Coleopterology

The coleopterology , the study of the beetles , is a branch of entomology . Entomology deals with insects, coleopterology with beetles as a subgroup of insects. The beetles form the order called Coleoptera within the insects. The word "coleopterology" is a combination of the Greek words for "beetle" (κολεόπτερα koleoptera) and "doctrine" (λόγος, logos , speech, sense, doctrine). A German expression is Käferkunde. Both the Greek logos and the German word -kunde include the two poles of announcing, teaching, teaching on the one hand and exploring, researching and researching on the other. Coleopterology tries to pass on the knowledge about beetles and to improve and expand it through observation and experiments.

The people who deal with coleopterology professionally or as a hobby are called coleopterologists. This is sometimes simply translated as “beetle collector”, although collecting is only part of the coleopterological work. With the coleopterologists, the transition from pure hobby to scientifically relevant work is particularly easy and is often carried out.

The tasks of coleopterology

Collecting beetles

Collecting protected beetles and collecting in nature reserves in general is prohibited. Special permits can be applied for for scientific work.

Collecting by hand includes picking up flowers or other rows of plants, picking them up from the ground, looking under stones or under loose bark, searching the ground under trees when they have been shaken, and the like. There are also devices for various other methods.

- Käschern: There are streak, water and car washers of various shapes

- Sieving: There are various special sieves that can be used to sieve out beetles from collected material.

- Tapping: One uses tapping screens or head funnels. As a temporary measure, you can also use an upside-down umbrella.

- Laying out bait cans: A can with a bait is buried up to the edge. The pheromone traps used in forestry to control bark beetle infestation are also bait boxes in a certain sense. Rare species can also be found in them.

- Creating trenches. Like the bait boxes, they are mainly used to record the ground beetle fauna.

- Soak up with a so-called Exhauster (Fig. 3)

After collecting, the beetles are cleaned and prepared according to fixed rules in order to preserve them for further investigation. To do this, the beetles must be flexible in their joints. This is the case for some time after the killing. If the beetle is already dry, it is placed in a closed container with wet absorbent paper for some time until it becomes soft again in the joints. The larger beetles are put on an insect needle by piercing it in the upper half of the right wing cover perpendicular to the body axis. Above the beetle, the needle protrudes so far that you can just grasp the needle head with two fingers. The insect needles are available in standardized sizes. The strengths 000, 00 and 0 are not used in coleopterology, most of the time they are limited to strengths 2–5, and very small needles (minutiae) and, for very large beetles, longer needles are used (Fig. 4c). The needles are supplied in different qualities in terms of head, color and finish. Sometimes, for example, a slight rusting is desirable for stable adhesion.

The smaller beetles are glued to an insect plate with water-soluble glue. Since the beetles contract due to the shrinking of the joint membranes while drying, this must be prevented by fixing the legs, feelers and possibly the buttons. In the case of smaller beetles, a superficial contact with the very thinly applied adhesive is sufficient if the limbs have first been painted with a brush. Larger beetles are inserted so deep into a dissecting block (e.g. styrofoam) that it lies on top. The limbs are then clamped in a natural position, but not too far apart, with additional needles inserted at an angle or fixed crosswise (Fig. 4a). After the beetle has dried, the needles that were used to fix it are removed. The insect plates with the small beetles are also put on an insect needle. For medium-sized beetles there is the option of needle-punching the beetle with a minutie so that it is not damaged by a needle that is too large and you don't have to glue it. The minutia is then pierced through an insect plate (Fig. 4d). To do this, the plate must be pierced with a sturdy needle and the minutie must be stuck in the hole if it is too big. The insect needles, on which the prepared beetles are directly or indirectly stuck, are now provided with labels. These are white cards about 16 millimeters long and 6 to 10 millimeters wide. The location, date and name of the collector are stated on the location slip. The scientific name of the beetle and the name of the coleopterologist who identified the beetle are noted on another piece of paper. The pieces of paper are skewered on the needle before the first letter. Other notes have very special meanings due to their color. The height of the label on the needle can be standardized by using a label staircase (Fig. 4b) on which the holes are of different depths. Today you can enter the circumstances of the find in appropriate databases.

The collection boxes (Fig. 2) must be dust-tight and stored in a dry place so that the collection does not become fungal and no parasitic wasps , insect mites or museum beetles can enter.

Beetle collections can be structured according to different aspects. For example, they can only include a systematic group, only a limited collection area or only one ecological group, such as species that occur only on carrion .

Documenting and evaluating distribution and frequency

By documenting the sites and the circumstances of the find, data material for various areas of coleopterology is obtained. At the lowest level, faunistics is interested in which beetles occur in a certain limited area. In the transition to animal geography, the geographical distribution of the beetle species is determined. The next step is the question of how this distribution has developed over the course of the earth's history. More fundamental research is being carried out into why the history of dispersal took place one way and not another, when and where a group of beetles came into being and how it has evolved parallel to its geographical spread.

Furthermore, through the spread, for example, ties to certain forage plants, changes in forage plants or, more generally, changes in ecological requirements can be determined. Conversely, changes in the fauna of a certain area can be used to infer climatic changes. In addition, the find data provide direct or indirect ecological information. These in turn help to search for the individual beetle species. Often, ecological knowledge is also helpful in distinguishing between similar species.

Observation of the beetle

The ethology mainly examines partner search, mating behavior, brood care and brood care, sociable beetles, rivalry fights and competitive behavior. In addition to intra-species competition, competition with other animal species is also the subject of research, for example avoiding competition between different ground beetle species that use the same biotope.

Investigation of the beetle

On the one hand, this includes anatomical examinations, which in turn form the basis for other disciplines of entomology. On the other hand, targeted trials and series of trials are set up to test the beetle's food spectrum, behavior or ecological demands.

Further development of the beetle system

In the systematics of the beetles one tries to depict the natural relationships within the beetles as they have developed in the course of evolution . Mainly anatomical features, paleoentomology, ecological demands, behavior, structure and living area of the larvae, molecular genetic studies and distribution maps are used. Because of the longevity of the wing-coverts of the beetles, their occurrence in earlier epochs can be proven relatively easily.

Breeding

The breeding of beetles is pursued on the one hand out of hobby, on the other hand out of scientific interest. The aim of breeding can be the creation of collector's items, for example the creation of new color variants by crossing two Carabus species. Most breeding aims to obtain scientific data. In many cases, eggs and larvae are still unknown. Furthermore, among other things, the number and type of laying of the eggs, the number of larval stages, the duration of the individual development steps, the requirements for the feed and the temperature must be found out. Practical applications can be as diverse as providing individuals for biological pest control, testing plant breeds for pest resistance, treating food as gently as possible for better protection against pests or in zoos the production of food for reptiles.

