Munich 21

Munich 21 was a project within the scope of Bahnhof 21 planning by Deutsche Bahn AG with the aim of adding a through station underground to the terminal station of Munich Central Station . This measure should, among other things, save time for regional and long-distance traffic.

The project emerged from considerations of the Free State of Bavaria , Deutsche Bahn and the state capital Munich , which began in the mid-1990s, and were looking for solutions to improve rail traffic in the Munich area.

The realization of the project is currently (status: 2010) on hold.

features

Deutsche Bahn AG, the Free State of Bavaria and the City of Munich commissioned a feasibility study to examine whether and, if so, how the terminus could be converted into a through station .

As part of the study, which was completed in autumn 2001, two alternatives (A, B) with a through station at the main station and a tunnel to the east station were examined. In addition, the city of Munich introduced an alternative variant Laim-Südring (ALS) , which provided for a link between the long-distance traffic and regional traffic at Munich-Laim station .

The tunnel should be parallel to the existing tube of the main S-Bahn line . The Suedring should no longer traveled in the variants A and B long-distance and regional traffic.

Alternative A

The Alternative A provided for a 14-track main railway station as a through station for the entire passenger traffic. The facility, located in an open trough at a depth of around 18 m, was to be followed by a four-track tunnel to Munich's Ostbahnhof , which was to be used by all trains. At Sendlinger Tor , a new City stop was to be created with six platform tracks for regional traffic, with transfer options to the U3 and U6. The four-track tunnel would have come to the surface in the Welfenstrasse area and would have been threaded into the Ostbahnhof parallel to the tracks on the Südring. With this solution, up to ten platform tracks (plus S-Bahn ) would have been required at the Ostbahnhof .

The travel time for long-distance traffic between the main and east stations would have been reduced from eight minutes (via the Südring) to five minutes. In regional traffic - due to the stop at the City stop - an unchanged travel time was expected. In the tunnel 102 were ICE -Zugpaare expected at the breakpoint 158 pairs of trains of inter-regional and the City Express per day '. 691,000 additional long-distance passenger journeys (over 50 km travel distance) were expected in long-distance traffic. Around 7,100 additional journeys per day were expected within the Munich transport association . Around 21.4 hectares of land should be released for new uses.

The conversion of the tracks of the main train station during ongoing operations would have required many construction phases and long-term impairment of the access offer. The underpassing of the Mathäserkomplex would have made expensive special tunnel construction necessary. The ICE depot would have been relocated to the former marshalling yard in Munich East .

The necessary investments were put at around 2.095 billion euros.

Alternative B

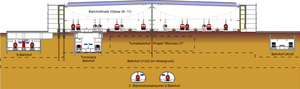

The Alternative B provided for a focused on 16 tracks railway terminus for the Western relations. In addition, a through station with six platform tracks at a depth of about 18 m was planned, which should serve the long-distance traffic Germany – Austria / Italy as well as the regional traffic Ingolstadt - Mühldorf and Augsburg - Rosenheim . A double-track tunnel with a four-track City-Bahnhof Sendlinger Tor was to be built for regional traffic to the Ostbahnhof . Above ground, 16 tracks with a length of 420 m each would have been planned in the main hall, while the underground through traffic would have been routed on six platform tracks in the middle below the hall, at a depth of approx. 18 m. The platform hall itself would have been extended, the main entrance would have been preserved and the entrances to the two wing stations would have been optimized. An additional main driveway on Arnulfstrasse should allow access to the platforms via the Paul Heyse underpass. The transfer time between the north and south tracks should be reduced by eleven minutes.

Compared to alternative A, investment costs of around 1.225 billion euros were expected. An increase in long-distance traffic by 422,000 passenger journeys per year was expected. Around 3,800 additional journeys per day were expected within the Munich transport network. By dispensing with the two wing stations, around 4.4 hectares should be free. The inner city tunnel would have been used by 32 ICE, 24 IR and 56 regional train pairs per day.

recommendation

The experts, steering committee and administration of the City of Munich recommended that alternative B be kept open in the long term.

Passenger forecasts for the period up to 2010 did not suggest a sufficient economic cost-benefit ratio . However, as part of the planned modernization of the main train station, Munich 21 will be kept open as a long-term option. The second S-Bahn main line is to run below the tracks of Munich 21, at a depth of around 40 meters . In addition to the route submitted in 1996, an alternative route developed later at a depth of around 40 meters will also be kept free (status: 2006).

