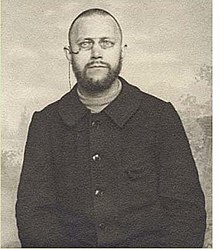

Ivan Aguéli

Ivan Aguéli (born May 24, 1869 in Sala , Sweden , as John Gustaf Agelii ; † October 1, 1917 in L'Hospitalet de Llobregat near Barcelona , Spain ), also known as Sheikh 'Abd al-Hadi Aqhili after his acceptance of Islam , was a Swedish- born wandering Sufi , painter and author. As a follower of Ibn ¡Arab∆ he directed his metaphysical studies towards Islamic esotericism and its similarities with other esoteric traditions of the world. He took René Guénoninto Sufism and founded the Al Akbariyya Society in Paris. As a painter he found a peculiar post-impressionism . His mostly small-format paintings are representational, but by simplifying the forms and using soft, "pale" colors, they create the impression of the remoteness of their objects. Many of them went into the collections of museums.

Childhood and youth

Ivan Aguéli was born in 1869 as the son of a veterinarian in the so-called "silver city" Sala, where the precious metal was mined until 1908. Sala's coat of arms shows crossed mining tools under a crescent moon, both silver-colored, against a blue background. A crescent moon is not just the alchemical symbol for silver; in the Islamic esoteric application of the old symbolism of the star and crescent moon, it also stands for al-Insān al-kāmil , the universal man. Strangely enough, the Sufi concept of the “universal man” as well as its Daoist counterpart, the Chen jen (the “realized man”) should prove to be extremely meaningful in Aguéli's life. In addition, his well-known forerunner and most important stimulus, Emanuel Swedenborg , who came from a wealthy mining family, had studied mineralogical, metallurgical and alchemical studies. For Swedenborg they resulted in a theosophy in the tradition of Jakob Boehme .

From 1879 to 1889 Aguéli conducted his studies in Gotland and Stockholm . In addition to his keen interest in religion and mysticism, he showed an extraordinary artistic talent from an early age. His passion for painting emerges from his saying: "Put me on bread and water, but let me paint!"

In 1889/1890 Aguéli took the Slavic first name Ivan, which corresponds to his old first name John in terms of etymology . Since he initially preferred the Russian spelling, it can be assumed that the change of name was influenced by such Russian writers as Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky and Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev , whose works he studied and admired at the time. According to Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy's research, the hero Ivan of Russian folk tales is synonymous with the mystical knight and first keeper of the Grail Gawain and thus also with Prince Ivan, who after a dangerous search for the water of life penetrates.

Aguéli spent 1890 in Paris , where he became a student of the symbolist painter Émile Bernard , who was close friends with Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin . Here he decided on a French-language adaptation of his surname from Agelii to Aguéli. According to some assumptions, an allusion to "water" also played a role. On his return trip to Sweden, Aguéli made a detour to London , where he met the Russian-born anarchist scholar Pyotr Alexejewitsch Kropotkin . In Stockholm Aguéli was accepted at the art academy. His teachers included the Swedish artists Anders Zorn and Richard Bergh .

Ibn Arabi and the Koran

Research in the Stockholm Royal Library revealed that Aguéli first borrowed a Swedish translation of the Koran on March 11, 1892. He not only began reading Islamic scriptures, including those of the influential Sufi Ibn Arabi , but also showed oriental customs in his demeanor . In a notorious incident at Cafe Du Nord in Stockholm , he asked all of his companions to sit down on the carpet, which the waiters noted with some astonishment.

At the end of 1892 Aguéli went to Paris again, where he was drawn into the political unrest there.

Paris and anarchism

During this period Aguéli was active in various anarchist circles. He was arrested in 1894 for his connections with anarchists like Maximilien Luce and Félix Fénéon . Although acquitted in the well-known "Trial of the 30", he had to spend four months in Mazas prison. He used the detention to study the Koran and oriental languages.

After his release in 1895, Aguéli traveled to Egypt , where he lived until he returned to Paris in 1896. Here he finally converted to Islam between 1898 and 1899 and took the name Abd al-Hadi ("Servant of the Guide").

Sri Lanka

In 1899 Aguéli traveled to Colombo , where he settled in the Malay quarter and enrolled in an Islamic school "to study the influence of Islam on nations outside Arabia". Financial problems forced him to return to Paris in 1900.

Sufism

In 1902 Aguéli traveled to Cairo , where he was one of the first Western Europeans to enroll at the traditional al-Azhar University . At her he studied Arabic and Islamic philosophy. Living in extreme poverty, dressed in Arabic and speaking Arabic better and better, Aguéli soon made numerous Egyptian friends.

By the respected Egyptian Sheikh 'Abd al-Rahman Ilaysh al-Kabir (1840-1921) Aguéli was accepted into the Sufi order al-'Arabiyya Schadhiliyya in 1902 . The Sheikh also awarded him the title of Muqaddim of Europe , which would prove extremely valuable on Aguéli's future trips.