Protection of the beetle

Coleopterology is by no means in conflict with nature conservation. The investigation of the ecological demands only enables an effective protection of individual beetle species. In addition, conclusions can be drawn about the quality of habitats in general from the presence or absence of conspicuous species and areas worthy of protection can be identified. An example of this is an investigation into the protection of the piston water beetle and the compilation of protective measures for various beetles.

Coleopterology as a hobby

| Fig. 5: Colored wooden relief with 41 insects, including 22 beetles | |

|---|---|

| Top photo of the original, decolorized copy down and beetle with uppercase letters provided A Flying Held Bock B oil beetle C vines Schneider D bull beetle E moon horn beetle F Hirschkäfer G forest Bock H pliers Bock J longicorn K rove L tortoise beetle M Blatthornkäfer N Calosoma O Goldleiste P mourning block Q Sandlaufkäfer R Pillendreher S billy oak T click beetle U paw beetle V piston water beetle W yellow fire beetle Y club beetle |

|

In addition to collecting beetles to create a scientific collection, there is a wide range of possibilities for collecting beetles as a hobby. One often sees showcases in which beautifully colored or bizarre specimens are arranged as a visual attraction. There are also replicas of beetles made of glass, wood, porcelain, metal, raffia, paper, plastic and all conceivable combinations of different materials. They range from a high degree of naturalness to stylized forms and pure ornamentation. Such beetles are used and collected as jewelry, toys, lucky charms or knickknacks . The most common objects are Scarabaeen and ladybirds . Beetles also appear as motifs on pictures, postage stamps, dishes and decorative tiles (Fig. 5 and 6).

Of course you can also make such objects as a hobby. Another hobby is photographing or filming beetles as well as digital processing and alienation of beetle images.

History of coleopterology

The beginnings

We do not know what knowledge was available about the beetles in prehistoric cultures. However, it can be speculated that beetle larvae were known as food in at least some areas and that bizarrely shaped beetles were said to have special properties. The oldest traditional "knowledge" about beetles are the observations made by members of the priestly caste in ancient Egypt on Scarabaeus . The observations related to the structure, behavior and reproduction of the animal, but were sometimes misinterpreted. The beetle was not the object of objective observation, but rather religious worship. The Scarabaeus was seen as an animal god. It is still popular today as a knick- knack or is worn as jewelry or even as an amulet (Fig. 6).

Coleopterology, as it is practiced worldwide as a branch of modern natural sciences, clearly goes back to Aristotle . Of course, coleopterology was initially inseparable from zoology and later part of entomology . Only when the knowledge increased sufficiently could coleopterology establish itself as a branch of entomology.

The organizing spirit of Aristotle stopped in his work Περὶ Τὰ Ζῷα Ἱστορία (Peri ta zoa historia, Historia Animalium , Tierkunde) around 350 BC. BC established what was believed to be known about animals in his time. In the first book, Aristotle expands the diversity of animals in front of the reader and shows possibilities of order. He differentiates, for example, land and water animals, sociable and solitary animals or predators and herbivores. In the fifth part of the first book he states that among the flying animals the bloodless animals have membranous wings. He thus differentiates the flying insects from the birds and bats. Among the flying insects he mentions those whose wings are hidden under a scabbard ( Greek κολεο koleo: case, quiver, scabbard, leather armor of the Greek soldiers), and calls them Coleoptera.

In the fourth book, Aristotle deals with (in his opinion) bloodless animals. He divides them into four groups and counts the Coleoptera in the fourth group, the entoma or insects ( Greek εν-τόμα, en-toma = Latin in-secta = cut into). He understands this to mean the animals distinguished by the incisions in the outer shell, which in modern terminology include arthropods , echinoderms and annelids .

In the fifth book, Aristotle summarizes the views on the reproduction of animals. In part 19 he deals with the insects. The following information is provided with regard to individual beetles.

- The attelabus (a leaf roller) arises from its peers (i.e. through sexual reproduction).

- The stag beetle arises from larvae that live in dry wood. The larvae solidify before their shell cracks open and the beetle hatches.

- The "cockchafer" arises from a larva that spontaneously forms in cow or donkey shit.

- The Scarabaeus rolls balls of dung, hibernates in them and gives birth to small larvae, from which new beetles emerge

- The cantharis arises from caterpillars that live on the fig tree, pear tree or pine. The Cantharis likes to look for stinking substances because it was created from them.

- From a particularly large, horned and unusually built larva, first a caterpillar emerges, then a cocoon, then the necydalus . The cocoon can be made into threads. (Presumably not the beetle wasp wasp Necydalis meant, but a kind of silkworm.)

In other places Aristotle mentions that beetles do not have stings (1st book) and that they belong to the animals that molt (8th book, part 17).

With his revolutionary approach of organizing animals according to anatomical characteristics and finding a system of animals, Aristotle also created a double problem with the beetle. On the one hand, his definition of Coleoptera includes not only beetles, but all insects whose reinforced front wings cover the hind wings. It therefore remains unclear which insects belong to the Coleoptera. On the other hand, through the thesis that some beetles reproduce sexually, others arise spontaneously from rubbish, the view that the beetles form a natural unit.

From Aristotle to Linnaeus

More than four hundred years after Aristotle, Pliny defines the Coleoptera like Aristotle in his natural history ( Naturalis historia ) in the 34th chapter of the eleventh book. In particular, he explains that the particularly delicate wings are covered by a sheath or shell for protection. In particular, Pliny mentions the stag beetle, which is hung around the neck of children as protection against certain diseases, and the backward-moving pill-turner, which rolls the dung into large balls. The maggot-like offspring are deposited in these dung balls and spend the winter protected like in a nest. Then a “beetle” (singing cicada?) Flying with a loud noise is mentioned, as well as a “beetle” that is noticeable at night by loud chirping (cricket?). This is followed by the firefly with information about the time of year it can be found, as well as a black beetle seeking darkness, which arises from the water vapor in baths ( blaps ?). Finally, a gold-colored beetle is mentioned, which fills a kind of poisonous honey into a honeycomb and cannot live in a very specific place in Thrace (cockroach with an egg packet?).

