Kondratiev cycle

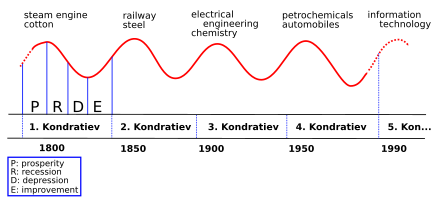

The Kondratjew cycles (older transcription: Kondratieff cycles ) describe the core of a theory of cyclical economic development developed by the Soviet economist Nikolai Kondratjew , the theory of long waves . The starting point for the Long Waves are paradigm shifts and the associated innovation- induced investments : There is massive investment in new technologies and thus an upturn. After innovation becomes widespread, the associated investments are drastically reduced and there is a downturn. In the period of the downturn, however, a new paradigm is already being worked on.

development

In 1926 Kondratiev published his essay The Long Waves of the Economy in the Berlin journal Archive for Social Science and Social Policy . Using empirical material from Germany, France, England and the USA, he found that the short business cycles (see also the pig cycle) are overlaid by long business cycles. These long waves, which last 40 to 60 years, consist of a longer ascent phase and a slightly shorter descent phase. The bottom is reached after an average of 52 years.

At that time, Kondratiev was able to determine two and a half such long waves, assuming that the third wave would be drawing to a close at the end of the 1920s, which also happened with the stock market collapse and the global economic crisis . He sees the cause of these long waves in the laws of capitalism , while new technologies are not the causes but the consequences of the long waves.

The characteristics of the individual waves are that in the upswing the years with a good economy predominate and in the downswing - when there is an overhang of recession years - mostly important discoveries and inventions, so-called basic innovations, are made. These always occur when a deficiency or a need that can no longer be satisfied due to a further increase in productivity has arisen.

The establishment of the European railways was therefore decisively advanced because the previously available means of transport (horse-drawn carts on country roads and the like) were no longer able to adequately distribute the already industrially produced goods on the markets.

Joseph Schumpeter

In 1939, in his work on business cycles, Joseph Schumpeter coined the term Kondratiev cycles for these long business cycles and pointed out that the basis for these long waves are fundamental technical innovations that lead to a revolution in production and organization . For this he coined the term basic innovations , leaving open what led to their emergence and thus to a new Kondratiev cycle. For him, it was not the discovery of a basic innovation that was decisive, but its broad application.

Further

Recently, among others, Leo Nefiodow and Erik Händeler as well as internationally Christopher Freeman and Carlota Pérez have dealt with the Kondratiev cycles. The focus is often on working out a current fifth and a future sixth Kondratiev. The "international" school consists mainly of Neo-Schumpeterians, although not all Neo-Schumpeterians are cycle theorists.

Andrei Korotajew claims in a paper from 2010 to have determined the presence of Kondratiev waves in the global gross domestic product .

Division of economic development into Kondratiev cycles

There is general agreement about the timing of the Kondratjews, albeit with some deviations.

- Period (approx. 1780–1840): early mechanization; Start of industrialization in Germany; Steam engines -Kondratjew . There is speculation that there was an earlier cycle in England.

- Period (approx. 1840–1890): Second industrial revolution of the railroad - Condratiev ( Bessemerstahl and steam ships ). Called the founding period in Central Europe

- Period (approx. 1890-1940): electrical engineering and heavy machinery Kondratiev (also chemistry )

- Period (approx. 1940-1990): single-purpose automation Kondratiev (basic innovations: integrated circuit , nuclear energy , transistor , computer and the automobile )

- Period (from 1990): Information and communication technology Kondratiev (global economic development)

Since the 4th cycle, the “ economic miracle ”, ended in 1990 and the growth rates became smaller, since 1990 an increase in growth rates has become noticeable. The global economic growth with growth rates of 5% from 2004 is just as high as in the times of the economic miracle.

This suggests that 2004 is the beginning of the high period of the 5th cycle. The International Monetary Fund is forecasting growth rates of just under 5 percent for the next five years. This cycle, like the fourth, could bring full employment and accelerated development. As with the other cycles, the world economy could be supplemented and renewed in the next 20 years, there could be breakthroughs in important scientific areas that will benefit mankind.

