Clothing fashion at the time of the Thirty Years War

With the beginning of the 17th century there was increasing resistance to the rigid nature of Spanish fashion , although some of it continued to have an effect until around 1640. The clothing fashion at the time of the Thirty Years War was characterized by a striving for more comfort , freedom and a natural, casual elegance .

Influences

The epoch between around 1620 and 1650 is a transition period that does not show a completely uniform picture. In different countries there were clear differences, depending on whether one was even more oriented towards Spanish fashion (including religion and culture) - Spain held onto its own, very conservative and strict clothing for a long time - or the more recent influence of France followed, which later finally prevailed from around 1650.

It is sometimes said that the fashion of the period was influenced by the Netherlands or Flanders. However, this impression is mainly due to the simultaneous heyday of painting in these countries with a veritable flood of genre pictures and portraits , and is less likely to reflect the actual circumstances regarding a Dutch influence on general fashion. On the contrary, portraits by painters such as Frans Hals , Rembrandt , Verspronck and other painters show that the wealthy, Reformed citizens of the northern Netherlands tended to dress in a more ascetic-puritanical style with lots of black and less ornamentation and lace than the general early Baroque fashion trend.

Interestingly, there was a similar, albeit somewhat different, tendency towards ascetic black, unadorned collars ( golillas ) and robes in the highly Catholic south of all places, especially in Spain, which was sidelined during this time (and not just in fashion), especially in the Women's fashion, where the hoop skirt was not only retained, but even widened to enormous dimensions around 1650–1670 (see portraits by Velázquez and others).

The costume got its character partly from the Thirty Years' War , but from the 1620s onwards, international fashion was increasingly influenced by France, which was less heavily involved in the war. The most elegant and progressive clothing - what is known as the 'latest fashions' - was worn at the French court and in England (under French influence) during this period, which can be regarded as fashionable trailblazers. Engravings by Abraham Bosse and Wenzel Hollar , for example , as well as portraits of the Beaubrun brothers from the French court, and especially the portraits of Anthony van Dyck , who worked for many years at the court of Charles I of England and his French wife Henrietta Maria, bear witness to this .

In Germany from around 1630 there was a literature that resisted French fashion and everything " Wälsche ", which authors such as Grimmelshausen , Logau or Moscherosch perceived as "un-German" and stupid. Especially the "à la mode" dressed gentleman was mercilessly targeted.

There have been various attempts to curb excessive clothing luxury and the tendency towards lace and ornaments; in France itself, for example, this was attempted by an edict of 1633 (see illustration by Abraham Bosse). Apparently it was of little use.

- Reform clothing according to the edict of 1633

A nobleman changes his splendid robes for simpler ones according to the Edict of Dress of 1633 (engraving by Abraham Bosse ).

General characteristics

Compared with the previous emphasis on a tall and slender figure, the silhouette in the 1620 to 1650s was significantly more rounded and broader for both sexes. However, this impression was achieved less through stuffed and padded clothing - as in Spanish fashion - but on the one hand through high-waisted robes for both sexes (especially from around 1630), and on the other hand through wide cuts and large, expansive masses of fabric, both for pants and also for skirts; with men also through wide capes and coats.

The early baroque fashion also had a tendency towards playful, flowery, and lovable: It was (as before) characterized by a great and general preference for lace , which was worn by both sexes mainly on collars and cuffs , and by women also on bonnets , by men also on the sash or on the knees. There were also ribbons, bows and rosettes . The Spanish ruffles gradually went out of fashion and gave way to more and more flat and wide collars.

The transitions to fashion under Louis XIV are fluid, as this already knew an early phase that began around 1640. In particular, around the middle of the century, the waists gradually slide back into their normal position. Overall, the trend is now moving more in a higher, leaner direction.

Menswear

In the men the image certain now a hochtailliertes jacket with wide tails and a long skirt, about a latter in the form of equal Koller . Sometimes the doublet was provided with decorative slits on the sleeves or chest, from which the white undershirt protruded. In the 1620s, ruffs were still worn, but more and more often they were not strengthened, so they fell loosely and casually on the shoulders; in official costumes z. B. in the Netherlands the frill lasted a little longer. Otherwise, a wide lace collar has now become fashionable. T. covered the whole shoulders. This included very wide, about knee-length bloomers , which were no longer stuffed as before, but fell in loose folds around the thighs. The trousers were often tied with a bow at the knee and were initially high-waisted to match the doublet, i.e. the waist was above the stomach before it slipped back down to its natural position in the middle of the century.

The costume was completed by a supported on a wide Vandelier Degen and a large Schlapphut : a soft felt hat with a wider, front, side or rear at two locations positioned brim, the one or more ostrich feathers was decorated.

United were (necessary and in war) fashionable high, to below the knees reaching boots made of leather, which was usually kept the natural color, with teeth or on the edge of tips provided and large spores to spread, often the whole foot covering spores leathers. This clothing was worn not only by mercenaries and soldiers during the war, but also by educated men. The high boots were turned over at the cuff above or below the knee ( gauntlet boots ), or the boots were pushed down far so that the trousers could be seen, which sometimes had lace trim or were decorated with ribbons. Representations in paintings by Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck or The Night Watch by Rembrandt are well known.

