Fool attributes

Fool attributes are items of equipment and appearances that are commonly associated with the figure of the fool . The idea of what a fool can normally be recognized by developed in the European Middle Ages between the 12th and 15th centuries; until about 1500 the fool had a wide variety of attributes.

Frequency of publication

Nudity

Biblically speaking, nudity is an outward sign of man's turning away from God: Adam and Eve only recognized their nudity after eating the forbidden fruit ( Gen. 3: 7). With the advent of a catalog of deadly sins , carnality and horniness appear as vices that particularly cling to fools. While a pious person follows caritas ( love of neighbor ), the fool subscribes to carnal love (Latin amor carnalis ). In order to show his closeness to the vice of carnality, a fool is usually portrayed naked in iconography . In the 14th and 15th centuries, the fool often shows himself together with a naked lady, while he himself bares his genitals. In relation to the Bible, nudity is a metaphor for dishonor and depravity.

Haircut

While the early fool from the 12th and 13th centuries shaved his head completely according to his nakedness, illustrations appear later that show the fool with the typical monk's tonsure, but often he was given two or three wreaths of hair. The tonsure was seen in the West as a sign of humility and thus as a restriction of the shorn's claim to power and perfection. While various tonsures are attested in ecclesiastical areas, the two- or three-ring hairstyle does not appear anywhere - except for fools. In research it is assumed that this hairstyle deliberately confronts the clergy in order to make them look ridiculous in order to appear again in the typical fool's position: Non est deus . In connection with nudity, it does not seem surprising that in the Old Testament the complete shaving of the head hair was regarded as a severe punishment of honor. This fact continues to have an effect in the Middle Ages, for example the Franconian houseman Pippin had the last Merovingian king Childerich sheared in the 8th century after his formal assumption of the royal dignity .

Fool's Mark and Fool's Stone

In some depictions of fools, but also in carnival masks , there is a festering ulcer on the forehead of the fool , the fool's mark. The closest explanation is that the people of the 15th century - since then the fool's forehead mark has been known in representations - assumed that folly was a disease that grew in the head and that in severe cases it came to light with malignant skin changes. In this context, the many paintings and depictions of the 15th and 16th centuries about stone or fool cutting can be seen. Here the folly is to be operated on from the head of the sick person, mostly with bogus methods. In some places, however, fools carried a stone with them as an attribute and claimed that it had been removed from them.

Apart from this explanatory model, a biblical explanation is also possible with the forehead mark : Within the visual arts around 1500, the apocalypse of John was on everyone's lips due to eschatological thinking . This passage in Revelation 13 : 16-17 and 16: 2 says that all those who have become addicted to the Antichrist would have a mark on their foreheads. Opposite these are the elect who are spared from the judgment and therefore have the signum dei on their foreheads , the sign of God (Rev. 7,3).

Here, too, the antithetics is shown between the pious man as a man of God and the fool as a follower of the devil; the mark of God is opposed to the mark of God as a negative stigmatizing sign. With the forehead of foolishness, the connection to the carnival and fasting custom can be seen to this day . Sebastian Brant mentioned in his second edition of the ship of fools the carnival jester who does not want to receive the ash cross on Ash Wednesday . It is precisely this sign, the sign of God, that believing Christians receive, while the fool is denoted by the devil's forehead mark.

clothing

garment

Until the 16th century, the typical fool's clothing with a cowl on which bells hang, the short-cut dress, the Mi-Parti , spiked shoes and tassels could not be regarded as a uniformly established court jester costume. Often fools, as members of the court, wore a servant's dress, which was marked by the heraldic colors of the master. It is not uncommon for him to appear in a divided dress that, like the liege's coat of arms , showed divided colors. This colored division was in part a sign of dependency and belonging into the 18th century. However, the dress did not necessarily have to be cut in the Mi-Parti. It is therefore not an exclusive sign of the fool to wear a color-split dress. It was also customary to have the dress jagged or fringed, which should indicate the discontinuity of the fool.

The minstrel's dress was constitutive for the fool's dress. The minstrel costume, conspicuously colorful and patterned and thus reflecting the secular nature of the music, also represented, like that of the fool, the connection to the dishonorable and indecent, inconsistent and vagabond way of life. Since the minstrels were excluded from the sacraments and church fellowship, they stood at The fringes of society and thus on a similarly lower social level as the fools. Furthermore, minstrels often took on the function of artificial fools, that is, court jesters; this underlines the closeness to the typical fool.

