: On the 100th birthday of Hermynia Zur Mühlen . In: iwk 4 (1983), pp. 94-96. [reprinted in: Weg und Ziel 42/4 (1984), pp. 154–156.]

- Deborah Vietor-Engländer : Hermynia Zur Mühlen's fight against the 'Enemy Within: Prejudice, Injustice, Cowardice and Intolerance' , in: Keine Klage über England? German and Austrian exile experiences in Great Britain 1933–1945, ed. by Charmian Brinson , Richard Dove, Anthony Grenville, Marian Malet and Jennifer Taylor. iudicium Verlag, Munich 1998 (Publications of the Institute of Germanic Studies, University of London School of Advanced Study, Vol. 72), pp. 74–87.

Web links

- Literature by and about Hermynia Zur Mühlen in the catalog of the German National Library

- Entry on Hermynia Zur Mühlen at litkult1920er.aau.at , a project of the University of Klagenfurt

- Pictures and documents about Hermynia zur Mühlen

- Genealogical manual of the Baltic knighthoods Part 1, 1: Livland, Görlitz, 1929, p. 272

- Entry in the Herbert Exenberger archive of the Theodor Kramer Society

- Jörg Thunecke: Portrait module on Hermynia Zur Mühlen at litkult1920er.aau.at , a project of the University of Klagenfurt

- Late rediscovery

Individual evidence

- ↑ Stefan Isidor Klein , in detail in the Germersheim Translator Lexicon UeLex

- ↑ Banished Books: Online publication of the list of writings forbidden by the National Socialists

- ^ Wilhelm Kuehs (2002): Hermynia Zur Mühlen (1883–1952) , p. 1.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | To the mills, Hermynia |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Zur Mühlen, Hermynia Isabelle Maria (full name); To the mills, Hermynia; Folliot de Crenneville, Hermine Isabelle Maria (maiden name); Rautenberg, Franziska Maria (pseudonym); Tenberg, Franziska Maria (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian writer and translator |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 12, 1883 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vienna , Austria-Hungary |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 20, 1951 |

| Place of death | Radlett , Hertfordshire , UK |