Dog years

Dog Years is a novel by Günter Grass published in 1963. It is the third volume of the “ Danzig Trilogy ”, which also includes the novels Die Blechtrommel (1960) and Katz and Maus (1961). Grass' theme in this work is contemporary history of the 20th century, which he tells with burlesque features. For example, the focus is not on Hitler , but on Hitler's dog . With the enumeration of the dog family tree, Grass satirizes the Nazi racial policy . Grass describes changes in the protagonists in a multifaceted way- analogous to the changing historical situation, from the First World War through the period of National Socialism to the post-war period with the beginning economic miracle .

introduction

The focus is on the development of the two main characters Eduard Amsel and Walter Matern due to the political situation in Germany in the first half of the 20th century, especially under National Socialism . Your career is told from the perspective of three different people in three books. The framework forms an order from the entrepreneur Brauxel, Brauksel or Brauchsel, depending on the mood, whose identity with one of the protagonists is already indicated at the beginning and then revealed at the end.

The setting for the first two parts is the city of Gdansk , where Günter Grass was born and grew up. After the First World War, Danzig became a “ Free City ” under the foreign policy administration of Poland through the Treaty of Versailles . When the NSDAP was able to achieve a majority in elections in Danzig in 1933, the demand was made to integrate Danzig into the National Socialist German Reich . Hitler used the problems of international law to fuel the crisis in the German-Polish relationship.

The structure and style of the novel are complex. There are two narrative levels: One is the description of the winter of 1960/61, in which the three fictional narrators write simultaneously on the three commissioned works. These will be “stacked” on February 4th and now result in the commemorative publication for the tenth anniversary of the scarecrow mine, which belongs to the first narrator, Brauxel.

The second level is formed by the narrators' reports, in which they each reproduce a part of the story of Amsel and Matern assigned to them. Grass uses three different narrators with different characteristics as victim (Amsel), witness (Liebenau) and perpetrator (Matern) who represent different views of the German past. But even these assigned roles show breaks and are not clear. He uses different styles of language depending on the fictional narrator.

The first part is written by an artist and mine director in the third person, Brauxel. The sections are subdivided into so-called early shifts. Grass uses an experimental sentence structure with often incomplete sentences:

- “But you can't use a dry stick against the wind. He wants must but wants to throw. Could Senta whistle, get away from here, but not whistle, just crunch - that dulls the wind - and wants to throw. Could Amsel's look with Huh! and huh! from the dyke sole on himself, but his mouth is full of crunches and not full of huh! and Huh! ” (work edition, Volume III, p. 149).

The transitions between the two narrative levels are fluid and often not recognizable at first glance: "... Brauchsel ... leaves a remnant of an eraser between matchstick dikes as ferries on his desk top, which has become the vivid Vistula Delta the morning shift has come in, as the day starts loudly with sparrows, nine-year-old Walter Matern ... opposite the setting sun on the Nickelswalden dike crown; he grinds his teeth. ” (Edition p. 146). In the first section of the sentence, Grass describes how the narrator Brauchsel was sitting at his desk in the winter of 1960; the second part reports from 1926. Most of the chapters of the first book and also some chapters of the two other books begin in a similar form with a brief look at the "now time" (winter 1960/61) and a sudden jump into the narrated story of Matern and Amsel.

In order to create authenticity, Grass uses statements in the Danzig dialect in the first part.

The narrative style in the second book differs significantly from that in the first, because Harry Liebenau describes their childhood together and the lives of the two main characters in love letters to his cousin Tulla. Towards the end of this part there are more and more grotesquely ironic philosophical monologues and descriptions: “The nothing that is tuned by the remote sense works . Nothing is a hole pervaded by television. It is admitted and can be questioned. A black running hole, tuned by the television sense, reveals nothing in its original revelation ” (work edition p. 456).

The third book is written in the present tense throughout. At the same time, the narrator Matern refers entirely to the present and wants to bury his past. “He probably accepted the order (from Brauxel) because of constant financial problems. His defensive attitude is expressed aggressively according to his acting role ... "

content

The first book

The first part of the novel is set between 1917 and 1927. The fictional narrator is Brauxel, although it later turns out that Brauxel and Amsel are the same person who calls themselves differently depending on the time period. This is how Brauxel describes his own childhood in and near Danzig.

