Chepesch

| Chepesch in hieroglyphics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Chepesch Ḫpš fore leg / bull leg / foreleg |

||||

Chepesch Ḫpš batting arm, power arm |

||||

Chepesch Ḫpš Chepesch- curved sword |

||||

| Chepesch as a cow's thigh | ||||

Chepesch ( Babylonian gamlu ) is an ancient Egyptian ambiguous term that is derived from Egyptian mythology and was used in ancient Egyptian astronomy , the royal statutes and as a weapon designation. In addition, the "Chepesch" was considered a royal insignia , which in its function as the "Chepesch curved sword of the king" or as a "weapon of victory" ritually symbolized the " beating of the enemy " .

In addition, "Chepesch" was the name of a previously unlocated place in the region between Assiut and Beni Hasan (13th to 15th Upper Egyptian Gau ).

etymology

Due to the similarity of the Chepesch curved sword with Near Eastern weapons, Flinders Petrie initially suspected a name adoption from Ancient Egypt. In the Old Kingdom , however, the original meaning of the term "Chepesch" for the "front leg of the bull" is already attested in the pyramid texts .

Because of the similarity in shape to the “front bull's leg”, the name “Chepesch” used for it served as the namesake for the Chepesch curved sword since the New Kingdom . The consonance with the other Chepesch meaning “force” was certainly of additional importance.

Role in the mouth opening ritual

The oldest etymological and mythological reference has the term “Chepesch” in connection with the mouth opening ritual to the “ Mesechtiu ” used there as a revitalizing tool . The Jumilhac papyrus describes how Horus tears out Seth's foreleg and then banished it to heaven, from which the name “Mesechtiu” was derived.

The “bull's thigh” is also connected with Osiris , since Osiris may have been murdered by Seth in the form of the heavenly bull with his fore thigh as the “weapon of Seth”. This mythological connection leads to the interpretation that the “bull's leg” symbolized both “new life” and “death” for the recipient.

Ancient Egyptian astronomy

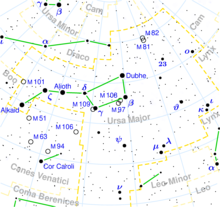

In ancient Egyptian astronomy, the context of the term Chepesch as the “front leg of the bull” was already associated with the constellation goddess Mesechtiu in the Old Kingdom . The other titles of the Mesechtiu are: " He is the one who does not know the end " and " The immortal ". They refer to its mythological-astronomical role , since the astronomical circumstance arose from the Old Kingdom onwards that the constellation of Seth was the only constellation in the sky that did not set.

In the early Old Kingdom, the king saw himself as the embodiment of kingship personified by Horus and Seth. With the beginning of the 4th dynasty , various heavenly deities, in association with Mesechtiu, took on the role of messenger and preparer for the king's ascension to heaven :

“See, the king is rising, see the king is coming. But it does not come by itself. It is your messengers who brought it, the word of God has raised it up. "

In the New Egyptian language , the spelling , which has been partially hieroglyphically altered since the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom, in connection with the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead is striking ; for example, the original name of the deity “Mesechtiu (bull's thigh) in the northern sky” was replaced by the variant “ Chepesch (bull's thigh) in the northern sky ”.

Divine and royal insignia

The Chepesch curved sword is first used around 1550 BC. At the end of the 17th dynasty in the victory report of Kamose , where the sword is handed over to the king, known as the "son of Amun ", after his successful campaigns against the Hyksos . The first documented representation of Chepesch in ancient Egypt was for Thutmose III. proven in knife form. The Chepesch curved sword is attested, among other things, on steles on which Amun presented the weapon to the king. In its capacity as the "divine weapon of Egypt", the Chepesh curved sword was therefore considered an insignia, the royal symbolic use associated with it has been described several times:

“The king was instructed to trample down the lands, to subdue them, to drive them out for Egypt. Month and Seth are with him (the king) in every battle. Anat and Astarte are a shield to him, while Amun determines his testimony. He does not withdraw when he brings the curved sword from Egypt to the Setet Asians. "

The Chepesch as a weapon

precursor

The forerunners of the Chepesch or "Chepesch curved sword" were known to the Egyptians at least since the Middle Kingdom . In the reign of Amenemhet II (end of the 20th century BC) "33 Scimitars" are mentioned on his annal stone , which still bear the hieroglyph

|

The swords from the royal tombs of Byblos are perhaps among the oldest sickle swords. Typologically, the sickle sword is likely to have developed from the Mesopotamian Krummholz and the Near Eastern side blades. A comparable sword comes from Shechem and is also richly decorated. The valuable decoration of these early examples indicates that it was an elite weapon. Similar swords occur occasionally in the Hyksos period graves at Tell el-Dab'a .

