Childlessness

Of childlessness in the context of family policy and population policy discussions then speaking, if a partnership, in particular, marital married couple as statistical entirety conspicuously few (see. Birth deficit or if many individuals have) no children. For 2017, the average number of children per woman for Austria and Switzerland was 1.52, and for Germany 1.57 with childlessness in 2017 for women born in 1967, former federal territory (D) of: 22.0%, new Federal states: 10.5%, and for Germany as a whole: 20.8% proportion of childless women among all women born in 1967.

One finds childless in the phase before potential parenthood, living together without children in the household occurs in the phase after the last child has moved out of the parental household and there are also permanent childless. A distinction must be made between those who are still childless , parents without children in the household and those who are permanently or lifelong childless . A distinction must also be made between people who have not conceived or given birth to a child ( biologically childless ) and people who have never raised an underage child ( socially childless ).

In the case of involuntary childlessness, there is also talk of an unfulfilled desire to have children .

Sociological classification

There is no uniform definition in the sociological and psychological specialist literature. After Nave-Herz and Schneewind, there is a group that remains childless for medical reasons, regardless of whether the cause is organic or psychosomatic, a second group are couples who consciously decide not to have children, while a third group despite the desire to have children has no children yet. In this group, Schneewind also combines couples who in principle decide to have a child, but who postpone conception until biological limits arise.

Christine Carl distinguishes three types of women who remain childless for life:

- Early decision-makers ( "early articulators"): This group decides against children very early (to mid-20) and also alone, not within a partnership

- Late decision-makers: This group makes the decision against children in partnership and at a later point in time (from mid-30s), ie “before the biological clock runs out”. While the early decision-makers do not articulate a natural desire to have children, for this group the desire to have children is a matter of course.

- Aufschieberinnen ( "postponers"): The last group does not make any explicit decision to live without children, d. H. they "ultimately remain childless for external reasons (operations, medical reasons or menopause)." This group either missed the "right time" or did not find a suitable father.

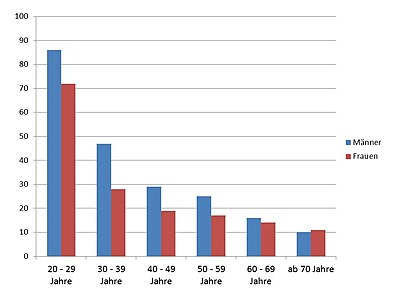

Men postpone parenting longer than women on average. In addition, in surveys a higher proportion of men than women indicated that they were childless. The cohort sequence shows an increasingly clear postponement of starting a family and an increasing prevalence of permanent childlessness. Among women, with a higher level of education, there is a higher proportion of childless people, whereas the highest proportion of childless men is found in the group of people with low educational qualifications.

According to a milieu study by the federal government, the middle and upper classes are particularly affected by childlessness. These include v. a. Citizens who value careers and individuality. Sections of the population that are more conservative or hedonistic, belong to the middle-class or disadvantaged milieus are less likely to be involuntarily childless.

Situation in Germany

Statistical surveys

The childlessness of men is generally not recorded statistically. Even with the microcensus, men are not asked whether they have had children and how many.

| Cohort birth cohorts |

west |

east |

Ges. |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1895-1904 | 33% | ||||||||

| 1900-1909 | 20% | ||||||||

| 1901-1905 | 26% | ||||||||

| 1905-1909 | 33% | ||||||||

| 1910-1914 | 28% | ||||||||

| 1910-1919 | 19% | ||||||||

| 1915-1919 | 25% | ||||||||

| 1919-1921 | 17% | ||||||||

| 1920-1924 | 25% | 16% | 23% | ||||||

| 1925-1929 | 25% | 18% | 23% | ||||||

| 1930-1934 | 22% | 18% | 11% | ||||||

| 1934-1935 | 16% | ||||||||

| 1935-1939 | 18% | 12% | 13% | ||||||

| 1937-1938 | 15% | ||||||||

| 1939-1940 | 10% | ||||||||

| 1940-1944 | 13% | 16% | 12% | ||||||

| 1946-1947 | 16% | ||||||||

| 1950-1954 | 17% | 14% | 14% | 23% | 16% | ||||

| 1951-1952 | 22% | 10% | |||||||

| 1955-1959 | 19% | 17% | 18% | ||||||

| 1957-1958 | 24% | 8th % | |||||||

| 1960-1964 | 21% | ||||||||

| 1961–1962 | 25% | 10% | |||||||

| 1965-1966 | 26% | 14% |

The birth statistics as official statistics are not sufficient to estimate actual childlessness, since the order of births for births before 2008 is only recorded for existing marriages. Children born outside of marriages did not appear in the statistics until 2008. Since there are no official data on childlessness in Germany, estimates of the microcensus and the socio-economic panel must be used.

