Organ transplant in China

Organ transplants were first performed in China in the 1960s . With over 13,000 transplants in 2004, China has one of the most extensive organ transplant programs in the world and operates advanced transplant surgery in the field of transplantation, including face transplants with bones.

Although involuntary organ harvesting is prohibited under Chinese law, an ordinance was passed in 1984 that legalized organ harvesting from executed criminals if the perpetrator himself or his relatives had given consent to organ removal. However, the use of the organs of executed criminals raised international concerns about the possible ethical abuse of consent forms under coercion and influence, so that the practice was condemned by medical professionals and human rights organizations in the early 1990s. When a Chinese surgeon seeking asylum testified in 2001 that he had been involved in organ harvesting himself, the objections raised earlier became relevant again.

In 2006, allegations surfaced that large numbers of Falun Gong practitioners were killed for their organs in order to supply organs for China's transplant market. An initial investigation by Canadian human rights attorney David Matas and former prosecutor and Canadian state secretary David Kilgour revealed that the origin of 41,500 organs between 2002 and 2005 could not be identified. The investigation concluded that "involuntary organ harvesting has occurred on a large scale from Falun Gong practitioners and is still happening." Another study by China analyst and investigative journalist Ethan Gutmann led to similar results in 2008 and was published in book form in 2014. Gutmann estimates that around 64,000 Falun Gong practitioners were killed for their organs between 2002 and 2008.

China's Deputy Health Minister Huang Jiefu confirmed in December 2005 that the practice of organ harvesting is widespread from executed criminals. In 2007 regulations were passed prohibiting the commercial trade in organs. The Chinese Medical Association agreed not to use prison inmates' organs for transplants, except for direct relatives of the deceased. In 2008, a registry of liver transplants was established in Shanghai, along with a nationwide plan to include the relevant information in the driver's licenses of voluntary organ donors.

Despite these initiatives, China Daily reported in August 2009 that approximately 65% of the organs transplanted were still from death row inmates. However, the convicted criminals were labeled an "unsuitable source for organ transplants" by Deputy Health Minister Huang Jiefu. In March 2012, he announced the trial of the first post-death organ transplant program jointly operated by the Red Cross and China's Ministry of Health in ten pilot regions. In 2013, Huang Jiefu again changed his mind about the use of prisoners' organs and agreed to donate organs from death row inmates to be included in the new computer-based distribution system. In 2014, Huang Jiefu published that as of January 2015, organs from executed prisoners will no longer be used. Amnesty International's Gosteli Hauser stated in October 2015 that organ harvesting from those executed was still not prohibited by law in China. And according to the medical ethicist Norbert Paul and the pharmacologist Huige Li, Huang's statements do not sound like an end to organ removal from the executed.

prehistory

The first experiments with human organ transplants in medicine took place at the beginning of the 20th century. The pioneer was the French surgeon Alexis Carrel . Successful transplants could finally be carried out after the Second World War. However, China did not begin organ transplants until the 1960s, which were initially carried out rarely, but skyrocketed from 2000 and peaked in 2004 with over 13,000 organ transplants. As the International Committee of the Red Cross reported, many lives have been saved by China's establishment of a transplant program, including some deaths from infections and hepatitis. Although organ transplants fell below 11,000 in 2005, according to official figures, China still has one of the largest transplant programs in the world. In addition, China is also engaged in advanced surgery such as the first face transplant including muscles and bones performed by Professor Guo Shuzhong.

Although the topic of "organ donation" is discussed in western countries and generally viewed positively by the population, there is still strong reluctance among the Chinese population to voluntarily donate organs, as this does not correspond to the traditional and cultural values of China. A symbolic life force is assigned to the kidneys and hearts, and the body of the deceased is to be buried intact. Illegal organ donation is prohibited under Chinese law as it is in Western countries.

The problem of finding enough donor organs does not only affect China, however, as most countries have a higher demand than organs are available. This worldwide shortage of organ transplants led some nations, such as India, to start trading human organs. Reports of the sale of organs from executed criminals in China have surfaced around the world since the 1980s. In 1984, China finally legalized organ harvesting from convicted criminals if the family gives consent or if the corpse is not claimed. At the same time, the development of the immunosuppressant cyclosporine A, which was able to suppress the body's rejection reaction much better, led to organ transplants becoming usable for more people.

Milestones

China performed the first living kidney transplant in 1972, and in 1981 the first successful allogeneic bone marrow transplant was performed on a leukemia patient.

The first verifiable liver transplant from a living donor was performed in 1995, seven years after the first ever liver transplant, which took place in São Paulo, Brazil. Between January 2001 and October 2003, 45 patients in five different hospitals received liver transplants from living donors. Doctors from Xijing Hospital of the Fourth Military Medical University documented three cases of liver transplants from living donor organs in 2002. Between October 2003 and July 2006, the West China Hospital in the University Hospital of Sichuan University carried out 52 liver transplants from living donors alone. In October 2004, two liver transplants were performed from living donors with complex blood vessel anatomy at the Transplant Center of the University Hospital of Peking University.

Chinese media reported in 2002 that Zheng Wei at Zhejiang University transplanted a whole ovary to 34-year-old Tang Fangfang from her sister's sister.

In 2003 a patient died of a brain death caused by the fact that his ventilation had been switched off. After this incident became known, there were changes in the field of medical ethics and transplant legislation, which made it possible to carry out the first successful organ transplant with organs from a brain death patient.

Xijing Military Hospital performed a face transplant on Li Guoxing in April 2006 that restored his cheek, upper lip, and nose. These had been mutilated by a collar bear when Li tried to protect his flock of sheep.

The first successful penis transplant was performed at the Guangzhou Military Hospital in September 2006. The 44-year-old patient's penis was transplanted from a brain-dead 22-year-old. The operation was successful, but had to be reversed 15 days later, as both the patient and his wife had suffered psychological trauma from the operation. Jean-Michel Dubernard, who became known for performing the world's first face transplant, commented on this incident that it raised many questions and was criticized from some quarters. He also pointed out the prevailing double standard: "I cannot imagine what reactions there would have been from the medical profession, ethics experts and the media if a European surgical team had performed the same procedure."

International concerns

Prisoners sentenced to death as organ sources

In the early 1970s, China began organ transplants using organs from executed inmates. Other sources were also tried, such as living organs from brain-dead patients, but there were no legal regulations for them, which restricted this area as an organ source. Therefore, in 2007, Doctor Klaus Chen said that the predominant source of organs was still the executed inmates.

World Medical Association

As early as 1985, the World Medical Association in Brussels condemned the trade in human organs over concerns that poorer countries could take advantage of the lack of sufficient donor organs in wealthy countries to build up a lucrative organ trade with richer countries. In 1987 and 1994 the World Medical Association in Stockholm repeated its concerns and condemnation of the purchase and sale of human organs.

Also in 1987, the World Medical Association in Madrid condemned the practice of using organs from executed prisoners, as it was basically not possible to find out whether prisoners had given their consent to organ donation voluntarily. Increasing international concerns ultimately led medical professional associations and human rights organizations to join the condemnation of this practice in the 1990s and question the way in which organs were obtained.

In May 2006, the World Medical Association at its council meeting in Divonne-les-Bains, France, again condemned the practice of organ use by inmates and called on the Chinese Medical Association to ensure that Chinese doctors are not involved in the removal of organs for transplantation from executed Chinese inmates. At the same time, the World Medical Association passed a resolution emphasizing the importance of the free and informed choice of organ donation. The resolution reiterated an earlier guideline that regards detainees as not being able to make a free choice and whose organs are therefore not to be used for organ transplants.

World health organization

In the same year the WHO began to draft international recommendations (WHA44.25) regarding human organ transplants, which were finally adopted in 1991 as the "WHO Guiding Principles on Human Organ Transplantation". However, since these Guidelines were by no means legal in nature, the international community still had no means of preventing China from continuing to trade in human organs.

United States of America

In 1995, the United States Senate Foreign Relations Committee held a hearing about the human body part trafficking in China. A large amount of evidence was cited at the hearing from various sources, including Amnesty International, the BBC and human rights activist Harry Wu, who presented documents to the Chinese government.

