Josephinism

Josephinism , derived from Emperor Joseph II , describes the consistent subordination of social affairs to the state administration of Austria according to the principles of enlightened absolutism . According to the principle, his mother Maria Theresa already implemented rather reserved secular changes from around 1750. The actual, far-reaching work of Joseph II in this regard extended over the years 1781 to 1790.

One differentiates Josephinism in the broader sense as a phenomenon of society as a whole from Josephinism in the narrower sense as a bundle of measures of state-controlled religious autarky.

Josephinism is one of the main sources for the Catholic Enlightenment .

General Josephinism

That of Joseph II under the motto “Everything for the people; reforms that have not been implemented by the people ”are to be understood as a“ revolution from above ”. Joseph took his measures following the rationalistic enlightened philosophers Hugo Grotius , Samuel von Pufendorf and Jakob Thomasius .

In order to make his interventions more effective, which he himself understood as the "benefit and benefit of the greater time" ( Age of Enlightenment ), he increased the possibilities of control and the bureaucracy. Thus, under his rule, the registration system or the house number system was introduced. On the other hand, it was Joseph II who initiated the end of serfdom with the subject patent in 1781 and thereby advanced to "Joseph the peasant liberator" in the later legend. He banned corset poles for girls, introduced the mandatory leash for dogs and abolished the civil death penalty - for reasons of utility, since it included workers in the delinquents, e.g. B. as a ship puller on the Danube, recognized.

His sense of utility moved him to build hospitals such as the General Hospital with the “ Narrenturm ” in Vienna instead of splendid castles .

The special Josephinism

Forerunner ideas of Josephinism in Austria go back to the 13th century. The administration of ecclesiastical properties was perceived as a problem, especially in the 16th century. In the second half of the 18th century the ideas of Febronianism were circulating, which tended towards a state church, as was realized in France with Gallicanism . State Chancellor Wenzel Anton Graf Kaunitz , who directed Austrian politics from 1753, was a personal friend of the Enlightenment Voltaire and an advocate of Gallicanism. Maria Theresa's court doctor Gerard van Swieten , a Jansenist , was president of the imperial commission for education. At the university, the Enlightenment had influential advocates in Karl Anton von Martini , Joseph von Sonnenfels and Paul Joseph von Riegger ; there the legal basis was created for Joseph's idea of a state church in his empire.

According to natural law , the main purpose of a state is the greatest possible happiness of its subjects. It sees religion alone as the institution which, by binding consciences, can counteract the obstacles relating to the neglect of duties and the lack of mutual benevolence among men. Consequently, the state sees religion as the main factor in education: "The church is a department of the police that has to serve the purposes of the state until the people are educated to the point that they can be replaced by the secular police." (Sonnenfels).

The scholar Riegger derived the supremacy of the state over the church from the theory of an original contract ("pactum unionis"), according to which the government exercises a certain ecclesiastical jurisdiction on behalf of all individuals, the "Jura circa sacra". Another scholar ( Franz Xaver Gmeiner ) formulated the theory that any legislation that contradicts the interests of the state contradicts natural law and consequently the will of Christ; as a result, the church has no right to enact such laws, nor can the state accept them.

Kaunitz reduced these basic rules to the statement: “The sovereignty of the state over the church extends to all church legislation and practice that is drawn up and practiced by people, and whatever else the church owes in terms of approval and sanction to secular power. As a result, the state must always have the power to limit, amend, or revoke previous concessions whenever reasons of state, abuses, or changed circumstances so require. ”Joseph II elevated these intentions to principles of government and treated ecclesiastical institutions as public affairs of the state.

Maria Theresa , the mother of her co-regent Joseph II, was largely reserved about Josephinism. From the perspective of state church law, Josephinism represents the attempt to place the spiritual authority of the church entirely at the service of the monarchy. This collided with the fundamental independence of the church, which is temporarily ready to compromise (e.g. through a concordat ), but does not want to forego this self-image.

The reforms

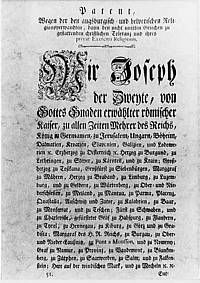

The reforms extended on the one hand to the Catholic Church within Austrian territory with the aim of creating a state church. Dioceses , church orders and foundations have so far been subject to a large number of sometimes overlapping foreign claims. The papal and all other ecclesiastical ordinances were subject to the imperial approval (placet); The bishops were responsible for making decisions about obstacles to marriage; Relations of the bishops with Rome and the ecclesiastical orders with their generals abroad were forbidden, partly for reasons of political economy. In 1783, during a stay in Rome, Joseph threatened the creation of an independent state church; he abolished the dependence on papal authority, and through an oath he bound the bishops to the state. The acceptance of papal titles and attendance at the German university in Rome were forbidden; A German university was created in Pavia in competition with the Roman one.

