Tablas de Daimiel National Park

|

Tablas de Daimiel National Park

|

||

|

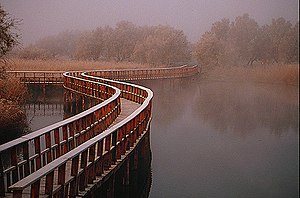

Visitor footbridge in the Tablas de Daimiel |

||

| location | Castile-La Mancha , Spain | |

| surface | 30.305 km² | |

| WDPA ID | 4750 | |

| Geographical location | 39 ° 9 ' N , 3 ° 40' W | |

|

|

||

| Sea level | from 601 m to 617 m | |

| Setup date | 1973 | |

| administration | National park administration in Daimiel | |

The Spanish national park Tablas de Daimiel is located in the autonomous region of Castile-La Mancha in the area of the municipalities of Daimiel and Villarrubia de los Ojos. The protected area, which is quite small for a national park, protects one of the last remaining floodplains in central Spain. The area was originally 1,928 ha, since 2014 it has been 3,030.5 ha. Due to the lack of water, which was mainly due to the use of groundwater for irrigation, the area was temporarily dried out.

history

As early as 1325, Don Juan Manuel mentioned the suitability of the banks of the Cigüela River for pickling . In 1575, Philip II described the Tablas de Daimiel in his Relaciones Topográficas and ordered “to take good care of them”. Hunting for waterfowl has a long tradition in the Tablas de Daimiel , where General Juan Prim hunted in 1870 and King Alfonso XII in 1875 .

In 1956, a law on the drainage of the wetlands along the rivers of the Mancha ( Ley de Desecación de Márgenes del Gigüela, Záncara y Guadiana ) was promulgated. It remained in force until the National Park was established in 1973. During these years canals were built and hectares of wetlands were drained. The drainage of the wetlands along these rivers would have had an impact on the entire region, characteristic water areas such as the Ojos del Guadiana and the Tablas de Daimiel would have disappeared.

At the beginning of the 1960s, the canalization of the rivers of the Mancha progressed ever faster. At that time, the uncontrolled tapping of groundwater for irrigation began, which was to become the main problem in the 1970s.

The Tablas de Daimiel were declared a national park in 1973, a biosphere reserve in 1981 and a “wetland of international importance” according to the Ramsar Convention in 1982 . Since 1988 they have been a Special Protection Area according to the EU Birds Directive (abbreviated to ZEPA in Spain).

The tablas had practically dried up by 2005. As a result, underground peat stores had caught fire. Years of drying out caused cracks to form in the soil, through which peat beds came into contact with atmospheric oxygen, causing spontaneous combustion. In this way, an underground smoldering fire started , the exhaust gases of which rose to the surface through the cracks in the ground. As a result, the tablas released more carbon dioxide than they stored. At the beginning of February 2010, the fire was extinguished by weeks of rain and water from two reservoirs.

Between 2004 and 2013, the national park authority replaced more than 4.4 million m³ of water abstraction rights and bought 1,904 hectares of land in the vicinity of the park. In January 2014, the national park was expanded to include those acquired properties that are directly adjacent. This increased its total area by 1,102.5 ha to 3,030.5 ha.

Hydrology

The water supply of the Tablas de Daimiel is related to the large La Mancha Occidental groundwater under the western part of the Mancha , which was previously called " Aquifer 23" and is now called "Hydrogeological Unit 04-04". The Tablas de Daimiel and the Ojos del Guadiana are located on the southwestern edge of this aquifer. Under natural conditions, the water in the aquifer flows slowly westwards and comes to the surface at the Ojos del Guadiana. The uncontrolled withdrawal of water significantly lowered the groundwater level, so that no more groundwater has fed the Ojos del Guadiana and the Tablas de Daimiel since about 1984. The flow conditions have reversed, water from the Tablas de Daimiel seeps into the karst underground and feeds the groundwater. The Tablas de Daimiel were practically dried up for the first time in 1995; from 2005 to 2010 they were again without water. The heavy rains in 2010 ensured that the Tablas de Daimiel reached their peak again in 2010 and 2011. The high water level is deceptive, however, as the karst subsoil, which has dried out for a long time, can still absorb a lot of water.

The Guadiana River is closely related to the La Mancha Occidental groundwater body . The Ojos del Guadiana were the most important tributary on the middle reaches of the Guadiana. The river carried water all year round, but then dried up for a long time. Since 2010 it has also been running water again.

The second important tributary of the Tablas de Daimiel, the Cigüela, has a fluctuating water level even under natural conditions. The changes are not quite as serious here as in the Guadiana, but the Cigüela also delivers less water today. One reason is that ponds were created on its upper reaches for hunting in order to attract waterfowl.

An important contribution to the biodiversity in the Tablas de Daimiel is made by the fact that the two main tributaries have significantly different salinity. While the Guadiana has fresh water, the water from the Cigüela is more brackish or salt water; it rises near Cuenca and passes the region around Alcázar de San Juan , in which some very salty lagoons can be found. In the Tablas de Daimiel there are therefore fresh, salt and brackish water areas in a very small space.

Ecological importance

The Tablas de Daimiel are the last relic of the river-accompanying wetlands in Spain, in which a river overflows its banks at its middle course. Such wetlands occur above all on low slopes and where there are shallow depressions near the river.