Various candidates have already been brought into play as technologies that will dominate a possible sixth Kondratiev cycle:

- biotechnology

- nanotechnology

- Robotics or artificial intelligence

- Nuclear fusion energy

- Technology of resource efficiency and regenerative energies , energy saving, energy efficiency

- Psychosocial Health and Competence

- Mobile internet, cloud computing , internet of things

Nefiodow has been advocating the thesis that the next basic innovation lies in the health sector since 1996. In his book "The Sixth Kondratieff" he takes the view that the competitiveness of companies and economies in the future will increasingly be determined by their health literacy. Handel joined the view and modified it in such a way that production-inhibiting factors such as burnout and internal dismissal must be contained not only preventively and therapeutically through medical and psychological measures, but also through a corporate culture that is more gentle on human resources .

Long Wave Theories

For a long time, attempts have been made to support the Kondratiev cycles with a theory. However, this is extremely difficult, which is why it has not yet been possible to develop a generally applicable and satisfactory theory. One of the reasons could be that the general economic conditions changed too much from the first to the current fifth Kondratiev.

There are four criteria that a long wave theory must meet:

- Causality: Ultimately, innovation must always and exclusively be decisive for the economic upturn.

- Cyclicity: The theory must show that there are cycles of 45 to 60 years.

- Macroeconomic impact: the impact on the economy as a whole does not come from individual innovations, but from the combination of many different innovations across the boundaries of economic sectors.

- Temporal recurrence: it must be shown that the innovations or their determinants behave cyclically.

Exposed representatives of the theories regarding the long waves are in particular Schumpeter, Freeman and Mensch.

Schumpeter

An early theory of the long waves came from Schumpeter, especially in his 1939 work Business Cycles.

He assumes that entrepreneurs always have enough investments available, but do not immediately implement them as innovations in the economic system. You start innovating when the economy is in balance. In this situation, dynamic pioneering entrepreneurs take out bank loans to innovate. With the help of the money they woo production factors from other companies and thus manage to enforce the invention in the economic system. During this phase, the demand for credit continues to rise as a large number of entrepreneurs want to follow the pioneers, which leads to an increase in interest rates. At the same time, the costs for the production factors also rise due to the increased demand.

Calculating future profits from innovations is becoming more and more difficult for entrepreneurs. For this reason, fewer innovations are carried out and the upswing comes to a standstill. The lack of new innovations therefore leads to an economic downturn that lasts until the economy is again in a new equilibrium. As soon as this is achieved, according to Schumpeter, there will be entrepreneurs again who innovate and thus contribute to a new upswing.

human

In the theory of Gerhard Mensch (1973) a distinction is made between basic innovations and improvement innovations, whereby basic innovations represent a fundamental change in the established technologies, improvement innovations are only slight changes and improvements to the basic innovations.

In contrast to Schumpeter's theory, Mensch sees the origin of a new Kondratiev cycle not in the phase of economic equilibrium, but in the depression. Here the entrepreneurs no longer want to accept the sadness of this state of affairs and are carrying out basic innovations. As a result, basic innovations emerge in bursts during the depression phase, which ultimately leads to a new upswing phase.

In this the innovations steadily decrease. The lack of innovation ultimately leads to a new depression in which a new upswing can begin.

Freeman

For Christopher Freeman (1982), it is not individual basic innovations that play a prominent role, but so-called technical systems. According to Freeman, a single basic innovation does not have the power to lead to a complete economic upswing. The decisive factor is the diffusion of innovations throughout the economy and the linking of the individual innovations. Only then can the economy experience a strong upturn.

Schoolmaster

The Austrian economist Stephan Schulmeister drafts a political-economic theory of long cycles in which a " real capitalist " boom phase and a " finance capitalist " boom phase alternate. Both phases go hand in hand with a certain intra-capitalist "game arrangement", i. H. a series of fundamental regulatory and economic policy decisions, which in turn are legitimized and recommended by a certain economic theory, which in turn is propagated and enforced by an alliance of the three major social interest groups real capital , finance capital and labor.

The upswing phase is characterized by an (implicit) alliance between real capital ( employers' associations ) and labor ( unions ) against financial capital ( financial industry : banks, insurance companies, investment companies, shadow banks, etc.). There is a real-capitalist game arrangement in which investments in the real economy (which create jobs and good wealth) are more attractive than speculative investments in financial stocks. The financial markets, on the other hand, are strictly regulated. This constellation leads to high growth rates, full employment and is associated with generally optimistic future expectations. The downturn phase, on the other hand, is characterized by an alliance of interests between financial capital and real capital against work and creates a financial capitalist game arrangement in which speculative investments appear more profitable than productive investments in real capital (" casino capitalism "). This constellation leads to falling growth rates in the real economy with booming financial markets and growing speculation euphoria, rising unemployment, rising national debts, financial crises and finally deflation and is characterized by generally pessimistic future expectations.

