Schleinitz Castle

Schleinitz Castle is a late Gothic former moated castle in the Renaissance style in the Ketzerbachtal , 4.5 km south of Lommatzsch and 13 km west of Meißen and was one of the largest manorials in Saxony in terms of area until 1945 .

Building description

The late Gothic building was built at the end of the 15th and beginning of the 16th century in place of a possible moated castle with two round towers in front . The bottom of the trench that is visible today was at least three meters deeper at this time, as the pond behind it, which was connected to a dam, was still four meters deep in 1923. The two towers, which are still visible in the moat area, are connected by a defensive wall . Between the two towers is the inner courtyard, remains of the former kennel . The late Gothic building concept never saw flooding and use of the surrounding trench as a moat in front, but pursued already formed by the construction of the Albrechtsburg Meissen given not only militarily aligned lock concept , but focused on the architectural power of representation of the manorial system . Of the originally Gothic version, only the left wing with the so-called basement is preserved today, which forms the actual ground floor on today's trench floor. It is the former house chapel with a cell vault . Your choir is closed with three sides of the octagon. In the axis of the chapel there are two windows with curtain arches and strong overlapping of the profiles, which brings the Schleinitz builder closer to Arnold von Westfalen . Up until the Reformation , this stately chapel was served by a special altarist , the pastor from Leuben had to preach here, or the schoolteacher from Leuben had to work as an organist in order to, at the request of the landlord, his family and subordinates with the service , as well as the Office to supply communion . The wall cupboard cut into the stone in the chapel shows the year 1518 and probably dates from the time of the previous building of the castle that is visible today. The upper floor of the left tower, in which the circular shape of the lower floor of the tower was given up, also dates from the same time as the chapel. In the second half of the sixteenth century, presumably as a result of a fire, a graceful arched hall was built above the basement as today's ground floor, and above it, in turn, two upper floors, which are divided into an almost square central building and a right wing, the architectural complement to the Renaissance style Gothic left wing form. Otherwise the entire construction is kept simple. The often described Gothic gable in front of the gable roof already shows the transition from the curved volute gable, which was often used in the Renaissance . Two original Abtritterker have been preserved on the north facade . The right tower is still used as a kitchen room today. A stone bridge has been leading over the former moat since 1781 and two side stairs lead down into the moat on both sides on the castle side. In 1905 major renovations were carried out under the Dresden architect Hans Gerlach. So the large two-storey hall was built in the central building, which had to give way to an original late Gothic spiral staircase. Above the central building, the so-called Dresden room with a painted wooden ceiling in dark gray, brown and yellow ornaments reminds of this time of the renovation in 1905.

Orangery

The garden house, which was built as an orangery and faced in a spacious French park, is an elongated building with a simple design. On the ground floor there were large openings to the south and on the upper floor there was the famous Schleinitz library with over 3000 volumes by Dietrich von Bose from 1690, about which the Saxon historian Johann Friedrich Ursinus , (* August 15, 1735 in Meißen , † 9 January 1796), pastor from Beicha. The valuable book inventory included a Bible by Hans Lufft from 1561 from Wittenberg and a handwritten letter from Nikolaus Selnecker . Today the building is used exclusively for residential purposes. The remains of the theater that Cornelius Gurlitt saw in 1923 can no longer be found.

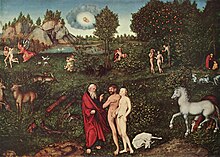

Lucas Cranach the Elder Ä. paradise

When Otto Eduard Schmidt entered the castle and garden house, which had been abandoned for years, in 1904 on his forays into the Electorate of Saxony, he recognized an original painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder in the art collection of the former owner of Bose, among other things on the winged snake . Ä. Cranach depicted paradise as a Garden of Eden with a multitude of animals living peacefully together. The picture was thus available in two original versions, one of which is still part of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Both are identical except for the accentuation of the event and further show in individual Protestant-influenced interpretive scenes the creation of Adam by God , the fall of man and the expulsion . In 1928 the owner, Baron Stephan von Friesen, gave this painting to the Dresden Gemäldegalerie to have it restored, as the panel had suffered from the paint cracking and was consequently not intact. The gallery director responsible there, Hans Posse , immediately recognized the value of this previously unknown Cranach and tried to acquire the picture for the Dresden picture gallery. After further negotiations, Baron Stephan von Friesen sold the picture in the Dresden Gemäldegalerie in 1928 for 15,000 marks, where it was immediately presented in the permanent exhibition. This picture, like other works of art, was stolen by the Soviets in 1945, then returned and has been shown in the permanent exhibition from 1958 until today.