Amsel grows up alone with his mother, as his Jewish father died as a German soldier in the First World War. Even as a child he processed everything he experienced by depicting people, fairy tales or the history of Prussia in characters. These are caricatures that he later successfully sold to farmers as scarecrows.

Seven-year-old Matern sees one of these scarecrows and sees himself in it, beating up the blackbird of the same age. Although the two form a very unequal couple, Matern and his dog Senta Amsel accompany you everywhere from now on. At the age of eight they both form a blood brotherhood, which Matern often betrays.

At the age of ten, the two boys switched from the village school to a high school in Gdańsk. While secretly exploring the canals under the school, Matern knocked Amsel down with a club because the latter was trying to take away a human skull they found there to build a scarecrow. On the advice of his old village schoolteacher, Amsel stopped making scarecrows shortly afterwards. Both go to boarding school in Gdansk. During a school trip, they and their class teacher find a baby abandoned by gypsies . School teacher Brunies adopts the child. Since Amsel and Matern spend a lot of time with their teacher, Jenny Brunies grows up with them.

The second book

In this part Harry Liebenau reports in the form of love letters to his cousin Tulla from the point of view of a silent observer of how Matern and Amsel lived from 1922 to 1945, especially under and with the Nazi regime.

Grass lets the narrator play a secondary role as a typical follower among the National Socialists. In the beginning, it's about Liebenau's childhood, which he spends mainly with his cousin Tulla, who is the same age, in a suburb of Gdansk on his father's carpentry yard. Now the novel takes a fantastic turn. When his deaf and mute cousin Konrad drowns, Tulla moves into the kennel of the farm dog Harras, where she lives for seven days. In 1935, the German Shepherd Dog Prince, a descendant of Matern's dog Senta and his puppy Harras, was given to Hitler for his birthday on behalf of the German population of the city of Danzig . This grotesque dog gift causes Harry's father and many acquaintances to join the NSDAP . Harry gets a lot of attention in school through this coup.

After Amsel and Matern passed their Abitur, Amsel started building scarecrows again shortly after the death of his mother. Matern joins the SA at the request of his friend , because Amsel needs uniforms for his characters. But Matern forgets the real reason for joining and feels comfortable in the SA. Although he used to be a communist , he begins to believe in the Nazi ideology. So it happened that in the winter of 1937 he and eight SA comrades beat Blackbird in his garden, knocked out all his teeth and rolled him into a snowman. When the snow thaws, the plump blackbird is transformed into a slim, handsome man who from now on appears as Haseloff.

At the same time, Harry's cousin Tulla forces the fat adopted child of the school teacher Brunies to dance around the Gutenberg monument. After falling down several times, Jenny is also wrapped up as a snowman by Tulla and her friends and turns into a slim, pretty prima ballerina . Amsel fled from Danzig and went to Berlin, where he founded a ballet that later appeared mainly as a front theater in front of soldiers. When Brunies was arrested by the Nazis, a school teacher, Amsel accepted his adopted daughter Jenny into the war ballet.

Before that, however, Matern is expelled from the SA and loses his job at the theater, finally he volunteers for the Wehrmacht . When he was in Gdansk during the attack on Poland , he poisoned Harras, the carpenter's yard dog.

When Hitler visits Danzig, Harry's father is invited to meet him because the dog that was given has now become the “Führer ”'s favorite dog. Harry is beside himself with joy because he is allowed to accompany his father. When Hitler does not appear, the disappointment is not particularly great because from his point of view it was also a great experience.

At the age of 16, Tulla had affairs with soldiers from the front on home leave and was therefore expelled from school. Harry is also leaving school to become an Air Force helper. In his battery unit in Kaisershafen , he spends most of the time hunting rats in the accommodations. The cause of the stench in the area isn't the rats, however, but a mountain of human bones behind the fence of a factory. To win a bet, Tulla gets a human skull and presents it to Harry and u. a. Matern, Harry's instructor. Matern hits her in the face.

When Harry goes on home leave shortly afterwards, Tulla loses the child she longed for through a miscarriage. She then took her first job as a tram conductor.