In the real capitalist boom after the Second World War, under the aegis of an alliance between real capital and labor ("corporatism") against finance capital, the Keynesian theory , which provided the social market economy with the economic policy framework, dominated. The arrangement of the game was designed in such a way that investments in the real economy (and thus the creation of jobs) seemed worthwhile, while the financial markets were strictly regulated and therefore hardly offered any profit opportunities: the international monetary system was designed by the Bretton Woods Agreement in such a way that currency speculation was not was possible. From the point of view of national accounts , it is characterized by a constellation in which (in the case of net saving private households) the corporate sector is indebted and the state budget remains relatively neutral. This game arrangement led to the economic miracle, high growth rates, full employment and an overpowering of work (unions) over real capital (employers' associations) in the 1960s, so that real capital terminated the alliance with work and instead made a pact with finance capital against work.

Now the neoclassical economy (in the form of Milton Friedman's monetarism ) became the dominant economic theory, which made the liberalization and deregulation of the financial and labor markets and the general withdrawal of the state from the economy the main core of its demands ( Thatcherism , Reagonomics ). This resulted in a break in the power of the unions and a "finance capitalist" game arrangement similar to that of the late 1920s. It is characteristic of the financial capitalist game arrangement that investments in financial capital (speculation) appear more worthwhile than investments in the real economy. Therefore, the dominant financial capitalist game arrangement in the downturn is characterized by a constellation in which (in the case of net saving private households) the corporate sector is also a net saver (and its surpluses are not invested in investments in real production, but in financial market speculation), while the state is the opposite must take on the same high level of debt. In this constellation, if the state tries to reduce its deficits (debt brake) without the corporate sector being ready to reduce its surpluses or to go into debt again for real investments, this strategy, which looks at the national budget in isolation, leads to a deflationary crisis ( savings paradox ) .

The real capitalist game arrangement fails because of its success, the finance capitalist game arrangement fails because of its failure: The economic-political constellation of the financial capitalist game arrangement leads to financial crises (like that of 2007 ff.) And a deflationary crisis, which in turn forces the game arrangement to be changed to a real capitalist one .

In the current (2010) situation, which he interprets as the bottom of the long cycle, Schulmeister recommends a New Deal for Europe, which - similar to FD Roosevelt's New Deal from 1933 - enables a peaceful transition to a new real-capitalist game arrangement and extreme political developments ( how to avoid the rise of fascism in the 30s).

Critique of the theory of the Kondratiev cycles

Opponents of the Kondratiev cycles claim that the separation of trend (long-term growth) and cycle (deviating developments) has not yet been resolved. Depending on the choice of the trend component (e.g. using a polynomial ), almost any waves can be generated. According to Norbert Reuter, this problem is already evident from the fact that the popular graphic wave representations never have a label on the y-axis. This is not due to an oversight by the respective author, but to the fact that there are no long series (e.g. of the development of the gross domestic product ) that immediately show such a waveform.

Quantitative science research has made a contribution, statistically examining the “conjunctions” of science and technological research with the help of discovery, publication and patent statistics. Contrary to z. B. the conjectures of Gerhard Menschs, both scientific and technological activities turned out to be extremely cyclical, described as deviations from exponential growth. For Kondratjew cycles or “long waves”, however, what is decisive is the proof that the fluctuations in scientific discoveries over a period from 1500 to 1900 were inversely related to the long waves of economic development. This would confirm the historical existence of long waves, but does not yet imply a causal direction. For example, it is possible that the fluctuations in scientific achievements followed a cyclical financing pattern: economic growth phases allow higher research expenditures with a time lag, which in turn lead to innovations with a delay.

literature

- Nikolai D. Kondratjew : The long waves of the economy . In: Archives for Social Science and Social Policy . tape 56 , 1926, pp. 573-609 .

- Nikolai D. Kondratjew (edited and commented by Erik Händeler): The long waves of the economy: Nikolai Kondratieff's essays from 1926 and 1928 . Marlon Verlag, Moers 2013, ISBN 978-3-943172-36-2 .

- Chris Freeman and Francisco Louçã: As Time Goes By: From the Industrial Revolution to the Information Revolution . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000.

- Carlota Perez : Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages . Edward Elgar, Cheltenham 2002.

- Joseph A. Schumpeter: Business Cycles. A theoretical, historical and statistical analysis of the capitalist process . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1961.

- Leo A. Nefiodow: The fifth Kondratieff . Wiesbaden 1990, ISBN 3-409-13927-3 .