In addition, the case law was also redesigned. On July 22, 1765, the mayors were deprived of their previously unrestricted lower jurisdiction, and on May 4, 1766, they were transferred to judiciaries with legal training.

The principle of tolerance

The Tolerance Patent of 1781 initially (October 13) granted Greek Orthodox believers and Protestants the freedom to practice their religion and civil rights. The construction of Protestant tolerance houses (without a tower and an entrance leading to the street) was approved; Protestant children were also allowed to study at the university. However, the permission for conversion was restricted again; from 1787 onwards, those willing to convert had to take a 6-week religious lesson before leaving the Catholic Church.

The tolerance patent also opened up new opportunities for development for the Jews and found a lively echo in the Haskala stream of Jewish enlightenment at the same time . However, there was no uniform patent for this denomination, but those that were adapted to the local conditions of the provinces and were introduced at different times:

- Bohemia on October 19, 1781

- Silesia on December 15, 1781

- Vienna and Lower Austria on January 2, 1782

- Hungary on March 31, 1783

- Galicia was not actually introduced until September 30, 1789

The Masonic patent of Joseph II of December 11th, 1785 subjected the lodges to meticulous state control, an Austrian grand lodge was established, many Viennese lodges merged or ceased their masonry activity, the number of lodges in the crown lands was limited to one each, which in turn was hierarchically the Should be subordinate to Grand Lodge. Potentially conspiratorial groups, regarded by Joseph as enthusiastic and dangerous to the state, which deviated from the regular high-level masonry of the Grand Lodge, such as the Gold and Rosicrucians , the Asian Brothers and the clergy , were thus implicitly banned. Joseph's Masonic patent, in which masonry is referred to as "Gaukeley", disappointed and perplexed his former supporters. It is also to be seen in the context of the conspiracy obsession that was unleashed in Europe with the discovery of the Illuminati Order (1784).

The principle of centralism

This relief went hand in hand with a countless number of meticulous formal religious regulations. For example, on August 23, 1784, Joseph II ordered the closure of all local cemeteries for reasons of "hygiene". The funeral rite was henceforth to be carried out without a fixed coffin by a reusable, collapsible community coffin . He withdrew this decree after a short time due to opposition from the population.

In order to counteract the rampant pomp that arose with the Counter-Reformation , Joseph II issued ordinances including the number and length of candles, the type of sermons, prayers and chants. All superfluous altars and all splendid vestments and pictures had to be removed; various passages in the breviary should be pasted over. No dogmatic questions should be discussed in the pulpit; Rather, they expected public announcements and practical advice on cultivating fields, for example. "Our brother, the sacristan," called Frederick the Great Joseph, whom he saw as the creator of a purified worship service.

Abolition of monasteries and religious funds

prehistory

In order to support the Counter-Reformation , Bishop Melchior Khlesl, with the support of Ferdinand II , promoted the settlement of several orders in and around Vienna, and existing orders expanded their monasteries in the Baroque style. The start of the monastery initiative was the renovation of the Franciscan Church, which began in 1603 . With the support of loyal aristocratic families, this turned into a real Austria-wide “monastery boom”. In the residential city of Vienna with its suburbs and suburbs there were 25 monasteries in 1660, which grew to 125 in 1700. In 1765 there were 7,200 monks in Lower Austria, 1,500 of them in Vienna. Many start-ups were generally poorly funded and became a burden for the population through begging. In Vienna itself (today the Inner City ) there were 13 men's and seven women's convents before 1782, of which three men's and six women's congregations were abolished. A total of 18 monasteries were closed in the vicinity.

The Josephine basic idea - reducing the number of monasteries and instead increasing the number of parishes - was already adopted by his grandfather Charles VI, who was entirely in the tradition of Baroque Catholicism . divided. Corresponding measures were started under Empress Maria Theresa . In 1751 she announced a major remedy for orders and monasteries, the basic tendency of which was to deprive monasteries and foundations of their privileged position and to see the conventuals as citizens and subjects of the state ( state church ). Attempts were also made at that time to limit the number of monks. The age of profession was raised to 24 years. From 1767, monasteries were only allowed to accept novices as replacements for members of the order who had died or were terminally ill. In Lombardy there were 80 abolition of the monastery before 1780. In the core countries this did not begin until 1773, when Maria Theresa reluctantly dissolved the Jesuit settlements in Austria after the abolition of the Jesuit order by Pope Clement XIV . The order lost 4 houses in Vienna as a result.

Josephine Church Reform

Joseph viewed the state as the administrator of the worldly goods of the church and formulated this idea in a law that summarized the property of all churches, sacred buildings and furnishings in his territory into a large property for the various requirements of practical worship in a so-called religion fund. The sacred buildings, the entire ecclesiastical property, the chapels, the abbeys and monasteries and all sacred ornaments were transferred to a new property.