As part of the concept, a bicycle parking garage was to be built north of the Starnberg wing station. The three-story building was to accommodate 850 bicycles on three levels. (Status: 1999)

history

prehistory

As early as the late 1930s, there were specific plans to replace the terminus with a through station in a different location. These plans were not implemented due to World War II .

Early concrete plans for long-distance traffic to pass under the city center provided for a long-distance train station below the Old Botanical Garden , which was to be connected underground with the main train station and Karlsplatz . The DB planners did not consider it possible to go under the main station due to the large number of S-Bahn and U-Bahn tunnels crossing at different levels. The DB rejected these plans with reference to the high-quality location of the existing main train station and the wish that the new long-distance train station would have to be reached by daylight.

An investigation of a main train station in the underground showed that these systems must be at a depth of at least 35 m below the surface. A design by the architect Meinhard von Gerkan envisaged a 250 m long, cascading stepped funnel with a width of 100 m. The railway system should be at a depth of 37 m. 45 m above the platform level there should be a 110 m wide and about half-glazed roof. The 50 m high hall was to be bordered on both sides by six gallery levels. A total of 400,000 square meters of floor space was to be created. The existing building should not be included.

idea

On June 20, 1996, the project was presented by railway boss Heinz Dürr , Bavaria's Minister of Economic Affairs Otto Wiesheu and Munich's Lord Mayor Christian Ude . The concept envisaged merging the routes coming from the west in Munich-Pasing and Munich-Laim and reducing them to six from the level of the Friedenheimer Bridge and leading them underground in a 2.3 km long tunnel to the main train station. The main station should be torn down and completely rebuilt. The Frankfurt 21 project had been presented in Frankfurt am Main three days earlier .

A first draft by Meinhard von Gerkan envisaged a 265 m long and 110 m wide platform hall with eight tracks and four central platforms at a depth of 35 meters. Between the entrance level (ground floor) and the approximately 35 m lower platform level, four gallery levels with different functions were provided. The hall, which is up to 35 m below street level, should have a ceiling height of 50 m.

Two single-track tubes, 3.3 km long and passable at 120 km / h, were to be built from the main station to the Ostbahnhof.

A green area about three kilometers long and 160 m wide was to be created on the current track system. In addition, around 120 hectares of building land for mixed use (60 percent work, 40 percent residential) should be created. Cross traffic should be guided over bridges and shielded by peripheral structures on both sides.

The project was supposed to do without federal funding. A period of 15 to 20 years was initially mentioned as the implementation period. The cost was given as about 5 billion DM.

Further development

On January 29, 1997, the city council of the state capital commissioned the city planning department to award a preliminary study in which city-friendly alternatives to Munich 21 should be developed. The results showed leaner solutions with a less deep through station and shorter tunnels. The city council took note of the results of the preliminary study on July 15, 1998 and instructed the planning department to examine the main alternatives in a feasibility study.

In the late summer of 1999, the project was one of those that probably should not be implemented due to the federal government's austerity constraints. An examination of the city planning office showed that in the best case only a quarter of the financing could be covered. The city announced that it wanted to develop 160 hectares of railway areas between the main train station and Pasing, which would be vacated anyway.

In the spring of 2000, the Munich city council was skeptical as to whether the Munich 21 project could be implemented.

In mid-2001 it became known that Deutsche Bahn had deleted the project from its medium-term expansion concept (until 2015). The project was therefore not included in a list of projects that the company proposed for inclusion in the Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan. Previously, the company had already removed Munich 21 from its medium-term financial planning (until 2005). According to a railway spokesman in 2001, the Stuttgart 21 project was more important to the company than Munich 21, as more trains would start and end in Munich than in Stuttgart. A through station in Munich would be less useful.

Feasibility study

In 1998 a feasibility study was commissioned by the Free State, City and Railways and the following year the question of the second trunk line tunnel versus the Südring variant was added. The study envisaged lowering the main station from the height of the Donnersbergerbrücke to a height of 19 m. Two variants were investigated. One involved a complete lowering of the main train station, including a four-track tunnel to the Ostbahnhof, a new connecting station with the subway at Sendlinger Tor and an S-Bahn that already ran underground at Donnersbergerbrücke. A second variant was to keep the terminus for trains ending in Munich and to connect the new underground railway systems to the Ostbahnhof with a double-track tunnel. The construction of a long-distance train station under Marienplatz was also considered.