The bright colors and the bells also make the vicinity of the mentally ill to lepers, the lepers , much that had to do with their chattering and her dress to attract attention. Often the colors yellow and green were used, which were considered the colors of madness . Yellow in particular had a bad meaning in the Middle Ages, as the harmful influence of saffron was attributed to it.

Thus, the standard clothing of the fool, as it has been documented since the beginning of the 15th century, has two roots: It shows characteristics of the goal dress of natural fools, paired with the clothing elements of the artificial fools, the minstrels. In order to additionally mark the low status of the fool, the servant clothing also plays a role. The resulting dress of the fool makes clear his low origin, his closeness to dishonest professions and thus to vice.

The fool often wore a wooden sword on the belt of his robe.

Cowl / fool's cap

The fool's cap is one of the most recent fool attributes. It developed in the 14th century from the Gugel, which was widespread at the time . The cowl was worn by the common people and is similar to the hoods of the monks . The fool's cowl differed from the conventional cowl initially through more colorful colors, a particularly long hood tip or several tips. Through them the fool showed himself to be a godless wicked. Up until the 15th century, the fool's headgear was supplemented by other attributes: dog-ears, bells and / or a cockscomb.

Today, the fool's cap is often worn in a modernized form during carnival or Mardi Gras and is one of the most important symbols of the Rhenish Carnival.

Dog ears

With reference to the eccentric cowl, another characteristic of the fool emerged in the second half of the 13th century with the dog-ears: of the many tips on the cowl, two protruded vertically upwards, which over time turned outward as ears pointed auricles. The relationship with the donkey can u. a. follow a Middle High German song, where a donkey disguises itself as a lion, but betrays itself through its protruding ears ( ... da erhos an im sin meister esels oren, he punished him with slegen, daz he vil krftelos gelak: so close the gates ... - then his master saw donkey ears in him, so he punished him until he lay limp: this is what happens to fools). The donkey was a fundamentally negative animal in allegory : it stood for the vice of indolence ( acedia ), was stupid (cf. today's swear word stupid donkey ) and thus ignorant, thus an example of the heresy of those who deny God. Therefore, according to the medieval view, the donkey received the long ears of the devil at creation. In view of the fool's distance from God or devil's closeness, the fool's dog-ears are not surprising. Countless evidence proves that donkey ears were clearly accepted as a relevant fool attribute in the 15th century: For example, Sebastian Brant in the ship of fools depicts a fool with a knocked back cowl, who actually grew real donkey ears. In today's Carnival, some fully developed donkeys or fools with a donkey mask appear, e.g. B. the donkey in Villingen .

Rooster head

The unequivocal negative name of the fool is a cock's head, which was later reduced to a cockscomb . It is located directly between the dog's ears on the top of the cowl. In the medieval interpretation of animals, the rooster is more often represented as a positive figure, but here it has a negative connotation: the embodiment of the vice of sexual desire. The fool as homo carnalis (man of the flesh) cannot control his sexual appetites and is identified as such by the cock's head or crest. The fact that the cockscomb is even replaced by an erect penis in rare late medieval depictions is entirely in keeping with the tradition of the cock and its lust. You can still find a remnant of this symbol with the fool's cap in the Rhenish Carnival .

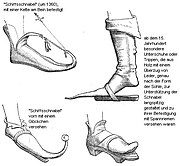

Beak shoes

Like the tonsure with multiple wreaths, the bells, the cowl, the quirk and other attributes, the spiked shoes represent a spoof of the clergy. While monks often appear barefoot - in the sense of asceticism and humility - the fool adorns himself with expensive, fur-trimmed or velvety shoes that were curved upwards as an ornament, which also consumed material. He is therefore guilty of superbia , pride or vanity , one of the seven deadly sins . The deadly sins are closely related to the fool and the devil; anyone who is guilty of a mortal sin will be tormented with hellish punishments after death.

