Sarcophagus of the Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa

The sarcophagus of the Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa is an Etruscan artifact from the 2nd century BC. BC and was discovered in 1886 near Chuisi. Today the sarcophagus is in the British Museum in London . It is one of the most important works of the late Etruscan sepulchral culture .

Description of the sarcophagus

The 1.83 m long, 70 cm wide, 42 cm high and 750 kg heavy sarcophagus was made of terracotta and is covered with a white coating that is supposed to imitate marble . This layer was painted with intense bright colors, of which there are still paint residues. The sarcophagus is decorated in alternating sequence with architectural elements ( triglyphs ) and floral ornaments ( rosettes ). The lid is divided into two halves in the middle.

On the sarcophagus a young, female person is depicted, who is lying on a mattress and is supported with her left elbow on a pillow. In her left hand she holds an opened mirror. With her right hand she holds a veil pulled over the back of her head. She wears gold jewelry, including finger rings, earrings, a necklace, bracelets on her upper arm and forearm and a diadem on her head . Her auburn hair is parted in the middle and combed back in fine waves. The sleeveless floor-length dress is gathered at the waist by a knotted ribbon, the ends of which hang down as an ornament. Over it she wears a knee-length thin coat. The clothes throw fine folds and play around their lush, shapely body. The figure is larger than life because it lies on a 1.83 m long sarcophagus with the knees slightly drawn up, i.e. about 2 m tall when standing.

It is unclear on which occasion or event the deceased is depicted. A banquet in the realm of the dead, a regularly recurring theme in tomb paintings, seems possible. However, apart from the lying position, there is no further indication of a feast. Etruscan women, unlike Greek women, were allowed to lie at the table. Due to the veil and festive attire, it is more likely that the deceased is depicted as a bride and that the occasion is her wedding. Maybe Seianti is already in the underworld and looks up from her mirror as if she was expecting someone. Recent research has shown that what used to be interpreted as farewell scenes in tomb paintings are actually greetings to welcome newcomers.

Classification of the sarcophagus

In terms of style and technology, the sarcophagus corresponds to the sarcophagus of Larthia Seianti , which comes from a multi-chamber grave near Chuisi and is now in the National Archaeological Museum of Florence . Both people probably come from the same aristocratic family. The construction of the burial chambers and the style of the art objects found in them date back to the 2nd century BC. Chr. Some recent research dates both sarcophagi to around 150 BC. According to another opinion, the sarcophagus of Larthia Seianti is 20 to 30 years older and dates from 170 to 180 BC. Chr.

The two Seianti sarcophagi are unusually finely crafted and richly decorated compared to other terracotta sarcophagi. The colors used, such as the so-called Egyptian blue, of which remains can be found on the mirror, were precious and expensive. In general, painting sarcophagi was not the rule, as numerous specimens from the area attest. The production of the sarcophagus also required great skill, as the clay sculpture had to be supported with wooden struts or latticework before burning due to its own weight. The figure of the Seianti was made in a total of five parts, which were put together after firing.

In Etruria, various types of local stone were used for urns and sarcophagi, but other than alabaster , which was mainly grown in the region of Volterra , they were difficult to work with. The Etruscans had no access to marble. The marble quarries in Carrara were not opened until the 1st century BC. Opened up. Terracotta was therefore often the preferred material for the ornate sculptures with which the Etruscans also decorated temples, while statues, few of which have survived the ages, were very often made of bronze.

Inscription on the sarcophagus

Before the clay was burned, an Etruscan inscription was carved into the base of the sarcophagus, written from right to left in mirror-inverted letters in accordance with the writing habits of the Etruscans:

The reading of the inscription recognized today is:

- SEIANTI HANUNIA TLESNASA

SEIANTI is a locally common gentile name from this period. At first it was assumed that the second name begins with the letter Θ (theta) and therefore reflects the first name THANUNIA. The mention of the gentile name before the first name was not unusual in Etruscan naming . In the more recent research, however, one comes to the conclusion that this letter is an Etruscan H and the name given is HANUNIA. The discovery of six other inscriptions with this name in the vicinity of Chiusi, including the name of a VELIA SEIANTI HANUNIA, suggests that HANUNIA is not a first name but a gentile name. It is now believed that the Seianti and Hanunia were two important Etruscan families, and that the deceased was descended from these families. Since TLESNASA seems to be the gentile name of the husband, three gentile names are listed in the inscription without the first name of the deceased being mentioned.