Schleinitz estate

Immediately to the northeast, looking towards the castle, there is the former 280 hectare farm estate connected to the castle, an ensemble of farm buildings with former barns, malt houses, bakery houses and stables that are now used as apartments. The estate included 186 hectares of fields, 21 hectares of meadows, 65 hectares of forest and 8 hectares of ponds. A stone walled in in the courthouse dates parts of the complex to the year 1558. Traditional rural use no longer takes place in the sparsely populated location. In the old granary of the manor, the sponsoring association, which was at times the largest local employer with sixty ABM employees around 2000, set up a museum for rural customs, in which work equipment and tools from rural household, field and livestock farming are presented as museum exhibits become. There are also demonstration workshops for shoemakers, saddlers and blacksmiths. The courthouse on the axis of the palace, which was last renovated in the 16th century as a cellar house solely for the purpose of storage, was named after the 18th century as the local court and judge seat for inheritance and court matters of the Schleinitz manor . The octagonal roof turret with clock, lantern and pear-shaped hood comes from later construction periods.

history

In Schleinitz a manor was first documented in 1231, a knight's seat in 1443 and an old manor in 1551. The rule exercised inheritance and higher jurisdiction. In 1696 Schleinitz was part of the area of responsibility of the Meißen office.

Von Schleinitz (1255–1594)

The von Schleinitz family is a Saxon nobility and was first mentioned in a document in 1255. The family's property complexes extended as far as northern Bohemia.

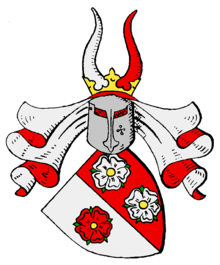

coat of arms

The coat of arms shows three roses in a split shield and has a red buffalo horn on the right and a silver buffalo horn on the left.

From Loß (1594–1664)

The noble family von Loß belonged to the power elite of Saxony. Christoph von Loß (1574–1620) had become the heir of his father-in-law Abraham von Schleinitz through his wife Maria and thus became the Protestant landlord of Schleinitz Castle on the eve of the Thirty Years' War . He was the diplomatic counterpart to his brother Joachim von Loß (1576–1633) at Pillnitz Castle , who was passed down as the evil Loß and was married to Ursula von Schleinitz on Saathain . The privy councilor Christoph von Loss had a significant influence on the politics of the Saxon court under King Christian II.

By Bose (1664–1773)

From Reichspfennigmeister Joachim Christian von Bose, the inheritance passed to his son, Joachim Dietrich von Bose auf Schleinitz, Petzschwitz, Graupzig , Gödelitz , Seegeritz and Burkersdorf. Dietrich von Bose was a knight of the Order of St. John , electoral chamberlain and inspector of the prince school Sankt Afra in Meissen. Reports of so-called hunting camps from the years 1727 to 1736 have come down to us.

From Zehmen (1773–1906)

In 1773 Friedrich von Zehmen inherited the castle and manor Schleinitz at Stauchitz from his uncle, the Privy Councilor Carl Gottlob von Bose. Schleinitz Castle then formed a property complex with Petzschwitz, Gödelitz and Graupzig . Friedrich von Zehmen (1733-1812) visited the Franciscan Church in Meissen, studied law at the Alma Mater Lipsiensis and at the Salana in Jena. Eventually he became court and judicial councilor of the Electoral Saxony . After a year of drought in 1789 it came in 1790 to a poor harvest . In addition, there was the unequal legal situation of the peasants vis-à-vis the feudal hereditary courts, so that in 1790 the Saxon peasant uprising occurred in the Lommatzscher care . Landowner Friedrich von Zehmen noted that, with the judiciary now was over , as these of the subjects with beatings and violence being enforced. In his distress he had forty men ordered to Schleinitz from the artillery stationed in Lommatzsch . But on August 22, 1790, the farmers snatched the rifles from the soldiers, broke the saber of the commanding Lieutenant Bach and dragged the captured officer in their midst, armed with scythes, pitchforks and flails to Schleinitz Castle. There, the court administrator appointed by Zehmen, Kohl, was so abused that he died of the consequences on 23 August in Meißen . On the stone bridge of the castle, the landlord was forced to give a written waiver of all compulsory labor and grain interest. After the events of 1790 he sold the Schleinitz manor to his younger brother. The descendant Ludwig Gottfried von Zehmen-Schleinitz wrote several scientific reports on pomology . His son Hans-Dietrich vZ inherited the paternal estate Schleinitz etc., but lived mostly in London and died there on February 20, 1906. Since he had no children, his sister Marie Susanna von Zehmen, who was married to Dr. Heinrich Freiherr von Friesen the goods, u. a. Schleinitz.