Ring

Bells gained so much importance as a fool's attribute in the 15th century that they were even considered the most important characteristic at times. As early as the early 14th century, there is isolated evidence of a fool from Psalm 52, whose fool's cap has round decorations; but it is not certain whether these are actually clamps. Illustrations in the D initial of the Psalm, in which the fool wears bells clearly equipped with a sound slot, appear safer. While in the High Middle Ages the wearing of so-called tintinnabula (English bells) was reserved exclusively for the emperor as a positive symbol, in the late Middle Ages a clothing fashion developed to adorn oneself with bells and bells ( bell costume ). While this fashion was considered old-fashioned and completely vulgar towards the end of the 15th century and therefore disappeared as a costume, the fool continued to adorn himself with the bells, which made him even more ridiculous. By now at the latest a negative context had prevailed, which almost prescribed the bells as a fool's symbol. As a sign of evil, they stood for seduction, hollow jingling and for the vice of loquacity, which was already mentioned in the 9th century by Rabanus Maurus . The latter justified this with the Pauline word 1. Cor. , 13, 1: Si linguis hominum loquar et angelorum caritatem autem non habeam factus sum velut aes sonans aut cymbalum tinniens (If I spoke in the languages of people and angels, but if I didn't have love (= charity), I would be ore or a ringing bell.) Translated this means: "Without charity my praise and my speech is nothing but chatter." Here the circle of fools closes again: the fool pursues amor carnalis and self-love, he does not know charity; it stands for lovelessness and self-satisfied chatter. Because of this allegory, the fool was literally showered with bells at the end of the 15th century: They were attached to all corners of the garment, to the quirk, to the cowl, etc. Even today you don't see a carnival jester who isn't wearing bells or rollers (round bells with a sound slot) somewhere. The baroque Narros in the Swabian-Alemannic Carnival wear many roller belts, and in the Tyrolean Carnival, the Scheller and Roller embody exactly this medieval tradition.

Metaphorical attributes

Mirror and fool mirror

The mirror is a further development of the quirk. While the fool, in love with himself, initially still plays with his replica doll = quirk, from the 15th century at the latest he also looks at himself in the mirror. According to medieval ideas, people who were portrayed with a mirror were considered blinded and blind to God. Here, too, the fool reappears as the one who denies God. In connection with the fool's closeness to death, in some illustrations a skull grins at him instead of his own face. Another variant of the fool's mirror, which explains itself, can be found at the town hall of Nördlingen:

Later, the fool's mirror is a symbolic term, namely the mirror that the court fool holds up to the prince and the fool of the world through his speeches so that they should recognize their stupidity and inadequacy. In this sense, the term has a positive connotation, as a necessary and useful critique. The instructive literary genre of the mirror in antiquity and the Middle Ages is directly related to this meaning . The term lives on today as the name of carnival club magazines, for example, but also in literature and film, see: Narrenspiegel (disambiguation).

Hourglass

The hourglass is in medieval illustrations actually more common with the death , usually in the form of a skeleton represented. However, since the fool had an immediate relationship to death through his role as a reminder of vanitas , he occasionally appears with an hourglass in hand, which reminded the viewer that at some point the glass will have expired and life will end ( memento mori ). This also explains why the figure of death was often depicted in the typical fool's robe with dog ears and a cowl. B. in dances of death .

Order chain

Regarding the origin of the fool's dress, the fool, especially the court jester, appears from time to time with an order chain around his neck. The order chain was often with the coats of arms of the lord, to whom the fools were subordinate, and thus represents the affiliation of the fool to his master.

loaf

In the early Psalter illustrations for Psalm 52 (Luther translation of Psalm 53), the fool often appears with a bread in his hand marked with a cross. In some illustrations he is just about to bite the bread. The fool with the bread attribute is based on verse 5 of Psalm 52 (53): “Nun scient omnes qui operantur iniquitatem qui devorant plebem meam ut cibum panis?” (“Have no knowledge of those who commit crimes that devour my people but eat they bread? "), possibly even more so on the" bread of godlessness "from the book of Proverbs 4, 17: " Comedunt panem impietatis - you eat the bread of iniquity ". The fool stands here, strictly true to his denial of God, as a wrongdoer who tries to dissuade God's people from their right faith and therefore "eats them up like bread".

Fool sausage

The fool's sausage is a sausage-shaped, elongated leather bag (30 to 50 cm long), stuffed with horsehair, reminiscent of a phallus . The fool's sausage characterizes the fool as one who is oriented towards carnal lusts, both in terms of gluttony and sexual desire. In addition, the fool's sausage serves as a percussion instrument, e.g. B. for self-defense.

Foxtail

From around 1450, the fool in Psalm 52 carried another utensil in his hand: a kind of frond attached to a stick. Other clear examples from later times prove that this is actually a foxtail . The fox tail, which the fool had partly attached to the cowl - just as many fools of the Swabian-Alemannic carnival still have today - has had a negative meaning since late antiquity , just like the fox in general . Christian theologians equated the fox with the devil or interpreted him as a deceiver of people guided by the principle of evil, as an image of the heretic or as the embodiment of the sinner per se. He also stood for individual vices such as avarice, deceit and excess. Since the 15th century, the fox as a whole, but only its tail, has been a symbol for these meanings, so Sebastian Brant made the fox's tail a theme in the Ship of Fools as well as on other single-sheet prints . At Brant, the meaning of the foxtail as a symbol of lying chatter and defamation has expanded. For this reason, in the late Middle Ages, cheaters and dodgy people were called "fox tails". The often widespread assumption that today's carnival jester wears the foxtail as a sign of his cunning is wrong in view of this meaning. An example from the visual arts is the painting The Rommelpotplayer by the Flemish painter Frans Hals .