From the report of the Federal Statistical Office published in 2011 entitled How do children live in Germany? it emerges that in no other country of the European Union live so few children as in the Federal Republic; only 16.5% of the more than 81 million German citizens are younger than 18 years.

Microcensus

Most of the cited data on the extent of childlessness in Germany are based on the microcensus. The microcensus is a representative survey of the state statistical offices on the economic and social situation of the population. A total of 1% of all households in Germany are surveyed, i. H. around 370,000 households, in which around 820,000 people live.

Until 2007

Up until 2007, the microcensus did not ask about the children born to a woman, but only about the number of unmarried underage children living in the household. No distinction is made between biological children, stepchildren, adoptive children and foster children. According to the definition of the microcensus, the following women are considered childless:

- Women who (yet) have no children;

- Women whose children have already left their parents' household;

- Women whose children do not live in the maternal household;

- Women whose children still live in the household but who are no longer single;

- Women whose children still live in the household but who are of legal age.

Only women who do not (yet) have children (case 1) are truly childless.

The resulting data was described by Kreyenfeld, an expert at the Max Planck Institute for Demography in Rostock, as "uniquely unreliable in a European comparison".

Since 2008

| Old woman |

D. | west | east |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40-44 | 21% | ||

| 50-54 | 16% | ||

| 60-64 | 12% | ||

| 40-75 | 16% | 8th % | |

| 35-39 | 28% | 16% |

In 2008, the question of the children born was raised for the first time in the microcensus. In future, it will be asked regularly every four years for all women between the ages of 15 and 75.

The 2008 microcensus produced the following results:

- Overall, 21% of women aged 40 to 44 were childless in 2008, while the proportion among women aged 50 to 54 was 16%. Among women aged 60 to 64, 12% had not given birth to children.

- There are significantly fewer childless women in eastern Germany than in the west. Among the 40 to 75 year olds in the west, 16% have no children, in the east the figure is 8%. Among the 35 to 39 year olds in the west 28% have no offspring, in the east only 16%.

- In West Germany there is a connection between level of education and childlessness. 26% of women with a high level of education have no children, those with a medium level of education make up 16% and among women with a low level of education 11%.

- Among the West German female academics between the ages of 40 and 75, 28% have no children, while only 11% of the East Germans with academic degrees.

- Of all 25- to 39-year-old women, 83% of the wives were also mothers in 2008. Among the divorced, separated or widowed women, the proportion of mothers was 79%. Of the unmarried women living in a civil partnership, 36% were mothers. 15% of single women have given birth to children.

- Women with a migration background are less likely to be childless than women born in Germany. 13% of the 35- to 44-year-old immigrant women have no children, compared to 25% of those born in Germany. Among the 25 to 34-year-olds, 39% of women with a migration background have so far no children, compared with 61% of women without.

The 2012 microcensus confirms the trend towards an increase in the proportion of permanently childless women from birth year to year of birth in Germany. The rate of childless women has not fallen below 20% since 1964. A trend towards a significant increase in the proportion of childless women can be seen among the less qualified in the west and the highly qualified in the east.

Surveys from registry offices

Since January 2008, the registry offices have recorded the biological ranking of the births of all mothers, as well as the age of all mothers when their child was born.

Until 2007, registry offices only collected and passed on data on children born to a woman during an existing marriage; the child count started from zero at every wedding; the number of children in the statistics was based on the “ranking of the births in the existing marriage”.

Childless as payer of taxes and duties and as non-recipients of transfer payments

Income tax and child benefit

The child tax allowance and child care costs can only be claimed from income tax by persons who are “ parents ” to a child .

Biological children and adopted children are taken into account (i.e. children with whom the taxpayer is related in the first degree ). Foster children are taken into account if the child is accommodated in the taxpayer's household and there is a permanent family-like relationship with this child. This is the case, for example, in the case of admission as a foster child within the framework of assistance in bringing up full-time care ( Section 27 , Section 33 of Book VIII of the Social Code ) or within the framework of integration assistance ( Section 35a, Paragraph 1, Sentence 2, No. 3 of Book VIII of the Social Code). The guardianship relationship must not be limited in time from the outset. Admission with the aim of adoption always leads to consideration as a foster child. There must be no custody or foster relationship with the biological parents of the foster children. This means that the family bond has been permanently abandoned. Occasional visits do not prevent this.

Children of legal age are only considered "children" for tax purposes if they have not yet reached the age of 25 and are in training. Unemployed children can be considered up to the age of 21. The age limits can shift further due to military / community service. The inclusion of children of legal age up to and including the 2012 tax year required that they did not exceed a certain annual income. Regardless of age, children are taken into account if they are unable to support themselves due to a disability.