By Friesen (1906–1945)

In 1906, Dr. Heinrich Freiherr von Friesen-Rötha the castle. Of his three sons who went to the First World War in 1914, only baron Stephan von Friesen survived. His two brothers Hans-Dietrich and Georg Friesen were buried under the linden trees of the Wallgang. Stephan von Friesen fell on the Eastern Front in Russia , his son Georg Dietrich Freiherr von Friesen (* 1923) was seriously wounded in Ukraine in 1944, but survived. His mother, the widow Marie-Josephe von Friesen, was the last bourgeois owner of Schleinitz Castle until 1945. Due to a warning from the Mayor of Meissen, the family managed to flee from the threatened deportation of the Soviets to Siebeneichen near Meissen. Thereafter, Georg's sister managed to return Marie-Luise Sahrer von Sahr von Schönberg to Schleinitz in October and watch how the castle was plundered by the Russians. The Dresden cultural assets stored in the castle during the war, including " dragoon vases " (see porcelain collection ), were, however, misused in the village for pickling cucumbers, and all of them were destroyed. Only one of them was rescued in a badly damaged condition, reconstructed and can be seen today in Moritzburg Castle . The mother fled from Siebeneichen on a coal train to Haidenburg , her children came later.

After 1945

After the war, displaced persons were quartered in the castle and an LPG was established. From the 1960s onwards, the von Friesen family kept in contact with those who remained in their homeland, often visited them, but always had to face state reprisals due to the fact that they were expelled from the district. The owners only received forty paintings and two cupboards from the entire property. There was no complete return of the stolen property or redress for the injustice.

In 1990 the LPG dissolved and the ruined castle stood empty. That is why on February 13, 1992, a Förderverein Schloß Schleinitz e. V. As start-up capital, the association received 200,000 DM from the Munich Dussmann Foundation . The association began to renovate the castle step by step and received further EU funding from the Leader II funding program and set up a culture, education and meeting center for the Lommatzscher care. In 1998 a restaurant GmbH was founded with 50,000 DM share capital to operate a three-star hotel with 19 hotel beds and 60 catering spaces. The castle chapel was used for weddings and a bridal suite was set up. Schleinitz Castle is operated by the Langer / Heilsberg family. It is also available for seminars, wedding and family celebrations as well as other events.

literature

- Otto Eduard Schmidt: The Lommatzscher care and the gender of those von Schleinitz. In: Saxon forays. Third volume. From the old Mark Meissen. Wilhelm Grunow, Leipzig 1906, p. 77ff.

- Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. Official governor creates Meißen-Land. Forty-first issue, Meinhold and Sons, Dresden, September 1923, p. 462ff.

- Schleinitz. In: Walter Schlesinger (Hrsg.): Handbook of the historical sites of Germany . Volume 8: Saxony (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 312). Kröner, Stuttgart 1965, DNB 456882952 , p. 319.

- Jan Peters , editor Barbara Krug-Richter, Martina Schattkowsky: Conflict and control in manorial societies, on resistance and domination behavior in rural social structures of the early modern period , publications by the Max Planck Institute for History, Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht Verlag, Göttingen 1995, ISBN 3 -525-35434-7 , essay by Martina Schattkowsky: ... and I want to live with you in peace and quiet. Background to the understanding of rulership by aristocratic manor owners in Electoral Saxony around 1600, pp. 359–403. Abraham von Schleinitz, Landadel in Kursachsen, the manor Schleinitz, Christoph von Loß are illuminated and a conclusion follows.

