Johann Mattheson

Johann Mattheson (born September 28, 1681 in Hamburg ; † April 17, 1764 ibid) was a German opera singer (tenor), composer , music writer and patron .

Life

As the son of a wealthy Hamburg merchant, Johann Mattheson received extensive training in foreign languages (English, French, Italian and Latin) as well as in the musical field (singing, violin , organ and harpsichord ). One of his teachers was the organist Johann Nicolaus Hanff . Gradually he also learned the gamba , recorder , oboe and lute .

At the age of nine he was already singing, accompanying himself on the harp . He was an organist and member of the Hamburg Opera Choir . A few years later he sang there as a soloist, conducted rehearsals and composed his first opera in 1699 ; he directed the performance himself and sang a leading role.

In 1703 he met Georg Friedrich Händel here and formed a lifelong, if not unproblematic, friendship. They intensively exchanged their knowledge, even when there were tangible arguments about musical views. During a performance of Mattheson's opera Cleopatra , a dispute over musical direction arose which ended in a duel . A button on Handel's jacket prevented serious injury. The opponents reconciled that same evening. However, Mattheson apparently felt himself disliked by Handel throughout his life.

Mattheson and Handel applied to succeed Dietrich Buxtehude as organist in Lübeck , but neither of them accepted. Eventually the office was taken over by Johann Christian Schieferdecker , who was willing to marry Buxtehude's eldest daughter, which was set as a condition. Mattheson and Handel returned to Hamburg, where in 1704 Mattheson received the post of court master, soon also secretary and correspondent of the English ambassador , which he exercised well into old age and who ensured him a livelihood and a high social status. In the following year he finished his work as an opera singer and married Catharina Jennings, an English pastor's daughter, in 1709; the marriage remained childless.

Between May 31, 1713 and May 26, 1714, Mattheson published the journal Der Vernfungler in Hamburg , the first German-language “ Moral Weekly ”. These were excerpts from the two English magazines Tatler and Spectator , aimed at Hamburg's circumstances and translated into German . Although the magazine was only published for a year, it had a lasting influence on "the entire development of the German literary language."

In 1715 he became vicar and in 1718 music director at Hamburg Cathedral . He had to give up this position in 1728 when there was a serious argument with the singers of his oratorios, who from then on boycotted him. In addition, his hearing deteriorated significantly, his hearing loss became more and more severe until he became completely deaf.

In this late period he wrote works on music theory, such as the general bass school (1731), the exemplary organist rehearsal (1731), core melodic science, consisting of the most exquisite main and basic teachings of the musical art of composition or composition (1737) and the perfect one Capellmeister (1739), who was presented and reviewed in detail by Lorenz Christoph Mizler in his musical library . He also published magazines, such as the first German music magazine Der musicalische Patriot (1728/29), and translated novels and specialist literature from English, French, Italian and Latin.

His basis of an Ehren-Pforte from 1740 is a comprehensive work of 149 musicians, some of whose biographies he knew through personal contact, many of the articles are also autobiographies that would not have been written without Mattheson's request. In 1761, just two years after Handel's death, he published the German translation of John Mainwaring's first Handel biography , Memoirs of the Life of the Late George Frederic Handel , the first ever biography of a composer to be published in book form .

At Mattheson's funeral, the oratorio The Merry Death Song , composed by himself for the occasion, was played . He was buried in the vault of the St. Michaelis Church in Hamburg, where his tomb is still visible to the public today. With this tomb “in eternity” the recently rebuilt church returned the favor for his legacy of 44,000 marks for the construction of a new organ that he had designed together with the organ builder Johann Gottfried Hildebrandt .

Mattheson's view of music in a music-sociological context

In contrast to the zeitgeist at the beginning of the 18th century, Mattheson took the view that music should not be theological, but social. According to Mattheson, music should follow its own rules and not be subject to externally imposed contrapuntal rules that force it into an apparently well-designed corset. It should not be composed and played solely for God's glory ( Soli Deo Gloria ), but rather to please people and to please them and others. a. to move to dance. Mattheson therefore shaped a socially oriented understanding of music that was atypical for his time - following the example of the gallant style emerging in France , which always assumed an elitist, exclusive image of man.

In addition, Mattheson was bothered by the fact that, first of all, many musicians were uneducated and often poorly paid and therefore, in his opinion, the quality of the music was not “gallant” enough. Second, many sacred music texts in Germany were written in Latin and were therefore not understood by the general public, which meant they could not be "gallant" either. Third, the audience usually recorded music without criticism or reflection in the sense of a mere consumer good. Not only the musicians are to blame for bad music, but also the audience, who actively contribute to its deterioration by accepting all quality levels of music. But, in his opinion, the musicians of that time could also contribute to better music practice by engaging with the music itself and not being influenced by music critics.