Joseph also took action against the monasteries, which he regarded as "sources of superstition and religious fanaticism". In the Austrian hereditary countries and Hungary, their number had grown to 2,163 with 45,000 members in 1770. In 1782, the decision to repeal initially affected the contemplative orders, which the emperor regarded as "useless". From 1783, due to the idea of the religious fund established in 1782, the so-called “wealthy prelates” became the main target of his repeal measures. A journey from Pius VI. to Vienna in March 1782 came to nothing. Of 915 monasteries (762 men, 153 women) from 1780 in German-speaking Austria (including Bohemia, Moravia and Galicia), 388 have been preserved. As a result of these measures, the “Religion Fund” grew to 35,000,000 guilders.

The abolition of monasteries and hermitages did not result in any growth in the fund, and the abolition of the Orders in 1783 also showed financial losses. Half of their property was devoted to educational purposes, the other half "with all its ecclesiastical privileges, income and goods" transferred into a new "Sole Beneficiary Association", which had the character of both an order and a charitable institution and ended social hardship should.

New churches

The abolition of branch churches and chapels enabled Joseph to found new parishes. The state also demanded the training of the clergy and their commitment in the communities in order to guarantee both the worship and social welfare. Each local church should be accessible to each parishioner over a distance of at most one hour; one church should be available for every 700 souls.

Supply principle

Joseph set a fixed amount for pensions for former monks and for salaries of pastors. Foundations without a pastoral activity, income in larger churches and from all canons above a locally determined number fell to the religious fund, the income was distributed among the pastors. A maximum amount was set for the equipment of the dioceses, the surplus flowed to the religious fund, as well as the income from vacancies .

The religious fund had to pay for the cost of appointing the clergy under state control, for the general seminars and the support of the young clergy, the institutes for the practical training of priests and the support of the retired priests.

The implementation of the Josephine reforms and the abolition of the order met with popular resistance. The design of masses and altars, oratorios, chapels and orders, processions, pilgrimages and devotions were restricted by the new service rule.

The transfer of the church property into a single fund was practically impossible. In the case of monastery ownership, it represented a great loss. The assets of each church and foundation had to be publicly declared, converted into a government loan and invested in the religious fund.

A tax was levied on church property that had escaped secularization . Since 1788 it was imposed on the still existing order and the secular clergy.

General seminars

Maria Theresa's “study reform”, Rautenstrauch's “curriculum” in 1776 and the introduction of Riecher's “Handbook of Canonical Law” paved the way for the creation of general theological seminars. Joseph founded twelve: in Vienna, Graz , Prague , Olomouc , Pressburg , Pest , Innsbruck , Freiburg , Lemberg (two for Galicia - Greek and Latin rite ), Leuven and Pavia .

In 1783 all monastery schools and episcopal seminars were closed as part of the “ monastery tower ”. The "general seminars" were attached to the universities as convikte, but had their own theological courses. Five years of study took place in an episcopal training institution (priestly house) or a monastery. The basic rules of the seminary directors were liberal, according to the rationalist theology of the state. A sharp opposition arose particularly on the part of the church foundations and monasteries. The novices, brought up at their own expense in the general seminars, often lost their religious vocation.

literature

- Helmut Reinalter (Ed.): Josephinism as Enlightened Absolutism. Böhlau-Verlag, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2008, ISBN 978-3-205-77777-9 .

- Friedel Hans-Josef Dapprich: Josef II. And the spiritual emancipation of Judaism in the Eastern European countries of the Habsburg Empire. GRIN Verlag, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-656-48862-0 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ austria-lexikon.at

- ^ Project cluster Jewish Holy Roman Empire. University of Vienna, accessed on February 6, 2015.

- ↑ Tolerance patent for the Jews in Vienna and Lower Austria (PDF) University of Graz - jku.at, accessed on February 6, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d Peter Csendes: The early modern residence (16th to 18th century). (= Vienna: History of a City. Volume 2). Böhlau Verlag, Vienna 2003, ISBN 3-205-99267-9 , pp. 333, 344. ( limited preview in Google book search)

- ↑ Martin Mutschlechner: Pietas Austriaca - The struggle for souls - Habsburg and the Counter Reformation. ( habsburger.net ( memento of November 10, 2011 in the Internet Archive ))

- ^ A b Karl Vocelka: Abolition of monasteries in Austria - "useful citizens" instead of monks and nuns.

- ^ Karl Gutkas: History of the Province of Lower Austria. 6th edition. Volume 1, Niederösterreichisches Pressehaus, 1983, ISBN 3-85326-668-1 , p. 353.

- ↑ Andreas Freye: The Josephine reforms in Austria under Maria Theresa and Joseph II. With the focus on church reform . GRIN Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-638-67098-2 , p. 18 ( Google book preview )