International medical associations

In 1998, the World Medical Association, the Korean Medical Association, and the Chinese Medical Association agreed to work together to investigate how to end these undesirable practices, but China withdrew its cooperation in 2000.

Amnesty International

Amnesty International reported that the police, courts and hospitals were involved in organ trafficking and that mobile execution cells called "death trucks" were being used. With the death penalty imposing between 1770 (official number) and 8000 (Amnesty International) annually in China, Amnesty speculated that China's refusal to abolish the death penalty could be explained by this profitable organ trafficking. Since the bodies of those executed are generally cremated before relatives or witnesses can see them, speculation about the removal of organs has led to speculation.

Harry Wu and the Laogai Research Foundation

In June 2001, Wang Guoqi, a Chinese surgeon and burn specialist, turned to Harry Wu, a Sino-American human rights activist who had spent 19 years as a political prisoner in Chinese prisons. Wu headed the Laogai Research Foundation, which campaigned against the use of organs from Chinese inmates. Wang had applied for political asylum and asked Wu to help him prepare a written testimony to the US House of Representatives. In it, Wang stated that at the Tianjin Paramilitary Police General Brigade Hospital, he removed the skin, corneas, and other tissues for the organ market from over 100 executed inmates, and that at least one detainee was still breathing during the operation. Wang also said that he had seen other doctors harvest organs from executed prisoners, and that the hospital sold these organs to foreigners. When asked about Wang's credibility, Wu said he had gone to great lengths to verify Wang's identity and that both he and members of Congress found the doctor's testimony to be very credible. Republican MP Ileana Ros-Lehtinen later tabled a bill to prohibit Chinese doctors from receiving training in transplantation in the United States.

China's announcements and contradictions

Although the Chinese government still claimed in 2016 that there are up to 10,000 transplants performed annually in China, there were 6,000 kidney and liver transplants in 2003 and 13,000 in 2004, according to Deputy Health Minister Huang Jiefu. China Daily reported a total of 20,000 transplants performed annually in 2006 and 2007.

In 2005, Huang hit the headlines in the Chinese media as China's most famous liver transplant surgeon when he traveled to Xinjiang to perform a highly complex autologous liver transplant. The patient's liver was removed, cancerous tissue excised, and then re-transplanted. As a safeguard for this innovative and risky procedure, Huang ordered two additional livers from Chongqing and Guangzhou by telephone the day before, which were found within a few hours and delivered one day before the operation. Since a removed liver has to be transplanted within 15 hours and the operation did not take place until 60 hours later, investigators assumed that live prisoners were brought in, who were available for organ removal on demand. Such incidents are unthinkable in systems where organs are voluntarily donated, scarce and allocated as needed, according to Wendy Rogers, medical ethics expert at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia.

In December 2005, Huang Jiefu first admitted that the use of organs from executed prisoners was widespread and that up to 95% of all organ transplants come from executions. At the same time, he promised to take steps to end this abuse. Huang publicly described this type of organ procurement several times as “profit-oriented, unethical and violates human rights”. Despite this promise, no changes followed, so that in 2006 the World Medical Association once again asked China to stop using prisoners as organ donors.

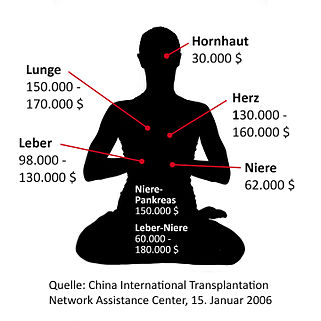

On January 15, 2006, transplant organs were offered on the China International Transplantation Network Assistance Center website for the following prices:

- Kidney $ 62,000

- Liver $ 98,000-130,000

- Liver-Kidney $ 60,000-180,000

- Kidney-Pancreas $ 150,000

- Lungs $ 150,000-170,000

- Heart $ 130,000-160,000

- Cornea $ 30,000

- For patients on dialysis for ten years, the price increases by $ 20,000.

- For liver, heart, and lung transplant patients, the price increases by $ 80,000 in the event of a complication.

The transplant center also cited the availability and selection of organ donors: “It only takes one month for a liver transplant, a maximum of two months. For kidney transplants, it takes a week to find a suitable donor, a maximum of a month. ”The organ offer was also provided with a guarantee:“ If the doctor determines during the transplant that the donor organ is unsuitable, the patient will be given another organ donor and the operation was repeated within a week. "

However, these are not fixed prices, but vary in the event of insufficient availability. Der Spiegel reported in 2013 that when asked for a kidney, another Chinese transplant agency replied that it was no problem to get a kidney, only the price had risen slightly, so that a kidney transplant costs $ 350,000, albeit including accommodation.

Chinese media reported over 20,000 organ transplants in 2006. This number was downplayed after the Kilgour Matas investigation report was published.

On March 28, 2006, Foreign Ministry spokesman Qin Gang said, "It is a complete fabrication ... to say that China is forcibly taking organs from people sentenced to death to use for transplant purposes." China has strict laws and guidelines. Donors, recipients and hospitals should strictly follow the laws and guidelines in this area.

In April 2006, Time reported that an organ broker in Japan had organized 30 to 50 organ transplants from executed Chinese prisoners annually. She also stated that prior to President Hu Jintao's state visit to the United States, the 800-member British Transplant Society had also criticized the use of organs from executed Chinese prisoners in transplants, as it was impossible to verify whether the prisoners gave their consent.

European Parliament

In June 2006, Vice-President of the European Parliament Edward McMillan-Scott told the Yorkshire Post that he believed that nearly 400 hospitals in China are involved in organ trafficking and that websites offer kidney transplants for $ 60,000. Administrative staff told inquiring people, "Yes, it's Falun Gong, so these [organs] are clean."

Covert investigation

In September 2006, BBC News reported undercover Rupert Wingfield-Hayes who was negotiating a liver transplant with doctors and a transplant broker at Tianjin First Central Hospital . On the one hand, he was told that a liver could be obtained within three weeks, and on the other hand, that the organs had come from executed prisoners. Last year the hospital reportedly performed 600 liver transplants, each organ selling for £ 50,000 or more.

Organ donations from prisoners sentenced to death

theory and practice

Although China’s Deputy Minister of Health Huang Jiefu admitted in 2005 that organs from death row inmates were used for organ transplants, neither China’s official statement of 1,770 prisoners executed annually nor Amnesty International’s estimated number of up to 8,000 executions annually that a total of 120,000 organ transplants had been performed in China by 2010.

Doubts about the exclusive use of death row inmates arose due to restrictive factors such as:

- Not all executed prisoners are eligible . In China, the prevalence rate of hepatitis B within the population is between 9 and 10%, and in prisons the proportion is even higher. These prisoners cannot be used for organ transplants, thereby reducing the number of possible organ sources.

- Organs must match the recipient . The blood type and tissue types between the organ donor and organ recipient must be compatible, which further reduces the number of possible organ sources. According to Professor Li from Gutenberg University Mainz, the blood and tissue compatibility between unrelated people is 5%.

- Until 2013, organs for transplantation could only be used locally . Since there was no national organ donation and distribution system in China until 2010, organs from executed prisoners could only be distributed locally, which limits national availability.

- Illegal practice of organ harvesting . Organ removal without the voluntary consent of the organ donor is illegal. According to international standards, organs from executed prisoners may not be used because it cannot be guaranteed that they will give voluntary consent to organ donation. Therefore, such organ uses have not been distributed nationwide.

- Time factor . Removed organs must be transplanted within a few hours. The execution of prisoners could theoretically occur when a patient needs an organ, but Chinese law requires executions to be carried out within seven days of the death sentence.

These factors limit the use of organs that can be used annually by death row inmates, so the number of 120,000 organ transplants by 2010 cannot be explained by the estimated number of inmates executed. However, to this day (2016), transplant centers in China continue to offer organs from living younger donors under 40 years of age that are available within 3 to 5 days.

