Tartares lituaniens de la Garde impériale

|

Tartares lituaniens de la Garde impériale |

|

|---|---|

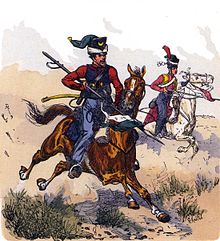

Officer and soldier of the Tartares lituaniens (watercolor by Bronisław Gembarzewski , 1897) |

|

| active | 1812 to 1814 |

| Country |

|

| Armed forces |

|

| Armed forces |

|

| Branch of service | Light cavalry |

| Type | Squadron |

| Strength | 123 |

| Insinuation | Guard impériale |

| Nickname | Cosaques de Poniatowski |

| commander | |

| Important commanders |

Mustapha Achmatowicz (1812) |

The Tartares lituaniens de la Garde impériale (German: Lithuanian Tartars of the Imperial Guard) consisted of soldiers of the Islamic faith of the Guard impériale . The unit was set up by decree by Emperor Napoléon in 1812. They were descendants of Crimean Tatars who had settled in the Baltic States . The squadron , which had its own imam , was set up at the beginning of the Russian campaign in 1812 , and the chief d'escadron Achmatowicz became the commander . After his death in Vilnius , the Capitaine Ulan took over the leadership of this short-lived unit, which was still used in the campaign of 1813 in Germany and 1814 in France. After Napoléon's abdication and the Restoration , the unit was dissolved.

Of little effectiveness, Tartar horsemen fought yet together with the prestigious one he régiment de chevau-légers polonais lanciers de la Garde impériale which they were allocated. There were many green elements in the uniform, an important color for Muslims. The headgear showed a copper crescent moon on the front, surrounded by three or four copper stars.

Origin of the Lithuanian Tartars

Colloquially called Tartars in the 17th and 18th centuries , they are now known as Tatars. In the 14th century, a number of these Tartars, who lived in Crimea, were recruited by the Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytautas as guards for his moated Trakai castle . After the unification of the Kingdom of Poland with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1385, the Tartars formed communities and settled in various villages.

Unlike the Lithuanian population, the Tartars were Muslim. They had religious freedom and were exempt from taxes, but had to do military service. After the division of Poland between the Tsarist Empire , the Kingdom of Prussia and Austria-Hungary in the XVIII. In the 19th century, the Tartars were incorporated into the Russian army. Volunteers served in the Polish army of the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807 .

organization

In June 1812, General Michel Sokolnicki was able to convince Emperor Napoléon of the need to set up a Lithuanian Tartar regiment. He argued:

"... your honesty and your courage are proven ..."

Thereupon the major Mustapha Murza Achmatowicz was charged with the formation of the Lithuanian regiment . Napoléon ordered the recruitment of 1,000 men, but the general enthusiasm was not as great as he had hoped, Achmatowicz could not bring together more than one squadron . It was 123 men strong and consisted of:

- a chef d'escadron

- a major

- a captain

- seven lieutenants and sous-lieutenants

- 106 NCOs and horsemen

The list took place officially in October 1812 with the assignment to the "1 er régiment de chevau-légers lanciers polonais". Achmatowicz paid for the uniforms and equipment out of his own pocket. Because of the Islamic denomination the unit was assigned an imam by the name of Aslan Aley. He also performed the duties of a "lieutenant en second".

Campaigns

During the Russian campaign , the Tartars belonged to the 6th Brigade of the Guard Cavalry, together with their regular regiment and the Gendarmerie d'élite de la Garde impériale . The squadron suffered losses, mainly from December 10th to December 12th in the chaos of Vilnius , where the chief d'escadron Achmatowicz was killed. She then fought on February 13, 1813 in the defense of Kalisz . At the end of the campaign, the casualties amounted to 100 officers and soldiers killed and missing.

The Capitaine Samuel Murza Ulan took command of the remaining 30 men in Posen . They were merged with the survivors of the regiment of the Lanciers lituaniens de la Garde impériale , which had been completely wiped out by the Russians near Slonim in October 1812 - but this did not last due to difficulties caused by aversions . The Capitaine Ulan then received permission to separate from the regiment with his troops. The Tartars were then still 35 riders in 15th company to the one he régiment de chevau-légers polonais lanciers de la Garde allocated. This regiment was awarded the title of Middle Guard. In addition to the Capitaine Ulan, Lieutenants Ibrahim and Aslan Aley were also on duty.

