Pakakali

| Pakakali | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

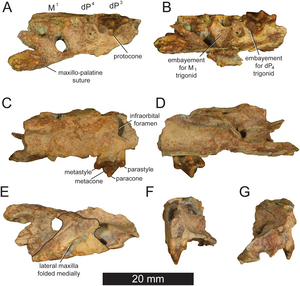

Upper jaw fragment from Pakakali (holotype) in different views |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Upper Oligocene ( Chattian ) | ||||||||||||

| 26 to 25 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

|

East Africa (Tanzania) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Pakakali | ||||||||||||

| Borths & Stevens , 2017 | ||||||||||||

Pakakali is a genus of the order Hyaenodonta , extinct carnivorous mammals that may beclose to predators . So far, only a remnant of the upper jaw has been found, which comes from eastern Africa and dates to the Upper Oligocene around 25 million years ago. The find refers to a rather small animal that was not yet fully grown, but probably lived as a carnivore and omnivore in a wooded, humid landscape. The evidence of Pakakali is the first from this period in Africa. It falls into a phase when the first representatives of the carnivores reached the continent. The genus was scientifically introduced in 2017.

description

Pakakali is one of the smaller representatives of the hyaenodonts. So far, the genus could only be covered with parts of the palate via an upper jaw bone . The find contains only one tooth, which is interpreted as the third premolar of the deciduous dentition . Two subsequent alveoli correspond to either the fourth deciduous or the fourth permanent premolar and the first molar . Based on the size of the find, a reconstructed body weight of 5.8 to 10.1 kg is likely, which is roughly comparable to a modern bobcat or a fossa . The development of the milk premolars and the presence of a permanent molar indicate that the individual was not yet fully grown. An infraorbital foramen was formed in the upper jaw above the third milk premolar. The palatine process extended between the posterior part of the third milk premolar and that of the first molar. The upper jaw itself has only been preserved in fragments and is partially deformed by sediment .

The only documented tooth of the permanent dentition is represented by the alveolus of the first molar. The actual tooth was estimated to be around 8.3 mm long. The only tooth actually preserved is the third milk premolar. The individual milk premolars in the hyaenodonts and today's predators resembled in a certain way the subsequent tooth in their permanent dentition, so that in Pakakali the third milk premolar with the fourth permanent premolar more or less matches. Its size was 7.0 mm in length and 4.2 mm in width. It had three pointed cusps on the chewing surface, the metaconus and the paraconus on the cheek side and the protoconus on the tongue side. The entire cheek-side part of the tooth was laterally pressed, so that the individual elevations were given a blade-like structure. The tooth was dominated by the paraconus, which towered the highest. However, it was not as uniformly triangular in shape as the related Masrasector . but inclined slightly backwards, the front edge (Preparacrista) rose at an angle of 45 °. The metaconus was pressed closely to the paraconus and was significantly lower than it, but not as conspicuous as the corresponding milk tooth from Masrasector . Between the sloping flank of the metaconus (postmetacrista) and the subsequent cutting ridge of the metastyle, a low cusp, there was a prominent bay-like depression. This structure indicates that the tooth was included in the crushing shears . The metastyle itself was around 2 mm long and thus made up around 30% of the entire tooth length. In relation, it exceeded the corresponding formation in Dissopsalis , which also lacked the striking bay. The front shear edge of the tooth, the parastyle, still reached 20% of the total tooth length in Pakakali . The protoconus formed the tongue-side part of the tooth and was comparatively low.

