Erkrath-Hochdahl

|

Hochdahl

City of Erkrath

|

|

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 51 ° 12 ′ 28 " N , 6 ° 57 ′ 25" E | |

| Height : | 75 m |

| Area : | 11.72 km² |

| Residents : | 27,921 (Nov. 30, 2017) |

| Population density : | 2,382 inhabitants / km² |

| Incorporation : | 1st January 1975 |

| Postal code : | 40699 |

| Primaries : | 02104, 02129 |

Hochdahl (until 1938 Millrath) is the largest and eastern part of the city of Erkrath in the Mettmann district . The Sedentaler Bach flows through the village. In August 2016, Hochdahl had 27,427 inhabitants on an area of 11.72 km².

These are remarkable Planetarium in Mansion (one of only eight planetarium in England), and the references place of Neanderthaloid in Neandertal .

history

In the pre-industrial times, Hochdahl was, in contrast to Erkrath, not a village, but just a collection of a few farms. These were operated under the name Millrath until 1938. They belonged to the parish of Erkrath and were taxable to the house of Unterbach. The administration was initially incumbent on the Mettmann Office (until 1806), then the Mayor's Office Haan (until 1894) and then the Mayor's Office, later the Office, Gruiten .

The earliest known mention of the name, as Milroyde , dates back to 1218. Perhaps it was the clearing of a settler named Milo. It was not until 1658 that the village was recorded on maps under the name Mulrad . The assumption that the place name suggests the existence of a mill is therefore unlikely.

Far older is the Schlickum farm (mentioned in 1050), which possibly dates back to the 9th century. During this time , a noble Rodsten gave the Werden monastery a mansus (60 acres) as a gift. Like Hrotsteninghuson (Rützkausen, Wülfrath ) and Wordincbeke (Wordenbeck), this district was on the Strata Coloniensis . Around the time of the Knights of Ulenbruch, who had owned the estate since 1384, the farm association extended to Hilden, Haan and Gruiten.

The names Ym Dale (first 1392) and Uf dem Dahl (1416) probably both mean the Hochdahler Hof. While the Eickenberg (1189), Karschhaus (before 1498), Stolls, Falkenberg, Thekhaus, Kleff and others courtyards are often only reminiscent of street names, the mountain station of the same name on the Erkrath steep ramp was built near the Hochdahler Hof (which was demolished in 1969) in 1841 . Hochdahl and with it the Düsseldorf – Elberfeld railway line went into operation. An iron ore deposit was discovered during the construction of the line; To exploit it, a steelworks was built in 1848, which was in operation from 1849 to 1912. In 1871, at the height of its productivity, four blast furnaces , twelve blast heaters and 136 coke ovens were in operation. The director was Julius Schimmelbusch , a hut doctor, and for a time also a member of the Millrath council, was Professor Karl Sudhoff . There were also blacksmiths, several lime kilns, and later brickworks and weaving mills.

With commercial and industrial settlement, the residential population increased. In 1876 the Catholic Church of St. Francis in Trills was consecrated. Ten years later it received a three-part ringing of bronze bells from the renowned Otto bell foundry from Hemelingen / Bremen. It has the strike tone series es - f - g and is one of the oldest still completely preserved Otto bells. In 1905 the Protestant Neander Church was inaugurated on the Neanderhöhe. However, Erkrath grew faster at first. The part of Hochdahl located on the railway line west of Millrath, today unofficially Alt-Hochdahl , became part of the newly founded Mayor's Office Erkrath in 1898. When the districts of the Rhine Province were reorganized in 1929, Hochdahl was again spun off from the mayor's office and combined with the rest of the Millrath areas. The community of Millrath was renamed Hochdahl in 1938.

New town of Hochdahl

Today's Hochdahl emerged from the early 1960s under the name Neue Stadt Hochdahl as a planned city and relief city for Düsseldorf . The project was one of the largest urban development projects in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. The development company Hochdahl (EGH) was founded in December 1960 to carry it out. The EGH bought up land, had many old buildings demolished and a completely new town was built over the course of four decades. The first urban planning concepts were developed by the city planner Professor Aloys Machtemes and later adapted to changed framework conditions by the office of Kuhn, Boskamp and Partner in the 1960s. In the first plan, multi-storey apartments that traced the topography of the site enclosed the single-family houses in a ratio of one to one. Due to the high demand of mostly young families for cheap living space and the pressure of the construction industry , the proportion of multi-storey apartments increased to 80%. High-rise buildings were also built. Several multi-lane streets that crossed old settlement centers and a 20,000 m² shopping center were planned. Large nature conservation areas (Bruchhauser Feuchtwiesen, Majewski clay pit) should be given up, and the new town of Hochdahl should have a population of up to 50,000. Protests from the citizenry prevented this. From the mid-1970s, the plans were changed to the extent that old substance should be preserved. Excessive residential and commercial construction was pushed back, more emphasis was placed on preserving the natural living environment. In 1977 the much smaller Hochdahler Markt was built as a village center and expanded in the following decades to include various construction sections (Karschhauser Strasse, Bast -zeile, Arkaden). The urban development project is considered completed.