- Agnes and Henning v. Kopp-Colomb: Book of Fate II of the Saxon-Thuringian nobility. 1945 to 1989 and from the fall of the Berlin Wall until 2005. From the German Aristocracy Archive nF, Volume 6, CA Starke Verlag, Limburg an der Lahn 2005, ISBN 3-7980-0606-7 , p. 209 Freiherren v. Friesen auf Schleinitz, pp. 210–213 Georg-Dietrich Freiherr v. Friesen reports on the end of the war in 1945, pp. 213–216 Marie-Louise Sahrer v. Sahr v. Schönberg, b. Freiin v. Friesen adds to her brother's report.

- Martina Schattkowsky : With the means of the law. Studies on conflict resolution in a Saxon manor. Tel Aviv Yearbook for German History, Volume XXII, On the Social and Conceptual History of the Middle Ages, Tel Aviv University, Bleicher Verlag, Gerlingen 1993, ISBN 3-88350-496-3 , pp. 293-311. Explanations of the peasant uprising in 1790 as well as the development and disputes in Schleinitz legal practice ( patrimonial jurisdiction , appeal court in Electoral Saxony ).

- Martina Schattkowsky: Between manor, residence and empire. The world of the electoral Saxon nobleman Christoph von Loß auf Schleinitz (1564-1620) , Leipziger Universitätsverlag GmbH, Leipzig 2007, ISBN 978-3-936522-81-5 . Socialization processes between the manor and the Dresden court using the example of Schleinitz, explanations of aristocratic worlds and the creative power of Saxon Reichspfennigmeister.

- GA Poenicke (ed.): Album of the manors and castles in the kingdom of Saxony. Re-recorded after nature by F. Heise, Architect. Section II: Meissen Circle. Leipzig 1860, Schleinitz Manor, pp. 89–90

Web links

- Information on the Friends of Schloß Schleinitz e. V. , in 1994 the Friends of Schleinitz Castle was founded, which, in cooperation with the community, is the initiator of the maintenance and renovation of the ensemble.

- Information on the Schleinitz manor on ISGV / Digital Historical Directory of Saxony

- Information about the moated castle and Schleinitz Castle at Sachsens-Schlösser.de

- von Zehmen-Schleinitz: The importance of fruit growing from an economic and social point of view , Pomona. General German magazine for the entire fruit u. Weinbau als Zentralblatt der Pomologie , pp. 27–30, ninth year, editor Friedrich Jakob Dochnahl, Verlag Wilhelm Schmid, Nuremberg 1860.

- von Zehmen-Schleinitz: Something about the fruit tree culture of Saxony , article, published in Der Progress , 1858, p. 33.

- von Zehmen-Schleinitz: News about some types of fruit that were built in Saxony more than 200 years ago , article, published in Der Progress , 1859, p. 186.

- Hermann Schmidt: Sachsens Kirchen-Galerie , first volume, inspections Dresden, Meißen and St. Afra, parts 1–37, Dresden 1837, many explanations and mentions by Schleinitz.

- Gottfried von Zehmen: The correct planting of fruit trees / with special consideration of cultivation on a large scale, as a branch of agriculture , digital collections / Saxon State Library - State and University Library Dresden, history of technology, article, 1840, p. 11.

- Gottfried von Zehmen: The types of fruit that are also suitable for rough and cold locations / a lecture , Cooperative Flora, Verlag Liebsch and Reichardt, Dresden 1870. ZwB Forstwissenschaft - Magazin.

- Saxon Main State Archive Dresden: Holdings of the Schleinitz estate

- Bernhard Fabian: Libraries in Saxony , Olms New Media, Hildesheim 2003. Education and entertainment libraries of the landed aristocracy. For example in Schleinitz the book collection founded by Joachim Dietrich von Bose (1680–1742) and the Herrschaftlich von Zehmen'sche Bibliothek (Fideikommiss) the collection of approx. 4000 volumes.

- Robert Schmidt: Wanderwelt - Central Saxony. A summer morning in Schleinitz. Experience report 2010.

- Weller Panitz: Hiking and cycling tours in Saxony for the whole family , 2015, hiking route Stauchitz - Baderitz reservoir - Schleinitz Castle - Lommatzsch - Stauchitz, 45 km.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. Official governor creates Meißen-Land. Forty-first Issue, Meinhold and Sons, Dresden, September 1923, p. 462.