Despite being injured in the war, Matern had to go to the Eastern Front because he insulted the "Führer" and was later deployed to clear mines. Towards the end of the war he of all people was sent to an English prisoner of war camp for anti-fascists as a former member of the SA . When Jenny is buried in a bomb attack on Berlin and then has to give up dancing, she breaks off contact with Harry. Harry is also relocated several times and finally takes part in the "final battle" for Berlin.

The third book

The third part is subdivided into so-called 'Materniaden' (verballhorn Jeremiade , Köpenickiade ). Matern is a chronicler, who reports on himself at full distance as 'Matern', but sometimes also in first-person form, suppresses his past, reinterprets it, but also admits to some, presents himself as an opponent of the National Socialists but also as an opportunist.

In 1946, at the age of 29, he was released from captivity and met Hitler's dog, Prince. Matern cannot shake him off, gives him the name Pluto and walks with him through ruined Germany. He suppresses his own guilt and takes revenge on former Nazis from his acquaintance by getting their wives or daughters pregnant and infecting them with sexually transmitted diseases. His search for blackbird, which is now active on the black market under the name of Goldmäulchen , remains in vain. From 1949 he worked in West Germany as a caretaker in his father's mill, who predicts the future for future business leaders.

In 1953 he moved to live with friends in Düsseldorf. At around the same time, the Brauxel & Co company is bringing so-called miracle glasses onto the market, with which only 7 to 21-year-old children and adolescents who could not have been guilty of any kind under National Socialism can see the past of their fellow human beings.

Matern gets a job on the radio as a speaker in radio plays for children. He takes a critical look at the entanglements of artists and intellectuals and their turn to the social market economy. He only assumes his own role. The children expose him as the culprit on the radio. His past becomes the subject of a public radio discussion. Matern flees to Berlin and wants to move to the GDR . Before that, he gives the now very old dog Pluto to the station mission. But Pluto chases him and runs after the train with several scarecrows, which miraculously makes him younger. Finally he greets Matern together with Goldmäulchen in the Berlin Zoo station . The three of them go on a pub crawl, and then Amsel sets fire to the pub where Matern told him his story.

At the end of the novel, the two fly their dogs to Hanover and visit Brauxel's mine, where scarecrows are industrially manufactured and sold all over the world. It is only here that it finally becomes clear that Brauxel and Amsel are the same person.

Characterization of the main characters

Characterization of Amsel

Grass composed the novel in such a way that Eduard Amsel guides the reader through his own and Matern's life in the role of Brauxel. Even as a child, Amsel saw through his fellow human beings and expressed this by making scarecrows. He not only achieves a healing effect on Matern, who turns from a bully into an albeit unreliable protector of Amsel, but also has negative effects on other people. Blackbird has to destroy a scarecrow that represents Matern's grandmother wielding a spoon because the maid loses her mind at the sight of her and wanders around "windy and relaxed" (page 65). This figure also has similar effects on animals, especially birds, to which Amsel as the bearer of the name has a very special relationship: For example, when Amsel is baptized, five hundred birds flee from the baptismal society (work edition p. 173), which should show that he has the ability to Driving away birds or causing an uproar is already innate. Thus, according to Grass, he carries his artistic qualities, which he expresses with building scarecrows - that is, driving away birds - right from the start. "The black songbird blackbird is ... the herald of spring" and brings hope that winter is over. Amsel gives his childhood friend Matern this hope of a new beginning after National Socialism and war by first “burning” his own guilt at the end of the book - by setting fire to the pub - and later “sinking” it in the mine.

Amsel survived the Nazi era despite his status as a so-called " half-Jew " only because he ran a front theater for the entertainment of soldiers, i.e. he supported the regime. Grass underlines this dichotomy between victim and perpetrator side by describing Amsel's relationship with birds: on the one hand, as an artist, he is as free as a bird and crosses borders; Panic among the birds (edition p. 178). In trying to process his experiences by building scarecrows, he harms himself by persuading his friend Matern to join the SA in order to get SA uniforms for his scarecrows. Matern and his new comrades attack him because they do not accept his motives, but identify with the National Socialist idea and consider him a “half-Jew”.

