Clothing fashion at the time of Louis XIV.

During the time of Louis XIV (1638–1715), after the Thirty Years' War , France gained dominance in Europe from around 1660. It became a model in all possible fields, in science, architecture, horticulture, interior design. For centuries, French became the language of the cultured, educated classes and the aristocracy. The court in Versailles set the tone for almost all countries in terms of customs and fashion .

In terms of clothing and hairstyles, France had already developed its own style in the decades before, during the 30 Years' War, and had already exerted a certain influence. But this supremacy was consciously and purposefully promoted by Louis XIV, not least out of mercantile interests. For example, the production of silk was stimulated - the city of Lyon became a famous center for centuries - as well as the production of lace, in which Venice had specialized up until then .

In addition, journals were printed in which one could see images of the latest fashions from Versailles - such as B. the Recueil des modes de la cour de France - and one already knew fashion dolls that served as illustrative material and were regularly sent to European courts and European capitals dressed after the 'latest craze'.

Since Louis XIV came to the throne at the age of five and it was a fairly long reign, the fashion between around 1650 and 1715 did not remain completely uniform, but changing fashions for both sexes can be determined. The epoch can be roughly divided into an early phase up to around 1670, a transition period from around 1670 to 1680, and a late phase from around 1680 or 1685 to 1715.

Menswear

Until about 1670

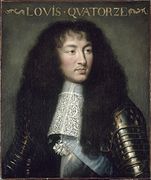

From the perspective of the 19th to the 21st century and also in comparison with previous epochs, men's fashion of this era is considered to be relatively feminine. The king himself was the number one fashion icon in every respect .

In the youth of the Sun King between around 1650 and 1670, the men wore strikingly brightly colored, playful, bird of paradise-like clothing: the trousers took the form of very wide, knee-length skirt trousers , the so-called Rhingrave or Rheingrafen trousers , which were carried around the knees and around the waist enormous amounts of colored ribbons and bows made of velvet or silk , called petite oye ( goslings ). On the body a very short open doublet - almost in the manner of a bolero - from which the puffy undershirt protruded both on the sleeves and in the front, which was richly decorated with trickling tips on the cuffs and collar . Ribbons and bows on the neck, shoulders and sleeves. Over it either a wide cloak or a wide knee-length coat, and on the long curly hair a feather-trimmed hat.

The lower legs were dressed in silk stockings, plus shoes with (for men's fashion) relatively high heels, which were usually red for the king and courtiers, and were often decorated with a bow. Many gentlemen used a walking stick as a fashion style, which was also helpful because of the high heels. When riding or in war, the gentlemen still wore boots, but the brims were not as wide as in the Thirty Years' War.

- Men's fashion: approx. 1650-1670

Caspar Netscher : A man in Rheingrafenmode , 1659

Jan Mytens : Jean-Jacques de Geer , (1632–1696), around 1660

Jacob Huysmans : Sir John Chichley (approx. 1640–1691), approx. 1664

Sebastiano Bombelli : Maximilian Philipp Hieronymus von Bayern-Leuchtenberg , 1666

Gerard ter Borch the Elder J .: Memorial portrait to Moses ter Borch , 1667–1669

Karel Škréta : Ignác Jetřich Vitanovský from Vlčkovice , 1669

Gerard ter Borch : Gerbrand Pancras (formerly known as: Hendrick Casimir II, Prince of Nassau-Dietz ), ca.1670

Peter Lely : Charles II (1630–1685) , ca 1665–1670

Caspar Netscher : Christiaan Huygens , 1671

After 1670 to 1715

From around 1670, the forms of men's fashion became simpler, but more dignified and solemn. The knee-length coat narrowed and one (s) now wore a knee-length, tight-fitting, usually collarless skirt called Justaucorps ('right on the body') with wide cuffs, from which the lace cuffs still fell over the hand, and with padded side pockets; underneath a long waistcoat, the gilet , and a pair of pants called culottes that reached down to the knees, but of which only the bottom edge was visible. At first the trousers were a bit fluffy (like the Rheingrafen trousers), but then became tighter. Around the neck, or under the chin, the white jabot , a tied scarf with lace trim; the jabot was sometimes accompanied by a large colored bow. This men's suit remained modern with a few changes until the French Revolution . It was completed with gloves, a sash and a sword hanger.