Aguéli was later accepted into the Sufi order Malamatiyya, which explains for some historians his highly unconventional, sometimes bizarre behavior, such as in the Deuil incident mentioned below.

Il Convito

With the blessing of Sheikh Shaykh Ilaysh 'Aguéli founded together with the like-minded Italian journalist Enrico Insabato (1878-1963) the magazine Il Convito (Arabic An-Nadi ), which was published from 1904 to 1913 in Cairo. It was written in Italian to avoid the colonial languages of French and English. The magazine tried to build a bridge between the Christian Europe and the Islamic world. Following the instructions of the Sheikh, Aguéli and Insabato sought to push back French-British influence in the Islamic world in favor of support from Italy. In addition, they promoted the spread of Ibn Arabi Sufism in Europe.

Their greatest success in the promotion of the Italian-Islamic dialogue they achieved in 1906, when the sheikh against British interests, a Cairo mosque dedicated to the memory of the Italian king Umberto I. inaugurated.

Finally, the magazine, increasingly branded as "anti-colonial", was banned and closed by the British colonial administration in 1913.

World War I and Spain

Aguéli's rejection of British colonial administration was so evident that the Consul General expelled him to Spain in 1916 on the grounds that he was a spy for the Ottoman Empire. Stranded there, Aguéli lacked the financial means to return to Sweden.

Aguéli sent numerous letters to Sweden asking for financial support. However, because of his conversion to Islam and persistent poverty, most of his friends had already turned away from him; there was no help. Finally, on October 3, 1917, a check for 1,000 Spanish pesetas, made out by his friend and mentor Prinz Eugen , arrived at the Swedish consulate, but this help came too late. In the early morning hours of October 1, the 48-year-old Swedish wandering Sufi in L'Hospitalet de Llobregat was hit and killed by a train while crossing the railroad tracks.

The prince arranged for the check to be handed over to Aguéli's impoverished mother, who had sacrificed all her savings to support her son. He also instructed the Swedish Foreign Minister to secure and bring back all of the victim's belongings.

In 1920 almost 200 paintings by Aguéli selected from this estate were exhibited in Eugen's Stockholm Villa Waldemarsudde . The remaining works were sold to impressed art lovers.

Aguéli, René Guénon and Al Akbariyya

Aguéli's friendship with René Guénon , who was then the editor of the Paris esoteric magazine La Gnose , began in 1910. Auguéli had aroused Guénon's interest in Islam through numerous articles on metaphysics, Sufism and Daoism. As Moqaddim of the Schadhiliyya order and European Commissioner of Sheikh Ilaysh Aguéli founded the secret Sufi society Al Akbariyya; here he inaugurated Guénon in 1912.

As is widely believed, Al Akbariyya's existence and effectiveness were kept top secret. Until 1930, when he - like Aguéli before him - traveled to Cairo, Guénon did not appear publicly as a Muslim.

It is also worth noting that Guénon in his book Orient et Occident from 1924 deals extensively with the metaphysical relationship between Daoism and Sufism, which Aguéli touched on in an article for La Gnose as early as 1911 under the heading "Pages, dedicated to Mercury". This article is one of Aguéli's most famous works. Some other students also took up Aguéli's suggestions, for example Toshihiko Izutsu with Sufism and Taoism from 1984.

Aguéli and Swedenborg

Aguéli was introduced to the teachings of the 18th century mystic Emanuel Swedenborg as a teenager. Swedenborg's metaphysics and unitarianism came close to the Christian concept of divinity. They made a lasting impression on Aguéli and contributed to his conversion to Islam.

The similarities between Sufism and Swedenborg's metaphysics, first discovered by Aguéli, were discussed in detail by Henry Corbin in his 1995 book Swedenborg and Esoteric Islam , published in 1995 .

Aguéli as an activist: animal welfare, feminism

As the son of a veterinarian, Aguéli loved animals and also publicly advocated their rights. A notorious incident occurred in 1900 not far from a bullring in the Paris suburb of Deuil : Aguéli shot a Spanish matador . He justified his attack in court and refused to apologize. Because of the support from the French animal rights movement, he got away with a suspended sentence. In the course of his life, Aguéli developed a close friendship with the eccentric French poet and animal rights activist Marie Huot (1846–1930).

Aguéli was also open to the question of women's rights. In a letter to Huot he even stated that because of the existence of female Sufi saints, Ibn ¡Arab∆ and Sufism must be regarded as profeminist. In another letter he called the Swedish playwright August Strindberg an “idiot” because he claims that women are inferior to men.

Aguéli and art

In 1912, while Aguéli lived in Paris, he began writing articles on contemporary art and art theory. One of his most extraordinary texts is an article that deals with Pablo Picasso and Cubism . It aroused the interest of the prominent Parisian poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire , who tried in vain to win Aguéli for a series of jointly developed texts on art issues. Aguéli later tried to enable his mentor Prinz Eugen to meet Picasso and Matisse .