His changing names show another characteristic of Eduard Amsel, his enormous adaptability to the respective political conditions. Amsel - Haseloff - Goldmäulchen - Brauxel - each stands for a phase of life. So Amsel is the child and the young adult who lives and experiments very freely. The symbolic animal, the rabbit, in the name Haseloff, on the other hand, stands for fear and ducking away in order to survive in National Socialist society. As a "golden mouth", Amsel manages to exploit the conditions of the black market and continues his parents' business acumen. Brauxel, on the other hand, is characterized by his knowledge glasses and the conversations with Matern as an educator against oblivion. At the same time he is a successful marketer of scarecrows. The dazzling, intangible person with changing identities under different names is a victim, but also an opportunist and a perpetrator at the same time.

Characterization of Materns

Matern, the perpetrator, portrays Grass as a violent figure who hangs her flag to the wind. So he lets him say: “Look at me: bald on the inside too. An empty closet full of uniforms of all sentiments. I was red, wore brown, went in black, changed color: red. Spits at me: (...) ”(work edition p. 662). Even as a child he changed fronts by separating from the group of ruffians and from now on protecting blackbirds. At first he was an enthusiastic communist (red) and was still sticking leaflets in 1936 , but a year later he joined the SA (brown). After the war, he and his father supported the economic bosses (black) and would like to move to the GDR at the end of the book (red).

He tries to suppress his guilt by repeatedly playing different roles, as in the theater, which he later no longer wants to admit, and taking revenge on those whose comrade he was just now. Grass Amsel tries to manipulate Matern and send him to the SA for his own purposes. However, he quickly became a National Socialist and initiated the murderous SA attack on Amsel. In the first scene of the book, Grass hinted at the subject of treason. As a child, he had Matern throw a pocket knife that Amsel gave him into the Vistula. It was the penknife with which the two boys had formed blood brotherhood. At the end of the book, the united person Amsel - Brauxel hides it with great effort from the Vistula and gives it again to Matern, who throws it again into a river, the Spree, thus betraying the friendship for the second time. According to Sabine Moser, the pocket knife symbolizes Matern's guilt towards Amsel, which has survived and is still present in the Vistula over the years, as well as Matern's attempt to overcome it. Other performers, especially Volker Neuhaus, do not see such an admission of guilt and the beginning of Matern's change.

Matern's life is grotesquely shaped by the German Shepherd Dog : His childlike enthusiasm for Hitler is aroused when his father gives the Führer a dog.

Relationship between Matern and Amsel

Grass characterizes the relationship between the main characters as ambivalent. He traces a development that is characterized by breaks and dependencies but also by friendship, hatred, violence and the beginning of reconciliation. First of all, Grass speaks of friendship: So their friendship like "Friendships that were made during or after fights (...) often and breathtakingly prove themselves" (page 46).

To characterize the young Amsel and his friend Matern, Grass introduces Amsel's old alter ego Brauxel, a construction that he reveals to the reader at the end of the novel.

Amsel is gifted, but as a so-called half-Jew, he has a hard time in society and, as a child, is the whipping boy of the village youth. After Matern has joined Amsel, he seems to admire his friend and is his "Paslack", that is, the one who carries the things after him. Only in sport is Matern superior. "This feeling of inferiority (von Matern) turns into hatred in the course of the plot, parallel to the spread of National Socialism ," which announces itself through two important experiences: When Amsel wants to sell a scarecrow to the farmer Lau for the first time, Matern sits on " the dune crest and, according to the noise it made with its teeth, objected to a deal he later called 'haggling' ”(page 53). According to Sabine Moser, this "subliminal aggressiveness, which is noticeable through the grinding of teeth," comes from the fact that, in Matern's opinion, it is humiliating for Amsel to sell his art.

The second incident occurred a few years later when Matern hit Amsel with a club while exploring the canal system, with which he had previously killed the rats of the sewer system. At the same time he insults him as " Itzig " (page 102). Behind this hides the degradation of Jews as "rats" in the National Socialist jargon. By picking up a human skull, Amsel shows for Matern that he “has no respect for ... 'sacred' things”.