In winter they wore about it as a cape-like coat over his shoulders and a very wide long tunic Coats with wide sleeves, which apparently originally came from Germany, as it it à la Brandebourg called (see below image from the " Recueil des modes ... ").

Popular fabrics for court clothing were velvet and silk . The Justeau Corps was also trimmed with braids or braids. Gold and silver embroidery on skirts and vests was generally forbidden according to a royal decree of 1664, only the king himself and a few people he chose were allowed to enjoy such a luxury. For this purpose, he issued an official permit for gold and silver embroidery, which was known as juste-au-corps à brevet , and which was originally only granted to about a dozen, later 40 people. From 1677, fine woolen cloth was also used, which was woven in France itself, in competition with England.

Rich people like Louis XIV and his brother Philippe d'Orléans were able to wear their garments on special occasions, such as B. Receptions of ambassadors from foreign countries, adorn with a whole parure of diamonds or other precious stones; Such a gemstone set for the gentleman consisted of jewel buttons , eyelets and skirt fasteners. Also Degengehänge , religious , knee ligaments or shoe buckles could be decorated with diamonds. There were also cheaper imitations for the less well-off gentlemen.

- Men's fashion from: Recueil des modes de la cour de France , 1675-1688

Winter jacket à la Brandebourg , Nicolas Bonnart (1637-1717), ca.1675-1686

- Men's fashion: approx. 1670-1715

René-Antoine Houasse : Louis XIV on horseback, approx. 1670–1674

Claude Lefèbvre : Louis II. De Bourbon, prince de Condé with his son , approx. 1675. The great Condé was one of the elect who was allowed to wear gold embroidery.

Pierre Mignard : Louis François Marie Le Tellier , Marquis de Barbezieux (son of Louvois), ca.1690

Godfrey Kneller : Kingston, Burlington and Berkeley (Evelyn Pierrepont, 1st Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull (around 1655-1726); Charles Boyle, 2nd Earl of Burlington (1660-1704); John Berkeley, 3rd Baron Berkeley of Stratton (1663–1697)), ca.1690–1697

Hyacinthe Rigaud : René de Froulay de Tessé (1648-1725), maréchal de Tessé , 1700. Justaucorps made of exquisitely shimmering salmon-red velvet with golden braids and braids .

Hyacinthe Rigaud : Louis de Bourbon, duc de Bourgogne (1682–1712), 1704. The Dauphin is depicted here as a hero in armor - not a rare sight given the all-too-frequent wars.

Godfrey Kneller : Admiral Edward Russell, 1st Earl of Orford (1652–1727) , around 1710. A velvet Justau corps is also worn in England.

Nicolas de Largillière : Victor Marie d'Estrées, Duc d'Estrées , 1710

Men's hairstyle and allonge wig

As early as around 1620 men began to wear their hair longer and longer, initially shoulder length, but in the youth of Louis XIV. From around 1650 a long curly 'lion's mane' became fashionable, which was not given to every man - especially not permanently and as it progressed Age. As early as around 1633, wigs gradually began to appear for fashion-conscious men, and in 1656 the 18-year-old king, who at that time still had his own magnificent long and dark hair, allowed 48 wig makers in Paris. This is how the allonge wig developed , which Ludwig himself only wore from 1672. Young men continued to sport their own hair until at least the 1680s, but the hairstyle became more and more elaborate and pompous and the curls of the allonge wig reached truly splendid dimensions between around 1680 and 1715. From around 1690 it was also increasingly powdered, so that from around 1700 only white powdered curls could be seen - however, until the end, Louis XIV wore his own natural color, i.e. dark hair.

Because of the high and elaborate powdered allong wigs, hats became obsolete, especially after 1680, and therefore became increasingly flat; you almost only carried them under your arm, and in this case too it was strictly regulated by etiquette who was allowed to wear hats in the presence of the king.

Initially, until the 1670s, people still wore a small mustache with their long hair; from around 1680, a clean-shaven face was modern.