How limited knowledge about insects remains or even decreases with interest in them is also clear from the handwriting of Albertus Magnus , who came from southern Germany . Around twelve hundred years after Pliny, in his De Animalibus (on the animals) in the first book , he follows Aristotle's definition of Coleoptera. However, Albertus Magnus notes critically in his sixteenth book in the 48th essay that the animals named bloodless have a different body fluid instead of blood. He also mentions that there are stinging and sucking mouthparts and that insects (in the Aristotelian sense) fall into three groups, those without legs, those with many legs, and those with legs and wings. He numbers 49 small animals in alphabetical order, resulting in a colorful array of amphibians, reptiles, insects, worms, and snails. There are only two beetles in the narrower sense. Number 13 describes cantarides ( Spanish fly ) with seasonal appearance, behavior and medicinal benefits. And under the number 37, Stupestris is described as a beetle-like worm that hides under the grass and, if it is eaten by cattle , destroys their entrails ( Mayworm ?).

This is also reflected in the beetle science according to Aristotle into the late Middle Ages, which applies to all natural science. On the one hand, Aristotle's errors are not corrected. Rather, he is recognized as an authority in such a way that his views are sufficient as evidence that contrary views cannot be true. On the other hand, knowledge within Europe is internationalized through the Latin language of scholars and a culture of quoting, arguing and debating is developed, which forms the basis for the future development of the natural sciences.

| Fig. 8: Improving the quality of insect imaging | ||

|

|

|

| Fig. 8a: 1646 Wenzel Hollar: Muscarum Scarabeorum ... (Various figures of flies, beetles ...) | Fig.8b: 1705 Sibylle Merian : Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname ) |

Fig. 8c: 1741 August Johann Rösel von Rosenhof: The insect amusement, 2nd part monthly insect amusement |

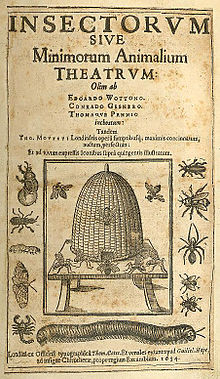

A larger number of beetle descriptions can be found for the first time in the Theatrum Insectorum by Muffet (cover picture Fig. 7). From 1551 the Swiss Conrad Gessner published - in printed form - the contemporary "knowledge" about four-legged friends, birds, fish, snakes and scorpions, initially in Latin, later there is also an animal book in German. Gesner died in 1565 before finishing his work. The London doctor Thomas Muffet (Mouffet, Moffett, Movfeti) worked on the insects (group of animals in the sense of Aristotle) from his estate . He supplements his own observations, incorporates observations by the Englishman Wotton and also uses a manuscript by the Englishman Penny (Pennio), especially his pictures. The result was not published until thirty years after Muffet's death under the title Insectorum sive minimorum animalium theatrum ( The theater of insects or smaller animals ) in 1634. Following on from the butterflies, Muffet treats the Coleoptera in the broader sense and begins in the chap. 15. under the heading Cicindela with the fireflies. A full page is devoted to name explanation and listing of names in different languages and regions. Eight German dialect names alone are listed, the best known of which is Johanniskäfer . The sexual dimorphism is emphasized and the entire literature on the beetle is presumably cited. Non-European forms that glow in other parts of the body are also described. In chap. 16 the locusts, in chap. 17 the cicadas and crickets treated. Cape. 18 is overwritten by de Blattis ( from the cockroaches ). These are characterized by Muffet as similar to the beetles, but without elytra . In the same chapter Muffet describes in the dead beetle ( Blaps ) and borders it in construction and behavior towards the scraping off. Cape. 19 is dedicated to the Buprestis . In the introduction it is stated that there are many different spellings for the word and that the only thing known about the beetle is that it destroys the innards of the cattle if they are eaten by them. Quaddler can be found under German local expressions. Muffet now treats several beetles that he got to know as Buprestis . These include various Carabus species, but obviously also completely different beetles (deduced from the images). The common thing seems to be the excretion of digestive juices that cause wheals . Muffet lists the harmful effects and medicinal uses of this juice according to various authors. In Chapter 20 about Cantharids, the Spanish fly (beetle species) and its use in medicinal formulations (including love potion and poison) is described at the beginning , then Muffet delimits four smaller similar beetle species, which all arise as Cantharids from dry and moist putrefactive substances, but not be used medically. Chapter 21 deals with the typical beetles under the heading Scarabaeus . Individual beetles are described after general remarks on structure, sex difference, reproduction and behavior. Muffet begins with the male stag beetle, then suspects that a smaller stag beetle is its female, and mentions two smaller stag beetles ( barbed stag beetle ? And with picture tiger beetle ?). It differentiates several smaller horned beetle species from one another. This is followed by the description of the oak buck and twelve other longhorn beetles. The bull beetle and four species of rhinoceros beetle are then described (including a species from India, the rhinoceros beetle and the moonhorn beetle ). The pill-turner is dealt with in detail, and there should only be males of it. Another dung beetle is briefly mentioned. The following are very vague descriptions of the rose beetles and cockchafer. Only the walker is described in more detail again. Chapter 22 is about De Scarabaeis minoribus (of the smaller beetles). These are monochrome or patterned and can be classified according to the color and type of pattern. Some species of beetles can be easily identified in the accompanying drawings, but there are clearly also fire bugs. The chapter is only one page long, making it by far the shortest. In chap. 23 the oil beetle ( Meloe ) is described in detail with its seasonal occurrence and habitat, its copulatory attitude is mentioned and its medical use is explained. The treatment of the beetles concludes with some very vague remarks about water beetles. The following chapters no longer refer to beetles in the modern sense.