Matern cannot get over Amsel's disappearance, although he drove him out himself by initiating the SA attack, and Amsel finally submits in Berlin by saying: “First the interzonal journey with all the trimmings. Then the drinking tour from pub to pub. The air exchange. The joy of reunion. Everyone can't take it (..). Do with me what you want! ”(P. 706). Amsel - Brauxel then leads Matern into his mine to confront him with his past in the form of "scaring off all social systems".

Overall view

All persons in "Dog Years" should be exemplary for their time. Günter Grass said in an interview:

- “All the characters that I have described, no matter how individual they appear, are products of their time, their environment or their social class, e.g. the petty bourgeoisie, or due to their milieu, e.g. B. the school or high school environment. They are of course in literarily emphasized positions, they personify themselves, certain conflicts, conflict situations that are general from the time. "

Grass introduces the misogynist and anti-Jewish work of Otto Weininger's gender and character, published in 1903, into his novel by assigning it very high importance to Amsel's father. Eddi Amsel says:

- “In the year nineteen hundred three a young, precocious man named Otto Weininger wrote a book. This unique book is called Gender and Character , was published in Vienna and Leipzig and, on six hundred pages, tried to deny woman the soul. Because this topic turned out to be topical at the time of emancipation, but especially because the thirteenth chapter of the unique book, under the heading 'Judaism', also denied the Jews, as belonging to a female race, the soul, the new publication reached high, dizzying print runs and ended up in households where otherwise only the Bible was read. ”Albrecht Amsel“ read from Weininger, who, by means of a footnote, considered himself to be part of Judaism: The Jew has no soul. The Jew does not do any sport. The Jew must overcome Judaism in himself ... and Albrecht Amsel overcame by singing in the church choir, by founding the gymnastics club (...) (...). ”(Work edition p. 175).

According to Weininger, Grass Amsel shows traits of a Jew, such as business acumen and a lack of “respect for sacred things”. However, he immediately takes this reference back by attributing Amsel's business acumen to the maternal inheritance. Matern could be the described Aryan with his sporty ambition and camaraderie. “Matern's hatred of blackbird also corresponds to his idealistic outlook. Weininger provides the explanation: 'The Aryan perceives the endeavor to understand and derive everything as a devaluation of the world, because he feels that it is precisely the unsearchable that gives existence its values. The Jew is not afraid of secrets because he nowhere suspects any. '"

Grass shows this when Matern first insulted his friend because of the SA scarers and later beats him up. Little Goldmäulchen tells Matern a story from their two childhoods in fairy tale form as a "commonplace story" (page 687), which can be "found in any German reader (...)" (page 687).

These and the numerous other stereotypical traits Grass assigned them are intended to make the main characters into representatives of many Germans from that time. Matern stands for the so-called common people who gullibly follow Hitler. This also means that Matern's guilt towards Amsel, symbolized by the pocket knife, is the guilt of the German people towards the Jews. His attempts to suppress everything are typical of the post-war period.

Matern's birthday on April 20 corresponds to Hitler's date of birth and thus represents a further connection between him and Hitler. Even after the war, Matern's birthday and thus his at least formal connection to Hitler remains the same in relation to all attempts at denial. Matern's gnashing of teeth, which earned him the nickname “Gnirscher”, expresses his aggressiveness, which is fueled by the Nazi propaganda against Jews and everything non-German and was also expressed in the support of most Germans for the Second World War . The novel was initially to be given the title "The Knirscher".

Amsel not only stands for the victims, but also for the intellectuals, for artists and academics under National Socialism, who recognize that the Nazi ideology is based on untruths, but after a few bad experiences give up the resistance and get through in their own way. They are not doing badly. You support the Nazis half-heartedly, Amsel by participating in the front theater. Real victims of National Socialism appear in the book only as anonymous human bones. (Except for Brunies, who was kidnapped to Stuthof, where he died.)

In this novel, Grass assumes extensive knowledge of German history, religion, philosophy and mythology. For example, he repeatedly uses allusions to the Nibelungen saga , but the content is only sketched out. In addition, events are often briefly indicated, which will only be described in more detail later. Allusions to the tin drum and cat and mouse require knowledge of these parts of the novel trilogy.