- Men's hairstyles approx. 1650-1715: Real hair and allonge wigs

Charles Lebrun (?): Louis XIV , ca.1662

Peter Lely : James II. Stuart (1633-1701), ca. 1660-1665

Gerard ter Borch : Self-Portrait (Detail), 1666–1670

Jacob Ferdinand Voet (1639–1689): Augusto Chigi, son of Agostino Chigi and Maria Virginia Borghese , around 1660–1670

Jacob Ferdinand Voet : Jean de Souhigaray , around 1660–1670

Jacob Ferdinand Voet (1639–1689): Philippe, Duc de Vendôme (1655-1727), Grand Prior of the Knights of Malta in France , approx. 1675–1685

Paul Mignard (?): Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632–1687), around 1680

Nicolas de Largillière : The painter Adam Frans van der Meulen (or Pierre van Schuppen?), 1680

Nicolas de Largillière : Portrait of a gentleman in a red robe , around or after 1700. Lush, powdered curls.

Nicolas de Largillière : Portrait of a gentleman , around or after 1700. Powdered blonde wig.

Nicolas de Largillière : Anton Ulrich von Braunschweig , before 1704 (?). Even German princes are in no way inferior!

Godfrey Kneller : Self-portrait with a wig , around 1700. In England, a smaller, somewhat angular wig appears, with shorter hair, especially on the sides.

Godfrey Kneller : Charles Lennox, 1st Duke of Richmond and Lennox , around 1703-1710

Godfrey Kneller : Francis Godolphin, 2nd Earl of Godolphin , 1710-1712

Nicolas de Largillière : Jehan-Baptiste Roze Moussard . Huge powdered golden blonde allonge wig.

Womenswear

1650 to about 1670

In contrast to the earlier Spanish fashion , which in Spain itself was still worn in a modified form until at least the 1660s, the French women's fashion of the baroque period emphasized feminine forms. From 1650 to around 1670, women wore a laced bodice (a kind of corset ) that tapered to the front and lifted the bust. The front of the bodice was often decorated, e.g. B. with borders or embroidery. At first the waist was not very emphasized, but from 1660 it was gradually tied tighter and tighter. In addition, a large oval cleavage that showed the shoulders and half of the breasts and was edged with either lace, muslin or transparent gauze fabrics, which were sometimes painted with floral motifs. The sleeves of the dress were still quite wide in this early period, they only reached to the elbows, underneath, as a counterpart to men's fashion, the puffy sleeves of the undershirt with flounces and lace cuffs could be seen. Bows and ribbons on the bodice and sleeves.

The skirt of the dress fell freely and in puffy folds, sometimes there was a small train. The upper garment ( jupe de dessus - 'overskirt') was also called manteau . This was sometimes open at the front and showed a different skirt, often in a different color, fabric or pattern. Between 1650 and 1670, light colors were modern in women's fashion, and a white silk dress was classically current.

- Women's fashion approx. 1650-1680

Pierre Mignard: Madame de la Sablière , ca.1660-1670. A light blue silk dress that is decorated with the finest embroidery on the front of the bodice and skirt and on the hem. The lady-in-waiting lifts the upper skirt a little to reveal the petticoat made of silver-white moiré - the so-called Friponne (" mischievous ").

Charles Beaubrun: Françoise Madeleine d'Orléans, Duchess of Savoy , ca.1655-1660. A very splendid robe: under a dark green silk manteau with white lapels, a skirt made of pearly, shimmering pink-patterned satin with gold embroidery. Pearls everywhere : on the neck, ears, in the hair, on the bodice and on the neckline.

Pierre Mignard : Henriette d'Angleterre , duchesse d'Orléans , called "Madame", approx. 1661-1665. As a member of the royal family, the sister-in-law of the Sun King is allowed to wear golden lilies on a blue background, plus large diamond parures.

Jan Mytens : Henriette d'Angleterre , around 1665. A simple red silk dress in English style.

Caspar Netscher : Lady Philippina Staunton , 1668

Jacob Ferdinand Voet : Princess Teresa Pamphilj Cybo (1654-1704), ca.1670-1674. A manteau made of sky-blue, gold-striped silk draped slightly back on the sides over a red skirt with splendid gold and silver embroidery. Decor of red ribbons and exquisite lace.

François de Troy (?): Liselotte von der Pfalz with a Moor , ca.1680

Benjamin von Block : Archduchess Maria Antonia (1669-1692), 1684. People are a bit old-fashioned at the Viennese court.