The neighborhoods , small settlements and courtyards were connected with each other in the period after 1972. Hochdahl became a cohesive suburb . The old settlements (Alt) -Hochdahl, Trills, Millrath, Willbeck, Kempen and Sandheide were merged. Until 1974, Hochdahl, with the much smaller villages Gruiten (today a district of Haan ) and Schöller (today a district of Wuppertal ), was part of the Gruiten administrative office .

Merger with Erkrath

In the course of the municipal reorganization of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia in the 1970s, when the administrative authorities were abolished and many municipalities lost their independence, Hochdahl and Erkrath and smaller parts of the municipalities of Hilden and Haan were replaced by Section 19 of the Düsseldorf Act with effect from 1. January 1975 merged to form the new town of Erkrath. According to the will of the state capital Düsseldorf, Hochdahl and Erkrath should be incorporated into the state capital. The communities fought vehemently against any wishes for incorporation. Different models of thought were devised by politicians and then rejected. It became apparent that independence could not be obtained. A bill by the North Rhine-Westphalian Minister of the Interior in December 1973 finally provided for Hochdahl to be united with Erkrath, in return for which the Erkrath district of Unterbach was to be reclassified to Düsseldorf. Eickert, which originally belonged to Haan, was awarded to Hochdahl, and thus to the new town of Erkrath. The Hochdahler parties seized this opportunity immediately. The idea was even born to merge Hochdahl and Eickert to form the city of Neandertal , which, however, could not be realized because of Erkrath's refusal. Thus, on January 1, 1975, Hochdahl became a district of Erkrath. Although Erkrath had fewer inhabitants than Hochdahl, which had grown considerably due to the large building projects, Erkrath was the namesake of the community because of the town charter.

The city of Düsseldorf, which was still very interested in the incorporation, succeeded in persuading the North Rhine-Westphalian Interior Minister Burkhard Hirsch to submit a new draft law aimed at incorporating Erkrath with Hochdahl in Düsseldorf. The chances of becoming self-employed were poor. Many members of the state parliament wanted to finally end the subject after many years. At a hearing of the Interior Minister in Erkrath in 1976, massive protests from all parties and institutions were loud. Erkrath received great support from the Mettmann district, which had to fear for its own existence if Erkrath broke off. In April 1976, the state parliament voted for Erkrath's independence with a two-vote majority, thereby ending the discussion. Due to the 19,104 inhabitants of Hochdahl, the city grew to 36,283 citizens. In October 1987, Dusseldorf's demands for restructuring were again loud, seeking new development opportunities for the state capital in the region. However, the then Interior Minister Herbert Schnoor rejected this request .

The role of the Hochdahl market

In 1965 there was an ideas competition for the design of the main center of the Neue Stadt Hochdahl, but the result was an unrealizable plan. A highly complicated structure with a large selection of shops that far exceeded daily needs. This competition exactly reflected the conflict between planning requirements and realizable investments. It was also out of the question, because it was feared that the center of a relief city could not compete with much larger shopping centers like in Düsseldorf. In addition, the Hochdahl transport network was not built for such a high level of traffic. Finally, another offer from the French group SCC, which wanted to build a shopping center with a size of 45,000 m² in Hochdahl, was rejected. In summary, it can be said that Hochdahl deliberately opted for a small range of shopping options, as it would not have suited the area and it was assumed that it could not financially withstand the competition from larger cities. The market, which was built in 1979 and expanded in 1987, was adapted to the prevailing conditions: shops for daily needs, medical centers, a post office, several banks, a registration office, the ecumenical house of churches , varied restaurants and other service providers rounded off the multifunctional center. Five bus lines go to the Hochdahler Markt stop. From the end of 2009, the Hochdahler Markt was renovated. The old floor covering was worn out and posed a not inconsiderable risk of injury. In addition, the insulation had been attacked by the trees planted in the 1980s, so extensive renovation was inevitable.

Infrastructure

In Hochdahl there are five primary schools, a secondary school, a secondary school, the Hochdahl grammar school and a boarding school. The community center on Hochdahler Markt, opened in 1980, functions as a community center, which at the time of its opening was one of the most modern and futuristic community centers in North Rhine-Westphalia. On the outskirts is the observatory of the Neanderhöhe observatory , which also operates the nationally known planetarium in the community center. A swimming pool from the 1970s has now been demolished, instead the Neanderbad, which opened in 2006, is located centrally between the districts of Erkrath and Hochdahl.

