1 he regiment de chevau-leggers lanciers polonais

|

1 he régiment de chevau-légers lanciers polonais de la Garde impériale |

|

|---|---|

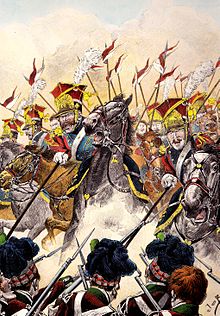

On the way to the parade |

|

| active | April 6, 1807 to October 1, 1815 |

| Country |

|

| Armed forces |

|

| Branch of service | Guard |

| Type | Light cavalry |

| Strength | 970-1700 |

| Insinuation | Guard impériale |

| Location | Chantilly |

| Nickname | "Lanciers polonais" |

| march | Marsz trębaczy (Trumpet March ) |

| commander | |

| commander | Last: Paweł Jerzmanowski (1815) |

| Important commanders |

Wincenty Krasiński (1807-1814) |

The 1 er régiment de chevau-légers lanciers polonais ( Polish 1 Pułk Szwoleżerów-Lansjerów Gwardii Cesarskiej ) was a unit of the light cavalry of the Guard impériale . Situated 1807 array of Kaiser Napoléon I he , the regiment served in the Grande Armée 1815. With until the end of the Empire a personnel strength of 1000 riders and 32 members of the rod it was the fourth cavalry regiment, which was set in the Imperial Guard.

The unit was able to earn notable merits in the Spanish War of Independence , when in the battle of Somosierra a single escadron of the Chevau-légers was able to conquer a well-entrenched Spanish artillery position with four batteries , although it was strongly protected and several thousand Spaniards were in the immediate vicinity. After this remarkable action, the regiment was accepted into the Old Guard . In 1809 it was the first cavalry regiment of the Guard to be equipped with the lance , which led to the additional designation "Lanciers polonais". They formed a brigade with the Dutch lancers rouges de la Garde impériale .

The regiment was able to distinguish itself in the Russian campaign in 1812 , where it was feared by the Cossacks and was able to protect Napoleon and his staff from an enemy attack in the battle near Gorodina . Only 437 horsemen were left after the withdrawal from Russia and the campaigns in Germany in 1813 and in France in 1814. After Napoleon's abdication , almost the entire corps returned to Poland. Only an escadron under the command of Paweł Jerzmanowski accompanied Napoléon to the island of Elba and then attacked during the reign of the Hundred Days in the battle of Waterloo at the head of the “Lanciers rouges”. On October 1, 1815, this Escadron was dissolved. This last foreign unit remained loyal to the emperor until the end of the epoch.

organization

La garde d'honneur polonaise (Polish Honor Guard)

The establishment of a Polish regiment within the Imperial Guard did not succeed until 1807, although the project had already been suggested by Wincenty Krasiński in 1804 . At that time he was in Paris, where he tried to contact Napoleon. At that time Poland was occupied by foreign powers, but efforts were already under way to regain independence. Many Poles in exile had joined the French revolutionary army.

However, one had to wait until 1806 for Poland's hopes for a renaissance to materialize. After the Prussian defeat in the battle of Jena and Auerstedt , Napoléon moved into Berlin and directed his further activities against the Russian army under General Bennigsen , which ultimately led to the Peace of Tilsit and the proclamation of the Duchy of Warsaw . On the initiative of Michał Kleofas Ogiński , an honor guard was then set up as an escort for the emperor. It was an extraordinarily sizeable troop made up of members of the most distinguished Polish aristocratic families. The emperor remarked:

"[...] offer a guarantee of high morality due to their upbringing."

The total strength was set at 480 riders, commanded by Colonel Krasiński. Some of the troops accompanied Napoléon on the next campaign and were present at the battle of Eylau . After their return, Napoléon incorporated these Chevau-légers into the Imperial Guard.

Line-up of the Chevau-leggers polonais de la Garde

On April 6, 1807 Napoléon issued a decree at Finckenstein Castle to set up a regiment “Chevau-légers polonais de la Garde impériale”. At the suggestion of Général Dombrowski, the former commander of the Polish Honor Guard, Wincenty Krasiński, was appointed regimental commander. Only members (between the ages of 18 and 40) of the Polish aristocratic families were envisaged, who could be described as wealthy, but this was not possible in reality, which is why the lower or impoverished nobility had to be taken into account. The soldiers theoretically had to pay for their equipment and uniform themselves, but the treasury offered a repayable advance, which was withheld at 25 cents a day from their wages.

The inexperience of the new troops prompted the emperor to integrate them into a powerful association and thus to assign them to the Imperial Guard. They received French instructors and medical officers, as well as two French deputy regimental commanders (Colonels en second), Antoine Charles Bernard Delaitre , a former member of the Mamelouks de la Garde impériale , and Pierre Dautancourt (also d'Autancourt ) from the Gendarmerie d'élite . His organizational talent and his successful training methods earned him the nickname “Papa” among his riders.