Works

Mattheson composed six operas (and made further arrangements of foreign operas), 33 oratorios, orchestral works and chamber music . Most of his works are kept in the Hamburg State Library. They have been missing since they were relocated during World War II and were returned from Yerevan in Armenia in 1998 .

Operas

- The Plejades, or the Seven Stars ( Friedrich Christian Bressand ), Singspiel, Hamburg 1699 and Braunschweig 1699; Music largely lost

- The noble Porsenna (Bressand), Singspiel 4 acts, Hamburg 1702.

- The death of the great Pan , funeral music (gate of honor: "Trauerspiel") on the opera founder Gerhard Schott (Hinsch), 1702 Hamburg; Music (partly by Georg Bronner ) lost

- Victor, Hertzog der Normannen , (Hinsch), pasticcio 3 acts, 1702 Hamburg (1st act by Schieferdecker , 3rd act Bronner); Lost music

- The unfortunate Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt or The betrayed state love ( Friedrich Christian Feustking ), dramma per musica 3 acts, October 20, 1704 Hamburg (score: Schott, Mainz)

- Le Retour du siècle d'or, that is the return of the golden age (Countess Löwenhaupt, perhaps Amalie Wilhelmine von Königsmarck ?), French Operetgen, Holstein 1705, Nehmten and Perdoel; Lost text and music

- Boris Goudenow , or The Throne Acquired by Deviousness (Mattheson), dramma per musica 3 acts, Hamburg 1710, not performed until 2005 (in Hamburg concert / in Boston staged)

- The secret events of Henrico IV, King of Castile and Leon, or Die divided love (Johann Joachim Hoë) February 9, 1711 Hamburg

Oratorios

- The healing birth and incarnation of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ Hamburg 1715.

- Chera or the suffering and consoled widow zu Nain Hamburg 1716.

- Cum Christo. The Savior desired and obtained. Oratorio at Christmas Hamburg 1716.

- Jesus tortured and dying for the sin of the world ( Barthold Heinrich Brockes ) Hamburg 1718

- The most gratifying triumph or the overcoming Immanuel Hamburg 1718.

- The happily arguing church of Hamburg 1718.

- The fruit of the spirit (Neumeister) Hamburg 1719.

- Christi Wunder-Wercke with the weak believers (Hoefft) Hamburg 1719.

- The divine provision over all creatures (King) Hamburg 1718 or 1721.

- The resurrection of all dead (King) Hamburg 1720 confirmed by Christ's resurrection .

- The biggest child in an oratorio at Weynacht Hamburg 1720

- The bloodthirsty Kelter-Treter and the human son Hamburg 1721 raised by the earth .

- The erring and redrawn sins Schaaf Hamburg 1721.

- The Prince of Victory Hamburg 1722, sought among the dead and found among the living .

- The great in the small or God in the heart of a believing Christian Hamburg 1722.

- The Song of the Lamb ( Christian Heinrich Postel ) Hamburg 1723

- The loving and patient David Hamburg 1724

- The heavenly Daniel (Schubart) Hamburg 1724 freed from the lions' ditch .

- The godly secret (Neumeister) Hamburg 1725.

- The unsanctionable Jerobeam (Mattheson) Hamburg 1726.

- Joseph (Schubart) Hamburg 1727, who was merciful towards his brothers .

- The Word of Promise (Wend) Hamburg 1727, fulfilled through the Incarnation of the Eternal Word .

- The happy death song (Mattheson) Hamburg 1760/61, April 25, 1764.

Chamber music

- XII Sonates à 2-3 flutes sans basse , Amsterdam 1708, Mortier, 2teA 1708, Roger

- 12 suites for harpsichord / as Pièces de Clavecin en Deux Volumes Hamburg 1714 / Harmonisches Denckmahl , London 1714.

- The useful virtuoso . Twelve sonatas for violin or transverse flute & basso continuo. 1717, printed in Hamburg 1720.

Fonts (selection)

- The newly opened orchestra . Hamburg 1713, koelnklavier.de and digitized at Books.Google.de

- The protected orchestra . Hamburg 1717, Imslp.org and digitized at Books.Google.de

- Exemplary organist rehearsal . Hamburg 1719 Digitized at Books.Google.de

- The useful virtuoso . Hamburg 1720.

- The inquiring orchestra . Hamburg 1721, Imslp.org

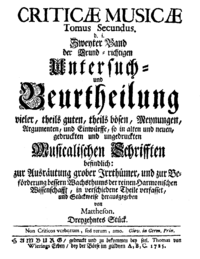

- Critica musica . Hamburg 1722–1725 (Google Books: Volume 1 , Volume 2 )

- The musical patriot . Hamburg 1728. [1]

- Grosse General-Baß-Schule Or: The exemplary organist rehearsal . Hamburg 1731, archive.org

- Small thoroughbass school . Hamburg 1734.