The Italian doctor Aldrovandus also benefits from the fact that Gesner no longer comes to publish the insects. Aldrovandus is particularly keen on insects. His work De animalibus insectis (of the incised animals) was published much earlier than Theatrum Insectorum , but was created around the same time and is in parts more progressive. In 1602 (Muffet dies 1604) Aldrovandus separates the "incised animals" into land and water animals, and sorts them according to the number of legs as well as existence and type of wings. He thus prepares the division of insects in the broader sense into annelid worms (without legs), insects in today's sense (hexapods, six-legged animals), spiders (with eight legs), crabs (with 10 or more legs) and millipedes. In addition, he divides the flying insects according to the different structures of the wings. In De animalibus insectis , 300 pages are devoted to insects. Section I deals with bees, wasps and hornets, Section II with butterflies and dragonflies, Section III with the two-winged species, Section IV with Coleoptera in the broader sense, and the last section with wingless insects. As Coleoptera or Vaginipennes (part of the beetle) Aldrovandus included Locusta (grasshopper), Gryllus (cricket), Scarabaeus (part of the beetle), Cantharis (part of the beetle), Ips, Buprestis (part of the beetle), Coccoius, Cicindela (firefly) and Blatta (Cockroach) together. He sets these as covered-winged (alas opertas = covered, hidden wings) opposite the other flying insects (Alas detectas = open, unprotected wings), the flying insects are counted together with the wingless as land animals with legs. The fourth book describes the Coleoptera. A chapter is dedicated to each of the animals mentioned above. In principle, each chapter is divided into sub-chapters, which explain the name, point out doubtful things, list synonyms, show the differences between the individual species and clarify with colored pictures, deal with nutrition, reproduction and the material from which the animals are made arise, state, name the character of the animal and its behavior, mention fables, proverbs or doctrinal slogans, show the medical and other uses and cite traditional material.

In Chapter 3 (p. 444) the Scarabaen are described as the Coleoptera with a hard shell and very fine wings. It should be noted that the demarcation to Cantharis is unclear. 47 species are shown. When reproducing, the diversity of the origin material is pointed out. It is also mentioned that some beetles reproduce sexually and that the pill-twister only occurs as males. Its special properties, for example its use as an oracle , are discussed in detail. In Chapter 4 (p. 469) about Cantharis, the illustration of the 47 species shows that they are beetles with softer wings. In Chapter 5 (p. 486) it is explained that the Ips is only known from literature, and no picture is attached. Chapter 6 (p. 487) mentions that the Buprestis is oily and kills cattle. Three different species are shown, which are not typical female oil beetles, but can be males. The sub-chapter on medical significance is extensive. Cape. 7 (p. 491) is again short and without illustration. It is said to be an animal that is rare in Italy and resembles the firefly. Chapter 8 (p. 492) is about the firefly and has a subsection on the nature of the light this beetle produces. In summary, however, it must be emphasized that the main part of the much information about the insects consists of citing what older sources say about the animals.

In 1646 copperplate engravings by Wenceslaus Hollar (Fig. 8a) appear under the title Diversae Insectorum aligerorum Vermiumque etc. figurae ad Natruam delineatae a Wenceslao Hollar, Bohemo (Various pictures of winged insects, maggots etc. drawn from nature by Wenceslaus Hollar from Bohemia). From 1675 to 1705, the illustrated books by Maria Sibylla Merian , daughter of Hollar's teacher, Matthäus Merian, followed . The panels in The caterpillar's miraculous transformation and peculiar flower food (three volumes) are still black and white like the plates by Hollar, the illustrations for Die European Insects (De Europische Insecten, 3 volumes), and the Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (Fig. 8b) are colored. The text on the page that follows the title page of Merian's Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium is symptomatic : This metamorphosis of the insects of Surinam is presented by Maria Sibylla Merian to all lovers and investigators of nature . Johann Roesl vom Rosenhof follows the same tradition . From 1741 he published the monthly insect amusements , valuable copperplate engravings and texts with new knowledge. The second volume deals with the beetles (Fig. 8c). The works of these artists demonstrate a new approach to nature that is paired with precise observation. At the same time, the appearance of these works increases the trend towards observing nature, observing nature and observing nature. The quality of the images is getting better and better.

| Cladogram No. 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Key to the beetle according to Lister |

The English doctor and zoologist Martin Lister was the first to no longer simply line up the beetles one after the other, but to classify the Coleoptera, which were known in England at the time (cladogram No. 1). It separates land and water beetles on the first level. After the antennae have been built, he divides the land beetles into those whose antennae a) end in lamellar form, b) are hair-shaped or pointed, c) are guided on a snout (proboscis), and d) the bugs provided with a proboscis. Point b) is further subdivided according to more complete or stunted elytra. Those with complete elytres are again subdivided into five groups according to conspicuous features, such as speed. In point c), a distinction is made between whether the feelers are at the tip or in the middle of the trunk. The water beetles are classified according to whether they can be found in fresh or salt water. If today the further classification of the land beetles with pointed antennae ends and complete elytra also makes you smile, it must be emphasized that this is the first time that a primitive identification key for the beetles is available. However, this classification was not published until 1710 as an appendix to the work by Ray presented below.

In 1668, the Italian Francesco Redi refuted the spontaneous generation claimed since Aristotle . The conclusions he draws from his experiments are not absolutely necessary for tiny animals such as the as yet undiscovered bacteria , but for the beetles one could conclude: where no eggs are laid, there are no beetle larvae. In doing so, Redi not only deprived the Scarabaeus of its ability to father offspring without a female, and he not only overturned the belief in spontaneous generation. Rather, it made the concept of the biological species as a reproductive community, which was formulated much later, possible in the first place .

The Dutchman Swammerdam considerably expands knowledge of insects through microscopic examinations. However, it is indirectly important for the development of coleopterology for another reason. In the traditional view, the larva dies and the imago emerges again. From a philosophical-religious perspective, Swammerdam changes this way of looking at things. Each stage of development is only a further development of the previous stage and is already set up in the previous stage ( preformation theory ). The butterfly is already hidden in the caterpillar. Under the new perspective, Swammerdam recognizes the difference between a simple moult and a real step of transformation and states that there are different types of transformation.

The Englishman John Ray (Joannes Raius) builds on this approach of different types of development and divides the insects into those without metamorphosis, those with half-complete metamorphosis (Metamorphosis semicompleta), those with incomplete or hidden metamorphosis (Metamorphosis incompleta vel opecta) and those with barrel dolls ( Metamorphosis coarctata). In the introduction to Rays Historia Insectorum , the beetles are placed in the third group, i.e. to the insects that transform from a larva into a pupa and from this into a flying insect. Within this group, the Coleoptera = Scarabaei are compared as the first group with the other insects without elytra (Anelytra), the latter are further broken down below (cladogram no. 2). This means that bugs, crickets, grasshoppers and earwigs are no longer part of the Coleoptera because of their incomplete metamorphosis. Ray also developed the concept of biological species based on the idea.

| Cladogram No. 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Classification of the beetles according to Ray |

However, in Ray's Historia Insectorum , which did not appear until 1710, the beetles are still confusing. A total of almost 240 species are described according to physical characteristics and divided into four sections, the largest of which is divided into 14 sections. In the first section, a count begins under the heading Scarabaei or Cantharidae , which runs intermittently from 1 to 37. Then under the heading semicircular or hemispherical Scarabaeen a new counting from 1. – 13 begins . as well as a second count from 1-3. This is followed by the 14 sections defined after the sensor was built, in which the counting starts anew in each section. The beetles are closed off with a short-winged bird (Staphylinus major totus niger, large, completely black short-winged bird).

