Chess computer

Chess computers (also called chess calculators ) are specialized computers for playing chess . They contain a chess program built in as firmware and form the device base for computer chess .

Early history

The Turk"

The first machine that supposedly could play chess was the "Chess Turk " by Wolfgang von Kempelen (1734–1804) around 1770 . The machine consisted of a Turkish-looking life-size figure sitting on a chair by a desk-sized cupboard. The cabinet contained intricate mechanics that were shown before each game by opening the doors in a set order to prove the absence of people. The machine could not play chess on its own, however, because the machine was " faked " - as it later became a popular saying:

- A (short) chess player was hidden inside who had to change his position during the inspection and then let the seated Turkish figure make the moves using a mechanism to play. The positions of the chess pieces, which the hidden player could not see, were transferred to the inside via magnetic plates at the foot of the pieces.

Some of the best chess masters of the time served the Turks, who, according to tradition, very rarely lost a game. Most recently, the French Schlumberger served him, including on a multi-year tour through the United States. His death in 1838 put an end to the active career of the machine, the secret of which was officially never revealed. Celebrities like Maria Theresa , who commissioned the machine, and Napoleon also played against the chess Turk; The latter lost three games against the "machine", which is said to have been controlled by the first significant German-speaking chess master Johann Baptist Allgaier at the time .

Torres' rook endgame machine

The Spaniard Leonardo Torres Quevedo constructed the first real chess-playing machine . As a specialist in control systems, he built an electromechanical machine called El Ajedrecista ( German "The Chess Player" ), which could carry out the final king and rook against king. The device was first demonstrated in 1914 in Paris, it is in the Polytechnic University of Madrid . Although it was not yet a computer, it was an electrical engineering masterpiece that combines mechanics and relay technology . However, the machine did not always solve the problems posed optimally in the fewest possible moves. From that time on, mechanical chess research was largely idle until digital computers were developed in the 1950s and electronics were supposed to replace mechanics here. How El Ajedrecista works was described in BYTE magazine in the article "ANTIQUE MECHANICAL COMPUTERS: The Torres Chess Automaton".

Mainframe and special computers

The history of the chess computer is closely related to the development of chess programs and can usually no longer be treated separately. Therefore, only the hardware is described below.

Belle and Cray X-MP

Belle was a hard-wired machine developed by Ken Thompson and Joe Condon at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey in 1979 . It could generate up to 180,000 positions per second and reached a search depth of up to nine half-moves. Belle dominated the computer chess scene until 1983. In the same year she was awarded the title of National Master by the US Chess Federation. This was the first award of its kind for a chess computer.

Robert Hyatt , a Mississippi professor, had been working on a program called Blitz since 1975, and in 1979 he contacted the research department at Cray , which provided him with a top-level computer ( Cray-1 ). Working with Al Gower, a music professor and correspondence chess player, Hyatt developed Cray Blitz . But despite the computing power of such a supercomputer (Cray-1 was the fastest computing system in the world at the time), Belle could not be defeated.

It wasn't until Cray X-MP that Belle was beaten by Cray Blitz in 1983 . Cray Blitz was programmed in Fortran , C and Cray assembler . Cray X-MP had 16 processors and an output of 13,000 Mips. In this configuration, the computer cost about $ 50 million. The chess calculations were distributed to the processors with the help of a special algorithm. Cray Blitz was world champion computer chess in 1983 and 1986 . Cray X-MP was not a chess computer in the narrower sense, but a universal computer on which other programs usually ran. The Crafty program is a direct descendant of Cray Blitz and is still being developed by Robert Hyatt.

Despite the victory of the universal machine Cray X-MP ( Belle also won again in other games ), the cost-benefit ratio showed that there was still enormous potential in special hardware: Belle only cost a thousandth of a Cray machine.

HiTech

At Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh , USA, Hans Berliner built a special computer called HiTech . Although Berliner was more drawn to the B strategy , he built a brute force computer with 64 processors that examined 120,000 positions per second. Despite some successes, the big breakthrough did not materialize.

Deep Thought and Deep Blue

Deep Thought was a pre-development of Deep Blue , the super chess computer from IBM , the last special computer of its kind. Since PC chess programs easily beat all human chess players, the interest in chess-playing mainframes and special computers has also declined.

Hydra

The Hydra chess computer is a powerful machine. It is a mixture of standard hardware ( Linux - computer cluster of 32 Intel Xeon processors) and 32 FPGA cards for the position evaluation. Hydra tries to parallelize the tree search . It is developed by the Austrian “Chrilly” Donninger , the Germans Ulf Lorenz and Christopher Lutz and the company PAL Computer Systems from Abu Dhabi.

Chess computers for home use

- Some examples

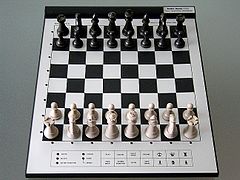

With the Fidelity Chess Challenger 1, the first commercial chess computer appeared in 1977. This was the beginning of a stormy development in the 1980s of ever new and more powerful chess computers. With early chess computers, one's own move still had to be entered using the keyboard.

However, in 1983 Fidelity Elite A / S was able to recognize the movement of the figures themselves. With today's chess computers, which usually have the shape of a chess board, this can be achieved, for example, by means of small magnets in the foot of the figure.

The development of chess computers in the GDR followed a special path , where the emphasis was placed on the development of chess computers for high demands, in particular also for the purpose of foreign exchange income from exports to western countries.