- ↑ a b Hermann Schmidt: Saxony's Church Gallery. First volume. Inspections: Dresden, Meissen and St. Afra. Dresden, September 1836, p. 108.

- ^ A b c Otto Eduard Schmidt: The Lommatzscher care and the sex of those von Schleinitz. In: Saxon forays. Third volume. From the old Mark Meissen. Wilhelm Grunow, Leipzig 1906, p. 77ff.

- ↑ a b Otto Eduard Schmidt: Manor of the Lommatzscher care. In: Messages from the Saxon Homeland Security Association. Dresden 1932, issue 1–3, volume 21, p. 57ff.

- ↑ a b c Karin Kolb: Cranach and Dresden. The works of Cranach in the Dresden picture gallery. Dissertation, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, ISBN 3-86624-011-2 .

- ↑ a b c Agnes and Henning v. Kopp-Colomb: Book of Fate II of the Saxon-Thuringian nobility. Starke Verlag, Limburg an der Lahn 2005, ISBN 3-7980-0606-7 , p. 209ff.

- ^ Martina Schattkowsky: Between manor, residence and empire. The world of the electoral Saxon nobleman Christoph von Loß auf Schleinitz (1574–1620). Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig, Leipzig, ISBN 978-3-936522-81-5 , p. 81ff. ( online ), accessed June 17, 2011.

- ↑ Sächsisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden (HStA): Document number 550 from January 28, 1255 , Bishop Konrad von Meißen confirms the purchase of the tithe in Burgwart Mochowe to the Altzella monastery.

- ↑ no information: Lommatzscher care. When Christoph von Loß ruled Schleinitz. Sächsische Zeitung, Meißen, November 14, 2007, p. 17.

- ^ Hanns-Moritz von Zehmen: Genealogical news about the Meißnian nobility of Zehmen, 1206 to 1906 . Wilhelm Baensch, Dresden 1906, p. 105f.

- ↑ Carl Christoph von Zehmen: Report on the peasant unrest in Schleinitz in 1790 , eyewitness report, article and interpreted by Christian Alschner, Meissner Heimat, 1959, pp. 9-14.

- ^ Henry Lehmann: Peasant uprising in the Meißner Land, 220 years ago. Leipziger Volkszeitung, Dresden Latest News, Dresden, December 13, 2010, p. 18.

- ↑ Reiner Gross: History of Saxony , special edition of the Saxon State Center for Civic Education, 4th expanded and updated edition, Dresden / Leipzig 2007, p. 177f.

- ↑ von Zehmen-Schleinitz: Something about the fruit tree culture of Saxony , essay, published in Der Progress , 1858, p. 33.

- ^ Hanns-Moritz von Zehmen: Genealogical news about the Meißnian nobility of Zehmen, 1206 to 1906 . Wilhelm Baensch, Dresden 1906, pp. 123 and 130

- ↑ Max Seydewitz: The invincible city. Destruction and reconstruction of Dresden. Kongress Verlag, Dresden 1956, p. 374.

- ^ Constanze Paffrath: power and property. The expropriations 1945–1949 in the process of German reunification. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-412-18103-X .

- ^ Heinz Flegel: Headquarters in Lommatzscher care. Out and about in the Jahnatal. In the footsteps of the von Schleinitz family, part II. Sächsische Zeitung, Meißen, June 4, 1998, p. 12.

- ↑ Dr. Vladimir Hajduch: Employing up to ten people in the palace ensemble at the end of 2000. Sächsische Zeitung, Meißen, June 2, 1999, p. 9.

- ↑ no information: EU funds construction at Schleinitz Castle. Sächsische Zeitung, Meißen, November 22, 1997, p. 9.

- ↑ no information: Three sparkling stars for Schleinitz Castle. Sächsische Zeitung, Meißen, April 4, 2001, p. 7.

- ↑ Jörg Mosch: Don't drive through, stop. Sächsische Zeitung, Meißen, November 13, 1999, p. 7.

- ↑ http://event-schloss-schleinitz.de/

Coordinates: 51 ° 9 ′ 48.1 ″ N , 13 ° 16 ′ 21.4 ″ E