Linnaeus and immediate consequences

It was in the air that given the abundance of different insects and the difficulty of a clear description, at least a clear name had to be created. It would be advantageous if this naming would also group similar animals together. The Swede Linnaeus (Linnaeus) also encountered this need.

Uppsala University lost its collection of plants from Lapland in a fire in 1702. At the insistence of the king, Linnaeus, a capable student who was poorly paid, was finally commissioned to procure replacement material. So he traveled to Lapland in 1732. When classifying his collection material in the herbarium , he was faced with the task of bringing order to the abundance of plants. He came up with the idea of introducing mandatory double names ( binomial nomenclature ). The generic name above summarizes similar plants or animals to form one genus , the following species name, the specific epithet , uses one word to designate a feature that distinguishes the species from the other species of the genus. In the first edition of Linnés Systema Natura from 1735, the insects were divided into seven orders, the order Coleoptera (including cockroach, cricket, grasshopper and earwig) was broken down into 23 genera. There were further editions in quick succession, the tenth edition from 1758 being considered the most important (title page Fig. 10). In the second volume of this edition 584 species of beetles (in the narrower sense) are pressed into the genera No. 170 Scarabaeus to No. 191 Staphylinus . The genera are divided into four groups according to the structure of their antennae. Earwig, cockroach and cricket follow. For each genus it is indicated where the larvae can be found.

In the 12th edition of 1767 the number of beetle genera (in the narrower sense) had already increased from 22 to 29, and the number of species had also increased significantly. For example, the number of species in the genus Scarabaeus had grown from 63 to 94 species, seven of which were placed in the new genus Lucanus . In the genus Silpha the number of species had increased from 26 to 35, in the genus Cassida from 18 to 31. The genus Dermestes , which contained all beetles that attack animal substances, furniture or food, was broken down into Dermestes and Ptinus .

An extensive work and a treasure trove for traditional knowledge is the generously laid out entomology, ou Histoire naturelle des insects (entomology or natural history of insects) by the French nobleman Olivier . The eight volumes on the beetles appear between 1789 and 1808. They present 100 genres numbered consecutively, with quite a few already (without a new number) split into two genres. Each genus contains a short Latin and next to it a French, but the two are not always congruent. This is followed by a French description, often several pages, with further information on the genus and the species, and there is at least one exact colored engraving for each genus. After the first three volumes have appeared, the German Illiger will translate them into German with commentary. The demarcation of beetles from other insects corresponds to that of today.

Scientists specializing in entomology were of course more familiar with the matter than the botanist Linnaeus. The Dane Fabricius was a student of Linnaeus. Fabricius paid special attention to the insects' mouthparts and put the beetles to the orders with biting mouthparts. Within the Coleoptera in the broader sense, he set the beetles in the narrower sense as Eleuterata (from ancient Greek ελεύτερα eleutera, free because the jaws are not covered by a sheath, but are exposed) from the Ulonota (cockroaches, grasshoppers, earwigs) and arranged them like Linnaeus after the feelers were built, but with more subdivisions than Linnaeus. From 1792 to 1794 he published the Entomologia systematica in four volumes .

Olivier is a patron of the French Pierre André Latreille . This student of Fabricius organized his collections and finally separated crickets and grasshoppers from the Coleoptera. He introduces the family between order and genus. When arranging the collections of Fabricius, he divided the beetles into 148 genera in 1796. The classification of the beetles based on the construction of the tarsi also goes back to Latreille. The Latreille tarsal system, which is already used by Olivier, classifies the beetles into pentamers (five limbs), heteromers (hind legs with four limbs, the others with five), tetramers (four limbs) and trimers (three limbs) according to the number of limbs. .

In an additional volume to the four volumes of Fabricius' Entomologia systematica , the systematics of Fabricius with 117 species of beetles is directly compared to the system of Linnaeus with 29 species, the alphabetically ordered French trivial names are listed with the German equivalents and vice versa. The two genera Blatta (cockroaches) and Forficula (earwigs), which Linné counts to the Coleoptera, are "branded" by an Ul for Ulonota. As a result, Aristotle's bloodless flying animals, whose reinforced front wings protect the hind wings, are finally trimmed back to the insect order Coleoptera in European cooperation.

The need for technical language, requirements for the description of an insect, the different systematic value of individual identifying characteristics, the importance of locally restricted fauna, such problems have now been discussed. The character of such discussions can be seen in the foreword and the detailed introduction to the directory of Prussian beetles from 1797. There it is pointed out, for example, that it makes no sense to assign the females their own number with consecutive numbering.

Classification and subdivision of the Coleoptera

After the beetles were clearly separated from the other insects as a natural unit by the type of metamorphosis and several common anatomical features ( autapomorphies ), a double challenge arose. On the one hand, the beetles wanted to be classified naturally in the insect kingdom; on the other, it was necessary - to use Haeckel's expression - to set up a beetle family tree. The aim of the systematists is to design the system in such a way that it reflects the course of evolution. This task is far from over with the beetles. As an example, the fan-winged beetles are mentioned. In 1793 the first described species was counted among the hymenoptera . In 1808 she was added to the two-winged class . In 1813 they were upgraded to the Strepsiptera order . In 1981 the group was classified as the beetle family. Today the fan-winged species are once again viewed as an order, but it remains a matter of dispute whether this is closer to the two-winged species or closer to the beetles.

Latreille divided the beetles into families in 1802. Some families are so clearly separated from the other beetles by autapomorphism that they can be viewed as a natural unit. Others are reservoirs for genera that do not fit into the other families. Such families are partly split up later by Latreille himself. In 1806 Latreille published a classification into 18 families. (Cicindeletae, Carabici, Hydrocanthari, Sternoxi, Malacodermi, Clerii, Staphylinii, Ptiniores, Palpatores, Necrophagi Byrrhii, Otiophori Hydrophilii, Sphaeridiota, Coprophagi, Geotrupini, Scarabaeides, Lucanides). For the most part, these families are further split up in the following years. Also because the beetles from all over the world including fossil beetles are considered in the following years, many more beetle families are added. All family names today end in -idae. Today there is no fear of assigning a single family to a single species if it is only sufficiently different from the other families.