After 1670 to 1715

Between 1670 and 1680 women's fashion also changed, parallel to the men's. The silhouette became narrower and taller after 1680. People began to drape the open front manteau and tie it up with ribbons, agraffes or rosettes until, in the 1680s, it assumed the ruffled and draped shape of a cul de paris that could end in a train . The permitted length of such a train was precisely regulated: for duchesses who belonged to the highest nobility, B. be three cubits long - the lower the rank, the shorter the train. Towards the end of the 17th century, small linen cushions (criades) were worn under the manteau in order to give it a more curved and puffy shape. The lower skirt visible at the front was sometimes decorated with fringes , ruffles or flounces .

At home or in a less formal setting, people took off their heavy and solemn manteau and wore a more comfortable house robe , a déshabillé .

The necklines also changed over time and became a little smaller from 1680, the shoulders were now often covered, and depending on the fashion, the necklines were more elongated or V-shaped. In winter and summer, you covered your bare forearms outdoors with long gloves, and in winter you had to wear a muff . As a covering for the cutout, the palatine came into fashion from around 1676 through Liselotte von der Pfalz .

The fabrics that were particularly popular were silk, atlas and velvet, which could be splendidly embroidered with gold on particularly festive occasions such as ambassador receptions; gold and silver brocade were also used, especially for the manteau, if one could afford it. The ladies' shoes had high, rather sloping heels; they were mostly matched to the dress and could also be embroidered or garnished with silk ribbons and bows.

An absolute must was a white complexion (like centuries before and after), which you protected outdoors with a mask and in summer with parasols and embellished with white make-up and blush - but make-up seems to be compared to the customs of the 18th century . Century, at the time of the Rococo , still kept within limits. In fashion journals or copperplate engravings from life in Versailles or the royal family, women were already wearing the first mouches (cosmetic plasters) on their faces towards the end of the 17th century , but this did not occur until the Rococo in contemporary portrait art.

One of the essential accessories was a fan , and maybe even a walking stick for a walk. As before, pearls were particularly popular as jewelry, not only worn as chains or earrings , but also on dresses or in hair. Diamonds were also popular with women, and of course only the richest people could afford them.

- Women's fashion from: Recueil des modes de la cour de France , 1683-1687

Winter garment with a fur-trimmed skirt and a muff (Jean Dieu de Saint-Jean, Jean Berain , 1683)

- Women's fashion approx. 1680-1700

Nicolas de Largillière (?): Liselotte von der Pfalz , approx. 1685-1690 (?)

François de Troy : Marie Anne de Bourbon (1666-1739) , ca.1690

Madame de Montespan , fashion copper, about 1685-1691

Godfrey Kneller : Mary II of England , 1690 (diamond parure!)

Pierre Gobert : Louise Francoise de Bourbon (?; 1673-1743) , approx. 1690. Exotic carnival costume for a masked ball.

Simon Dequoy: Anne de Souvre (1646-1715), 1695. Dark blue silk robe with gold braid and hochgerafftem Manteau, to white gloves and a spitzengarnierte Fontange .

François de Troy : Marie Adélaïde de Savoye (1685-1712), 1697 (dated)

Nicolas de Largillière : Catherine Coustard with her son Léonor , ca.1700

- Women's fashion approx. 1700-1715

Pierre Gobert : Françoise Marie de Bourbon (1677-1749), Duchesse de Chartres , early 18th century

Hyacinthe Rigaud : Marie Anne de Bourbon, princesse de Conti (1666-1739) , ca.1706 (?)

Hyacinthe Rigaud : Liselotte von der Pfalz , Duchess of Orléans , 1713

Nicolas de Largillière : Madame Titon de Cogny, ca.1713-1715

Women's hairstyles

Already from around 1640 to around 1670 people wore a hairstyle " á la Sévigné " - which was probably only later named after the famous letter writer, the Marquise de Sévigné . The hair was pinned up in a bun at the back, completely flat on the head, but on the sides the hair was left loose and curled over the ears and down onto the shoulders; Depending on the fashion, there were a few little curls over the forehead. The exact shape of the side curls changed somewhat, and in the 1660s they were styled higher and fluffier over the ear, in a kind of tuff from which a long curl of corkscrews sometimes fell down on both shoulders.