Aguéli's legacy

In Sweden Aguéli is counted among the outstanding representatives of contemporary painting. Many of his paintings can be found in the Swedish National Museum , Stockholm, the Museum of Modern Art , New York and the Aguélimuseet, Sala. Its importance was underlined in 1969 when the Swedish Post issued six postage stamps showing Aguéli's paintings on the occasion of Aguéli's 100th birthday.

Aguéli's remains were transferred from Barcelona to Sala in 1981, where they were buried not far from the Kristina Church according to Islamic rites. Sala also houses the Aguéli Museum with the largest collection of Aguéli's works of art. In Sala, a square, a monument, a park and a street are named after Aguéli.

Under the patronage of the Swedish King Carl XVI. Gustaf was shown another exhibition in the Stockholm Villa Waldemarsudde in 2006 , which this time honored both Aguéli's art and his Muslim heritage.

Sufis had given Aguéli the title Abd al-Hadi “Noor-u-Shimaal” (“Light of the North”) after his death in order to recognize that he was the first official Sufi to bring Sufism to Western Europe and Scandinavia. Although it cannot be said that Aguéli was a perennialist or a traditionalist, his ideas established a certain original traditionalism that was later worked out and established by Guénon and Schuon. In Sweden, the apprenticeship of René Guénon and Frithjof Schuon found pupils like Kurt Almqvist and Tage Lindbom .

literature

Swedish:

- Kurt Almqvist : I tjänst hos det enda - ur René Guénons Verk. Nature and culture, 1977.

- Kurt Almqvist: Ordet är dig nra. Om uppenbarelsen i hjärtat och i religionerna. Delsbo, 1994.

- Hans-Erik Brummer (Ed.): Ivan Aguéli. Stockholm, 2006.

- Gunnar Ekelöf : Ivan Aguéli. 1944.

- Axel Gauffin: Ivan Aguéli - Människan, mystikern, målaren. I – II, Sveriges Allmänna Konstförening's publication, 1940–41.

- Viveka Wessel: Ivan Aguéli - Portrait av en rymd. 1988.

English:

- Paul Chacornac: The Simple Life of Réne Guénon. Sophia Perennis, pp. 31–37 (incorrect, as the author relies primarily on secondary sources)

- Meir Hatina: Where East Meets West: Sufism as a Lever for Cultural Rapprochement. In: International Journal of Middle East Studies. Volume 39, Cambridge University Press, 2007, pp. 389-409.

- Seyyed Hossein Nasr: Sufism: Love and Wisdom. World Wisdom Books, 2006, p. X of the foreword.

- Jade Turner, (ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Art. Grove, 1996, pp. 465-466.

- Robin Waterfield: Réne Guénon and the Future of the West. Sophia Perennis, pp. 28-30.

French:

- Abdul-Hâdi (John Gustav Agelii, dit Ivan Aguéli): Écrits pour La Gnose, comprenant la traduction de l'arabe du Traité de l'Unité. Archè, 1988.

further reading

- Ananda K. Coomaraswamy : Symplegades. In: Martin Lings , Clinton Minnaar: The Underlying Religion: An Introduction to the Perennial Philosophy. World Wisdom Books, 2007, pp. 176-199.

- William Ralston Shedden-Ralston : Russian Folk-Tales. New York, 1873.

Individual evidence

- ^ Waterfield, p. 29

- ↑ Gauffin, p. 38

- ^ Coomaraswamy, p. 195, footnote 31

- ↑ Ralston, pp. 235 ff

- ↑ Gauffin I, p. 67

- ↑ Gauffin I, p. 73

- ↑ Gauffin I, p. 75

- ↑ Gauffin I, p. 180

- ^ Gauffin I, p. 131

- ↑ Gauffin II, p. 44

- ↑ Gauffin II, p. 42

- ↑ Gauffin II, p. 121

- ↑ Almqvist, pp. 17-19

- ↑ Gauffin II, p. 143

- ↑ See article in Hatina, pp. 389–409

- ↑ Gauffin II, pp. 191-192

- ↑ Brummer, pp. 63-64

- ↑ Brummer, pp. 67-73

- ↑ Almqvist, p. 19

- ↑ Almqvist, pp. 17-19

- ↑ Waterfield p. 30. For the article itself see Écrits pour La Gnose .

- ↑ Gauffin I, p. 30

- ↑ Gauffin II, pp. 93-98

- ↑ Gauffin, pp. 218-219

- ↑ Brummer, pp. 124-125

- ^ Brummer, p. 125

- ↑ Illustration of the postage stamps

Web links

- Ivan Aguéli (biography on the pages of the Aguéli Museum in Sala; Swedish)

- Painting by Ivan Aguéli in the Prince Eugen Waldemarsudde art collection (Swedish)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Aguéli, Ivan |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Agelii, John Gustaf (maiden name); Aqhili, Sheikh 'Abd al-Hadi (Islamic) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Swedish painter, author and Sufi |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 24, 1869 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Sala , Sweden |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 1, 1917 |

| Place of death | L'Hospitalet de Llobregat , Spain |