The inscription could suggest that the deceased could read and write herself. Since objects such as mirrors, vessels and looms were occasionally provided with the names of their female owners and Etruscan women enjoyed a high social reputation among the aristocracy, one can assume that at least some of the Etruscan aristocrats could read and write. Since Seianti apparently belonged to an important and wealthy family, she should have been able to read and write.

Examination of the skeleton

The skeleton of Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa can still be found in the sarcophagus. The deceased is evidently depicted as highly idealized and rejuvenated, because the skull found in the sarcophagus , on which several teeth are missing and the remaining teeth are worn, suggests an older woman. The examination of the skeleton led to the result that the woman was corpulent at the time of her death, about 1.54 m tall and between 50 and 55 years old, which corresponded to the average height and life expectancy of a woman at the time. A radiocarbon study showed that the person lived between 250 and 100 BC. Chr. Died.

In 2002, a team of experts led by Judith Swaddling carried out an extensive medical examination of the skeleton and came up with a detailed result. Apparently, as a young woman, the deceased had suffered trauma to the soft tissues of her right pelvis and lower lumbar spine . The injuries likely resulted in bruises , necrosis and changes in bone tissue, and caused lifelong pain and restricted mobility in the hip and pelvic area. The deceased also suffered from right temporomandibular joint damage , which occurred around the same time, leaving her with joint pain and abscesses . She may have had to eat specially prepared soft foods well into old age and may have difficulty speaking. She had also suffered a fracture of the orbital bone under her right eye in her youth .

The injuries mentioned presumably all occurred at the same time and can be traced back to an accident. Seianti could hit a hard object with his right side, e.g. B. fell a rock or tree trunk. In doing so, she may have lost some teeth. A riding accident can be suspected as the cause of the injuries. Despite the limitations, Seianti was in relatively good health, had given birth to at least one child, and may not have developed scoliosis and arthritis until old age . As an aristocrat, she probably had enough servants to help make her life more comfortable.

Facial reconstruction was performed based on the skull by gradually covering a cast of the skull with layers of clay, depending on the thickness of the skin and muscles, and taking into account the age and health of the person. The result shows a certain correspondence between the facial features of the figure and the sitter, which suggests a deliberately portrait-like reproduction of the deceased. This hint of realism in Etruscan art distinguishes the work from the Hellenistic creations of this time, which, firmly rooted in the Greek tradition, tend towards idealization. According to another opinion, there is a certain discrepancy between the reconstructed face of the Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa and its idealized image on the sarcophagus, so that one cannot assume a portrait-like representation as a feature of the grave sculpture in the Hellenistic period.

Discovery of the grave

In 1886, 6 km west of Chiusi at Poggio Cantarello, a single-chamber grave was discovered that contained the sarcophagus of the Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa. A long corridor ( dromos ) leads to the burial chamber, on the back wall of which the sarcophagus stood and which almost filled the back wall in width and height. The size of the corridor leading to the tomb suggests that the large, heavy sarcophagus was carried in pieces into the chamber and then assembled there.

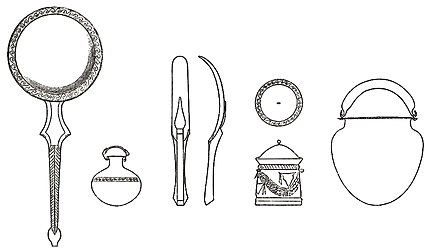

Next to the sarcophagus on the right wall of the burial chamber, five silver objects were fastened with iron nails, including a mirror. The thin sheet of silver from which it is made suggests that it was not made for everyday use, but only as a sepulcral decorative piece. The edge of the mirror, decorated with a wave pattern, is gilded.

The other found objects included an ointment vessel ( alabastron ) with a gold-plated wavy band, a scraper ( strigilis ), with which cleaning oil, sweat and dust were scraped from the body, but which could also have been used for depilation, a small bucket ( situla ) and a container for pomade or make-up with a lid ( pyxis ). The garlands of the can and the edge of the lid are also gold-plated. The mirror was found attached to the wall when the tomb was discovered. The other four objects had fallen to the floor after their nails rusted.