Those to whom the above provisions do not apply are considered “childless” under German income tax law. In this sense, “childless” are also not entitled to receive child benefit ( Section 32 EStG ).

care insurance

Since January 1, 2005, childless members of the statutory long-term care insurance have to pay 1.95% instead of 1.7% of their income subject to social security contributions to their insurance company. The background to this new regulation is a judgment of the Federal Constitutional Court of April 3, 2001, through which the legislature was given the mandate to make a regulation that takes child-rearing benefits into account when determining the contribution to social long-term care insurance. The rule does not apply to people born before January 1, 1940, those doing military or community service and those receiving unemployment benefits .

All persons over the age of 23 who cannot prove that they are “parents” are considered to be “childless” within the meaning of the regulation. The biological parents, adoptive parents as well as step-parents and foster parents are considered parents. If there is a child, both parents do not have to pay the premium in the long term. This also applies if the children are already adults or a child is no longer alive.

Pension insurance

Following on from the constitutional court ruling on long-term care insurance, a discussion began in 2001 on the question of whether childless people should not be drawn on more to finance pension insurance or whether their pension should be reduced. Hans Werner Sinn's justification for corresponding considerations:

“Before Bismarck introduced pension insurance, it was clear to everyone that without children of his own he would be poor and that he would have to rely on the alms of his relatives. Having children was therefore part of normal life planning, as is still the case today in most countries on earth. Pension insurance has broken the link between the standard of living in old age and the number of children they have. [...] Nobody thinks about retirement anymore when planning children. This proves how strong the fertility inhibition is exercised by the state pension insurance. "

In 2003 a proposal was made to halve the childless pension.

In 2004, the CSU developed plans according to which childless people should pay up to 70 € per month more than those with children insured persons into the statutory pension insurance.

So far, all of the relevant considerations have not been able to win a majority.

Methodological problems

Forecast of the number of permanently childless

In order to answer the question of whether young adults, who usually have no children yet, remain childless in the long term, it is necessary to make prognoses. As a rule, you will be asked for the number of children you want. According to a survey carried out by “Perspektive Deutschland” in 2003 and 2004, half of women aged 20 to 34 want two children, 19% want a child and only 14% do not want any children at all. From a purely statistical point of view, every woman at this age would like to have 1.8 children. Men, on the other hand, want fewer children, namely only 1.59. In fact, for some time now, only fewer than 1.4 children per woman have been born on average in Germany. This difference limits the validity of the forecasts.

The 2006 Shell study looked at the desire for children among young people. In 2006, 62% of young people wanted children. This is less than in 2002. Desire for children has decreased in all classes - except in the upper middle class. They have decreased most among young people from the lower class. Of these, only 51% want children. In the lower middle class it is 59%, 61% in the middle class. Desires for children are most common in the upper middle class, with 70% wanting their own children. Finally, 62% of young people from the upper class want children.

Assignment problems

Phased educator role

In the context of modern patchwork families the term childless complicated to handle: men and women who temporarily help to care for children of their "stage of life companions or -gefährten" but do not have children and never a formal guardianship have acquired, are conceptually difficult to classify.

Unknown and unrecognized paternity

As a rule, anonymous sperm donors are considered to be “biologically childless” (unless they have also become fathers by conventional means) until their identity is revealed. Because in many cases the real biological father of a child is unknown to most of those affected (see also Kuckuckskind ), the number of biologically childless men is likely to be generally overestimated.

Bogus fatherhoods

In cases in which the biological mother of a child was not married, an official guardian decided by 1998 whether the man whom the mother claimed to be the father of the child should be regarded as the “father” and receive his rights and obligations. In 1998 the child law was changed in such a way that the father is the one who acknowledges his paternity and whom the child mother recognizes as the father.

After the change in the law, there were cases of “social abuse” in the form of “bogus fatherhoods”: a man recognized several hundred children in the Third World as his own children and thus acquired a claim against the German state for help with those due become alimony for "his" children. In other cases, women whose children were allegedly fathered by Germans or men who allegedly had children of German women were able to derive a residence permit for Germany from this.

In 2006, a “law supplementing the right to challenge paternity” was passed, which enables public authorities to challenge paternity.

Causes of Childlessness

Social causes

In its edition of January 12, 2005, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung summarized the results of a Forsa survey of 40,000 men and women between the ages of 18 and 49 about the reasons for so-called deliberate childlessness as follows:

“The lack of a suitable partner, the satisfaction with a life without children, higher living costs and worry about the job are the most important reasons why more and more women and men in Germany are deciding against starting a family. A lack of childcare facilities, on the other hand, only plays a subordinate role in the decision to live without children. "

According to a study by the Foundation for Future Issues in July 2013, the main reasons for childlessness were mainly the financial costs for the next generation, the fear of losing their own freedom, and the fear of a career breakdown. A lack of state requirements, such as the lack of childcare, also played a role for almost every second respondent. A 2016 study of the reasons for childlessness showed that not much has changed even three years later. For 63% of those surveyed, the financial burden is too high according to their own statement. 61% do not want to lose their independence and 55% consider their own career to be more important than starting a family. In addition, for 51% of those surveyed, family and work are still not compatible today.