At the beginning of the 1670s, a hairstyle consisting entirely of small curls developed from this called " Hurluberlu " or " Hurlupée " ("cabbage hairstyle "), which the aforementioned Madame de Sévigné described in a letter as "simply ridiculous": "The king and all sensible ladies almost died of laughter ". However, the Hurluberlu hairstyle prevailed for the next decade until around 1680 and was also worn by the marquise.

- Louis XIV fashion: women's hairstyles ca.1650-1680

Charles Beaubrun : Marie d'Orléans, Mademoiselle de Longueville as a young girl , ca.1640

Charles Beaubrun (workshop): Françoise de Rochechouart , later Madame de Montespan , before or around 1660

Peter Lely : Henriette, Duchesse d'Orléans , 1662

Anonymous: Françoise-Athénaïs de Rochechouart, Madame de Montespan (detail), approx. 1663-1667

Peter Lely : Catherine of Braganza , Queen of England , 1665

Peter Lely : Lady Frances Savile, later Lady Brudenell , ca.1668 (?)

Jacob Ferdinand Voet (1639-1689): Maria Ortensia Biscia del Drago , approx. 1668-1673

Anonymous: Liselotte von der Pfalz , approx. 1671. This is a Hurluberlu (cabbage hairstyle ).

Caspar Netscher : Suzanna Doublet-Huygens (1637-1725), around the beginning of the 1670s ( Hurluberlu !)

Jacob Ferdinand Voet (1639-1689): Ortensia Mancini , duchesse de Mazarin , 1671

Jacob Ferdinand Voet (1639-1689): Maria Mancini , approx. 1673-1678

Caspar Netscher : Cecilia de jonge van Ellemeet , 1679. A very simple hairstyle with hair pulled back loosely.

After 1680, the hairstyle, held in place by ribbons, tended more and more upwards and became the solemn female counterpart to the men's high allonge wig. The invention of the Fontange - a high and complicated hairstyle with a starched and pleated bonnet and ribbons - was attributed to the Duchess of Fontanges , a mistress of Louis XIV. It lasted until the beginning of the 18th century.

Women too began to powder their hair towards the end of the 17th century, and the hairstyles became so high and complicated that Liselotte von der Pfalz said: "... I can't get used to this masquerade at all, but every day you sit higher on". In England the sedan chairs had to be raised so that the ladies could sit in them.

Around 1700 the hairstyles - allegedly due to the influence of a lady sandwich - were again lower and a bit simpler, ribbons were no longer used, but the hair was still coiffed up and the forehead was framed by curls ( cruches ) on the right and left . Liselotte von der Pfalz was relieved: "The new fashion looks pretty nice to me, because I couldn't stand the hideously high coiffure". From 1710 at the latest, this hairstyle was almost exclusively powdered white and lasted well into the 1720s.

- Louis XIV fashion: women's hairstyles, circa 1680-1715

François de Troy : Louise Françoise de Bourbon , mademoiselle de Nantes , approx. 1688-1693

Pierre Mignard (?): Marie de Lorraine-Armagnac, Princesse de Monaco , called Madame de Valentinois, ca.1690

Pierre Gobert (?): Françoise Marie de Bourbon (?), Ca.1690

François de Troy : Teresa Kunegunda Sobieska , ca 1694-1695

Nicolas de Largillière : Anne Geneviève de Lévis, princesse de Soubise , daughter of Madame de Ventadour, 1695

Hyacinthe Rigaud : Comtesse de Lignières , 1696

François de Troy : Françoise Marie de Bourbon (?), Around 1700

Nicolas de Largillière : Young girl , around 1700

Nicolas de Largillière : Jeanne Gagne de Perrigny, beginning of the 18th century

Nicolas de Largillière : Portrait of a Young Lady (Duchesse de Beaufort?), 1714

Nicolas de Largillière : Marie Elisabeth Desirée de Chantemerle , 1715

Others

Children's fashion

Small children up to the age of 6 or 7 were all dressed in the same way in this era (and even before), so there was little or no distinction between boys and girls at an early age. All children wore long 'dresses', often with aprons, to protect them from dirt. However, differences could gradually arise anyway, e.g. B. in the hairstyle, which was different for little girls than for boys, even if long hair was fashionable in both sexes. Also on accessories you could tell the sex in circumstances such. B. it could be especially with noble children that a little boy was already walking around with a (toy -?) Sword.