Fossil finds

The only fossil remains of Pakakali so far have been discovered in the Rukwa Basin in southwestern Tanzania in East Africa . The Rukwa Basin is part of the East African Rift and has one of the most powerful deposits in the region. The oldest still belong to the Permian . These are overlaid by sandstone-rich formations, the so-called Red Sandstone Group , which belong to two different stratigraphic units. The lower section is the Galula Formation , which is more than 500 m thick and belongs to the Cretaceous period . The abundant finds can be assigned to different dinosaurs and primeval mammals , and turtles and fish are also found. The 300 m thick Nsungwe Formation lies on top . It is in turn divided into two layers, the lower Utengule member and the upper Songwe member . The latter in particular is extremely rich in fossils. It consists of a series of coarse and fine clastic sandstones with embedded layers of clay / silt stones . The deposits go back to a ramified river system that likely drained into a nearby marshland or wetland. Various layers of volcanic ash from an originally not far away eruption center are also switched on. An ash layer near the upper end of the Songwe Member was dated with the help of zircon measurements to an age of about 25.2 million years, which corresponds to the Upper Oligocene . In Songwe Member different Fund localities are known, one of which is Nsungwe 2 is that hid most extensive fossil material, including the discovery of Pakakali . The entire Fossilsprektrum the Songwe Members is further comprised of early primates , porcupine relatives , elephant-shrews and hyraxes , as well as of crocodiles , frogs , fish, crabs and countless cases of aquatic molluscs . The Rukwa region thus belongs to a series of Upper Oligocene sites that line up like a string of pearls along the African rift valley. It begins in the north at Chilga in Ethiopia and continues south over the Eragaleit beds and the Lokone Hills in Kenya and other sites such as Nakwai to the Rukwa Basin in Tanzania. This offers a unique look into the paleogenic past of Africa.

Paleobiology

The tooth structure of Pakakali could speak for a preferred carnivorous to omnivorous way of life. The size of the animal is well below the threshold at which today's predators kill prey of their own body weight or heavier (the limit is around 21.5 kg). In relation to this, Pakakali probably ate animals with half or less of their own body weight. Using the geological and palaeontological data, a wetland landscape interspersed with forests is being reconstructed for the late Oligocene Rukwa Basin. As there is hardly any evidence of fossil relocation, Pakakali can be considered part of this biotope . It can be assumed that the genus assumed a position comparable to today's gray fox or the North American cat fret and killed small vertebrates in different types of landscape.

Systematics

|

Internal systematics of the Teratodontinae according to Solé & Mennecart 2019

|

Pakakali is a genus from the extinct subfamily of the Teratodontinae within the also extinct order of the Hyaenodonta . For a long time , the Hyaenodonta were considered members of the Creodonta , some of which are sometimes misleadingly referred to as "primal predators". The Creodonta in turn were regarded as the sister group of today's carnivores within the parent group of the Ferae . In the following years, however, the Creodonta turned out to be a non-self-contained group. They were then split into the hyaenodonta and the oxyaenodonta . The position of the pruning shears is characteristic of both groups , as it was shifted further back in the teeth compared to the predators. In the hyaenodonts, this often included the second upper and third lower molars. The earliest evidence of the hyaenodonts falls in the Middle Paleocene around 60 million years ago, they then disappeared again in the Middle Miocene around 9 to 10 million years ago. The Teratodontinae form within the Hyaenodonta the sister group of the family Hyainailouridae , both together are in the parent group of the Hyainailouroidea . The teratodontinae are characterized by the structure of the maxillary molars, in which the para- and metaconus are fused at the base, the latter usually overhanging the former. In contrast, in the Hyainailouridae the Para- and Metaconus are united to the Amphiconus and the Paraconus is higher than the Metaconus. With regard to the height of the two cusps, the Teratodontinae and the Hyaenodontidae show similarities , but in the latter, the para and metaconus also form an amphiconus. From a phylogenetic point of view, Pakakali is possibly one of the more basic representatives of the Teratodontinae with closer ties to genera such as Brychotherium or possibly Glibzegdouia . However, these appear largely as early as the Eocene . More fossil material from Pakakali is needed to substantiate the exact phylogenetic position .