The thesis, according to which people who are not impaired in their fertility, should be regarded as "intentionally childless", is questionable. According to a survey published in June 2007 by the “Institut für Demoskopie Allensbach”, only 8% of 25-59 year olds in Germany do not want or want a child. However, the reference quantity also includes fathers and mothers as well as people whose desire to have children was not fulfilled and people who only want to realize their desire to have children later.

Changed gender relations and living conditions

Fewer and fewer people go through their lives in forms that used to be considered a “normal biography”: Marriage in their mid-20s, children are born relatively quickly, the man is the “main breadwinner” throughout the marriage, while the woman at most “earns something” (but herself in full-time employment not as much as the man); in short: in most cases, biographies resulted in a housewife marriage with several children.

Much has changed in these conditions:

- Increased consumption desires: Over time, consumption desires have increased in rich countries. Even couples with middle and low incomes can now afford expensive vacations and visits to restaurants - if they do without children. While general prosperity has increased in most countries, so have demands.

- Increased costs of training: In many countries you have to have studied to get a good job. Even parents who have never attended university themselves often see it as their duty to keep this path open for their children. In countries with an underfunded public school system, many couples see it as their parental responsibility to finance a private school for their children. Parents limit the number of their children in order to give them the best possible starting opportunities, and they postpone starting a family in order to build a financial cushion. Often, however, they wait too long and notice that the woman's fertility has already decreased by the time they are finally ready to start a family.

- Many people have great problems even finding a partner. In 2006 dating sites took in € 65.6 million. In Germany, 8.94 million people between the ages of 25 and 65 live in one-person households. Only 32% of women and 27% of men name “the need for independence” as the main reason for being single; the remaining respondents are more or less involuntarily singles. This is the result of increasing individualization tendencies.

- Even if you have found a partner, that does not always mean that the mother or father concerned wants or can become children together. Most of the time, the men take on the “brakes” role.

- Since the first sexual contact, most people have gotten into the habit of “turning the traffic light to red”; H. To perceive non-fertility as a normal case. The question of whether and when “the traffic light should be switched to green” is often suppressed, while before the introduction of effective contraceptives there was always a risk of pregnancy as a result of sexual intercourse, i.e. children were born “just like that” (without conscious Family planning ). The overwhelming acceptance of the birth control pill since its appearance in the 1960s shows that large sections of the population wanted to control and reduce the number of children.

- More flexible employment, professional careers or consumer-oriented lifestyles have increasingly replaced traditional family ideas since the 1960s. The guiding principle of success and career often conveyed through advertising and the media could play a role here.

- The later career entry also plays a role. The point in time at which a pregnancy can still be initiated without any problems is often missed.

- The high number of abortions that have now largely been legalized is likely to be a not inconsiderable factor in the negative demographic balance. The number of abortions in Germany between 1974 and 2005 is estimated at 4.4 million to 8.8 million.

- In the past, a marriage lasted a lifetime out of economic necessity , but the importance of marriage has declined sharply. The change of partner has become a reality. Women can no longer rely on lifelong financial security if, as a housewife, they focus on raising children in their lives. With the possibility of a divorce in the back of their minds, they are often willing to create their own means of subsistence for a living.

- Long-term maintenance obligations and costs for children, possibly also for the woman in the event of separation, but legal disadvantages as a father, even if the separation was unilateral from the woman, are among the most weighty fears that suppress a desire for children in men . Refusal or postponement of the desire to have children among men is also known as a procreation strike , with women it is referred to as a birthing strike .

- Having children is perceived by fewer and fewer people as a necessary prerequisite for "happiness in life". According to a survey carried out by the “Institute for Demoskopie Allensbach” in 2003 with the title “Factors influencing the birth rate. Results of a representative survey of the 18 to 44 year old population “only 47% of the childless consider a family to be an indispensable requirement for happiness in life, while 71% of people with children agree with this statement.

- The lively debate about the Regretting motherhood study in 2015 shows that, before giving birth, many women had illusions about the extent of “motherhood” that would follow after the birth. The corresponding “disillusioning” reporting could have a deterrent effect on women who primarily hope that children will increase their individual happiness in life.