Chess robot

In 1983 the MB Milton came onto the European market. This had a robot unit in the lower part of the housing, which was mechanically constructed like a plotter . This unit could pull the pieces over the chessboard from below using an electromagnet. The MB Milton was called "MB Grandmaster" on the American market. Both were largely identical to other chess robots such as the "Fidelity Phantom 6100" or the "Phantom 6126 Chesster" (Eyeball). Another design based on the same principle was implemented in the "Excalibur Mirage". Other companies built more elaborate chess robots by moving the pieces via a robot arm attached above the chess board. Examples of this are the “Novag Robot Adversary” or the “Excalibur Talking Robotic Chess 740”, which, however, never went into series production.

Current devices

Micro chess computers are mainly sold in the low price segment. Current devices from mass production dispense with mechanical extras and focus on training functions, for example stored exercises and warnings in the event of gross errors. The market niche for chess computers with particularly high-quality equipment is mainly served by the second-hand market or within a collector's scene. In addition, there are small series of new devices with special versions of software chess engines.

In 2016 Digital Game Technology (DGT) presented the DGT Pi Chess Computer , a chess computer based on the Raspberry Pi . This is integrated in a chess clock and uses its display. The moves are entered through a chessboard with figure recognition, also from DGT, which is connected via Bluetooth or USB . One of the chess engines used is Stockfish . It is worth mentioning that the firmware used , PicoChess , is freely available.

Competitions

The world's first major computer chess championship took place in September 1970 in New York under the name 1st ACM United States Computer Chess Championship . This resulted in the North American Computer Chess Championship (NACCC, German " North American Computer Chess Championship " ), which until 1994 was mostly held annually. In addition, from 1980 to 2001 the micro-computer chess world championship (“micro-world championship” for short) was organized. Participants often competed with equipment specially tuned for the tournament. The most successful World Cup chess computers contained programs by Dan and Kathe Spracklen ( Fidelity , CPU 6502 , origin Sargon ) and Richard Lang ( Mephisto , CPU 68000 , origin Psion ).

The world's most important and still held computer chess tournament, the World Computer Chess Championship (WCCC) , German "World Computer Chess Championship" to which both supercomputers are permitted current chess programs as well as all kinds of chess computers. At the 7th World Computer Chess Championship in 1992, a “micro”, the ChessMachine Gideon 3.1 by Ed Schröder (also marketed as Mephisto RISC II chess computer) succeeded for the first time to distance the mainframe and special computers and to achieve the title of world computer chess champion.

From the beginning of the 1990s, personal computers were increasingly used for chess programs . From that point on, they provided more powerful and portable platforms. The market for high-priced micro chess computers collapsed, and from then on PC chess programs such as HIARCS , Rebel , Fritz , Genius or MChess dominated. From 1994 onwards, the Mikros no longer only took part in their own world championships, which continued until 2001.

World Microcomputer Chess Championship (WMCCC)

Alexander Canetti published an overview of the beginnings of the microcomputer chess world championships in 1988, beginning in 1980 in London. Mephisto had to wait until 1983 for his first assignment. In 1981, the disapproval of Mephisto turned into a scandal. In order to compare the playing strength of micro-chess computers and PC programs, these are given Elo numbers based on their games , which are maintained in the context of the SSDF list .

Chess computer vs. human

In 1996, Deep Blue became the first computer in the world to beat a reigning world chess champion , Garry Kasparov , in a game with regular time controls .

literature

- Dieter Steinwender , Frederic Friedel : Chess on the PC - bits and bytes in the royal game. Pearson Education, 1998, ISBN 3-87791-522-1 .

- NH Yazgac: Chess computers, what they can really do. Beyer Verlag, Hollfeld 1989, ISBN 3-88805-082-0 .

- Hans-Peter Ketterling, Frieder Schwenkel, Ossi Weiner : Chess on the computer. (= Goldmann advisor ). 1983, ISBN 3-442-10861-6 .

- Jürgen Reelitz: chess computer, your partner u. Trainer for game and Tactics. Maier Verlag, Ravensburg 1985, ISBN 3-473-43153-2 .

- Danny Kopec : Chess Computers - A critical descriptive analysis of the currently available commercial chess computers. 1985. PDF; 1.4 MB

Web links

- Current SSDF list

- Chess computer oldies with Kurt Kispert

- Heiko Berger's Chess Computer Museum

- Chess computer story by Karsten Bauermeister

- schach-computer.info Wiki - The wiki for chess computers

- Chess computer instructions from Alain Zanchetta

- Literature online: Claude E. Shannon (1950). Programming a Computer for Playing Chess

- Information about chess computer with robotic arm

- Microchess - the first microcomputer chess program

- 9th Computer Chess World Championship from June 14th to 20th, 1999 in Paderborn Report on TeleSchach

Individual evidence

- ^ Friedel Steinwender: Chess on the PC. Verlag Markt und Technik, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-87791-522-1 , pp. 27-30.

- ↑ Madeleine Amberger: Dimensions - the world of science: three of a kind against flush. With poker, researchers are further developing artificial intelligence. oe1.orf.at, radio broadcast, August 20, 2015, 7:05 p.m. (25 min.)

- ↑ Byte Magazine Volume 03 Number 09 - Graphic Manipulations . September 1978 ( archive.org [accessed September 8, 2019]).

- ↑ Crafty ( Memento from March 28, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Dieter Steinwender , Frederic Friedel : Chess on the PC - Bits and Bytes in the Royal Game. Pearson Education, 1998, ISBN 3-87791-522-1 , p. 76.

- ↑ Otto Borik : Micro World Cup in Rome - A review. In: Computer chess and games . No. 6, 1987, pp. 32-36.

- ↑ Dan and Kathe Spracklen : Sargon - A Computer Chess Program. Hayden Book Company, 1978, ISBN 0-8104-5155-7 .

- ↑ Alexander Canetti: The History of the Chess Computer World Championships . In: Chess Echo . Volume 2, 1988, pp. 81 and 82 (table and report).