Importance of dogs

The title already indicates the great importance that dogs have in this novel on what is happening. The third book begins with the significant sentence: “The dog is in the center.” A few sentences later, Grass continues “Or hold on to the dog, then you will stand in the center”. (Work edition p. 578) The novel is told not only as a story of the relationship between Amsel and Matern, but also as a dog story. "Once upon a time there was a dog who left his master, (...) swam through (...) the Elbe and looked for a new master west of the river". (Work edition p. 575). Dogs and humans are interchangeable; after all, humans are seen in relation to dogs. Characteristics of dogs overlap with real historical and mythological references.

Dogs are often the symbol of human aggressiveness in fables and myths. Dogs are loyal to their master, just as the German people were predominantly loyal to Hitler.

An example of this is Tulla's relationship with the carpenter's dog Harras, whom she incites several times against the artist and piano teacher Felnser-Imbs and the gypsy child Jenny Brunies. Harras is also sent to train after allegedly spoiling him by the half-Jew Amsel, and is thus aggressive towards strangers. This stands for the increasing adoption of Nazi ideology combined with hatred of Jews and Gypsies by the Germans, especially by the German youth.

The repeatedly enumerated pedigree of the dogs, “Senta threw Harras; and Harras begat Prince; und Prinz made history ... ”(for example work edition p. 159, work edition p. 574) refers to part of the National Socialist ideology, according to which many human characteristics depend on the blood of ancestors and only the so-called Aryans are really valuable people on the real relationship of many National Socialists, and especially Hitler's, to purebred German Shepherds.

The names of the dogs also have meaning: Pluto is “the god of the underworld in the Greco-Roman myth of the gods”, where the dog Pluto, symbol of guilt, also watches forever in the mine. Prince, however, stands for the unrestricted rule of Hitler like a king.

After the end of National Socialism, the great escapes of people and dogs begin. "... overflowing dog, hauab dog, without-me-dog, dog throwing (...) deserted dog with the wind in his back; because the wind also wants to go west, like everyone else (...) Everyone wants to forget the mountains of bones and mass graves, the flag holders and party books, the debts and the guilt. "(Edition p. 574)

Dog years are bad years, and Grass describes these bad years in his novel. The book begins with the end of the First World War and the ensuing uncertainty in Europe, with the Great Depression in 1929 and the associated misery of the population, followed by the economic boom under National Socialism and the greatest crime in German history, the Holocaust . Then we talk about the post-war period , when there was initially deprivation and many old party comrades held high positions again, making democratization more difficult.

Enough

Goldmäulchen / Brauxel describes the Germans as "mysterious and filled with God-pleasing forgetfulness". Ironically alluding to the religious image of man in the image of God and the crimes of the Germans, Grass lets Goldmäulchen go on: “One can certainly say that a scarecrow can be developed from every person; after all, we should never forget that the scarecrow will be created in the image of man. But among all peoples who live as a scarecrow arsenal, it is preferably the German people who, even more than the Jewish people, have all it takes to one day give the world the primeval scarecrow. " (Edition p. 798)

At first, Matern reacts with embarrassment, defense and anger. Again he uses the derogatory term Itzig . In the mine, Matern finds “hell”. Alluding to Dante's inferno , Grass writes about the interior of the underground scarecrow factory: “The neighboring circle cannot stop the screaming. (...) The rising and falling howling bulges and stretches every circle. "(Edition p. 812)

In one of the hell chambers, Matern found ironically broken philosophical knowledge in the style of a Heidegger. “The sentence of the Gescheuch. 'Because the nature of scaring is the transcendental springing triple scattering of Gescheuchs in world design.' (...) Hundreds equalized philosophers convert on horizontal salt, greet each other much: 'The scarecrow exists self-grounded his.' " (Factory output S. 821f) . History, economics, everything there is in the upper world is related to scarecrows in the underworld. Hatred and anger rule in the underworld as a reflection of the world.

The ascent from "Hell" initially brings relief. Brauxel is however: The Orkus is up. The end remains vague: the main characters can no longer be distinguished. They can hear each other, are naked, and stay separate. (Work edition p. 834 f.)