Difficult to combine family and work

The dependence of the desire to have children on the compatibility of family and work is of paramount importance in Germany in an international comparison. A longer phase of postadolescence , which leads to a later and later entry into economic independence and family obligations due to longer training periods, as well as the low acceptance of working parents by companies in Germany often prevent early parenthood. To what extent the decision against a child deserves to be called "voluntarily" is controversial. West German women in particular, who were shaped by the family policy of the old FRG, are often faced with the problem of having to choose either a child or a career. A team led by Prof. Hans Bertram expresses itself on this complex in a report that was issued on behalf of the “Federal Ministry for Family, Seniors, Women and Youth”.

Arguments such as the employer's family-friendly conditions and childcare options play a central role. Inadequate childcare in Germany, especially in the old federal states, is seen as another reason for childlessness. So far there has been no need-covering offer for children under three years of age and for schoolchildren in West Germany. This leads to the difficulty of finding a full-time care place for children, so that full-time employment for both parents, as is common in Denmark, for example, is difficult or impossible for them. This also leads to a loss of income that puts families in a financially worse position than singles.

The legitimate concern in part, for a family foundation and subsequent "baby break" no more way back into the profession , reflected in the high number of undecided, childless men and women resist.

Childlessness depends, among other things, on the working conditions of the industry in which potential parents work. In Germany, for example, women in the media sector and in higher management are particularly often childless - in areas that demand professional mobility and flexibility in terms of time. Furthermore, 47% of women working in the arts, 41% of women working in the humanities and natural sciences and 40% of women working in the field of “journalism, translation and libraries” are childless. Although the general rule applies that women are more likely to remain childless the more educated they are, this does not apply equally to all professions. Only 27% of female teachers remain childless, which means they are closer to the average childlessness value than other academic professions. Finally, there are also professional groups in which childlessness is an extreme exception. In the case of female sales staff and cooks, only 15% of women are childless and only 7% of female cleaning and waste disposal workers do not have a child of their own.

In Sweden, for example, female hotel and restaurant workers are more likely to be childless than female teachers and doctors. The problem of another industry related to childlessness is discussed below ( # Religious considerations ).

Financial burden and social status

Another reason given by some is that the financial burdens caused by children in Germany are shifted unilaterally on families and mothers with children and that children are a private luxury pleasure. Indeed, it is undisputed that children are expensive. The Federal Constitutional Court has already warned in a decision that families with children in Germany are disproportionately burdened by social benefits in relation to those without children, without their contribution to the future maintenance of the social system (“ intergenerational contract ”) being adequately taken into account when collecting contributions. This fact is also rated as “transfer exploitation of families”. To remedy this, the Federal Constitutional Court has given the legislature the mandate to further relieve families with children. Whether this has been done to a sufficient extent is controversial, since on the one hand funding is associated with high costs and the funds for this are therefore very difficult to find and, on the other hand, opinions about the type of funding differ widely.

, Is questionable how many people actually mainly why not have children, because they believe that to this "luxury" to can not afford or want. Such people approach the decision for or against children as Homo oeconomicus , who constantly makes economic cost-benefit calculations and makes his decision dependent on it alone. It ignores the fact that the joy that children bring to their parents is an immaterial benefit that has to be “offset” if they experience this joy .

In addition to the approach more child benefit = more children, there is the thesis that child benefit should only be the very last aspect of the support packages for families, because the postulated effect would otherwise not take effect or only take effect temporarily. In West Germany, mothers who have their children looked after in day nurseries and kindergartens are sometimes still considered poorer mothers, although educational science opposes this. In addition, there is a shortage of accommodation options for these institutions in West Germany. The second child is often born in the East from the experience that this care worked so well for the first. Nevertheless, the fertility rate in eastern Germany is lower than in western Germany.

Having children does not increase social prestige in Germany: women and men who have successfully raised two or three children hardly have a higher reputation in Germany than childless people with the same job.

Thoughts about the future

afraid of the future

In a study by the Robert Bosch Foundation, 50% of the childless gave reasons against having children: "I am too worried about the future my children would expect". The thesis is often put forward that future prospects are being assessed more and more pessimistically . In particular, the consequences of globalization should also be counted, which supposedly had a noticeably negative effect on Germany. Increasingly, especially among academics, temporary and thus insecure working relationships are a decisive obstacle to the realization of a life planning with the fulfillment of the desire for children.

Above all, young, educated people punished society , which no longer gave them security. They therefore refused the offspring. While the sentence “I don't want to put children in this world” in the 1980s mainly referred to the then global fears of nuclear threats and environmental destruction, today there has been a reluctance to have a society that is one-sidedly oriented towards individual prosperity. The persistently high unemployment and mistrust in the underlying economic system is another factor in a negative assessment of the future prospects for yourself and your own offspring, in addition to the fear of an increasing threat to the individual's existence in the context of globalization.

Conversely, some economists see a reason for the widespread childlessness in the lack of fear of the future: Anyone who enjoys "fully comprehensive insurance" in the form of high pension payments in old age, although (or precisely because) they have no children of their own, does not feel that The fight against poverty in old age requires personal commitment that goes beyond paying pension insurance contributions.