- Core of melodic science . Hamburg 1737.

- The perfect capellmeister . (PDF) Hamburg 1739; Excerpts and complete digitization

- Basis of an honor gate . Hamburg 1740, archive.org

- The latest study of the Singspiele . Hamburg 1744.

- Claim of Heavenly Music . Hamburg 1747.

- Georg Friderich Handel's biography . Hamburg 1761 (German translation of Mainwaring's Memoirs, with additional material)

- John Mainwaring: Life and Music of Georg Friedrich Handel . Foreword and translation by Johann Mattheson. Revised new edition. Heupferd Musik Verlag , Dreieich 2010, ISBN 978-3-923445-08-0 .

estate

- Texts from the estate . Edited by Wolfgang Hirschmann and Bernhard Jahn. Writings on the categories: Biographical, Journalism, Philosophy and Aesthetics, Theology and Morals, Music, Poems. Hildesheim 2014, ISBN 978-3-487-14531-0 . review

literature

- Holger Böning : The musician and composer Johann Mattheson as a Hamburg publicist. Study of the beginnings of moral weekly papers and German music journalism (= press and history. Volume 78). 2nd, completely revised and greatly expanded edition on the 250th anniversary of Johann Mattheson's death. Ed. Lumière, Bremen 2014, ISBN 978-3-943245-17-2 .

- Holger Böning: Born to music. Johann Mattheson; Singer at the Hamburg Opera, composer, cantor and music journalist; a biography. Ed. Lumière, Bremen 2014, ISBN 978-3-943245-22-6 .

- Semjon Aron Dreiling: Pompous funeral procession to the simple grave. The forgotten dead in the vault of the St. Michaelis Church in Hamburg 1762–1813 . Medien-Verlag Schubert, Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-937843-09-4 . (on his grave and the funeral ceremonies in the main church St. Michaelis, Hamburg)

- Robert Eitner : Mattheson, Johann . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 20, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1884, pp. 621-626.

- Simon Kannenberg (ed.): Studies on the 250th anniversary of Johann Mattheson's death. Music writing and journalism in Hamburg , 2nd revised edition. Weidler, Berlin 2017 ISBN 978-3-89693-639-4 (music and new series, 12).

- Hans Joachim Marx : Mattheson, Johann. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 16, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-428-00197-4 , p. 402 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Peter Päffgen: ... a fighting spirit obsessed with progress ... Johann Mattheson ./. Lute. In: Guitar & Laute 9, 1987, No. 6, pp. 35-39.

Web links

- Works by and about Johann Mattheson in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Johann Mattheson in the German Digital Library

- Johann Mattheson at Operissimo on the basis of the Great Singer Lexicon

- Sheet music and audio files

- Sheet music and audio files by Johann Mattheson in the International Music Score Library Project

- Probstücke digital , digital edition of the 24 test pieces of the upper class

- Sonatas for 2 solo instruments

Individual evidence

- ↑ Mattheson. In: Music in the past and present.

- ^ A b Hans-Jürgen Gut: Newspapers in Hamburg and their editors / publishers, in: Zeitschrift für Niederdeutsche Familienkunde, 93rd volume, issue 2, 2nd quarter 2018, p. 249

- ↑ Martin Krieger: Patriotism in Hamburg . Böhlau Verlag, Cologne et al. 2008, p. 126.

- ↑ Michael Bergeest: Education between Commerz and Emancipation, adult education in the Hamburg region of the 18th and 19th centuries , Wachsmann-Verlag, Münster and New York 1995, p. 63, ISBN 3-89325-313-0 ( digitized version )

- ↑ Wolfgang Martens: Der Patriot , Volume IV, Commentary Volume, Walter de Gruyter-Verlag, Berlin and New York 1984, p. 346, ISBN 3-11-009931-4 ( digitized version )

- ↑ Blakall 1966, p. 48, quoted in: Peter von Polenz: German language history from the late Middle Ages to the present . Volume II, 17th and 18th centuries, Walter de Gruyter-Verlag, Berlin and New York 1994, p. 315, ISBN 3-11-014608-8 ( digitized version )

- ↑ Jürgen Neubacher: The singers in Mattheson's church music and his failure as cathedral cantor. Cause and effect of a self-inflicted boycott. In: Jahn, Hirschmann: Mattheson as initiator and mediator . 2010.

- ↑ Birger Petersen-Mikkelsen: The melody theory of the perfect Capellmeister by Johann Mattheson .

- ↑ Quoted from Donald Burrows: Handel . Oxford University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-19-816649-4 , p. 465.

- ↑ Peter Sühring on February 22, 2015 on info-netz-musik ; accessed on March 17, 2015

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Mattheson, Johann |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German opera singer (tenor), composer, music writer and patron |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 28, 1681 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hamburg |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 17, 1764 |

| Place of death | Hamburg |