From around the age of 6, boys were dressed in trousers. From then on there was no longer any independent children's fashion, children were dressed like adults. For girls, this also meant that they were pressed into their own lace-up bodice ( corset ) from an early age , and the sons of the Sun King wore uniforms or even breastplates when they were well under 18 when they had to get involved in the war.

- Children's clothing in the time of Louis XIV.

Charles Beaubrun: Louis XIV (1638-1715) and his two years younger brother Philippe (1640-1701) as small children , ca.1641-1643.

Charles and Henri Beaubrun (attributed): Ludwig XIV. And his brother Philippe , approx. 1644. Here the little king is already wearing the male clothes of an adult, his brother is still in a toddler's robe.

Diego Velázquez : Prince Felipe Prospero (1657-1661), 1659. A little prince also wears a dress at the Spanish court.

Jean Nocret : Marie Thérèse de Bourbon (1667-1672). The daughter of Louis XIV, who died prematurely, and his wife Marie Thérèse are sumptuously dressed up and have a fashionable hairstyle with side curls.

Little boy in Rheingraf costume, possibly Louis, the Dauphin of France (?) (Son of Louis XIV, 1661-1711), around 1667-1670.

Sebastiano Bombelli : Max Emanuel II (1662-1726) and Maria Anna of Bavaria (1660-1690) as children , ca.1668-1669

Hyacinthe Rigaud : Louis Alexandre, Comte de Toulouse , ca 1685-1690

Antoine Pesne : Frederick the Great (1712-1786) as a three-year-old with his favorite sister Wilhelmine von Prussia (1709-1758) , 1715

Citizens and lower classes

The baroque fashion described was elaborate and costly and, just as in earlier times, primarily a fashion of the aristocracy. Large allonge wigs made from real hair were very expensive, as were the popular lace or fabrics such as velvet and silk. Apart from rich citizens, who were also oriented towards the nobility and were no longer restricted by dress codes as much as in the Middle Ages, the clothes of peasants or citizens were simpler and less colorful. Men in particular often wore black or other muted colors such as brown or gray - but brown is also said to have been Louis XIV's favorite color! Black was z. B. Typical for 'financiers', even the finance minister Colbert - who came from the middle class - was shown in pictures with a black robe.

Nevertheless, the clothes of simpler people were basically based on the current fashion silhouettes and shapes. For practical reasons, however, the skirts of ordinary women were often shorter and made of cheaper fabrics; hoods or aprons were often worn.

Overall, there were many regional differences in terms of traditional costumes .

- Simple people's clothing from: Recueil des modes de la cour de France , 1678-1693

Outside France

The French fashion ultimately prevailed throughout Europe, but there were also some characteristic peculiarities in other countries and resistance.

The most intense and longest resisted the Habsburg e Spain , where already since about 1620 or 1630 a unique fashionable development beyond the European mainstream (s) traversed. Spanish clothing was based at least until 1670 and z. Some of them still rely on the ideals of the Spanish court dress . But the stiff, high-necked shapes, the gloomy colors and the abundance of black, which had been current across Europe between 1550 and 1620, appeared hopelessly old-fashioned, joyless and dusty from 1650 at the latest against the colorful, casual and flirtatious French fashion. This impression was particularly extreme in women's fashion, where the feminine forms disappeared completely under unfavorable helmet-like hairstyles, corsets that flattened the chest, and under the Spanish hoop skirts , which had assumed absurd dimensions from around 1640 or 1650. The Spanish hoop skirts, however, were not decorated with flower garlands, ruffles or flounces, as they were later in the Rococo or in the 19th century, but appeared bulky, rigid and inelegant. Even when the hoop skirts and rigid hairstyles were later dropped and fashion became more elegant, clothing in Spain still retained numerous peculiarities around 1690 (see picture of the Spanish queen by Claudio Coello ).

In the Netherlands , wealthy people dressed similarly to those in France. A small typical peculiarity in the 1650s and 1660s were fur-trimmed jackets made of velvet or silk, which were very popular with the elegant Dutch ladies and in many pictures by painters such as Gerard Terborch , Jan Vermeer , Gabriel Metsu , Pieter de Hooch and others. a. Pop up. There were these jackets in different colors and cuts, wide or waisted, high-necked or with a neckline; the sleeves were three-quarters long and reached just below the elbows. They were particularly often worn with a silk dress.