Alleged organ harvesting from Falun Gong practitioners

In 2006, two Canadian human rights lawyers, the former prosecutor and the Canadian state secretary, investigated the allegations that China was supplying its organ transplant industry with organs from living Falun Gong practitioners who are being harvested and whose remains are being burned in the hospital's crematorium David Kilgour and immigration attorney David Matas . In July 2006, they released their investigations to the public and, in their investigation report, questioned the source of 41,500 organ transplants that had taken place between 2000 and 2005. Their conclusion from the evidence gathered was that since 1999 the Chinese government and its state organs have killed a large but unknown number of Falun Gong prisoners of conscience in China's hospitals, detention centers and people's courts.

The facts that Kilgour and Matas themselves compiled were detailed in their investigation report. One of the pieces of evidence deals with the extremely short waiting time for organs in China, unlike in other countries, which indicates that organs can be provided as needed and that this is only possible if the organ donor is available on call. Another indication is the sudden surge in annual organ transplants in China that coincides with the start of the persecution of Falun Gong . In 2007, Kilgour and Matas published an expanded version of their investigation report, which contains additional facts to support the previous allegations. In 2009 her research report was published as a book.

In 2006, human rights activist Harry Wu questioned the allegations made by Falun Gong and that Falun Gong practitioners were the target of large-scale organ harvesting. This despite the fact that he and his Foundation had already described the testimony of surgeon Wang Guogi to the US House of Representatives as "very credible" in 2001 that prisoners sentenced to death are being killed on demand for their organs. International human rights attorney David Matas disagreed, arguing that Harry Wu's 2006 article reflected his views from a March 21 letter he had published two months before his own investigation was closed, so his testimony is not based on his own full investigation could. As a medical layperson, Harry Wu also described the extent of organ harvesting as “technically impossible”, although according to medical experts this is very possible. Mohan Rajan described the operation time as only 20 minutes. Furthermore, Matas found that it was unfair to the witnesses and the truth-finding process to call the statements lies without having questioned the witnesses themselves.

The Kilgour-Matas investigative report led the two largest organ transplant hospitals in Queensland , Australia to call on the Chinese government to comment on the allegations. In December 2006, in the absence of evidence from the Chinese government, the hospitals stopped training Chinese surgeons in organ transplants and banned joint organ transplant research programs with China.

In July 2006 and again in April 2007, the Chinese embassy in Canada denied the organ harvesting allegations and insisted that China was following World Health Organization principles and prohibiting the sale of human organs without the written consent of organ donors.

In August 2006 and January 2007, United Nations Special Rapporteurs urged the Chinese government to comment on the allegation of organ harvesting from Falun Gong practitioners and the short waiting times for appropriate organs, organ sources, and the correlation between the sudden increase Explaining organ transplants and the start of the persecution of Falun Gong practitioners, but no response was made.

On March 20, 2007, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture Manfred Nowak presented his annual report at the 4th Human Rights Council meeting in Geneva, directly referring to the organ harvesting from Falun Gong practitioners. In addition, Novak stated that in March 2006, shortly after the Kilgour-Matas investigation report was published, the Chinese government presented a bill that bans the sale of human organs, requires written consent from organ donors and limits transplants to institutions that support the Can prove organ source. This law is said to have entered into force on July 1, 2006. However, Manfred Novak pointed out that contrary to what the Chinese government claims, “to this day (March 2007), Chinese law allows organs to be bought and sold; does not require the organ donor's written permission; there are no restrictions for institutions to participate in organ procurement or transplantation; there are no requirements that the institutes involved in organ transplants must provide evidence of the legal sources of the transplanted organs; and there is no requirement that transplant ethics committees must pre-approve all transplants. "

The Chinese government did not respond to or refute the allegations in 2006 or 2007. Therefore, in May 2008, the two United Nations Special Rapporteurs, Asma Jahangir (freedom of religion or belief) and Manfred Nowak (torture), again urged the Chinese authorities to provide an appropriate statement and to reckon organ donors for the sudden increase in the number of organ donors since 2000 To name a few organ transplants in China. Once again, the Chinese government failed to provide a clear explanation.

In September 2012, the Foreign Affairs Committee of the United States House of Representatives held a hearing on organ harvesting from prisoners of conscience in China. During the hearing, investigative journalist Ethan Gutmann described his interviews with former Chinese prisoners, surgeons and nurses with knowledge of organ harvesting practices in China and found clear evidence that Falun Gong prisoners of conscience were being held in China's prisons, labor camps, etc. without their consent to their medical examination Organs including blood sampling were subjected. Damon Noto, spokesman for the DAFOH doctors' organization, testified that up to 60,000 Falun Gong prisoners of conscience have been murdered for their organs and that there has been an exponential increase in transplants in China since 2000, with the onset of the suppression of Falun Gong correspond.

In 2012 the book "Staats-Ore: Transplantation Abusive in China" by David Matas and Torsten Trey (DAFOH) was published, containing treatises by medical professionals such as Gabriel Danovitch, Professor of Bioethics Arthur Caplan, Cardiac Surgeon Jacob Lavee, Ghazali Ahmad, Professor Maria Fiatarone Singh, Torsten Trey as well as investigative journalist Ethan Gutmann and human rights attorney David Matas , who relate to the crime of organ harvesting in China.

According to his testimony before the House of Representatives in 2012, the investigative journalist Ethan Gutmann published his own independent research in book form in 2014. Gutmann compiled in-depth interviews with former prisoners in Chinese labor camps and prisons and supplemented them with statements from former security officers and doctors with knowledge of China's transplant practices. Gutmann states in his book that organ procurement from political prisoners probably began in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region in the 1990s and then spread across China. Gutmann estimates that between 2000 and 2008, up to 64,000 Falun Gong prisoners were killed for their organs.

Kilgour-Matas-Gutmann investigation report

On June 22nd, David Kilgour, David Matas and Ethan Gutmann published the jointly prepared investigation report "Bloody Harvest / The Slaughter - An Update". The 680-page report provides forensic analysis from over 2,300 sources, including publicly available figures from Chinese hospitals, interviews with doctors claiming to have performed thousands of transplants; Media reports, public statements, medical journals and publicly available databases.

According to the investigation report, between 60,000 and 100,000 organ transplants have been performed annually at 712 liver and kidney transplant centers across China since 2000 to 2016, so that to date almost 1.5 million organ transplants have been performed without China having a functioning organ donation system.

The report finds that the number of organ transplants in China is far higher than the Chinese government said; the organ sources for this high number of organ transplants come from killed innocent Uyghurs, Tibetans, domestic Christians, and mainly Falun Gong practitioners; and organ harvesting is a crime in China involving the Communist Party, state institutions, the health system, hospitals and transplant doctors.

Involuntary organ harvesting allegations in Xinjiang

Ethan Gutmann, a journalist and China expert, concluded that conscience harvesting from prisoners in northwestern Xinjiang Province was widely targeted in security raids and "hard strikes" in the 1990s when members of the Uyghur ethnic group were targeted was common. In 1999, Gutmann said, organ harvesting began to decline rapidly in Xinjiang, while the overall rate of organ transplants rose across the country. In the same year, the Chinese government began the nationwide suppression and persecution of Falun Gong . Gutmann suspects that the new prison population of Falun Gong followers overtook the Uyghurs as the main source of organs. Concerns about involuntary organ harvesting were resurrected when China redoubled its efforts to stamp out extremism and separatism by interning a large portion of the Uyghur population in re-education camps in Xinjiang. There is supposed to be a significant market for the organs of Muslims. According to reports, Middle Eastern Muslim customers are demanding halal organs which must have come from another Muslim person.

Developments from 2006 to 2017

2006 to 2013

2006: In March 2006, the Chinese Ministry of Health issued provisional regulations on the clinical use of human organs for transplants. These set new requirements for medical institutes to be able to carry out transplants. The regulations said, among other things, that transplants should be limited to institutions that can prove the organ sources. The provinces of China are responsible for the planning of clinical application and transplant facilities are obliged to incorporate ethical, medical, surgical and intensive medical skills into the overall process of organ transplants. In April the “Commission for the Clinical Application of Technologies for Human Organ Transplantation” was established, which is responsible for coordinating and standardizing clinical practice. In November 2006, a national summit followed at which the regulators were presented.