From April to June 1813, the Capitaine Ulan tried to win new recruits for his unit, and for this purpose went to France with the Maréchal des logis boss Samuel Januszerwski. At that time the unit consisted of only 47 riders. In Metz they had wanted to assign him non-Muslim soldiers as replacements, which he refused. He then came to Paris with six new recruits, where he wanted to present the situation to the Minister of War, Henri Clarke d'Hunebourg . Without result, he left Paris with 24 recruits and arrived in Friedberg (Hesse) , where the "Chevau-légers lanciers polonais de la Garde" depot was located.

In August the handful of soldiers the captain had brought with him were incorporated into the small company before hostilities resumed. The Tartars fought alongside the Polish Uhlans during the campaign in Germany in the Battle of Dresden , the Battle of Peterswalde (Mecklenburg), the Battle of Leipzig and the Battle of Hanau . In December the workforce was 46 riders, 23 of which were not operational. They then took part in the campaign in France, in which they lost another 13 dead and six horsemen were taken prisoner. After Napoleon's abdication, the surviving men returned to their homeland.

Uniformity

The Lithuanian Tartars had a uniform similar to that of the Cossacks. There were variations in the formation of the unit depending on the tribes from which the recruits came. The only thing they had in common was the cap's green pouch, an important color in the Muslim religion (including that of the Prophet Mohammed). A crescent moon and stars, elements related to Islam, appeared on the cap. When the unit was incorporated into the Polish Uhlans of the Guard, General Krasiński gave them a more uniform uniform, but the diversity lasted until 1814 when their equipment was completely renewed. The development of clothing can be found in two periods: 1812 and then from 1813 to 1814. The exact details of the officers' uniform can no longer be traced.

Headgear

The headgear consisted of a hat made from the fur of the Karakul sheep with a patent leather peak and a green hat bag with a red tassel. There was a copper crescent moon at the front, surrounded by three or four copper stars. A yellow turban was wrapped around the lower edge . In 1813 this hat was replaced by a Kolpak . The turban, the crescent moon, and the stars were now gone. A white lanyard with two raquettes was attached to the cap . (The raquettes consisted of a plaited circle of white or colored thread to which acorns were attached.) A red plume was attached to the tip of the Kolpak, the cap bag had no passepoils . The cap was held under the chin by a brass scale chain.

According to the description from the Marckolsheim manuscript, in 1812 the trumpeters wore a black Kolpak without a turban with a white catch cord and a white plume. The hat pouch was green with yellow passepoils and a red tassel. The baton trumpeter's Kolpak (brigadier trompette) was white with a copper crescent on the front and a blue, yellow-striped turban at the bottom. The hat bag was blue with yellow passepoils and a red tassel at the top. There was also a white and red plume of feathers.

dress

A scarlet supra vest was worn over the green jacket , which was bordered by a double row of yellow piping. The scarf behind the stand-up collar of the vest was red with yellow piping. The flaps of the epaulettes were yellow, as were the buttons. In the work Les uniformologues by Liliane and Fred Funcken, the uniform is shown without lace trim on the sleeves, in contrast to Emir Bukhari, who indicates a red trim with yellow piping.

A yellow cloth belt was looped around the waist, which could be replaced by a gold-interwoven white belt. The coat was like that of the Mamelouks de la Garde impériale . The wide trousers (charroual) were green, decorated with crimson lampasses . The boots were black. In 1813 the green jacket turned scarlet and the red supra vest turned yellow with black piping. The color of the pants changed from green to indigo.

In 1812 the trumpeters wore a yellow jacket, over it a red vest with yellow trimmings. The red cuffs on the sleeves were designed in the shape of a clover, the trousers crimson with green and yellow stripes. The trumpeter's uniform was blue with a red cloak with yellow buttons and cuffs of the same color on the sleeves. The vest was red with yellow stripes. The trousers were blue with red and yellow braids and decorated with Vitéz Kötés made of crimson thread. The boots were yellow.