In England , earlier than anywhere else, during the reign of Charles I (1625-1649), French trends were adopted in fashion, presumably also through the influence of Queen Henrietta Maria , an aunt of Louis XIV, of French descent.

This development was completely interrupted by the Puritan rule of Oliver Cromwell , where everything that was considered ' frivolous ' was rejected - e.g. B. large cut-outs, any ornamentation on the robe or hairstyle etc. But immediately with the accession of Charles II. In 1660 not only the manners were relaxed again, but also the French fashion returned, because the king not only had a French mother , but also lived partially in French exile, and was completely Francophile. One characteristic of English clothing, however, remained a certain simple elegance, which was even adopted in France in the late 18th century. For example, the English ladies in portraits by Peter Lely (between 1660 and 1680) or later by Godfrey Kneller wear fine, elegant silk dresses, which are much simpler than in France and elsewhere. B. have little or no embroidery, and hairstyles became very simple at least around 1700. Even men's allonge wigs took on their own, somewhat angular style in England, and were worn a little shorter even before 1700, especially on the sides (see above men's portraits by Godfrey Kneller).

In Germany many courts unconditionally adopted French fashion, especially those that were somehow related to France, such as B. Braunschweig-Lüneburg ( Liselotte von der Pfalz , the sister-in-law of the Sun King, was a niece of the Electress Sophie ) or Bavaria (the wife of the French heir to the throne Maria Anna was a Wittelsbacher ).

The Viennese imperial court found it a little more difficult - the close kinship of the Austrian and Spanish Habsburgs and their personal hostility to the Bourbons caused at least a certain delay here too. It is noticeable that the first wife of Emperor Leopold I , the former Spanish Infanta Margarita Teresa (1651-1673), was even allowed to wear Spanish fashion at the Viennese court, although this was actually a foreign body in Vienna between 1666 and 1673. That would have been unthinkable elsewhere: Her older half-sister Maria Teresa (1638–1683) was the Queen of France (!) And, of course, immediately after her marriage to Louis XIV. Six years earlier, she was dressed and haired according to local customs. By the end of the 17th century, however, Vienna was also fashionably French.

Even Russia , which until around 1700 was still completely outside of European reach and culture, was culturally and fashionably influenced by France under Peter the Great , but only towards the end of the era of Louis XIV.

Jacques Laumosnier: The Peace of the Pyrenees . At the meeting of Louis XIV (center left) with Philip IV of Spain and his daughter Maria Teresa (center right) on Pheasant Island in 1659, the stark contrast between the stiff and old-fashioned Spanish clothing (right) and the colorful, imaginative elegance of the The French (left) in their curly hair and Rheingrafen trousers with ribbons and bows and high-heeled shoes cannot be overlooked. The Infanta in the rigid and wide white hoop skirt and with a wide Spanish hairstyle was, in terms of fashion, beyond anything that was acceptable in the rest of Europe, and especially in France, at the time.

After Louis XIV.

In the time after the death of Louis XIV, a transition period began, the so-called Régence , the reign of Philippe II. D'Orléans for the still underage Louis XV. which lasted from 1715 to 1723. While court life had become very ceremonial in the last decades of the era of Louis XIV, manners were now loosening - a development that had begun among the younger people since around 1700, who no longer enjoyed themselves in Versailles, but in Paris.

All of this was also accompanied by changes in fashion. In men's fashion, it was mainly the hairstyles that changed. The huge and dramatic allonge wigs were not only powdered white, but gradually flatter and smaller. While under the Sun King on certain occasions, such as during the war, the curls of the wig were tied with a bow, this gradually became a fashion in the 1720s, especially among younger people. From about 1730 the braid was put into a hair pouch and only a few side curls remained from the side parts of the allonge wig; The hair was brushed back over the forehead in a nicely curved line. However, longer wigs were still worn for decades, but never as large as around 1680-1715.

For men, the Justaucorps with its large lapels, pockets and flaps lasted for most of the 18th century, even if there were some changes in detail depending on the fashion wave; from around 1780 the skirt tails became smaller and it developed in the direction of tails. The shoes became a little flatter and now got a buckle instead of a bow. The tight trousers were strapped under the knee over the stockings.