Evidence and form

Hans Bonnet noted in 1925 that the classification of the ancient Egyptian Chepesch as "sickle sword" was unsuitable. The blade, ground on one side, takes on a sickle-like shape shortly behind the handle, but typologically the Chepesch cannot be equated with the sickle sword precursors. The classification made in Egyptology as a "curved sword" and also as a "scimitar sword" (" curved saber, saber sword ") was based on the ancient Egyptian innovative further development of the sickle sword.

The ancient Egyptian Chepesch is particularly noticeable due to a greatly changed weapon style: the handle area, including its extension to the blade, had a size of about one third in relation to the Chepesch weapon, while the blade area made up about two thirds. The sharpness of the Chepesch was convex instead of concave compared to a sickle sword . In addition, the Chepesch had a cutting edge similar to the saber . The wedge-shaped blade widened considerably and worked like a long, thin ax . A Chepesch curved sword variant with its saber-like blade could also be used as a stabbing weapon .

Iconographically , the "Chepesch weapon" has been attested since the New Kingdom as equipment used by the king's foot soldiers in Egypt. There are, among other things, numerous images on temple walls. The ancient Egyptian Chepesch curved sword was on average about 50-60 cm long. The handle, about 12 cm long, ended at a protruding section edge that was supposed to protect the hand of the Chepesch wearer from attacks by other people. As a find, the Chepesch is easy to recognize and identify due to its blade shape.

See also

literature

- Jan Assmann : Death and the afterlife in ancient Egypt. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49707-1 .

- John Coleman Darnell, Colleen Manassa: Tutankhamun's Armies: Battle and Conquest during ancient Egypt's late eighteenth dynasty. Wiley & Sons, Hoboken 2007, ISBN 0-471-74358-5 , Chapter: Trampling the nine bows: Military Forces and Weaponry.

- Kenneth Griffin: Images of the Rekhyt from Ancient Egypt. In: Ancient Egypt. Volume 7, Part 2, No. 38. Empire Publications, Manchester 2006, pp. 45-50.

- Kenneth Griffin: A Reinterpretation of the Use and Function of the Rekhyt Rebus in New Kingdom Temples. Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Symposium which took place at the University of Oxford April 2006. In: Current Research in Egyptology. [CRE] 2006, Brill, Leiden / Oxford 2007, pp. 66–84.

- Patrick F. Houlihan, Steven M. Goodman: The birds of ancient Egypt. Aris & Phillips, Warminster 1986, ISBN 0-85668-283-7 , pp. 93-96.

- Irmgard Hein, Christophe Barbotin (eds.): Pharaohs and Strangers - Dynasties in the Dark: Vienna City Hall, Volkshalle, Sept. 8th - Oct. 23rd, 1994. Self-published by the Vienna City Museums, Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-85202-1156- 2 .

- Andrew Hunt Gordon, Calvin W. Schwabe: The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in ancient Egypt. Brill, Leiden 2004, ISBN 90-04-12391-1 .

- Christian Leitz u. a .: LGG . Volume 3: P-nbw. (=: Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta. [OLA] Volume 112). Peeters, Leuven 2002, ISBN 90-429-1148-4 , pp. 398 and 441.

- Christian Leitz: Ancient Egyptian star clocks. Peeters, Leuven 1995, ISBN 90-6831-669-9 .

- Hans Wolfgang Müller, Fritz Gehrke, Hermann Kühn: The weapon find of Balata-Sichem and the sickle swords: With the chemical-physical metal analysis for the weapon find by Hermann Kühn, Deutsches Museum, Munich (= treatises. New series, Issue 97; Bavarian Academy of Sciences [Munich] / Philosophical-Historical Class). Beck, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-7696-0092-4 .

- Eberhard Otto : The Egyptian mouth opening ritual. Part I: Text. ; Part II: Commentary. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1960, ISSN 0568-0476 ; 3.1 and 3.2;

- Sylvia Schoske: curved sword. In: Wolfgang Helck : Lexicon of Egyptology. Vol. 3: Horhekenu-Megeb. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1980, ISBN 3-447-02100-4 , Sp. 819-821.

- Carola Vogel, cut and puncture proof? Thoughts on the typology of the sickle sword in the New Kingdom. In: D. Bröckelmann u. A. Klug (Ed.) In: Pharaos Staat. Festschrift for Rolf Gundlach on his 75th birthday. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2006, 271-286.

- Alexandra von Lieven : Floor plan of the course of the stars - the so-called groove book. The Carsten Niebuhr Institute of Ancient Eastern Studies (among others), Copenhagen 2007, ISBN 978-87-635-0406-5 .

- Alexandra von Lieven: The sky over Esna - A case study on religious astronomy in Egypt using the example of the cosmological ceiling and architrave inscriptions in the temple of Esna. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2000, ISBN 3-447-04324-5 .