In the courts or in a less warlike context, low shoes were also worn, which could be open on the side and were very often decorated with a large bow or a large rosette (engravings by Abraham Bosse , Callot , paintings by Dirck Hals, etc.) .

The gentlemen also wore lots of lace, bows and ribbons. With so-called fashion freaks , this costume could 'degenerate' - at least from the point of view of the German critics or the English puritans .

The men's hair grew longer and longer between 1620 and 1650, and it often fell to the collar. After 1630, wavy and curly hair also became fashionable. Some men even let one or two long strands grow on the back of their necks, which could also be braided into a pigtail or tied with a bow - this hairstyle was called 'Cadenettes' after Marshal Cadenet. In addition, a (sometimes slightly twisted) mustache and a short goatee.

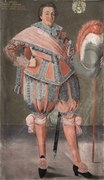

- Men's fashion 1620-1650

Anthony van Dyck : Thomas Howard, Second Earl of Arundel , 1620-21

Frans Hals : The Laughing Cavalier , 1624

Peter Paul Rubens : Albert and Nicolaas Rubens (sons of the painter), approx. 1626–1627

Jakob Elbfas: Gustav II Adolf of Sweden , ca.1630

Frans Hals : Willem Heythuijsen , 1634

Abraham Wuchters : Christian IV of Denmark , 1638

Frans Hals: Adriaen van Ostade , approx. 1645–1648

Womenswear

Similarly, the costume of women changed. The Spanish hoop skirt ( vertugade ) disappeared and the skirt now fell in soft folds. Fullness was achieved with the help of numerous petticoats of various colors or patterns that were often shown to be visible under the upper skirt. Later the upper skirt was sometimes open from top to bottom, so that another skirt peeked out from underneath.

The women's camisole was initially similar to Spanish fashion, but became shorter and shorter from around the end of the 1620s, and was then high-waisted from around 1630 to around 1650. The sleeves were fluffy, at first they were probably also padded, but they too were gradually shortened and widened. In addition, wide lace cuffs that were initially strengthened and later softened and slowly transformed into the high baroque shape.

The ruff was still very common in the 1620s and lasted a little longer in women's fashion, especially in the Netherlands (partly until the 1640s). Now, however, you wore necklines that got bigger and bigger and were mostly framed by a wide lace collar, which could partly cover the cleavage . Large stand-up collars ( medici collars ) were also worn on festive robes until the beginning of the 1630s. Later the shoulders were also bared and the collars became smaller and softer.

In the beginning, the women tucked their hair back relatively easily, but the hairstyles also tended to tend towards width, which was achieved by simply leaving the hair open at the temples and wearing it in bulk. At the end of the 1620s, it was even shortened over the ears, later waved or curled, the sidelocks became gradually longer and finally fell down to the shoulders from around the end of the 1630s - the trend in fashion went more and more towards curls.

Women could also wear a feather-adorned felt hat with a folded brim, as well as fans and masks against sun, wind and weather. On a ribbon around the waist you could carry fans, watches and even a hand mirror. The most popular jewelry for women was pearls .

Fashion 1620–1650: women

- Women's fashion 1620-1650

Philippe de Champaigne : The Artist's Wife, Charlotte Duchesne , approx. 1630–1635

Frans Hals: Portrait of a Woman (Aeltje Dircksdr. Pater?) , 1638. The millstone frill is valued in Holland for a long time.

Charles and Henri Beaubrun : Françoise Marguerite du Plessis Chivré (1608-1689), niece of Richelieu , wife of Antoine III. de Gramont , with her son Antoine-Charles IV. (1641–1720) , ca.1645

Frans Hals : Smiling Woman with a Fan , 1648–1650

Lorenzo Lippi : Maria Leopoldine (1632-1649), 2nd wife of Ferdinand III. , 1649

Hendrik Münnichhoven : Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie with Maria Eufrosyne von Pfalz-Zweibrücken , 1653

Original robes around 1620–1640

Gala robe of Gustav II Adolf of Sweden (collars, cuffs and ribbons or bows are missing), behind it a pompous saddlecloth ( Livrustkammaren , Sweden)

See also

- Louis-Treize (architecture, fine arts, interior decoration from the same era)

- Spanish fashion

- Clothing fashion at the time of Louis XIV.

- Rococo clothing fashion

literature

- Bert Bilzer: Masters paint fashion . Georg Westermann Verlag, Braunschweig 1961, p. 39.

- Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977.

- Erika Thiel: History of the costume , 8th edition. Henschel-Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-89487-260-8 , p. 209.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 177.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion ... , ..., Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 : p. 178.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion ... , ..., Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 : p. 178.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion ... , ..., Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 : p. 177.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion ... , ..., Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 : p. 177.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion ... , ..., Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 : p. 179, p. 184–185.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion ... , ..., Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 : p. 177 and 324.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion ... , ..., Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 : p. 177.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion ... , ..., Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 : p. 177.