Latreille not only arranges the beetles vertically, but also layers them horizontally. He shifts the levels section, tribe, familia, stirps between order and genre and, in some cases, another level through Roman numbers. This division is understood as a sign of a God-given fixed order.

The new way of thinking of evolution, set in motion by Darwin in 1859, penetrated entomology through Brauer in 1885. The starting point was the idea that the wingless insects did not necessarily form a single group. From a purely intellectual point of view, it is obvious to assume that winged insects evolved from wingless ones. The latter were referred to as primarily wingless and summarized as apterygogenea (created without wings). It was also conceivable that certain winged insects could evolve into wingless insects. They are then secondarily wingless and were placed in the pterygogenea (which developed with wings). Further evidence of evolution was provided by paleoentomology . Within the winged insects, an original (not foldable back) and a modern, articulated wing type were found. All animals with complete metamorphosis belong to the representatives of the second group, the Neoptera (new winged wings) and form the Holometabola (completely transformed) or Endopterygota (wings develop inside) within the Neoptera. The purely formal military stratification Classis-Legio-Centuria-Cohors-Ordo, as we find it in Latreille, has been replaced by the class insects, subclass flying insects, superordinate new-winged species, intermediate order with complete transformation, order beetles. The step between the holometabola and the order Käfer should certainly be further subdivided.

While the systematics, which is based only on anatomy, places the beetles in the vicinity of other insect groups with hardened forewings (grasshoppers, cockroaches, praying mantis, bedbugs, earwigs), the systematics, which is based on the idea of evolution, comes to different results. The various theories of how the incomplete metamorphosis developed into the complete metamorphosis agree that the complete metamorphosis is younger than the incomplete one. This removes the beetles from grasshoppers, bedbugs, etc. The paleoentomology provides a fossil find in 1944 ( Tshekardocoleus ), which is classified between primitive beetles and primitive mudflies on the basis of the veining of the wings . This suggests that mudflies and beetles are sister groups . However, there are also indications that point to the great-winged or net-winged as a sister group. Neither chromosome examinations nor fossil finds have so far been able to convincingly answer the question of the beetles' closest relatives.

In 1903, Ganglbauer separated the beetles into Polyphaga and Adephaga after veining the wings . According to unanimous opinion today, the ancestors of the beetles, the Protocoleoptera, split into Archostemata , Myxophaga , Adephaga and Polyphaga . According to Crowson , Polyphaga and Myxophage are sister groups, the Adephaga and even earlier the Archostemata separated (cladogram no. 3), according to molecular studies, however, the Myxophaga are a sister group to Adephaga and Polyphaga.

| Cladogram No. 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systematics of the beetles according to Crowson |

The establishment of coleopterology

A second thread in the history of coleopterology ties in with Linnaeus with his 584 species of beetle. The number of beetles described and the interest in them is growing rapidly. Around 1795 David Heinrich Hoppe collected almost 600 species from 81 genera in the vicinity of Erlangen, in the Catalogus Coleopterorum Europase, Caucasi et Armeniae Rossicae (title page Fig. 1) there are well over 3000 species in the 1906 second edition (albeit with synonyms) In 1868 the world catalog by Gemminger and Harold counted 77,000 species, the 31-volume world catalog by Junk und Schenkling , published between 1910 and 1940, contains 221,480 species, around 1950 around 350,000 species were known. The Russian Entomological Society, founded in 1860, published a list of 3,124 species in 1932, in 1935 the list already comprised 18,000 wood beetle species, and in 1945 it had grown to 23,000 species.

At first, beetles were only mentioned in passing in publications about animals, then a part of books on insects, but the increasing interest coupled with the increasing number of known species meant that books were soon published that deal exclusively with beetles. Among the scientific works in German-speaking countries, the first volume by Erichson appeared in 1837 : Die Käfer der Mark Brandenburg . The species are classified according to a large number of characteristics (antennae, number of tarsus, number of visible abdominal segments, position of the spiracles, deflection of the front hips ...)

Erichson did not finish his work. However, his system was adopted in a more refined form by the Austrian Ludwig Redtenbacher . Redtenbacher used Stephans: Manual of British Coleoptera (London 1839) for the family key and in 1849 published Fauna austriaca, the beetles , which appeared in three editions. The 2nd edition was published in 1858 and contains 1138 genera in 67 families. In this work, the description of the external parts and organs in the introduction took up 29 paragraphs and almost 13 pages. The introduction was followed by a table to determine the families, another to determine the genera and in the main part a key to the species. The species were provided with information about their habitat. The work was completed with two panels with anatomical details.

From 1858 Calwers Käferbuch appeared in several editions. It is smaller in size, but is characterized by 48 color plates depicting over 1000 species of beetles. The second edition in 1868 was supplemented by Jäger with comments on the location and way of life. In addition, the identification tables for families from Redtenbacher have been adopted in a modified form. For each genus, additional European species with country of origin are named as an appendix.

From 1892 Ganglbauer appeared : Die Käfer von Mitteleuropa . Of the seven-volume work, only four have been completed. In the foreword, Ganglbauer mentioned that he took particularly important larval forms into account for natural classification . 55 woodcuts are included in the text of the first volume. Behind each type is not only the author, but also the font in which the first description can be found, as well as the texts of other descriptions of the same type.

Reitter appeared between 1908 and 1916 : Fauna Germanica, the beetles of the German Empire in five volumes. Based on Ganglbauer, the "analytical tables" are divided into department, family series, family, subfamily, tribe, genus, subgenus and species. For each species, remarks about the way of life and distribution were noted. Color tables are attached to each volume. The total of 168 panels are of high quality and depict the majority of the types and details described. The work includes all Central European Beetles and is distributed internationally.

In 1965 the eleven-volume reference work Freude-Harde-Lohse: Die Käfer Mitteleuropas began with an introductory volume and was completed in 1998 with the publication of the fourth supplementary volume . It contains an outline drawing for each genus, and the identification keys have been supplemented with numerous detailed drawings. The families are numbered, the genera are within each family and the species are numbered within the genera. Each species can be assigned a unique code number, which is made up of the family, genus and species number.

In keeping with the new technical possibilities and the spirit of the times, Arved Lompe started a Beetle Europe document , which is accessible on the Internet free of charge and without registration, based on the works of Reitter and Freude-Harde-Lohse , which is still under construction. With Europe, it covers an area that is much more species-rich than Central Europe and the length of the identification keys has therefore increased considerably. One of the great advantages is that the website can be updated at any time, and the identification keys are much easier to use thanks to clickable, partly colored drawings, photos, microscopic or electron microscopic images.