For women, the hoop skirt reappeared in the 1710s , which was initially not very voluminous and initially conical or bell-shaped, along with the lace-up chest . From around 1720, a robe with a horizontal neckline and so-called wadding pleats that fell elegantly down the back - the so-called Adrienne or Contouche - appeared . The hairstyles of women had already become smaller after 1700, and like the men’s wig were now mostly powdered white. They were later still lower, adorned with feathers or bows; in the back a long curl fell down on his shoulder.

Under Louis XV. Rococo fashion began around 1730 . The transitions are fluid. France was now established as the leading nation in terms of fashion and would remain so into the 20th century; Despite other international influences, Paris is still one of the world's leading fashion cities in the 21st century.

- Clothes fashion and hairstyles from 1715 to 1730

Antoine Pesne : Hereditary Prince Friedrich Ludwig von Württemberg (1698-1731) with his wife Henriette Marie von Brandenburg-Schwedt (1702-1782) , around 1716

Rosalba Carriera : Pisana Mocenigo, née Corner (or Cornaro) , ca.1715-1720 (?)

Pierre Gobert (workshop?): Françoise Marie (1677-1749) and Louise Françoise de Bourbon (1673-1743) (daughters of Madame de Montespan and Louis XIV.), Ca.1715-1720

Hyacinthe Rigaud : Lucas Schaub (1690-1758), 1721

Nicolas de Largillière: Konrad Detlef Graf von Dehn , 1724. Clothes of a stutzer : robe made of silver brocade, noble lace, made-up face, snow-white wig.

Nicolas de Largillière : Infanta Mariana Victoria of Spain (1718-1781), 1724

Nicolas de Largillière: François-Marie Arouet called Voltaire , around 1724-1725

Jean Ranc : María Ana Victoria de Borbón , 1725

Nicolas de Largillière : Sarah le Boullenger , 1725

Nicolas de Largillière : Gaspard Gédéon Pétau, Seigneur de Maulette , around 1720-1730

Nicolas de Largillière : Marguerite de Largillière , 1726

Nicolas de Largillière : André François Alloys de Theys d'Herculais (1692–1779) , 1727

Louis de Silvestre : Friedrich August of Saxony , 1727

Antoine Pesne : Reception of August the Strong in the Berlin City Palace , 1729

Rosalba Carriera : Archduchess Maria Theresa (1717-1780), 1730 (?)

Pierre Gobert : The Children of the Duke of Valentinois , ca.1730

Antoine Pesne : Princess Sophie Dorothea with Friedrich Wilhelm, Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt (1700-1771) , 1734

See also

- Louis-quatorze (style of interior decoration under Louis XIV)

- Clothing in the Middle Ages

- Renaissance and Reformation clothing fashion

- Spanish fashion

- Clothing fashion at the time of the Thirty Years War

- Rococo clothing fashion

- Revolutionary and empirical fashion

- Clothing fashion of the restoration and the Biedermeier

literature

- Bert Bilzer: Masters paint fashion. Georg Westermann Verlag, Braunschweig 1961, DNB 450468380 , p. 40.

- Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977.

- Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to the Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, pp. 189–198.

- Hélène Loetz: "Pearls and precious stones in the 17th century", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, pp. 199–204.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 189.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: pp. 189-190.

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to the Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Press C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, pp. 189–190

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Press C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, p. 191

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Press C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, p. 191

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to the Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, p. 190

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to the Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, p. 190

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to the Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, pp. 200-201

- ^ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to the Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, p. 200

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, pp. 203-204

- ^ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Press C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, pp. 190–191

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Press C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, p. 191

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Press C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, p. 191

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, p. 194

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, p. 194

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 190.

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, p. 194

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, p. 194

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, p. 194

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 450.

- ^ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to the Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, pp. 193 and 194

- ^ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to the Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Press C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, p. 198

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Press C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, pp. 199-200

- ^ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to the Fontange", in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, pp. 200-204

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 324, p. 330f (Fig. 530).

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 324, p. 330f (Fig. 530).

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", ..., Heidelberg 1996, pp. 196–197

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 323.

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", ..., Heidelberg 1996, pp. 196–197

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to Fontange", ..., Heidelberg 1996, pp. 196–197

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 342.

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to the Fontange", ..., Heidelberg 1996, p. 197

- ↑ Hélène Loetz: "The courtly fashion - From the Rhingrave to the Fontange", ..., Heidelberg 1996, p. 198

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 190.