Professor Guo Shuzong performed several experimental face transplants at Xijing Hospital, which eventually led to the world's first face transplant that included bones in April. The organ donor had been found to be brain dead prior to the transplant.

2007: In May 2007, a new ordinance from the Chinese Ministry of Health came into force, which was supposed to regulate the transplantation of human organs and to prohibit organ trafficking and organ removal without the written consent of the person concerned.

The aim of this regulation was to combat illegal transplants by punishing medical professionals involved in the commercial organ trafficking with fines and suspensions and only allowing selected hospitals to perform organ transplants. As a result of this systematic restructuring, the number of approved transplant facilities fell from over 600 in 2007 to 87 in October 2008. 77 hospitals received preliminary approval from the Ministry of Health.

In July 2007, in line with the Istanbul Declaration, the Ministry of Health issued a measure that Chinese citizens would be given priority as organ recipients to combat transplant tourism.

After years of discussion, in October 2007 the Chinese Medical Association promised the World Medical Association to end the practice of forcibly harvesting organs from sentenced inmates. Prisoners should only be allowed to donate their organs to their closest relatives. In order to be able to ensure implementation, safeguards should be established that include the documentation of the organ donor's written declaration of consent as well as a renewed review of all death sentences by the Supreme People's Court. In addition, specialists for organ transplants should not be called in until the organ donor has been officially declared dead.

The proposed regulations were approved by both the WHO and the transplant society, but Huang Jiefu stated at a transplant conference in Madrid in 2010 that over 100,000 transplants had been performed in China between 1997 and 2008, more than 90% of which were from executed inmates.

2008: In April 2008, at a symposium, legal and medical experts discussed the diagnostic aspects that should be considered when determining brain death in organ donors. In the same month, a registry of liver transplants was set up in Shanghai to monitor follow-up care. At the same time, a nationwide advertising campaign was initiated to attract organ donors. In the campaign, a proposal was made that voluntary organ donors can have their consent entered in their driving licenses.

2009: Despite these advertising campaigns, China Daily wrote a year and a half later that 65% of all transplanted organs were still from death row inmates, which Deputy Health Minister Huang Jiefu described as "not a good source for donated organs."

2010: The Chinese Ministry of Health, in cooperation with the Chinese Red Cross, established a posthumous organ donation system in March 2010. Huang Jiefu announced that a pilot project would first be tested within ten regions, including the cities of Tianjin, Wuhan and Shenzhen. This is intended to enable citizens to include their consent to organ donation in their driving license. At the same time, the family members of the organ donors would receive financial support. Through these measures, the Chinese authorities hoped that the need to use organs of sentenced inmates would be reduced and the sale of illegal organs on the black market would be curbed. The measure of attracting family members for organ donation by means of financial support is, however, not permitted according to WHO standards.

From 1977 to 2009 there were only 130 voluntary organ donations in China, but 120,000 organs were transplanted during the same period.

2012: In March 2012, Huang Jiefu, as deputy health minister, again admitted that the practice of organ harvesting from detainees was continuing in China, but that the intention was to end the practice within the next five years. Huang told China's Xinhua News Agency that "the promise to end the use of organs of sentenced inmates represents the government's decision." However, the Chinese Minister of Health did not want to confirm this statement.

In September, Damon Noto (DAFOH) submitted the report "Organ Harvesting from Religious and Political Dissidents by the Communist Party of China" to the Foreign Affairs Commission of the US Congress, which states, among other things, "Doctors outside of China have confirmed that their patients are traveled to China and obtained organs from Falun Gong practitioners there. "

2013: In May 2013, Huang argued in an interview with the Australian television broadcaster ABC TV that prisoners are allowed to donate organs, although this directly violates the international ethical standards of the World Medical Association as well as the transplant society.

At the National Transplant Congress of China on October 31, 2013, the "Hangzhou Declaration" was announced and presented to the public on November 2. In this declaration, the 38 participating hospitals committed themselves to "comply with ethical standards regarding the origin of organs and only allow voluntary organ donations". However, since not all transplant facilities had agreed to this declaration, a campaign was initiated to stop the practice of organ harvesting from prison inmates. The Chinese health minister promised in the same year that China would stop using organs from executed inmates from mid-2014.

2014 to 2016

2014: One year later, in March 2014, Huang, head of the Chinese Organ Donation Committee, announced that he would integrate prisoners' organs into the Chinese organ donation and distribution system and classify them as "voluntary organ donation" by Chinese citizens. This sparked outrage from leading international organ transplant experts, who called for an end to exchanges with Chinese experts.

In the spring of 2014, senior officials from the US and Australian International Transplant Society wrote an open letter to Chinese President Xi Jinping, complaining about the continued abuse within the Chinese transplant system.

In December 2014, Huang Jiefu published a press release in the Chinese media that as of January 2015, organs from executed prisoners will no longer be used without disclosing concrete measures for implementation. But back in January 2015, Huang told People's Daily that prisoners can still donate organs "voluntarily" because prisoners on death row are, after all, citizens. A year earlier, Huang told the Beijing Times: "Once the organs of willing execution candidates are fed into our general distribution system, they will be treated as a voluntary donation from citizens."

2015: Nevertheless, in August 2015, Huang invited representatives from the Transplant Society, the World Health Organization and the Istanbul Declaration to a large conference in Guangzhou.

Gosteli Hauser of Amnesty International told Der Zeit in October 2015 that, despite Huang's statements, organ harvesting from executed people in China was still not prohibited by law. According to the medical ethicist Norbert Paul and the pharmacologist Huige Li, Huang's statements do not sound like an end to organ removal from the executed.

In December 2015, leading medical and ethics experts commented on the situation in China in an article in BMC Medical Ethic and found that organs from prisoners are still being used for transplant purposes, which have simply been redesignated as "voluntary organ donation by citizens". This semantic trick is only used to colorize the use of organs by political prisoners sentenced to death.

Telephone inquiries at transplant centers in China revealed that many of these centers are still providing organs very quickly. A hospital in Guangzhou, Henan Province said, "they could even afford the luxury of only taking organs from living younger donors, under 40 years old." The hospital also pointed out that a liver is available within 3 to 5 days, sometimes within two weeks, and very rarely more than a month.

2016: On February 18, 2016, Huige Li, Professor of Vascular Pharmacology at Gutenberg University Mainz, confirmed his assumption, expressed a year earlier, that Huang's press release was just a deception and that the responsible state organs in China have not made any changes to the law to this day that prohibit the use of organs by prisoners and make it a criminal offense. On the website of the National Commission for Health and Family Planning (previously the Ministry of Health) neither regulations nor laws can be found that have to do with Huang's announcement.

On May 5, 2016, the website of the "China Organ Transplantation Development Foundation," according to the New York Times, is supposed to oversee the transition from "prisoner organ donation" to a new system that allows prisoners to still donate organs.

On August 18, 2016, the international congress of the Transplantation Society (TTS) took place in Hong Kong with Chinese representatives. Among them was liver surgeon Huang Jiefu, head of the Organ Donation and Organ Transplant Committee and former Deputy Minister of Health. Subsequently, the China-controlled media Global Times , Wen Wei Po and Ta Kung Pao announced that the Hong Kong convention had shown that China's transplant system had been internationally accepted. That statement was denied at a press conference the next day by the President of the Transplantation Society, Philip J. O'Connell, who pointed out that no one should interpret his words that way. On the contrary, the world community is "appalled by the practices that the Chinese have used in the past," said O'Connell. Jeremy Chapman, former president of the Transplantation Society, also denied the allegations, saying that a study presented at Congress suggested that ethical standards were violated. Should this suspicion prove true, China will be "publicly exposed and forever excluded from our congresses - this also applies to publications in the transplant journal".

2017

Conference on “International Organ Trade and Transplant Tourism” in the Vatican

From February 7th to 8th, a two-day conference on “International Organ Trade and Transplant Tourism” was held at the invitation of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences . With this meeting the Vatican wanted to advance the fight against international organ trafficking. Experts and representatives of the United Nations, non-governmental organizations and authorities as well as scientists from more than 20 countries were invited to discuss strategies for containing this phenomenon.