In the meantime, the knowledge has grown so that not only books about the beetles, but also books about parts of coleopterology appear.

The fauna of the beetle has been significantly further developed by Horion . Based on a comparison of the occurrence of beetles in the German provinces, he found stereotypical distribution patterns and published a twelve-volume work on the Faunistics of Central European Beetles between 1941 and 1974 . Today the distribution maps of the species are explained by geographically and climatically conditioned distribution paths from refuges during the Ice Age. Cold-loving beetles spread along the mountain ranges, for heat-loving beetles mountains are more of an obstacle to expansion. Today you can report beetle finds on various websites or, as a registered user, enter them yourself. For example, the Working Group of Southwest German Coleopterologists has created a page for each profile of a species with the location of the sites within Baden-Württemberg, on which information is requested to be found.

Joy-Harde-Lohse has meanwhile been expanded to include six volumes, The Larvae of Beetles of Central Europe and eight volumes, E1-E8, on the ecology of beetles, as well as a catalog volume for a complete work on the beetles of Central Europe. In 1977 Thiele published a book with over 350 pages just about the choice of habitat for ground beetles.

In addition to these more science-oriented books, popular science books are increasingly appearing. The natural history of the animal kingdom for school and home , Brehm's animal life , the Schmeil (from 1899), which found its way into higher education institutions and is still used today, and the long series of identification books, started in 1954 with the Kosmos nature guide, are representative examples Which beetle is that . The book by the coleopterologist and writer Ernst Jünger Subtile Hunt should also be mentioned here. Because of their bizarre shape and the often striking colors, the beetles are the subject of elaborate illustrated books. There are numerous forums and galleries on the Internet, such as the Beetle Gallery .

Working groups

Many coleopterologists are organized regionally so that they can carry out joint activities and exchange their observations. Even laypeople or beginners are welcome at their events. Some addresses are

- Hessian coleopterologists

- Working group of Rhenish coleopterologists

- Working Group of Southwest German Coleopterologists

- Working group of Westphalian coleopterologists

- Coleopterology Community

- Vienna Coleopterologists Association

Famous coleopterologists

- Edmund Reitter : His identification keys and colored plates of high quality in the five-volume work Die Käfer des Deutschen Reiches (1908) made knowledge about the beetles accessible to a wide audience for the first time.

- Adolf Horion : He collected all publications and private communications about the occurrence and way of life of the Central European beetles, evaluated them and published them in 12 volumes of his Faunistics of the Central European Beetles .

- Karl E. Schedl : The forest entomologist gained international fame as one of the leading specialists in bark beetles and built up one of the most important collections of bark beetles in the world.

Today the knowledge of the beetles has expanded so much that most coleopterologists specialize in a small systematic group of beetles, e.g. B. on a single genus.

literature

- Edmund Reitter: Fauna Germanica. The beetles of the German Empire. Lutz, Stuttgart 1908-1917, DNB 560823134 . (5 volumes with colored plates)

- Adolf Horion (1941–1974): Faunistics of the Central European Beetles. (12 volumes)

- Heinz Joy , Karl Wilhelm Harde , Gustav Adolf Lohse : The beetles of Central Europe. Goecke & Evers, Krefeld 1964–1983, ISBN 3-334-61035-7 . (Volume 1–11) - (volumes followed later with additions, larvae and ecology; a total of 15 volumes are available)

Richly illustrated and recommended for beginners:

- Karl Wilhelm Harde, Frantisek Severa: The Kosmos-Käferführer. Franckh, Stuttgart 1981, ISBN 3-440-04881-0 .

- Wolfgang Willner: Pocket dictionary of the beetles of Central Europe. Quelle & Meier, Wiebelsheim 2013, ISBN 978-3-494-01451-7 .

Web links

- Page on the methodology of insect collecting in Commons

- Commons: Category: Insect collecting

- Frank Koehler's Beetle Gallery

- Determination of the beetles of Europe

Individual evidence

- ^ Adolf Horion : Käferkunde for nature lovers . Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1949.

- ↑ a b Heinz Freude , Karl Wilhelm Harde , Gustav Adolf Lohse (ed.): Die Käfer Mitteleuropas (= Käfer Mitteleuropas . Volume 1 : Introduction to Beetle Science ). 1st edition. Goecke & Evers, Krefeld 1965, ISBN 3-8274-0675-7 .

- ↑ Pictures of egg, larva, pupa and various stages of coloration of the newly hatched imago on a French forum page ( Memento from December 9, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Lars Hendrick, Michael Balke: On the occurrence of the piston water beetles ... in Berlin .... Berlin nature conservation papers Protection piston water beetles ( Memento from October 7, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF, 36 kB)

- ^ Species handbook of the Bavarian Forest Administration. Käfer, p. 59 ff. ( Memento from May 21, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.6 MB)

- ↑ a b c d Juri Dmitrijew: Man and Animal. From d. Soot. by Thea-Marianne Bobrowski. Raduga publishing house. Moscow 1988, ISBN 5-05-001914-1 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Josef R. Winkler: Pocket Atlas of the Beetles Dausien, Hanau am Main, 2nd edition 1975, p. 2494.

- ↑ Aristotle: Historia Animalium 1st book 350 BC. Chr. Classics.mit.edu

- ↑ Aristotle: Historia Animalium 4th book 350 BC. Chr. Classics.mit.edu

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Gillott (Ed.): Entomology. 3. Edition. Springer, ISBN 1-4020-3182-3 .

- ↑ Sigmund Schenkling: Explanation of the scientific beetle names (genus)

- ↑ W. T. M Forbes: The Silkworm of Aristotle. Classical Philology, Vol. 25, No. 1 (Jan. 1930), pp. 22-26 as html

- ↑ Aristotle: Historia Animalium 5th book 350 BC. Chr. Classics.mit.edu

- ↑ a b Bernhard Klausnitzer: Wonderful world of the beetles . Herder Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau / Basel / Vienna 1982, ISBN 3-451-19630-1 .