The wetlands at the confluence of the Guadiana and its Cigüela tributary are among the most important in Spain due to their fauna and flora. They are also used by a large number of migratory birds such as ducks and geese for a stopover.

They get their water from two rivers with different characteristics: the salty Gigüela draws its water from the Cabrejas swamps in the highlands of the province of Cuenca , while the Guadiana comes from its "ojos" springs, which are about 15 km north of the national park near Villarrubia de los Ojos lie, "sweet" water brings them up.

vegetation

Fed by the fresh water of the Guadiana, extensive areas of reed ( Phragmites australis ) were created, while the salty water of the Cigüela allows other aquatic plants, especially the rush blade ( Cladium mariscus ), to flourish. The extensive stocks of the rush edge represent its largest occurrence in Western Europe. In the flatter areas you can find various types of cattails , the braided cornices ( Scirpus lacustris ), beach cornices (syn .: Scirpus maritimus ) and rushes .

The underwater meadows formed by charophytes are among the most characteristic plant populations of the national park , where chandelier algae ( chara ) predominate. They form almost continuous stands on the flooded areas.

Occasionally, the French tamarisk thrives in elevated places as the only tree species found in the park.

Wildlife

The migratory birds in the park include the purple heron ( Ardea purpurea ), gray heron ( Ardea cinerea ), little egret ( Egretta garzetta ), night heron ( Nycticorax nycticorax ), the bittern ( Botaurus stellaris ), red puffer ( Netta rufina ), shoveler ( Anas clypeata ) , Wigeon ( Anas penelope ), pintail ( Anas acuta ), teal ( Anas crecca ), tree falcon ( Falco subbuteo ), grebe ( Podiceps auritus ), black-necked grebe ( Podiceps nigricollis ), stilt ( Himantopus himantopus ), the cistas warbler ( Cistensänger ( Cistensänger ) and the bearded tit ( Panurus biarmicus ).

One of the sedentary animals is the jackdaw crab ( Austropotamobius pallipes ), which used to be very common and whose catch was an important source of income for the inhabitants of Daimiel and which is now almost extinct in the region. Since the introduction of the pike ( Esox lucius ), the stocks of barbel ( Barbus barbus ), carp ( Cyprinus carpio ) and chub ( Leuciscus cephalus ) have declined so much that they could disappear from the park entirely.

In spring and summer you can find amphibians and reptiles such as the European tree frog ( Hyla arborea ), sea frog ( Rana ridibunda ), common toad ( Bufo bufo ) and fire salamander ( Salamandra salamandra ), as well as the "water snake" grass snake ( Natrix natrix ) and viper snake ( Natrix maura ).

Mammals that occur in the national park are, for example, the European polecat ( Mustela putorius ), red fox ( Vulpes vulpes ), otter ( Lutra lutra ) and the eastern water vole ( Arvicola amphibius ), wild rabbits ( Oryctolagus cuniculus ), cap phase ( Lepus capensis ) live in the vicinity Mouse weasel ( Mustela nivalis ) and wild boar ( Sus scrofa ).

Also worth mentioning are the occurrence of harrier ( Circus aeruginosus ), Coot ( fulica atra ), Teichralle ( Gallinula chloropus ), Mallard ( Anas platyrhynchos ), Schnatterente ( Anas strepera ), Kingfisher ( Alcedo atthis ) Moorente ( Aythya nyroca ) and Tufted ( Aythya fuligula ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ In Spanish, the tablas de río are wetlands that accompany rivers and generally arise due to a slight gradient. Real Academia Española Diccionario de la Lengua Española , search term Tabla

- ↑ Spanish Ministry of the Environment: Tablas de Daimiel: Historia , accessed on January 13, 2015.

- ↑ Reinhard Spiegelhauer, tagesschau.de: Spain's wetlands: Huge crevices in the ground ( Memento from November 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The World: Don Quixote's Home Becomes a Desert , October 23, 2009.

- ^ Hamburger Abendblatt: National park fire extinguished in Spain , news from February 1, 2010.

- ↑ Boletín Official del Estado: Acuerdo de Consejo de Ministros de 10 de enero de 2014 por el que se amplían los límites del Parque Nacional de las Tablas de Daimiel por incorporación de terrenos colindantes al mismo , January 27, 2014.

- ↑ Manuel García Rodríguez, Juan Almagro Costa:Las Tablas de Daimiel y los Ojos del Guadiana: Geología y evolución piezométrica( Memento of the original from May 3, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF file; 1.30 MB) . Revista Tecnologí @ y Desarollo, Escuela Politécnica Superior, Universidad Alfonso X el Sabio, Vol. II, 2004

- ↑ Fabián Martínez Redondo: Pasado, Presente Y Futuro De Las Tablas De Daimiel (Y Ii) ( Memento of the original from April 26, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , October 2002.

Web links

- National Park Tourist Information Office (Spanish)

- Spanish Ministry of the Environment: Las Tablas de Daimiel . (Spanish)

- World Database on Protected Areas - Tablas de Daimiel National Park (English)

- Reiner Wandler: The national park is threatened with desertification . taz of June 24, 2008

- Reiner Wandler: Wetlands on dry land (PDF file; 669 kB). Of course, 10-2006

- www.spain.info: Tablas de Daimiel National Park (German)