Striving to improve life on earth

Many people also remain childless because they see a contribution to the improvement of life on earth in consciously renouncing their own children. In particular, overpopulation , which presumably overstrains the earth's carrying capacity , is at the center of relevant considerations. This has negative consequences, namely:

- Environmental degradation ,

- political, economic, social tensions,

- Lack of food .

In view of these prospects, the VHEMT movement advocates, for example, that people critically deal with any desire to have children, in order to then voluntarily forego their own reproduction based on their own insight.

Religious Considerations

For a small minority who feel called to renounce sexuality and start a family, such as religious or Roman Catholic priests , religious considerations also represent a reason for wanting childlessness. In Christianity , such considerations are also biblically included ( 1 Cor 7.1 and 8 EU ) justified.

Unwanted childlessness

Many people are involuntarily childless for medical reasons. Unwanted childlessness is a condition characterized by suffering from infertility (also known as infertility or sterility). In 1967, unwanted childlessness (inability to conceive and / or conceive) was recognized as a disease by the WHO Scientific Group on the Epidemiology of Infertility . According to the WHO definition, infertility / sterility is to be diagnosed if a couple does not become pregnant after more than 24 months despite regular, unprotected sexual intercourse, contrary to their explicit will. (see also infertility )

The way out of adopting a child is de facto blocked in many cases, as many couples do not meet the requirements for adoption and the demand for adopted children in Germany and other industrialized countries is greater than the supply.

3% of all newborns in Germany in 2003 were conceived by means of in vitro fertilization. In the course of the Statutory Health Insurance Modernization Act , the assumption of costs for artificial insemination was greatly reduced. Since then, at least 15,000 fewer children have been born each year. In 2011, Federal Family Minister Schröder started a discussion about it (“I find it unbearable when wishes for children fail because of money”) and thought about how the outdated German adoption law could be simplified.

Prejudices against childless people

Often the fact that someone is middle-aged or older has no children is seen as an expression of "child hostility". Apart from the fact that unintentionally childless or “ orphaned parents ” are wronged, childlessness does not automatically mean “distance to children” even for fertile people. In her essay The Childless and Demographic Peace , Judith Klein writes: “In European literature there is a long tradition of recognizing the contribution of the childless to the emotional development as well as to the care, comfort and upbringing of children - a tradition that is becoming more and more popular Oblivion. In the 16th century, Michel de Montaigne made no distinction between the (biological) father's affection for his child and the - always possible - affection of another person for that same child. "

Trivia

The word childless was one of the words of the week in July 2004 - triggered by the tax reforms in Germany and Austria as well as the discussion about family and pension policy .

See also

- adoption

- Age pyramid

- Antinatalism

- Demographics

- Mackenroth thesis

- care insurance

- Pill break

- Population development

- Population decline

literature

- Christine Carl: Life without children. When women don't want to be mothers. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2002, ISBN 3-499-61384-0

- Jutta Fiegl: Desire for children, the mysterious interplay between body and soul. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-530-40161-7

- Susanne Gaschke : The emancipation trap - successful, lonely, childless. C. Bertelsmann 2005, ISBN 3-570-00821-5 Review

- Sebastian Schnettler: Growing old without children. The social support relationships of childless people and parents in Germany. VDM, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 3-8364-6806-9

Web links

- Social science data on research into childlessness and the number of children (PDF) Federal Institute for Population Research (BiB), 2015

- Wanted or unwanted? The state of research on childlessness (PDF) Federal Institute for Population Research (BiB), 2015

- Why do some men become fathers and others not? University of Basel, 2010

- Statistics on births, including data on childlessness . Federal Statistical Office (Destatis)

- Desires for children in Germany - consequences for a sustainable family policy. (PDF; 282 kB) Bosch Foundation, 2006

Individual evidence

- ↑ Federal Ministry for Family, Seniors, Women and Youth: Childless women and men. Berlin 2014, p. 23 (PDF; 7.1 MB; 190 pages), accessed on March 4, 2019.

- ↑ statista.de: Fertility rate in Austria from 2007 to 2017 (children born per woman) , accessed on March 4, 2019.

- ↑ statista.de: Total fertility rate in Switzerland from 2007 to 2017 (children born per woman) , accessed on March 4, 2019.

- ↑ statista.de: Total fertility rate *: Development of the fertility rate in Germany from 1990 to 2017 , accessed on March 4, 2019.

- ↑ destatis.de: Final childless rate by year , accessed on March 4, 2019.

- ^ Walter Bien, Hiltrud Bayer, Renate Bauereiß, Clemens Dannenbeck: The social situation of childless people . In: Walter Bien (Ed.): Family on the threshold of the new millennium. Change and development of familial ways of life. DJI Familiensurvey Vol. 6, Leske and Budrich, Opladen 1996, ISBN 3-8100-1713-2 , pp. 97-104.