In 1970, lunar rocks brought from the Apollo 11 and Apollo 12 lunar missions were exhibited in Europe for the first time in the rooms of the Neanderhöhe Hochdahl observatory.

The Erkrath-Hochdahl Railway and Local History Museum is located on the site of the former Hochdahl station .

Rail transport

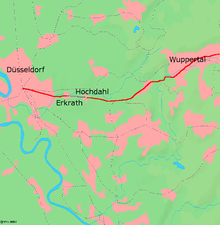

On December 20, 1838, the Düsseldorf-Elberfelder Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft opened the first railway line in western Germany between Düsseldorf and Erkrath . In the further course of the Düsseldorf – Elberfeld railway line, the Erkrath – Hochdahl steep ramp was created between the Erkrath station and the former station and today's Hochdahl stop , where an altitude difference of 82 meters has to be overcome over a distance of almost 2.5 km. There the trains were pulled with a rope until 1926. Until the end of the 20th century, this line remained the steepest main railway line in Europe.

For the 150th anniversary of the railway line in 1988, the new S-Bahn line 8 of the S-Bahn Rhein-Ruhr between Mönchengladbach and Hagen was introduced. Since the timetable change in summer 2009, the S 8 has been partially continued as the S 5 to Dortmund. The S 8 usually runs every 20 minutes, during rush hour it is supplemented by the S 68 between Langenfeld and Wuppertal-Vohwinkel.

| line | Line course |

|---|---|

| S 8 | Hagen - Gevelsberg - Schwelm - Wuppertal - Hochdahl - Düsseldorf - Neuss - Mönchengladbach |

| P 68 | Wuppertal-Vohwinkel - Hochdahl - Düsseldorf - Langenfeld (Rhineland) |

In addition, Hochdahl has a second S-Bahn station at the Hochdahl-Millrath stop, which is located between the Hochdahl and Gruiten stations and is also served by both S-Bahn lines.

Individual evidence

- ↑ data / statistics. Retrieved August 24, 2017 .

- ↑ Wangerin: From Milroyde the new city Hochdahl , 2004, p 9

- ^ Michael Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. mettmann.html. (Online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006).

- ↑ Klockenhoff: Rund um das Neandertal , Verlag Hermann Michael, 1967, p. 43: "Like the majority of the courtyards in the parish of Erkrath, this was also subject to tax in the Unterbach house".

- ↑ City of Erkrath (Ed.): Hochdahl , 1989, p. 105 ff.

- ^ City of Erkrath (Ed.): Hochdahl , 1989, p. 104

- ↑ City of Erkrath (Ed.): Erkrath , 1986, p. 94 ff

- ^ Klockenhoff: Rund um das Neandertal , Verlag Hermann Michael, 1967, p. 45

- ↑ City of Erkrath (Ed.): Hochdahl , 1989, pp. 87 ff.

- ^ City of Erkrath (ed.): Erkrath , 1986, p. 178

- ↑ Hans Seeling: The Hochdahl ironworks 1847–1912 ; in: Niederbergische Contributions - Sources and research on the local history of Niederberg, A.-Henn-Verlag, Wuppertal 1968

- ^ Gerhard Reinhold: Otto bells. Family and company history of the Otto bell foundry dynasty . Self-published, Essen 2019, ISBN 978-3-00-063109-2 , p. 588, here in particular pp. 210, 211, 503 .

- ↑ Gerhard Reinhold: Church bells - Christian world cultural heritage, illustrated using the example of the bell founder Otto, Hemelingen / Bremen . Nijmegen / NL 2019, p. 556, here in particular 198–200, 471 , urn : nbn: nl: ui: 22-2066 / 204770 (dissertation at Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen).

- ↑ City of Erkrath (Ed.): Hochdahl , 1989, p. 117 ff.

- ↑ City of Erkrath (Ed.): Hochdahl, 1989, p. 162 ff.

- ^ City of Erkrath (Ed.): Hochdahl, 1989, p. 199

- ↑ Law on the reorganization of the communities and districts of the reorganization area Mönchengladbach / Düsseldorf / Wuppertal ( Düsseldorf Law ) of 10 September 1974, GV. NW. 1974 p. 890. ( rechts.nrw.de ).

- ^ Federal Statistical Office (ed.): Historical municipality directory for the Federal Republic of Germany. Name, border and key number changes in municipalities, counties and administrative districts from May 27, 1970 to December 31, 1982 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Mainz 1983, ISBN 3-17-003263-1 , p. 293 .

- ↑ City of Erkrath (Ed.): Hochdahl, 1989, p. 112 ff

- ↑ Herbert Bander, Otto Bander, Klaus Beckmann et al., Hochdahl, Meinerzhagener Druck- und Verlagshaus, September 1989, p. 199