- ↑ Pliny the Elder: Naturalis historia 11th book on insects, chap. 34 English translation Latin edition

- ^ Albertus Magnus: De animalibus English search engine for Albertus Magnus, provides Latin text

- ↑ Tho. Movfeti: Insectorum sive minimorum animalium theatrum olim from Edoardo Wottono, Conrado Gesnero, Thomaque Pennio inchoatum T. Cotes, London 1634 View cover picture and two pages ( Memento from August 25, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) e-book

- ^ Charles E. Raven: English Naturalists from Neckam to Ray Chap. X: Thomas Mouffet and the Theatrum Insectorum e-Book

- ^ A b Frank N. Egerton: A History of the Ecological Sciences. Part 12: Invertebrate Zoology and Parasitology during the 1500s. esa, the Bulletin of the ecological Society of America, Vol. 85, No. 1, January 2004 Internet edition

- ↑ Ulisse Aldrovandi: De animalibus insectis libri septem ... Bolognia 1602. Internet edition

- ↑ Wenceslas Hollar: Diversae insectorum aligerorum, vermimque etc. ad naturam delineatae a Wenceslao Hollar Bohemo. Antwerp 1646. Pictures in Wikimedia Commons

- ↑ Maria Sibylla Countess Matthaei Merian's parents Seel. Daughter: The caterpillars wonderful transformation and strange flower food . 2nd part 1683

- ^ Maria Sibilla Merian: De Europische Insecten. Amsterdam 1780

- ↑ a b Maria Sibylla Merian: Ofte Verandering der Surinaamsche Insecten ( Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium ) Amsterdam 1705, Piron, London 1980–1982 (reprint), Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1992 (reprint), ISBN 3-458-16171-6

- ↑ M. Lister: Appendix de Scarabaeis Bretannicis. In: Joannes Raius: Historia Insectorum. Churchill, London 1710 digitized copy

- ↑ Francesco Redi "Esperienze intorno alla generazione degl'insett" Firenze 1668. it.wikisource

- ↑ James Duncan: Beetles, British and Foreign. David Bogue, London.

- ↑ a b Joannes Raius: Historia Insectorum. Opus posthumum London Churchill 1710 digitized copy

- ↑ Caroli Linnei, Sveci, Doctoris Medicinae systema naturae ... : Historia Insectorum 1,737 digitized copy

- ↑ a b c Luc Auber: Coléoptères de France. Fascicule I Edition N. Boubée & Cie, Paris 1955.

- ↑ Caroli Linnei, ... systema naturae ... 1758 digitized copy

- ^ Caroli a Linné: Systema naturae ... Editio 12 reformata, Holmiae 1767 digitized copy

- ↑ Olivier: Entomologie, ou Histoire naturelle des insects. Coleoptéres volume 1–8 first volume second volume third volume fourth volume fifth volume sixth volume eighth volume

- ↑ Carl Illiger: Olivier's Entomology or Natural History of Insects, ... .. Beetles. K. Reichardt, 1800. books.google.de

- ↑ Latreille: Précis des caractères générique des insectes disposés dans un ordre naturel F. Bourdeaux, 1796 as PDF

- ^ A b Edmund Reitter : Fauna Germanica, the beetles of the German Empire. Volume I, KG Lutz 'Verlag, Stuttgart 1908.

- ↑ P. Movfeti et at .: Epitome entomologiae Fabricianae sive nomenclator entomologicvs emendatvs. Gottlob Feind, Leipzig 1797. in the internet archive

- ↑ Illiger: Directory of beetles in Prussia. Braunschweig 1797. as an e-book

- ↑ a b PA Latreille: Genera crustaceorum et insectorrum secundum ordinem ... Koenig, Paris 1806. at BHL

- ↑ a b Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 3, Thomson Gale, ISBN 0-7876-5779-4 .

- ↑ Ludwig Ganglbauer: Systematic-coleopterological studies. Munich Coleopterological Journal 1st volume 1903. all four volumes at BHL

- ^ David Heinrich Hoppe: Enumeratio Insectorum Elytratorum cricam Erlangam indegenarum. Typis Hilpertianis, 1795 on Google Google-book

- ↑ L. v. Heyden, E. Reit (t) er, J. Weise: Catalogus Coleopterorum Europae, Caucasi et Armeniae Rossica. Editio secunda, Berlin 1906.

- ↑ Urania animal kingdom. Volume 2, Rowohlt, 1974, ISBN 3-499-28011-6 .

- ↑ Wilh. Ferd. Erichson: The beetles of the Mark Brandenburg. 1st volume, Berlin 1837 digitized copy

- ↑ Ludwig Redtenbacher: Fauna austriaca Die Käfer processed according to the analytical method. C. Gerold's Sohn, Vienna 1858, 2nd edition. digitized copy

- ↑ Images on the plates from Calwer's Käferbuch

- ↑ Gustav Jäger (Ed.): CG Calwer’s Käferbuch . 3. Edition. K. Thienemanns, Stuttgart 1876.

- ↑ Scanned 4th edition of Calwer's Käferbuch

- ↑ Ludwig Ganglbauer: The Beetles of Central Europe… Gerold, Vienna 1892–1904. all four volumes at BHL

- ↑ Images from Reitter: Fauna Germanica: Die Käfer des Deutschen Reichs.

- ^ Wilhelm H. Lucht, Bernhard Klausnitzer: Die Käfer Mitteleuropas . Ed .: Heinz Freude (= Käfer Mitteleuropas . Volume 15 ; 4th supplement band). Gustav Fischer / Goecke & Evers, Jena / Krefeld 1998, ISBN 3-437-35366-7 .

- ↑ Determination of the Beetles of Europe on the Internet

- ^ Gustav de Latin: Plan of the zoogeography. Gustav Fischer Verlag, 1967.

- ↑ ARGE SWD Coleopterologists ( Memento from January 15, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ H.-U. Thiele: Carabid Beetles in their Environments: a study on habitat selection by adaptions in physiology and behavior ( ground beetles in their biotope. Habitat selection through physiological and ethological adaptations. ) Springer, Berlin 1977.

- ↑ GH v. Schubert (Ed.): Natural history of the animal kingdom for school and home. Schreiber, Esslingen (3rd edition 1886)

- ↑ Alfred Edmund Brehm: insects, millipedes and spiders, Brehms animal life. Volume 9 1892 at caliban

- ↑ Otto Schmeil (and successor): Schmeils Biological Educational Work: Tierkunde.

- ↑ Jan Bechye: Which beetle is that? Franckh, Stuttgart 1954, DNB 450290085 .

- ↑ Ernst Jünger: Subtile Hunts. Klett, 1967.

- ↑ Frank Köhler's Beetle Gallery