A total of five studies were commissioned as part of the feasibility study, based on five objectives:

- "Increasing the traffic benefits for customers and transport companies"

- "Fulfillment of railway operating requirements and guarantee of technical feasibility while maintaining rail operations during the construction period"

- "Clearance of terrain for urban development options"

- "Impulses for a structural further development of the city in the sense of an improved transport offer in rail-bound regional and long-distance traffic with positive effects for the environment"

- "Effort and cost minimization in the operating processes of the railway and granting of advantages for the railway customers through shorter distances and transfer times"

The work was temporarily interrupted and, at the request of the Free State of Bavaria, a supplementary S-Bahn investigation was carried out in two variants, the results of which were presented to the city council on October 24, 2001. A contemplated joint use of the new railway systems by the S-Bahn was largely rejected. Work on the feasibility study was completed in autumn 2001.

The results of a subsequent study were issued in March and April 2002.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b "Railway Concepts" in the Plan-Treff . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , No. 57, 2002, ISSN 0174-4917 , p. 45n.

- ↑ Michael Schoberth: Munich 21 was buried early. In: Stuttgarter Zeitung . June 14, 2010, accessed October 2, 2016 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q City of Munich, Department for Urban Planning and Building Regulations (ed.): Decision of the Committee for Urban Planning and Building Regulations of June 19, 2002 . June 19, 2002, p. 3–13, 17, 18 ( online [PDF]).

- ↑ Uwe Weiger: New face for an old successful model - the Munich S-Bahn in transition . In: Eisenbahn-Revue International , Issue 1/2001, ISSN 1421-2811 , pp. 37–43.

- ↑ a b Bavarian State Ministry for Economic Affairs, Infrastructure, Transport and Technology / State Capital Munich, Department for Urban Planning and Building Regulations (Ed.): Central Station Munich. Results of the workshop procedure for revising the selected competition concepts. Munich, September 2006, p. 12 f.

- ^ Eberhard Thiel: Station Munich 21 . The feasibility study. In: outlines . tape 1 , 2001, ISSN 1437-2533 , ZDB -ID 2042882-0 , p. 148-149 .

- ↑ Dominik Hutter: The main train station is becoming a monster construction site . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , January 9, 2006, p. 53.

- ↑ Wrecking ball comes in May . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , No. 79, 1999, ISSN 0174-4917 , p. W1.

- ↑ Edmund Mühlhans, Georg Speck: Problems of the terminal stations and possible solutions from today's perspective . In: International Transport . tape 39 , no. 3 , 1987, ISSN 0020-9511 , pp. 190-200 .

- ↑ a b Meinhard von Gerkan : Renaissance of the train stations as the nucleus of urban planning . In: Renaissance of the railway stations. The city in the 21st century . Vieweg Verlag , 1996, ISBN 3-528-08139-2 , pp. 16-63, in particular pp. 61 f.

- ↑ a b Association of German Architects u. a. (Ed.): Renaissance of the railway stations. The city in the 21st century . Vieweg Verlag , 1996, ISBN 3-528-08139-2 , pp. 170-177.

- ↑ a b c d The main train station should be swallowed by the earth . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , No. 141, 1996, ISSN 0174-4917 , p. 39.

- ↑ a b c d Profile: Munich 21 . In: tunnel . No. 6 , 1996, ISSN 0722-6241 , p. 44-45 .

- ↑ Elmar Waller response: remote train tracks beneath the earth: Stuttgart idea is imitation in Frankfurt and Munich . In: VDI news . July 5, 1996, ISSN 0042-1758 , p. 4 .

- ^ Meinhard von Gerkan : Architecture for Transportation. Architecture for traffic . Birkhäuser-Verlag, Basel, 1997, ISBN 3-7643-5611-1 , pp. 194-203.

- ↑ a b Frankfurt 21 and Munich 21 are examined for feasibility . In: The Railway Engineer . tape 47 , no. 8 , 1996, pp. 39 .

- ↑ Announcement Billion Holes . In: Eisenbahn-Revue International , issue 10, year 1999, ISSN 1421-2811 , p. 401

- ↑ Dankwart Guratzsch: Railway station projects are threatened . In: The world . No. 171 , July 26, 1999, ISSN 0173-8437 , p. 14 ( online ).

- ↑ a b Lower it or bury it completely . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , No. 113, 2000, ISSN 0174-4917 , p. L1.

- ↑ No money for the new Munich 21 train station . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , No. 158, 2001, ISSN 0174-4917 , p. 41.

- ↑ a b The castle in the air principle . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , No. 39, 2001, ISSN 0174-4917 , p. 49.

- ↑ Bahn lets ICEs stop at Marienplatz . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , No. 161, 1998, ISSN 0174-4917 , p. L1.