Martin Patzelt , member of the Human Rights Committee, welcomed the conference because it "opens up another chance that the government in China will no longer ignore illegal organ removal, but on the contrary, like all states that want to observe human rights, will decisively combat it". Patzelt demanded: “We should follow the example of Italy and also significantly tighten our legislation against organ trafficking. Here, we MEPs in the Committee for Human Rights and Humanitarian Aid in the German Bundestag are called upon. It is high time we, as human rights activists, still want to look in the mirror. "

Those invited included former Chinese Deputy Health Minister Huang Jiefu, now chairman of the Chinese National Organ Donation and Transplantation Committee, member of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, and deputy director of the mysterious Party Committee that cares for the health of senior officials, representing China , which has been suspected for over a decade of murdering masses of religious prisoners for high profit.

Huang's presence at the discussion in the Vatican was announced in advance in the People's Daily with the words that he would "share China's solution of organ donation and transplantation with the world - the Chinese way." But at the conference Huang only showed two slides showing the "Transplant reform" in China and the country's fight against illegal transplant activities. At the same time, he rejected any criticism, as the problem had already been eliminated in 2015; he also denied that prisoners of faith were murdered for their organs. However, critics doubt that China has kept its promise because of insufficient transparency in the health system, the lack of organ donors and the longstanding illegal organ trade.

Another member of the Chinese delegation, medical doctor Haibo Wang, said that with one million transplant centers, it is impossible to have "full control" of all organ transplants in China. However, this statement contrasts with the latest research report by Kilgour, Matas and Gutmann , which shows that between 60,000 and 100,000 kidney and liver transplants are performed annually in China in only 700 transplant centers that receive government support.

Protests in advance: That is why 11 international medical ethicists and human rights experts, including Wendy Rogers, Arthur Caplan, David Matas , David Kilgour and Enver Tohti, wrote a letter to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in advance, in which they asked the organizers of the conference “the Consider plight of prisoners in China who are treated as human organ banks ”. Organ harvesting investigators in China and human rights lawyers urged the Academy to dismiss Huang for his involvement in systematic organ harvesting from prisoners of conscience in China, and invite investigators to ensure a balanced discussion.

In response to the letter, Marcelo Sanchez Sorondo, Chancellor of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, warned that he “wanted to promote political agendas”. Wendy Rogers found this reaction "outrageous" and as an attempt to "avoid discussion by calling it political". Rogers added that "the weight of the evidence is such that China must verifiably state that it does not, and not the other way around".

Italian Senator Maurizio Romani, Vice President of the Health Commission, told Quotidianosanitá , “Without a free and independent investigation, there is no evidence that China has actually stopped the cruel organ harvesting, mainly from Falun Gong practitioners, but also from Christians and others political prisoners. ”A day later, Romani pointed out at a press conference that Huang Jiefu tried to cover up the organ harvesting taking place in China after numerous investigations had proven its existence. But Romani regarded the cover-up attempt as just as nonsensical as the claim that National Socialism did not exist.

Protests within the conference: The New York Times reported that during the conference there was also a confrontation with Huang Jiefu when he declared that "China is fixing its way" after he had already declared in 2014 that as of 2015 there will be no organs Captured.

Wendy Rogers, Chair of the Organ Harvesting Coalition Scientific Advisory Committee and medical ethics expert at Macquarie University, Australia, found Huang Jiefu's presence at the transplant conference "shocking".

Gabriel Danovitch of the University of California School of Medicine in Los Angeles asked Huang Jiefu directly if the regime was continuing to use organs from prisoners.

Jacob Lavee, President of Israel's Transplant Society, called for China to be accountable. The World Health Organization should "carry out unannounced examinations and interview relatives of donors". Lavee added, "Unless there is honesty and accountability for what is happening - the killing of innocents on command - there is no guarantee of ethical reform" in China.

Reactions: According to the New York Times, this conference coincides with the Pope's efforts to improve relations with and travel to China. But in December of last year, Hong Kong Cardinal Joseph Zen had already sharply opposed any rapprochement with the communist regime in China in an interview with Time Magazine : "Whoever does that betrays Christ," said Zen.

The Italian daily La Repubblica reported that China was trying to use the Vatican to cover up the crimes of forced organ harvesting.

The International Society for Human Rights (ISHR) criticized Huang Jiefu's participation with the allegation that it was partly responsible for the fact that “hundreds of thousands of organs from completely unclear sources” had been transplanted in China.

Ethan Gutmann , a China analyst and one of the lead investigators into organ harvesting from dissidents in China, pointed out that the Vatican was on its way to moving closer to China and that this could have ended in the complete moral decline of the Vatican. Gutmann also criticized Francis Delmonico, the former head of the Transplant Society (TTS), who was one of the main organizers of the congress. According to Gutmann, Delmonico is working hand-in-hand with Huang to promote the idea that China would make medical reforms rather than pointing out what had really happened so far. Delmonico and Huang want to "burn the story, burn the corpses so that they are never seen again," said Gutmann. In an email to the Guardian , Delmonico wrote that Huang's "relentless drive to bring about change in China resulted in the ban on the use of organs from executed prisoners in January 2015". However, last year (2016), Delmonico testified under oath before the United States Congressional Committee that the practice had not actually been abandoned in China.

Torsten Trey of DAFOH said, "You cannot refute decades of organ harvesting from hundreds of thousands of Falun Gong practitioners and other prisoners of conscience with two slides." Trey pointed out that Wang's justification that the government cannot control all transplant activities, even them International concerns heightened because "China cannot guarantee that the organ harvesting has stopped" and stressed the need for a thorough, independent international investigation. In addition, Trey advised the Vatican not to be fooled by China's whitewashing agenda, but to ask an essential question, namely, "How many Falun Gong practitioners, Uyghurs, Tibetans, and Christians loyal to the Vatican have become their organs in the past few decades deprived? ”China's lack of transparency is a mask behind which it hides its sins.

Lord David Alton , human rights attorney and prominent Catholic, said he was "deeply alarmed" by the constant reports of "barbaric" organ harvesting in China. Alton had asked the Pontifical Academy to also invite the investigators who had found out that the organ harvesting has a much larger dimension than previously assumed. According to Alton, it is right to deal with China on this issue, but "it is vital that we do this critically and transparently, and not in a way that provides China with a propaganda victory".

Press release of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences: After the conference on “International Organ Trade and Transplant Tourism”, the participants issued a statement calling, among other things, for the “use of organs from executed prisoners and payments to donors or to the closest relatives of deceased donors ... to be condemned worldwide and to be prosecuted nationally and internationally ”. DAFOH issued a press release on this, referring to the fact that "the current organ donation system in China is largely based on enticing payments to families whose relatives have died". Poor families are "very susceptible to accepting money for the organs of deceased relatives, especially when they are faced with high hospital costs". This is another ongoing ethical failure of China's transplant system, according to DAFOH.

China increases the number of approved transplant centers

At a conference in Beijing on May 7, Huang Jiefu, head of the Organ Donation and Organ Transplantation Committee, announced that China will add 300 organ transplant hospitals to the 173 hospitals that have been licensed to perform organ transplants over the next five years. Furthermore, Huang insisted that China carried out nearly 10,000 organ transplants in 2016. According to the investigation report by David Kilgour, David Matas and Ethan Gutmann from June 2016, however, organ transplants were carried out in China in 865 hospitals between 2000 and 2016, of which only 165 were officially recognized. During this period, between 60,000 and 100,000 kidney and liver transplants were performed annually in 712 hospitals (approximately 1.5 million). The National Organ Transplant Register in Wuhan listed 34,832 kidney transplants nationwide in 2000 alone.

Transplant conference in Kunming

A transplant conference was held in Kunming on August 5th and international health officials were invited by Huang Jiefu, director of the National Organ Donation and Organ Transplant Committee. According to the Global Times , the party's own newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party, they are said to have applauded the transplant reforms introduced by Huang Jiefu.

According to the magazine KATHOLISCHES , the political advisor to the Pope Curia Bishop Marcelo Sanchez Sorondo took part in the conference, who is said to be known for his international “left-liberal to left-wing radical” contacts. In a public statement, Sorondo stressed “the Pope's love for China”. His presence was considered a return visit after Huang Jiefu attended the “International Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism” conference at the Vatican in February 2017. According to GlobalTimes , Sorondo reportedly said, "China could be a model we need today to respond to globalization, a model for human dignity and freedom, a model for the destruction of the new type of organ slave trade."