The rarity and size of the sarcophagus, which certifies access to the best craftsmen, and the construction of an individual grave for the deceased attest to the wealth and high status of this Etruscan aristocrat. Usually a whole family shared a multi-chamber grave in a public cemetery area. Individual graves, however, are likely to have been on private property. However, it is not clear why the grave goods of the deceased were so economical compared to their relative Larthia Seianti, whose grave was housed in a family crypt, but contained significantly more grave goods.

The discovery was first reported in 1886 in the " Anmerkungie degli scavi di antichità" (news about ancient excavations) and in the communications of the Imperial German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department . In German-speaking countries, the discovery was first mentioned in 1891 in Volume I, Ancient Monuments, of the Imperial German Archaeological Institute . First the sarcophagus came into the possession of the classical archaeologist Wolfgang Helbig . In 1887 the British Museum in London was able to purchase the sarcophagus.

Historical background

Chiusi (Etruscan Clevsin ), located in the hilly landscape of northern Etruria, was one of the most important Etruscan cities and was one of the oldest settlements of the Etruscans. She belonged to the League of Twelve Cities . Lars Porsenna came from Chiusi , who lived in the 6th century BC. BC ruled the city and was able to conquer Rome. Relations with Rome were not always hostile. As of 390 BC Chr. Chiusi was attacked by the Gauls , the Romans came to the rescue, whereupon the Gauls turned against Rome. During the 4th century BC A decline in power in the city becomes archaeologically visible. At the beginning of the 3rd century BC The area around Chiusi was the scene of the fighting of the Romans against Gauls, Etruscans and Umbrians ( Battle of Sentinum ). The Seianti family may have originally come from the nearby Sentinum and may have fled from there to Chiusi after the battle.

The deceased probably came from the same aristocratic family as Larthia Seianti. Both women had lived in a turbulent time in which unrest and wars, including the 2nd Punic War , swept across central Italy and Chuisi came under Roman influence. With the construction of the Via Cassia , northern Etruria was connected directly to mighty Rome and colonized by Roman settlements. Often these were agricultural settlements that were managed by former Roman legionaries ( veterans ). The north Etruscan cities maintained their aristocratic-oligarchic order. Apparently the Seianti family also managed to maintain their prosperity. This made it possible to set a monument to the two women with magnificent graves. Sarcophagi of this kind are among the last genuinely Etruscan art creations. Already 150 years later the Etruscan culture had completely dissolved in the course of the Romanization , language and art had perished.

Remarks

- ↑ Judith Swaddling, John Prague (ed.): Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa: The story of an Etruscan noblewoman . British Museum Press, London 2002, ISBN 0861591003 .

- ↑ Photograph of the facial reconstruction on the website of the British Museum in London (November 20, 2017)

- ↑ Istituto nazionale di archeologia e storia dell'arte (ed.): Notes degli scavi di antichità . Reale Accademia dei Lincei, Rome 1886, pp. 353-356. ( online )

- ^ Imperial German Archaeological Institute (ed.): Bullettino Mitteilungen des Kaiserlich German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department. (Volume I). Verlag von Loescher & Co., Rome 1886, pp. 217-219. ( online )

- ^ Imperial German Archaeological Institute (ed.): Ancient monuments (Volume I). Published by Georg Reimer, Berlin 1891, pp. 9-10. ( online )

literature

- Friederike Bubenheimer-Erhart: The Etruscans. Philipp von Zabern, Darmstadt 2014, ISBN 9783805348058 , p. 135.

- Stephanie Lynn Budin, Jean Macintosh Turfa (Eds.): Women in Antiquity: Real Women across the Ancient World. Routledge, Abingdon & New York 2016, ISBN 9781138808362 , pp. 769-780.

- Sybille Haynes : Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History. Getty Publications, Los Angeles 2000, ISBN 0892366001 , pp. 336-339.

- James Thomas Hooker (Ed.): Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet. University of California Press, Berkeley 1990, ISBN 0520074319 , p. 361.

- Christopher Smith : The Etruscans. Reclam, Stuttgart 2016, ISBN 9783150204030 , pp. 155–156.

- Jean MacIntosh Turfa (Ed.): The Etruscan World. Routledge, New York 2013, ISBN 9781134055234 , pp. 860-861.