- ↑ Rosemarie Nave-Herz: Childless marriages. An empirical study of the life situations of childless married couples and the reasons for their childlessness. Juventa, Weinheim / Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7799-0688-0

- ↑ Klaus A. Schneewind: Conscious childlessness: Subjective Justification factors in young married couples. In: Bernhard Nauck, Corinna Onnen-Isemann (ed.): Family in the focus of science and research. Luchterhand, Neuwied u. a. 1995, ISBN 3-472-02153-5 .

- ↑ Christine Carl: Life without children. When women don't want to be mothers . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2002, ISBN 3-499-61384-0

- ↑ Three groups of intentionally childless people. Single-Generation.de

- ↑ Christian Schmitt, Ulrike Winkelmann: Who Remains Childless? Socio-structural data on childlessness of women and men. (PDF; 290 kB) German Institute for Economic Research e. V., 2005.

- ↑ Unwanted childlessness . Federal Ministry for Family, Seniors, Women and Youth, Paderborn 2015, p. 23.

- ↑ Dirk Konietzka · Michaela Kreyenfeld (ed.) - A life without children - Childlessness in Germany - Publishing house for social sciences - GWV Fachverlage GmbH, Wiesbaden 2007 - ISBN 978-3-531-14933-2

- ↑ 1970 census, only German women, only children born in wedlock, reproduced from Kreyenfeld, page 27, table 5

- ↑ Dorbritz, Jürgen; Schwarz, Karl 1996: Childlessness in Germany - a mass phenomenon? Analysis of manifestations and causes. In: Journal for Population Science 21.3: 231-261

- ↑ SOEP 2005, For cohorts 1900-39 based on sub-samples A and B of the SOEP with weighting factor bphrf. For cohorts 1940-59 women of sub-samples A, B, DF who lived in the western federal states in 2005 with weighting factor vphrf. reproduced from Kreyenfeld on page 28, table 6

- ↑ General population survey of the social sciences (ALLBUS) 2000, 2002, 2004, pooled data, women over 40, West Germany, stepchildren and adopted children are not taken into account, reproduced from Kreyenfeld, page 28, table 6

- ↑ DJI Family Survey 2000, panel population excluded, weighting factor hr_hs, reproduced from Kreyenfeld, page 28, table 6

- ↑ Fertility and Family Survey 1992, German women who were 38-39 years old in 1992, reproduced from Kreyenfeld, page 28, table 6

-

↑ Microcensus, childless women aged 38-39, West Germany, microcensus 1973-1991: The calculations refer to people in private households at the family's main residence. The number of children was generated from the sum of the children in the family.

Microcensus 1996-2004: The calculations refer to persons in private households at the main place of residence of the cohabiting community. The number of children was calculated as the sum of the children in the community. - ↑ Microcensus, childless women aged 38-39, East Germany

- ↑ Microcensus 2008, Germany, all children born

- ↑ a b Institute for Economic Research e. V .: Beate Grundig: Childless women vs. Women without children: The problem of measuring childlessness in Germany. In: ifo Dresden reports. 5/2006 (PDF 91 kB).

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office: How do children live in Germany? Accompanying material for the press conference on August 3, 2011 in Berlin ( memento of November 6, 2011 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Nicole Auferkorthe Michaelis, Sigrid Metz-Gockel, Jutta Wergen, Annette Klein: Young Parenthood and science careers. (PDF; 350 kB) Zeit Online , p. 1, University of Dortmund - University Didactic Center; Retrieved March 11, 2008.

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office Germany: New data on childlessness and births. Press release No. 470 from December 9, 2008.

- ^ Die Welt : Study: More and more German women remain childless. July 29, 2009.

- ↑ Own calculations by the Federal Institute for Population Research based on the 2012 microcensus ( PDF; 391 kB ( Memento from November 25, 2015 in the Internet Archive ), p. 12).

- ↑ a b Björn Schwentker : End of Discrimination? Zeit Online , July 6, 2007.

- ^ Judgment ( Memento of May 8, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) of the Lower Saxony Finance Court of August 19, 2003, Az. 13 K 323/02 (DOC; 38 kB).

- ^ Agricultural social insurance Baden-Württemberg: higher contributions to long-term care insurance for childless people. 2004.

- ↑ Hans-Werner Sinn : Pension amount according to the number of children. The constitutional court ruling on long-term care insurance must be taken into account in relation to retirement benefits. World on Sunday , April 8, 2001.

- ↑ Less pension for childless? The evaluation of child-rearing for the statutory pension is controversial. FAZ , September 11, 2003.