Another participant was Campbell Fraser, an organ trafficking expert at Griffith University in Australia. According to the Global Times , Fraser said the model developed in China "is an example for other countries and provides the foundation for an ethical practice against organ trafficking." Although all of the allegations regarding organ harvesting from living Falun Gong practitioners in the People's Republic of China come from Western investigators , none of whom are believed to practice Falun Gong, such as Kirk Allison, Edward McMillan-Scott , David Kilgour , David Matas , Ethan Gutmann, and others Fraser told The Star , a Malaysian daily newspaper owned by the Malaysian Chinese Association , that "for purely political purposes, Falun Gong fabricates stories of organ harvesting from its adherents."

Another participant in the transplant conference was Francis Delmonico, who confirmed Huang Jiefu's plan that China would be number one in the world for organ transplants from 2020 and will replace the USA with the words: “This switch is very real, very real and very well-versed . These are not rumors and the support of the government is very real. "Delmonica was already criticized in February at the conference on" International Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism "in the Vatican by Ethan Gutmann for collaborating with Huang Jiefu to promote China's plans internationally. instead of pointing out the real events that are happening in China. According to Gutmann, Delmonico and Huang want to "burn the story together, burn the corpses so that they are never seen again". Although Delmonico consistently cites China's ethical behavior and claims that China has not used prisoners as organ suppliers since 2015, he testified under oath before the United States Congressional Committee in 2016 that China has still not given up the practice.

Philip O'Connell, the former president of the transplant society, also reportedly said that Falun Gong's allegations were baseless, according to The Star . However, Philip O'Connel had already told the New York Times in Hong Kong in 2016 at a press conference that the practice of removing organs from executed prisoners had been a shock for the entire world. O'Connell pointed out, “Nobody can interpret the words I have addressed to China's representatives in such a way that the transplant society accepts the [Chinese] system. You may say it, but this is not the truth. "

Doctors from around the world strongly criticized the health organization representatives for welcoming the transplant reform claims without adequate research into the forced organ harvesting of prisoners of conscience. Conference organizer and keynote speaker Huang Jiefu once again acted as if he did not know anything about the organ harvesting, even though he himself admitted in 2005 that it existed. Recent announcements of a "special economic zone" on Hainan Island sparked further concerns about the imminent expansion of transplant tourism to China. Torsten Trey, Director of DAFOH asked: “Can one of the organizers guarantee that no organs from prisoners of conscience are channeled into the public organ donation system? If not, any recognition is premature. "

According to Trey, unsubstantiated claims should not be countered with blind faith, otherwise “the so-called 'Chinese dream' in China's transplant centers would turn into a nightmare” for an indefinite number of prisoners of conscience. Because although China claimed that organs would no longer be used from executed prisoners as of 2015, the 1984 law that allowed the practice has not been repealed to this day. "It is inconceivable," says Trey, "that renowned health organizations limit their attention to alleged reforms, while the fate and organ procurement of prisoners of conscience remains unmentioned, unchecked and unsolved."

2019

Data falsification allegations: Although Chinese authorities announced back in 2010 that the country would move away from using prisoners as an organ source and rely entirely on voluntary donation, and reaffirmed in 2015 that voluntary donors are the only source of organ transplants in China, critics point for evidence of systematic falsification of data related to voluntary organ donation, which calls into question China's reform claims.

In November 2019, BMC Medical Ethics reported an analysis of data on voluntary organ transplants from 2010 to 2018. The data sets came from two national sources, several sub-jurisdictions, and individual Chinese hospitals. The researchers found compelling evidence of "human-controlled data creation and manipulation" in the national datasets, as well as "inconsistent, implausible or anomalous data artifacts" in the provincial datasets, suggesting that the data "may have been tampered with for compliance enforce central quotas ". Among other things, it was found that the alleged growth rate of voluntary donations "corresponds almost exactly to a mathematical formula" and was derived from a simple quadratic equation with almost perfect model parsimony. These results appear to undermine official claims about the level of voluntary organ donation in China. The investigation came to the conclusion that a large number of facts can only be plausibly explained by "systematic falsification and manipulation of official organ transplant data sets in China". The investigators also stated that "some apparently non-voluntary donors are wrongly classified as voluntary". This happens in addition to real voluntary organ transplant activity, which is often promoted by high cash payments, which is not allowed according to WHO standards.

In a response published by the state-run Global Times news agency , Chinese health officials countered that each nation's organ transplant dates could be modeled on. Wang Haibo, head of the China Organ Transplant Response System, which is responsible for organ allocation, defended the accuracy of the Chinese transplant data by saying that "the data from all countries could fit into one equation."

However, the authors of the BMC report suggest that China's model parsimony is one to two orders of magnitude smoother than that of any other nation, even those that have seen rapid growth in organ transplantation.

Waiting times

China has by far the shortest waiting times for organ transplants, and research assumes that prisoners for using their organs on demand are executed as soon as an organ recipient needs them. Transplant tourists reported that they received a donor kidney in China within a few days of arriving. In one case, a patient reported that he had four kidney transplants for US $ 20,000 in one week at Shanghai First People's Hospital in 2003, but they were all rejected. Two months later, he traveled to China again and received four more kidney transplants until the eighth kidney was tolerated by blood and tissue. The Kilgour-Matas investigation report quotes China's International Transplant Support Center, which stated on its website that it would normally only take a week to find a suitable organ (kidney) donor, a month at most. It is possible for international patients to plan their operations in China in advance, which is not possible in systems that rely on voluntary organ donation.

Comparing organ transplant waiting times in China, the average organ transplant waiting times in Australia are between 6 months and 4 years, and in the UK between 3 and 5 years, in the United States the waiting time averages 4.5 years (kidney) and in Canada 6 years. For kidneys, waiting times are between 4 and 8 years in Germany and between 2 and 6 years in Austria.

Bibliography

- David N. Weisstub, Guillermo Díaz Pintos: Autonomy and Human Rights in Health Care: An International Perspective. Springer, Dordrecht 2008, ISBN 1-4020-5840-3 .

- Ethan Gutmann: The Slaughter: Mass Killings, Organ Harvesting, and China's Secret Solution to Its Dissident Problem. Prometheus Books, 2014, ISBN 978-1616149406 .

- Steven J. Jensen: The Ethics of Organ Transplantation. The Catholic University of America Press, Washington 2011, ISBN 978-0-8132-1874-8 .

- Walter Land, John B. Dossetor: Organ Replacement Therapy - Ethics, Justice and Commerce. Springer, New York 1991, ISBN 3-540-53687-6 .

Web links

- DAFOH (Doctors Against Organ Harvesting )

- Investigation Report into Allegations of Organ Harvesting from Falun Gong Practitioners in China , 2007, David Kilgour, David Matas

- Organ Harvesting in China - Between Life and Death on YouTube , 2011, accessed on May 22, 2020 (TV report from the NTDTV documentary series “Zooming In”, 52 minutes).

- Killed for Organs: China's Secret State Transplant Business, NTDTV, 2012, 8 minutes on YouTube

- Human Harvest: China's Organ Trafficking , Dateline from SBS One TV, April 7, 2015, incl.transcript

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jiefu Huang, Yilei Mao, J. Michael Millis: Government policy and organ transplantation in China . In: The Lancet . tape 372 , no. 1937 , December 2008, p. 1937–1938 , doi : 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (08) 61359-8 (English).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Health system reform in China . In: The Lancet . tape 372 , no. 9648 , October 2008, p. 1437 , doi : 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (08) 61601-3 (English).