Armament and equipment

The main armament was a 2.75 meter long lance . It had a pennant - red above, white or green below. A dagger was housed at an angle in the belt . There was also a saber of the same model as that used by the Lanciers de la Garde . The scabbard was made of copper. There is no information about the firearms used. Personal equipment included a black canteen decorated with a copper eagle. The bandolier and saber belt were made of white leather. The saddle lay on a red saddlecloth with a yellow border, the rear corners of which were decorated with a yellow, crowned eagle. There was also a coat bag of red color with a yellow border.

literature

- Jean Brunon: Des Tatars au service de Napoléon: sur un projet de soulèvement des Cosaques et des Tartares au profit des Armées françaises et aperçu historique sur l'escadron de Tartares lithuaniens de la Garde impériale, 1812–1814. Raoul et Jean Brunon, Marseille 1938, 10 pp.

- Didier Davin: Des Tartares pour l'Empéreur ou le destin tragique des Tartares lithuaniens (1812-1814). In: Figurines. No. 93, April 2011.

- Philip Haythornthwaite (alias Richard Hook): La Garde impériale ( Armées et batailles. No. 1). Del Prado & Osprey Publishing, 2004, 63 pages, ISBN 2-84349-178-9 .

- Alain Pigeard: Les tartares lithuaniens. In: Tradition Magazine. No. 8 (hors-série): Napoléon et les troupes polonaises 1797–1815. De l'Armée d'Italie à la Grande Armée. January 1, 1999.

- Jean Tranié, Juan-Carlos Carmigniani: Les Polonais de Napoléon. L'épopée du 1 er régiment de lanciers de la garde impériale. Copernic, 1982, 179 pp.

- Emir Bukhari: Napoleon's Guard Cavalry. In: Men-at-Arms. No. 83, 1978, ISBN 0-85045-288-0 .

Footnotes and individual references

Footnotes

- ↑ Tartars instead of Tatars was the name used

- ↑ Major was not a rank, but the job title for the chief of regimental administration

- ↑ There are different spellings: "Assan Alay" after Pigeard; "Assan Alny" after Hourtoulle

- ↑ Second class lieutenant, in Germany it can be compared with sergeant major

- ↑ depending on the sources

- ↑ round or oval braids, removed like a tennis racket

Individual evidence

- ↑ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 13

- ^ Gilles Dutertre: Les Français dans l'histoire de la Lituanie (1009–2009). L'Harmattan, 2009, ISBN 978-2-296-07852-9

- ↑ a b c Davin 2011, p. 26

- ↑ Pigeard 1999, p. 29

- ↑ Bukhari 1978, p. 27

- ↑ Brunon 1938, p. 4

- ↑ Alain Pigeard: La Garde impériale 1804-1815. Tallandier, 2005, ISBN 978-2-84734-177-5

- ↑ Brunon 1938, p. 5

- ↑ Tranié / Carmigniani 1982, p. 97

- ↑ Pigeard 1999, p. 30

- ↑ Brunon 1938, p. 6

- ↑ Pigeard 1999, pp. 30, 31 and 32

- ↑ a b Pigeard 1999, p. 32

- ↑ Tranié / Carmigniani 1982, p. 112

- ↑ a b c Bukhari 1978, p. 24

- ↑ Davin 2011, p. 27

- ↑ a b c d Liliane and Fred Funcken: L'uniforme et les armes des soldats du Premier Empire. De la garde impériale aux troupes alliées, suédoises, autrichiennes et russes. Volume 2. Casterman, 1969, ISBN 2-203-14306-1

- ↑ Bukhari 1978, pp. 24 and 29

- ↑ a b Roger Fort Hoffer: Le manuscrit de Marckolsheim. Roger Forthoffer, 1960 (new edition from 1820)

- ↑ Bukhari 1978, pp. 24 and 28

- ↑ Bukhari 1978, p. 28

- ↑ Bukhari 1978, pp. 28 and 29

- ↑ Bukhari 1978, p. 29

- ↑ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 52