- ↑ 50 euros less for parents. CSU: Childless people should pay more for their pension. Wirtschaftswoche , March 8, 2004.

- ↑ Perspective Germany survey: Better care - more children . ( Memento of October 24, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 110 kB) Perspektive-Deutschland.de

- ↑ Charlotte Höhn, Andreas Ette, Kerstin Ruckdeschel: Desires for children in Germany - consequences for a sustainable family policy. Robert Bosch Foundation, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-922934-99-8 , p. 16.

- ↑ Anja Langness, Ingo Leven, Klaus Hurrelmann: Young people's worlds: family, school, leisure . In: Klaus Hurrelmann, Mathias Albert: 15th Shell Youth Study - Youth 2006. ISBN 978-3-596-17213-9 , p. 54.

- ^ Stefan Dietrich: Sham fatherhood. Deaf legislators. FAZ , July 29, 2006.

- ↑ Draft law to supplement the right to challenge paternity. (PDF; 350 kB) German Bundestag, printed matter 16/3291.

- ↑ No money and no career - why Germans don't have children . ( Memento from May 3, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Foundation for Future Issues - an initiative by British American Tobacco, Research News, 248, 34th year, August 1, 2013.

- ↑ Children = no money, no freedom, no career? Why the Germans don't have children . ( Memento from October 26, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Foundation for Future Issues - an initiative by British American Tobacco, Research News, 270, 37th year, October 12, 2016.

- ↑ Involuntarily without children . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , June 27, 2007.

- ^ A b Phillip Longman: The Empty Cradle: How Falling Birthrates Threaten World Prosperity And What To Do About It. Basic Books, New York 2004, ISBN 0-465-05050-6 .

- ↑ Lars Gaede: Lonely together: fish meets bike. Spiegel Online The secret of the middle - how Germans live, how they love what they think . In: Der Spiegel . No. 17 , 2008, p. 85 ( online ).

- ↑ The secret of the middle - how Germans live, how they love what they think . In: Der Spiegel . No. 17 , 2008, p. 75 ( online ).

- ^ Meike Dinklage: procreation strike. ( Memento from August 1, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) single-generation.de, March 14, 2005.

- ↑ Manfred Spieker: More children or more employees? Federal Agency for Civic Education

- ^ Institute for Demoskopie Allensbach : Influential factors on the birth rate. Results of a representative survey of the 18 to 44 year old population. ( Memento of November 28, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 370 kB) p. 9

- ^ Postadolescence . ( Memento of April 13, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Schader Foundation .

- ^ Federal Ministry for Family, Seniors, Women and Youth: Hans Bertram, Wiebke Rösler, Nancy Ehlert: Sustainable Family Policy. Securing the future through a triad of time policy, financial transfer policy and infrastructure policy. Section II. ( Childlessness and devotion to work ) (PDF 690 kB).

- ^ Federal Ministry for Family, Seniors, Women and Youth: Monitor Family Demography. Issue No. 1 - Germany: Childless despite the desire to have children. (PDF; 1.5 MB) 2005.

- ↑ Kurt Biedenkopf et al .: Strong family. Report of the Commission “Family and Demographic Change”. (PDF; 1.5 MB) Robert Bosch Stiftung, 2005, archived from the original on October 22, 2007 ; Retrieved June 13, 2008 ( ISBN 3-922934-96-X ). , P.56.

- ↑ Brochure “Births in Germany”. Federal Statistical Office, 2012 edition, p. 37.

- ↑ Jan M. Hoem, Gerda Neyer, Gunnar Andersson: Childlessness and educational attainment among Swedish women born in 1955-59. (PDF; 620 kB) In: MPIDR Working Paper WP 2005-014. June 13, 2005, accessed June 13, 2008 . P. 16 (PDF)

- ↑ Charlotte Höhn, Andreas Ette, Kerstin Ruckdeschel: Desires for children in Germany - consequences for a sustainable family policy. Federal Institute for Population Research , p. 32.

- ↑ Seehofer stirs up fear of lack of food. Welt Online , April 30, 2008.

- ↑ Definition of “childlessness (unwanted)” . Federal health reporting.

- ^ Christiane Bender: Adoption in Germany . ( Memento from May 15, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Helmut Schmidt University, Hamburg 2006.

- ↑ Without children on the sidelines. - According to Minister Schröder, wishes for children should no longer fail because of money and outdated regulations. Tanja Dückers about the new mother image and unwanted childlessness . Zeit Online , June 3, 2011

- ^ Citizen knowledge Germany / Germany and the Germans / population. ( Wikibooks ) Discussion about “child hatred”.

- ↑ Judith Klein: The childless and the demographic peace. In: Frankfurter Hefte. Edition 12/2005.

- ↑ Interview with Christine Carl on the subject of life without children. When women don't want to be mothers. .