- ↑ a b c Military hospital in China conducts world-first face transplants , The Daily Telegraph (London), November 28, 2008, accessed February 3, 2016

- ↑ a b c Annika Tibell, The Transplantation Society's Policy on Interactions With China , Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting, May 8th 2007, accessed on February 3, 2016

- ↑ Craig S. Smith, Doctor Says He Took Transplant Organs From Executed Chinese Prisoners , New York Times, June 29, 2001, accessed February 3, 2016

- ↑ a b c d e f g David Kilgour, David Matas: "Bloody Harvest - Investigation Report on Allegations of Organ Harvesting from Falun Gong Practitioners in China" (revised and expanded version, November 2007), organharvestinvestigation.net, accessed March 3, 2007. February 2016

- ↑ Ethan Gutmann: China's Gruesome Organ Harvest - The whole world isn't watching. In: ethan-gutmann.com. November 24, 2008, accessed September 24, 2019 .

- ↑ Ethan Gutmann, “The Slaughter: Mass Killings, Organ Harvesting, and China's Secret Solution to Its Dissident Problem.”, August 2014, Prometheus Books, ISBN 978-1616149406 ; German edition: GoodSpirit Verlag

- ↑ Larry Getlen, "China's long history of harvesting organs from living political foes," New York Post, August 9, 2014, accessed February 3, 2016

- ↑ Ruth Ingram: Organ harvesting trial continued in 2019 | Bitter winter. In: Bitter Winter (German). April 14, 2019, accessed on October 2, 2019 (German).

- ↑ a b c d Jane Macartney, "China to 'tidy up' trade in executed prisoners' organs" , The Times, December 3, 2005, web archive, accessed June 16, 2017

- ↑ a b c "New system to boost number of organ donors" , China Daily, accessed February 4, 2016

- ↑ a b Press release, "Chinese Medical Association Reaches Agreement With World Medical Association Against Transplantation Of Prisioners's Organs," Medical News Today, October 7, 2007, accessed February 4, 2016

- ^ "Shanghai" , shanghai.gov.cn, June 16, 2008, accessed on February 4, 2016

- ↑ a b c "China admits death row organ use," BBC News, August 26, 2009, accessed February 5, 2016

- ^ Robertson, Matthew, "China Transplant Official Backtracks on Prisoner Organs," The Epoch Times, March 12, 2014, accessed February 5, 2016

- ^ "China media: Military spending" , BBC, March 5, 2014, accessed February 5, 2016

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Martina Keller : "Where do China's kidneys come from?", Die Zeit, October 29, 2015, issue 44

- ↑ a b "HUMAN ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION" - A Report on Developments Under the Auspices of WHO (1987–1991) , page 7, WHO, Geneva, 1991, accessed on February 9, 2016

- ^ A b c "The Bellagio Task Force Report on Transplantation, Bodily Integrity, and the International Traffic in Organs" . icrc.org, accessed February 9, 2016

- ^ Tom Treasure, "The Falun Gong, organ transplantation, the holocaust and ourselves," Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine (Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting) 100: 119–121, accessed February 9, 2016

- ↑ David N. Weisstub, Guillermo Díaz Pintos, “Autonomy and Human Rights in Health Care: An International Perspective” , Springer, 2007, p. 238, ISBN 1-4020-5840-3 , accessed February 9, 2016

- ↑ a b "China fury at organ snatching 'lies'" , BBC News, June 28, 2001, accessed February 9, 2016

- ^ KC Reddy: Walter Land , John B. Dossetor: "Organ Replacement Therapy: Ethics, Justice, Commerce" , New York, Springer-Verlag, 1991; p 173, ISBN 3-540-53687-6 , accessed February 9, 2016

- ^ Clifford Coonan, David McNeill, Japan's rich buy organs from executed Chinese prisoners , The Independent (London), March 21, 2006, accessed February 9, 2016

- ↑ Lu Daopei, “Blood and marrow transplantation in mainland China (Supplement 3)” , Hongkong Medical Journal, June 3, 2009) 15 (Suppl 3): 9-12, accessed February 16, 2016

- ↑ XH Wang, F. Zhang, XC Li, JM Qian, LB Kong, J. Huang, et al. "Clinical report on 12 cases of Living donor partial liver transplantation", National Medical Journal of China, 2002; 82: 435-439

- ↑ "Early experiences on living donor liver transplantation in China: multicenter report" ( Memento of the original from July 18, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Chinese Medical Journal

- ↑ Fu-Gui Li, Lu-Nan Yan, Yong Zeng, Jia-Yin Yang, Qi-Yuan Lin, Xiao-Zhong Jiang, Bin Liu, “Donor safety in adult living donor liver transplantation using the right lobe: Single center experience in China, ” wjgnet.com, accessed February 17, 2016

- ↑ WH Wu, YL Wan, L. Lee, YM Yang, YT Huang, CL Chen, et al., "First two cases of living related liver transplantation with complicated anatomy of blood vessels in Beijing", World Journal of Gastroenterol (2004) ; 10: 2854-2858

- ↑ a b Peter Woodford, "Whole ovary transplant reverses early menopause" ( Memento of the original from July 14, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , National Review of Medicine vol 4 no.5, March 15, 2007, accessed February 17, 2016

- ↑ Zhonghua, Klaus Chen, "Current Situation of Organ Donation and Transplantation in China" of the Institute of Organ Transplantation, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College and Huazhong University of Science and Technology, PRC, pub: City University of Hong Kong

- ↑ "China's first human face transplant successful," Xinhua News Agency, April 15, 2006, accessed February 19, 2016

- ^ "'First face transplant' for China ", BBC News, April 14, 2006, accessed February 19, 2016

- ↑ Ian Sample, “Man rejects first penis transplant,” The Guardian (London), September 18, 2006, accessed February 19, 2016

- ↑ Weilie Hu, Jun Lu, et.al., “A preliminary report of penile transplantation,” European Urology Journal, vol. 50, October 4, 2006, pp. 851-853, accessed February 19, 2016

- ↑ Jean-Michel Dubernard, J. Lu, et.al., “Penile transplantation?” , European Urology Journal, vol. 50, October 4, 2006, pp. 664–665, accessed February 19, 2016

- ^ A b H. Hillman: Harvesting organs from recently executed prisoners. Practice must be stopped. In: BMJ (Clinical research ed.). Volume 323, number 7323, November 2001, p. 1254, PMID 11758525 , PMC 1121712 (free full text).

- ↑ Press release, "World Medical Association demands China stops using prisoners for organ transplants" ( Memento from April 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), World Medical Association, May 22, 2006, accessed on March 21, 2016

- ^ "Human organ and tissue transplantation" , WHO, accessed on February 19, 2016

- ↑ "Draft guiding principles on human organ transplantation" , World Health Organization, accessed on February 19, 2016

- ↑ "Illegal Human Organ Trade from Executed Prisoners in China" ( Memento of the original from June 10, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , www1.american.edu, accessed February 19, 2016

- ↑ "China, illegal trade in human body parts: hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, One Hundred Fourth Congress, first session, May 4, 1995" , worldcat.org, accessed on February 19, 2016

- ↑ "Senate Committee Hears How Executed Prisoners' Organs are Sold for Profit" ( Memento of the original from April 29, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Laogai Report, November 1995. Laogai Research Foundation, accessed February 19, 2016

- ↑ a b Calum MacLeod, "China makes ultimate punishment mobile," USA Today, May 15, 2006, accessed February 19, 2016

- ↑ a b c d Steven Mufson, "Chinese Doctor Tells of Organ Removals After Executions" ( September 21, 2008 memento on WebCite ), The Washington Post, June 27, 2001, archived from the original on September 21, 2008, accessed September 19 , 2001 February 2016

- ↑ CTVNews.ca Staff, Report alleges China killing thousands to harvest organs , CTVNews, June 23, 2016, accessed September 9, 2016

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Huige Li, Interview on “Dislodged - Organs on Order” , 3sat, February 18, 2016, ZDF-Mediathek ( Memento of the original from March 16, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: Der Archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed April 13, 2016

- ↑ Huang Jiefu et al., China: Health System Reform , The Lancet, October 20, 2008, accessed February 14, 2017

- ^ Zhang Feng, New rules to regulate organ transplants , China Daily, May 5, 2006, accessed February 14, 2017

- ↑ Shan Juan, Health authorities to define legal brain death , China Daily, August 23, 2007, accessed May 26, 2017

- ↑ Wendy A. Rogers, Matthew P. Robertson, Jacob Lavee, Engaging with China on organ transplantation , The BMJ, February 7, 2017, accessed June 1, 2017