Scepter-like sticks, "weapons"

Club

The meaning of the club , also known as the fool's piston, that the historically early fool wields in his hand is unclear. This attribute may also go back to a biblical passage ( Proverbs 19, 29: The stick is held ready for the mockers, and a beating for the back of the foolish ). In the second half of the 13th century the club developed more and more antithetically to the scepter of King David.

Quirk

With the development of the club into the antithesis of the king's scepter, the club developed into a quirk ; the tip of the club got a head about the size of a fist, which the fool carries in front of him like a kind of doll (cf. French marionette = doll). Various sources indicate that this doll symbolizes the portrait of the wearer; so he carries his own portrait before him. The result is that the fool is limited to his own self, almost in love with himself; he lacks charity (lat. caritas ) and especially love for God. Thus, the quirk is another attribute that underlines the fool type with the slogan Non est deus .

bladder

Referring to the spherical bread into the fool into biting the psalteria or sometimes only holds in his hand a round object in the Dutch painting of the late Middle Ages is often called Sottebolle designated as fools Bollen , with Bollen a round, spherical, lump-like object means.

Already in the 14th century a change in understanding of this round bread was announced. While the fool continues to bring a round object to his mouth, the antithetical Christ also holds a round object in his hand. Even in Carolingian times, this object in the hand of Christ would have been interpreted as a host and thus as a counterpart to the bread of fools, but from the 10th century the Messiah increasingly appears with an imperial orb , symbolizing the rule over heaven and earth. If one proceeds from the predominant antithetics in psaltery illustrations, then the round object of the fool can no longer be bread, which is also confirmed by the fact that since the 15th century this object is no longer shown in brown but in blue. The bread became the glass sphere or bubble of vanitas that often appears in other iconographies . This is confirmed by clear later engravings, for example in a copper engraving from the end of the 16th century in the ball or bubble of the fool: Vanitas vanitatum et omnia vanitas (everything is void and vain). This closes the circle to the god-negating fool who is close to death and also points out that man is perishable. The vanitas bubble is still a tradition in today's Carnival , not a few carnival jesters appear in southwest Germany with an empty pig's bladder ("Saubloder") in their hand and indicate the essence of all folly: Vanitas. It is also significant that the French fou (= crazy) and the English fool (= fool) arose from the Latin meaning for "empty sack" or "balloon" ( follis ) .

Carbachute

A carbatsche is a whip made of leather straps or hemp rope with a short wooden handle.

The name either comes from the Polish karbacz = leather whip or comes from the Turkish name Kurbatsch. Karbatschen are now mainly sold by ropemakers in the Upper Swabian region. The production has hardly changed for centuries.

The carbatsche was originally used to drive cattle. Today it can only be found in the Upper Swabian Fasnacht (Fasnet), such as in Weingarten (Württemberg) at the Plätzlerzunft or in Stockach.

Cot

Another symbolic weapon of the fool is the cot , also known as a "clap". It consists of cardboard folded in a Z-shape , which produces a loud bang when opened, but practically no pain. The cot is common today in carnival and is also known as the "weapon" of the puppet figure.

Web links

literature

- Werner Mezger , Irene Götz : fools, bells and quirks. Eleven contributions to the fool's idea (= cultural-historical research. Vol. 3). 2nd, improved edition. Kierdorf, Remscheid 1984, ISBN 3-922055-98-2 .

- Werner Mezger: fool's idea and carnival custom. Studies on the survival of the Middle Ages in European festival culture (= Konstanz Library. Vol. 15). Universitätsverlag, Konstanz 1991, ISBN 3-87940-374-0 (At the same time: Freiburg (Breisgau), University, habilitation paper, 1990).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Johann Georg Krünitz, Friedrich Jakob Floerke, Heinrich Gustav Floerke, Johann Wilhelm David Korth, Ludwig Kossarski, Carl Otto Hoffmann: Oekonomische Encyclopaedie or general system of state urban household and agriculture in alphabetical order by Johann Georg Krünitz [continued from - Vol 73-77: Friedrich Jakob Floerke, Vol 78-123: Heinrich Gustav Flörke, Vol 124-225: Johann Wilhelm David Korth, partly Ludwig Kossarski a. Carl Otto Hoffmann, 226-242: Carl Otto Hoffmann] . Poculi, 1806, p. 275.