- Nicholas Edward Wernick: A Khepesh Sword in the University of Liverpool Museum. In: The Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities. (JSSEA) No. 31, 2004 , pp. 151-154. ( online ; PDF; 64 kB)

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Christian Leitz u. a .: LGG Vol. 3, Leuven 2002, p. 398.

- ↑ a b c Hans Bonnet: The weapons of the peoples of the ancient Orient . Hinrichs, Leipzig 1926, p. 85; Nicholas Edward Wernick: A Kepesh Sword in the University of Liverpool Museum . In: JSSEA 31 . 2004, pp. 151-152; Andrew Hunt Gordon, Calvin W. Schwabe: The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in ancient Egypt . P. 79; John Coleman Darnell, Colleen Manassa: Tutankhamun's Armies . P. 77; Sylvia Schoske: curved sword . Sp. 819.

- ↑ a b c Flinders Petrie: Tools and Weapons: Illustrated by the Egyptian collection in University College, London, and 2000 Outlines from other Sources . School of Archeology in Egypt, London 1917, p. 26.

- ↑ Pyramid Text 653 ; Translation " strong arms " according to RO Faulkner: The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts 1910 . In: Kessinger Publishing's rare reprints . Kessinger Publishing, 2004, ISBN 1-4179-7856-2 , pp. 123 (English, 436 p., Limited preview in Google book search). ; Translation " hips (legs) " according to Samuel Alfred Browne Mercer: The Pyramid Texts in Translation and Commentary . Longmans, Green & Co., New York 1952, p. 129 .

- ↑ Sylvia Schoske: curved sword. Wiesbaden 1980, column 819.

- ^ A b Andrew Hunt Gordon, Calvin W. Schwabe: The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in ancient Egypt. Leiden 2004, p. 78.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Death and Beyond in Ancient Egypt. Munich 2003, p. 167.

- ↑ Christian Leitz u. a .: LGG, Vol. 3 Leuven 2002, p. 441.

- ↑ Atum is symbolic of Ramses II when "knocking down the enemy" according to Flinders Petrie: Hyksos and Israelite Cities . Quaritch, London 1906, plate 30.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: Historical-Biographical Texts of the 2nd Intermediate Period and New Texts of the 18th Dynasty (Small Egyptian Texts) . Wiesbaden 1983, ISBN 3-447-02331-7 , p. 96 (15th line).

- ^ Karen Exell: Soldiers, Sailors and Sandalmakers: A social Reading of Ramesside Period votive Stelae . Golden House Publications, London 2009, ISBN 978-1-906137-10-6 , Fig. 5.8 on p. 124.

- ^ Andrew Hunt Gordon, Calvin W. Schwabe: The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in ancient Egypt . P. 79; with reference to Raymond O. Faulkner: A concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1976, ISBN 0-900416-32-7 , p. 190.

- ↑ Marcus Müller: The effects of war on ancient Egyptian society . In: Burkhard Meißner: War - Society - Institutions: Contributions to a comparative war history . Akademie, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-05-004097-1 , p. 92.

- ↑ Hartwig Altenmüller, Ahmed M. Moussa: The inscription of Amenemhet II from the Ptah temple of Memphis, a preliminary report . In: Studies on Ancient Egyptian Culture (SAK) 18 . 1991, p. 12.

- ^ A b c d e William James Hamblin: Warfare in the ancient Near East to c. 1600 BC . Routledge, London 2007, ISBN 0-415-25588-0 , p. 71.

- ^ Nicholas Edward Wernick: A Kepesh Sword in the University of Liverpool Museum . In: JSSEA 31 . 2004, pp. 151-152.

- ↑ a b c Sylvia Schoske: curved sword . Sp. 820.

- ↑ Pierre Montet: Byblos et l'Égypte: Quatre campagnes de fouilles à Gebeil; 1921–1924 (Bibliothèque archéologique et historique 11) . Geuthner, Paris 1928, plate XCIX.

- ↑ a b I. Hein, C. Barbotin: Pharaohs and Strangers. Vienna 1994, p. 129.

- ^ I. Hein, C. Barbotin: Pharaohs and Strangers. Vienna 1994, p. 133.

- ↑ Śarî'ēl Šālêw: Swords and Daggers in Late Bronze Age Canaan . Steiner, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-515-08198-4 , pp. 55-56.

- ↑ Hans Bonnet: The weapons of the peoples of the ancient Orient . Hinrichs, Leipzig 1926, p. 85.

- ↑ Epigraphic Survey Chicago III: The battle Reliefs of King Sety I (Reliefs and inscriptions at Karnak 4) . The University of Chicago Oriental Institute publications 107, Chicago 1986, ISBN 0-918986-42-7 , Pl.17a.