The conclusion is interpreted differently in research. Either it is stated that Matern has partially accepted his guilt, a change is brewing, or at the end of the day there is the insight that Matern does not accept the potentially enlightening effect of the scarecrows, which show everything human.

Text variants

"... And in the end, the Bamberg Symphony in their brown work clothes play something from Götterdämmerung. That always fits and haunts as a leitmotif and murder motif through the story that has become pictorial, resurrected in scarecrows and filling the twenty-first chamber in the roof." This is what it says on page 673 of the first edition. However, there are also copies from the first edition (1st – 4th edition from July 1963) to the fourth printing, 17th – 21st edition. Edition from November 1963, in which the word "Bamberger" is blackened, then blackened by hand by the publisher. And if you look at the licensed editions that were subsequently published in various book clubs and as a paperback by Rowohlt, you will find a third variant: "... And at the end a symphony orchestra in brown work clothes plays something from Götterdämmerung." The original text is restored in new editions. The Bamberg Symphony Orchestra were incidentally only founded in 1946 and probably never played in brown divide.

reception

In a television interview in May 1984, Günter Grass described his novel Hundred Years as a more important book than the tin drum . He turns against the "expectations, especially in the criticism that every book ... has now measured against the tin drum ..." The dog years represented a literary risk, also moments of failure, the fragmentary can be found there.

Parts of the literary criticism and also the reader did not share this extremely positive assessment. In contrast to the first two volumes of the trilogy, the book was not a sales success. Most of the reviews have not been gushing. It is regarded as not very exciting, difficult to understand and sometimes template-like. It is composed so complex that the narrative intent of the author is not always clear. A clear demarcation between perpetrators and victims is not sought, rather the line is often blurred. Grass hardly works out the protagonists' individual traits. The narrative flow suffers due to the permanent change of name, level, narrator and perspective as well as nesting. Even Grass' grotesque ideas are not always convincing. In this novel, Grass does not manage to maintain the tension, as in his main work Die Blechtrommel , which initially polarized the public very strongly, but now enjoys unreserved literary recognition.

The Danzig trilogy is often highly valued in Grass monographs, for example by Volker Neuhaus and Ute Brandes, who also rate the novel Dog Years as positive overall.

Neuhaus, editor of the collected works, emphasizes the themes of "forgetting" and "starting over", great escapes from the Russians and from the "mountains of bones", "mass graves", "party books", from "debts" and "guilt". He notes the ambivalence of all the characters, motifs and moral concepts in the novel, works out the references to the tin drum, deals with the meaning of alienated Heidegger quotes and puts the work in a row with the tin drum. "Just as the effect of Oskar's drum went into Die Blechtrommel , so the effect of Amsel's scarecrow book is continued in the book Years of Dogs."

Ute Brandes also discusses the book as part of the Danzig trilogy: “At the end of the dog years , Grass had tamed the demons of his childhood and youth in Danzig by storytelling. The monumental narrative of the Danzig trilogy is full of experienced reality, mannerist distortion and a fantastic pleasure in telling stories. ”With this large three-part work he made the leap into the ranks of international authors.

Others

In this novel, Günter Grass created a literary monument to the Düsseldorf actor Karl Brückel , in memory of his master role as the tailor Wibbel . Incidentally, many Düsseldorfers are unclear why their city, in which Grass lived between 1947 and 1953 and began studying at the art academy , was so viciously reviled in the dog years , for example as "slug-glued plague, this insult to a non-existent god" , as “Mostrichklaks, dried up between Düssel and Rhine” or as “Biedermeier Babel”.

The novel is dedicated to " Walter Henn in memoriam". The director died in March 1963 at the age of only 31 before a film adaptation of Cat and Mouse that was planned with him could be realized.

swell

Footnotes

- ↑ a b c d Volker Neuhaus, Günter Grass. Realities for literature. 2. revised and extended edition. Metzler, Stuttgart 1992, pp. 78-100.

- ^ Sabine Moser, Günter Grass, Novels and Stories, Classic Readings Volume 4, Berlin 2000, pp. 67–73.

- ^ Sabine Moser, Günter Grass, Novels and Stories, Classics Readings Volume 4, Berlin 2000, p. 65.