- Leo A. Nefiodow: The sixth Kondratieff . St. Augustin 1996, ISBN 3-9805144-0-4 .

- Erik Händeler : The story of the future . Brendow, Moers 2003, ISBN 3-87067-963-8 .

- Erik Händeler: Kondratieff's world . Brendow, Moers 2005, ISBN 3-86506-065-X .

- Ulrich Hedtke: Stalin or Kondratieff. Endgame or Innovation? (As well as :) Nikolai Kondratieff: Controversial questions of the world economy and the crisis . Dietz, Berlin 1990.

- Peter FN Hörz: Folklore in the sixth Kondratieff. Attempt to determine the position of European ethnology in the knowledge society . In: Bamberg contributions to folklore . tape 1 . Hildburghausen 2004.

- Ernest Mandel : Late Capitalism . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1972, ISBN 3-518-10521-3 .

- Ernest Mandel: The long waves in capitalism. A Marxist explanation . 2nd Edition. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1987.

- Wolfgang Drechsler , Rainer Kattel, Erik S. Reinert (Eds.): Techno-Economic Paradigms: Essays in Honor of Carlota Perez . Anthem, London 2009.

- Stephan Schulmeister : In the middle of the great crisis: a new deal for Europe . Picus, Vienna 2010, ISBN 978-3-85452-586-8 .

- Stephan Schulmeister: Real capitalism and finance capitalism - two "game arrangements" and two phases of the "long cycle". In: Jürgen Kromphardt: Further development of Keynesian theory and empirical analyzes. (= Writings of the Keynes Society. Volume 7). Metropolis, Marburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-7316-1041-0 , pp. 115-170.

- Stephan Schulmeister: The way to prosperity , Ecowin, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-7110-0148-1 .

See also

- Elliott Wave Theory (Grand Supercycle)

Web links

- The new shortages in the information society economy ( Telepolis of July 20, 2004)

- Kondratiev economies (Telepolis of May 24, 2004)

Individual evidence

- ^ Kondratieff Waves in the World System Perspective. In: Leonid E. Grinin, Tessaleno C. Devezas, Andrey V. Korotayev (eds.): Kondratieff Waves: Dimensions and Perspectives at the Dawn of the 21st Century . Uchitel Publishing House, Volgograd 2012, pp. 23-64.

- ^ A b Andrei Korotajew , Sergey V. Tsirel: A Spectral Analysis of World GDP Dynamics: Kondratiev Waves, Kuznets Swings, Juglar and Kitchin Cycles in Global Economic Development, and the 2008-2009 Economic Crisis. In: Structure and Dynamics. Vol. 4, # 1, 2010, pp. 3-57.

- ↑ Ralf Fücks: Growing intelligently. The green revolution. Munich 2013, pp. 164–169.

- ^ Allianz Global Investors: The "green" Kondratieff. April 2013.

- ↑ UBS Investment Research: The New Global Economy. July 2013; McKinsey Global Institute: Disruptive Technologies. Advances that will transform life, business and the global economy, May 2013.

- ↑ Stephan Schulmeister: Real Capitalism and Finance Capitalism - two "game arrangements" and two phases of the "long cycle". In: Jürgen Kromphardt: Further development of Keynesian theory and empirical analyzes. (= Writings of the Keynes Society . Volume 7). Marburg 2013, pp. 115–170 (also online as full text).

- ^ Rudolf Hilferding: The finance capital. A study of the recent development of capitalism. Verlag der Wiener Volksbuchhandlung Ignaz Brand & Co., Vienna 1910.

- ^ Franz Joachim Clauss: Economy and Neoclassic. Saving and investing, public budgets and economic growth in the cyclical economy (USA 1929–1967) . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1968. (Excerpt online ( Memento from May 13, 2014 in the Internet Archive ))

- ^ Stephan Schulmeister: In the midst of the great crisis: a new deal for Europe . Vienna 2010.

- ^ Norbert Reuter: Economics of the "long term". On the evolution of growth bases in industrial societies . Metropolis, Marburg 2000, ISBN 3-89518-313-X , p. 33 ff . (The labeling of the y-axis is, however, basically the case in more recent literature, including Perez or Freeman).

- ↑ R. Wagner-Döbler: Scientometric evidence for the existence of long economic growth cycles in Europe 1500-1900. In: Scientometrics. Vol. 41, 1998, pp. 201-208.

- ^ The anger of the economist (Review by Florian Gasser on zeit.de, May 26, 2018)