- ^ David Kilgour, Blood Harvest / The Slaughter - An Update (PDF), End Organ Pillaging, page 286, accessed June 1, 2017

- ↑ Thomas Lum, Congressional Research Report # RL33437 , Congressional Research Service, August 11, 2006, web archive , accessed June 16, 2017

- ↑ a b Huige Li, “What's behind China's new announcement” , Ärzte Zeitung online, February 9, 2015, accessed on March 4, 2016

- ↑ "World Medical Association Council Resolution on Organ Donation in China" , World Medical Association, May 2006, web archive, accessed on June 16, 2017

- ↑ Price List for Organs of the China International Transplantation Network Assistance Center ( Memento of October 29, 2005 in the Internet Archive ), Shenyang, January 15, 2016, accessed April 22, 2006

- ↑ Guarantee for organ transplants from the China International Transplantation Network Assistance Center ( Memento from May 9, 2006 in the Internet Archive ), Shenyang, April 22, 2006, accessed on July 29, 2017,

- ^ A b "Organ sales 'thriving' in China," BBC News, Sept. 27, 2006, "Organ selling in China. BBC investigates undercover, ” accessed March 4, 2016

- ^ A b David McNeill, Clifford Coonan, "Japanese flock to China for organ transplants," Asia Times Online, April 4, 2006, accessed April 19, 2016

- ^ A b Andrea Gerlin, “China's Grim Harvest” , Time, accessed on March 21, 2016

- ^ Edward McMillan-Scott, "Secret atrocities of Chinese regime" Yorkshire Post, June 13, 2006, accessed March 21, 2016

- ↑ Falun Gong organ claim supported . In: theage.com.au . July 8, 2006, accessed October 4, 2019.

- ↑ Kirstin Endemann, "Ottawa urged to stop Canadians traveling to China for transplants," CanWest News Service, Ottawa Citizen, July 6, 2006, accessed March 23, 2016

- ↑ Calgary Herald, “Rights concerns bedevil China — Doing trade with regime must be balanced with values,” July 5, 2006, accessed March 23, 2016

- ↑ David Kilgour, David Matas, "Bloody Harvest, The killing of Falun Gong for their organs," seraphimeditions.com, p. 232, accessed March 23, 2016

- ^ The Washington Times, “Chinese accused of vast trade in organs,” April 27, 2010, accessed March 23, 2016

- ↑ Harry Wu, “Harry Wu questions Falun Gong's claims about organ transplants,” AsiaNews.it, August 9, 2006, accessed March 23, 2016

- ^ "Harry Wu mette in dubbio le accuse del Falun Gong sui trapianti di organi" ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , AsiaNews.it, August 9, 2006, accessed March 23, 2016

- ↑ Matas / Kilgour, "Appendix 16. Sujiatun" , organharvestinvestigation.net, accessed on March 24, 2016

- ↑ "Hospitals ban Chinese surgeon training" , The Sydney Morning Herald , December 5th 2006, accessed on 24 March 2016

- ↑ Reply of the Chinese Embassy in Canada to "China's organ harvesting report" , ca.china-embassy.org, July 6, 2006, accessed March 24, 2016

- ↑ Reply of the Chinese Embassy in Canada to "China's organ harvesting report" , ca.china-embassy.org, April 15, 2007, accessed on March 24, 2016

- ↑ a b "United Nations Human Rights Special Rapporteurs Reiterate Findings on China's Organ Harvesting from Falun Gong Practitioners" ( Memento of May 21, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), Information Daily, May 9, 2008, accessed on March 24, 2016

- ↑ a b Reports of the United Nations on "Organ Harvesting from Falun Gong Practitioners" , abstract as PDF accessed on March 24, 2016

- ↑ Manfred Nowak, UN Annual Report 2006 at the 4th session of the UN Human Rights Council , March 20, 2007, accessed on March 28, 2007

- ↑ a b Damon Noto, Gabriel Danovitch, Charles Lee, Ethan Gutmann, "Organ Harvesting of Religious and Political Dissidents by the Chinese Communist Party, House Committee on Foreign Affairs" ( Memento of the original from December 5, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , September 12, 2012, accessed March 25, 2016

- ↑ a b Matthew Robertson, "US Congress Hones in on Vast Organ Harvest in China" , Epoch Times, Sept. 12, 2012, accessed on 25 March 2016

- ^ "State Organs: Introduction" , seraphimeditions.com, accessed on March 25, 2016

- ↑ Rebeca Kuropatwa, "Matas New book Reveals transplant abuse" ( Memento of 24 September 2012 at the Internet Archive ), Jewish Tribune, September 19, 2012 Retrieved on March 25, 2016

- ↑ Mark Colvin, “Parliament to Hear Evidence of Transplant Abuse in China,” Australian Broadcasting Corporation, November 27, 2012, accessed March 25, 2016

- ↑ David Matas, Torsten Trey “State Organs, Transplant Abuse in China” , 2012, seraphimeditions.com, p. 144, accessed on March 25, 2016

- ↑ a b Larry getLen, "China's long history of harvesting organs from living political foes" , New York Post, August 9, 2014. Retrieved on March 25, 2016

- ↑ Jay Nordlinger, "Face The Slaughter: The Slaughter: Mass Killings, Organ Harvesting, and China's Secret Solution to Its Dissident Problem, by Ethan Gutmann," National Review, accessed March 25, 2016

- ↑ Barbara Turnbull, http://www.nationalreview.com/sites/default/files/nordlinger_gutmann08-25-14.html , The Toronto Star, October 21, 2014, accessed March 25, 2016

- ^ A b Ethan Gutmann: The Slaughter: Mass Killings, Organ Harvesting, and China's Secret Solution to Its Dissident Problem, Prometheus Books, p. 368, ISBN 978-1616149406

- ^ A b David Kilgour, Blood Harvest / The Slaughter - An Update (PDF) , End Organ Pillaging, p. 428, accessed August 26, 2016

- ↑ a b Mark Casper, China continues to harvest organs of prisoners: report , JURIST, June 24, 2016, accessed on September 5, 2016.

- ↑ Nathan Vanderklippe, Report alleges China killing thousands to harvest organs , The Globe and Mail, June 22, 2016, accessed September 9, 2016

- ↑ Terry Glavin, Glavin: China's harvest of human organs tells us what we need to know about human rights , Ottawa Citizen, June 22, 2016, accessed September 9, 2016

- ↑ a b Gabriel Samuels, China kills millions of innocent meditators for their organs, report finds , The Independent, June 29, 2016, accessed May 10, 2017.

- ↑ a b Megan Palin, 'A bloody harvest': Thousands of people slaughtered for their organs, new report reveals , News.com, June 28, 2016, accessed May 10, 2017.

- ↑ a b CNN WIRE, Report: China still harvesting organs from prisoners at a massive scale , FOX8, June 26, 2016, accessed May 10, 2017.

- ↑ Ethan Gutmann, Congressional Testimony: Organ Harvesting of Religious and Political Dissidents by the Chinese Communist Party , House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations; September 12, 2012, (web archive), accessed January 23, 2020

- ↑ Ethan Gutmann, The Xinjiang Procedure, ” Washington Examiner, December 5, 2011, accessed January 23, 2020

- ↑ David Brooks, The Sidney Awards Part II , New York Times, December 22, 2011, accessed January 23, 2020

- ↑ Martin Will, China is harvesting thousands of human organs from its Uighur Muslim minority, UN human-rights body hears , Business Insider, September 25, 2019, accessed January 23, 2020

- ↑ Emma Batha, UN urged to investigate organ harvesting , Reuters, September 24, 2019, accessed January 23, 2020

- ↑ Keoni Everington [Saudis allegedly buy 'Halal organs' from 'slaughtered' Xinjiang Muslims], Taiwan News, January 22, 2020, accessed January 23, 2020

- ^ "World's second face transplant performed in China" , New Scientist, accessed on March 28, 2007

- ^ "Chinese Man Gets World's Second Face Transplant" ( Memento September 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive ), health.dailynewscentral.com, April 15, 2006, accessed March 28, 2007