- ↑ Sabine Moser, Günter Grass, Novels and Stories, Classics Readings Volume 4, Berlin 2000, p. 73.

- ^ Sabine Moser, Günter Grass, Novels and Stories, Classics Readings Volume 4, Berlin 2000, pp. 69 f.

- ↑ a b Ute Brandes, Günter Grass, Heads of the 20th Century, Volume 132, Berlin 1998, p. 37 f.

- ^ Klaus Stallbaum (ed.): Conversations with Günter Grass, quoted in according to Sabine Moser p. 113 f.

- ^ Sabine Moser, Günter Grass, Novels and Stories, Classics Readings Volume 4, Berlin 2000, p. 72 f.

- ^ Otto Weininger: Gender and Character; quoted after: Sabine Moser p. 421.

- ↑ Neil Philip, Mythen visuell, Hildesheim 1999, p. 71 f.

- ↑ Der neue Brockhaus, Lexicon and Dictionary, Volume 4 (Nev-Sid), Wiesbaden 1968, p. 195.

- ^ Günter Grass, Hansjürgen Rosenbauer, Ulrich Wickert: Drummers and snails. A televised talk . In: Günter Grass: Information for readers. Franz Josef Görtz (Ed.), Luchterhand, Darmstadt 1984, p. 33.

- ↑ Deutsches Bühnen-Jahrbuch season 1981/82 in the paragraph about Brückel.

- ↑ Tongue out , cover story / literary criticism of September 4, 1963 in DER SPIEGEL , issue 36/1963 , accessed from the spiegel.de portal on January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Gerda Kaltwasser: Full of grass! , Article from June 2001 in the Rheinische Post (special supplement to Bücherbummel) ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , archived in the Frauen-Kultur-Archiv , accessed on January 12, 2012.

- ^ Walter Henn's last work Die Zeit, No. 14, April 5, 1963.

- ↑ Braking Gurgel and Tongue Out , Der Spiegel, 1963.

expenditure

- Günter Grass: Dog Years . Luchterhand, Neuwied & Berlin 1963. (first edition) (for 13 weeks in 1963 and 1964 at number 1 on the Spiegel bestseller list )

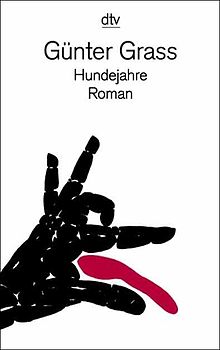

- Günter Grass: Dog Years . dtv, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-423-11823-7 . (dtv, 11823)

- Günter Grass: Dog Years . Steidl, Göttingen 1997, ISBN 3-88243-486-4 . (Work edition, vol. 5)

- Günter Grass: Dog Years . Illustrated anniversary edition. Steidl, Göttingen 2013. ISBN 978-3-86930-666-7 .

- Sabine Moser: Günter Grass. Novels and short stories . Classics Readings Volume 4, Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-503-04960-6 . (Extracts)

literature

- Bernhardt, Rüdiger: Günter Grass: Dog Years. King's Explanations and Materials (Vol. 442). Hollfeld: Bange Verlag 2006. ISBN 978-3-8044-1827-1 .

- Ute Brandes: Günter Grass , Wissenschaftsverlag Volker Spiess, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-89166-979-8 (especially Dog Years, pp. 32–38).

- Sabine Moser, Günter Grass, Novels and Stories, Classics Readings Volume 4, Erich SchmidtVerlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-503-04960-6 .

- Volker Neuhaus: Foreword to the Danzig trilogy ( "In the big and small" ) and afterword to "Dog Years" ( "This manual on building effective scarecrows" ); as well as notes on "Dog Years" . In: Günter Grass: Cat and Mouse. Dog Years , work edition in 10 volumes, Volume III (see above) pp. 838–840, pp. 849–862 and pp. 883–923.

- Volker Neuhaus: Günter Grass . Realities for literature. 2. revised and extended edition. Metzler, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-476-12179-8 (especially Dog Years, pp. 78-100).

Web links

- Exhibition: Found things for Grass readers in the Akademie der Künste Berlin, Oct. - Nov. 2002 (Grass at work on Der Knirscher , published in 1963 under the title Dog Years )