The genus Pakakali was discovered in 2017 by Matthew R. Borths and Nancy J. Stevens using the only find so far, a fragmented upper jaw (specimen number: RRBP 09088) of a non-adult individual from the Nsungwe Formation in the Rukwa Basin in southwestern Tanzania scientifically first described . The generic name is made up of the Swahili words paka for "cat" and kali for "wild" or "impetuous". Together with the genus, the authors established the species P. rukwaensis . The specific epithet refers to the find region.

The discovery of the Pakakali find is the first of a hyaenodont from the Upper Oligocene in the Afro-Arab region. In the Eocene and Lower Oligocene, the hyaenodonts were very varied in the region, which is shown above all by the finds from the Fayyum in Egypt . The subsequent gap in tradition falls at a time when the predators first set foot on African soil. This was made possible by the closure of the Tethys Ocean and the creation of the land bridge to the Eurasian region. One of the oldest recorded predators in Africa is the Mioprionodon from Eastern Africa, which represents a relatively small predator without a highly specialized set of teeth. Both the predators and the hyaenodonts occupied the same ecological niches . To date, too few finds are known to reconstruct the predator community of this time and to precisely understand the gradual displacement of the hyaenodonts by the predators. What is striking, however, with the hyaenodonts is a development towards strongly hypercarnivorous specialists (with a meat content of more than 70% in today's predators), as well as an expansion of the food spectrum, for example through a durophage (based on hard-shelled molluscs ) diet. This is partly connected with the formation of extremely small and extremely large shapes.

literature

- Matthew R. Borths and Nancy J. Stevens: The first hyaenodont from the late Oligocene Nsungwe Formation of Tanzania: Paleoecological insights into the Paleogene-Neogene carnivore transition. PLoS ONE 12 (10), 2017, p. E0185301, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0185301

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g Matthew R. Borths and Nancy J. Stevens: The first hyaenodont from the late Oligocene Nsungwe Formation of Tanzania: Paleoecological insights into the Paleogene-Neogene carnivore transition. PLoS ONE 12 (10), 2017, p. E0185301, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0185301

- ↑ Nancy Stevens, Sifa Ngasala, Michael Gottfried Patrick O'Connor and Erik Roberts: Macroscelideans from the Oligocene of South Western Tanzania. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26 (3, suppl), 2006, p. 128A

- ^ A b Nancy J. Stevens, Patrick M. O'Connor, Eric M. Roberts and Michael D. Gottfried: A Hyracoid from the Late Oligocene Red Sandstone Group of Tanzania, Rukwalorax jinokitana (gen. And sp. Nov.). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (3), 2009, pp. 972-975

- ↑ Nancy J. Stevens, Michael D. Gottfried, Eric M. Roberts, Saidi Kapilima, Sifa Ngasala and Patrick M. O'Connor: Paleontological exploration in Africa: A view from the Rukwa Rift Basin of Tanzania. In: JG Fleagle and CC Gilbert (Eds.): Elwyn Simons, A Search for Origins. Springer, 2008, pp. 159-180

- ^ Erik R. Seiffert: Chronology of the Paleogene mammal localities. In: Lars Werdelin and William Joseph Sanders (eds.): Cenozoic Mammals of Africa. University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 2010, pp. 19-26

- ↑ a b Floréal Solé and Bastien Mennecart: A large hyaenodont from the Lutetian of Switzerland expands the body mass range of the European mammalian predators during the Eocene. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 64, 2019, doi: 10.4202 / app.00581.2018

- ↑ Kenneth D. Rose: The beginning of the age of mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2006, pp. 1–431 (pp. 122–126)

- ↑ Michael Morlo, Gregg Gunnell, and P. David Polly: What, if not nothing, is a creodont? Phylogeny and classification of Hyaenodontida and other former creodonts. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (3 suppl), 2009, p. 152A

- ↑ Floréal Solé: New proviverrine genus from the Early Eocene of Europe and the first phylogeny of Late Paleocene-Middle Eocene hyaenodontidans (Mammalia). Journal of Systematic Paleontology 11, 2013, pp. 375-398