The maximum manpower of the regiment should theoretically be 1000 officers, NCOs and men, plus 32 staff members. The four escadrons were under the command of Andrzej Tomasz Łubieński, Jan Leon Kozietulski, Ferdynand Stokowski and Henryk Ignacy Kamieński. Each escadron consisted of two companies of 125 riders each, commanded by a captain . In practice, however, the regiment only had 968 riders. The unit was put together in the Mirowski district in Warsaw. On June 17, 1807, a first detachment of 125 riders under the command of Chef d'escadron Łubieński left Warsaw and rode to Königsberg (Prussia) , where they were received with applause. After the formation was completed, the rest of the regiment was commanded to Paris in October. The Poles were assigned the grandes écuries of Chantilly Castle as general depot .

A part of the Chevau-légers, together with the Grenadiers à cheval , the Chasseurs à cheval and the Dragons de la Garde , became a permanent part of the emperor's bodyguard.

development

When it was set up, the regiment had four escadrons of two companies each . In 1812 a fifth escadron was added, and in March 1813 a sixth. The first three escadrons belonged to the Old Guard , the other three to the Young Guard. In July 1813, the regiment was reinforced to seven escadrons, as the 3rd regiment of the former Lanciers lituaniens de la Garde impériale and the Tartares lituaniens de la Garde impériale (Lithuanian Tartars of the Imperial Guard) were incorporated. The first three escadrons stayed with the old guard, the fourth to sixth escadron switched to the middle guard and the seventh escadron was assigned to the young guard. In August the regiment was split up, the first three and part of the fourth Escadron formed the 1st regiment, the others the 2nd regiment. The division did not last long, in December the Uhlans had shrunk to four escadrons and were reunited in one regiment.

Campaigns

Spain (1808 to 1809)

- From Madrid to Burgos

Depending on the level of the organization, the Polish departments were assigned first to Chantilly and then to Spain in order to reinforce the French occupation forces there. During the uprising of May 2, 1808 ( Dos de Mayo ), a division of the Chevau-légers was in action in Madrid. The cavalry of Maréchal Murat rode through the streets and sabered the insurgents down (sabrait les insurgés) . They suffered several losses in the process, and Krasiński was wounded. The uprising expanded and spread to parts of the regular Spanish army. Then the Maréchal Bessières collected the divisions Lasalle , Merle and Mouton as well as parts of the Garde impériale from the garrison of Burgos. 91 Chevau-Legers were posted. The matter led to the Battle of Medina de Rioseco on July 14, 1808 . When a company of voltigeurs was smashed in front of the French lines, the Général Lasalle decided to intervene with the guard cavalry - dragoons , gendarmes d'élite and the "Chevau-légers polonais" - to restore the situation. In this attack, the Spanish Gardes du Corps and the regiment of the royal carabiniers were dispersed and put to flight.

"[...] the escadron of Capitaine Radziminski alone drove the regiment of the Queen Dragoons apart."

In this attack, the Chief d'escadron Louis Michel Pac and Lieutenant Szeptycky were wounded and two horses were killed.

At the end of July, the last two escadrons arrived in Spain, where they were combined with the existing ones to form an association and assigned to the cavalry division of Général Lasalle. From this they were assigned to outpost duties.

With the surrender of Général Dupont at the Battle of Bailén , the success in the Battle of Medina de Rioseco had been lost, Madrid had to be surrendered by the French, who withdrew behind the Ebro .

In November 1808, Napoléon entered Spain at the head of the Grande Armée to restore the status quo ante. The Chevau-légers from Krasiński were already there and cunningly seized the city of Medina de Rioseco , which then swore the oath of allegiance to King Joseph . At the same time, Emperor Napoléon commissioned the Maréchal Soult to destroy General Belveder's Spanish army and occupy Burgos. The Battle of Burgos on November 10th turned into a French success. Lasalle pursued the refugees and was able to capture a cannon and a war chest.

- The attack at Somosierra

Satisfied with the outcome of the Battle of Burgos and the Battle of Espinosa , Napoléon marched on Madrid. The main route of advance led past Somosierra , which was occupied by Spanish troops under General Benito de San Juan, who blocked the road here. To do this, they deployed four artillery batteries that were positioned along the road. In the evening, the 3rd Polish Escadron, which was ad interim under the command of Jan Leon Kozietulski, was deployed by Napoléon. Maréchal Victor's infantry had had to withdraw, and Napoléon grew impatient. Despite Colonel Piré's remark that an attack was impossible, he turned to Kozietulski and said to him:

«Enlevez-moi ça au galop. »

"Remove that for me at a gallop."

The approximately 150 riders of the 3rd Escadron had to take a path that was 2.5 kilometers long and had a height difference of 300 meters to attack. It was lined with stone walls and rows of poplar trees on both sides, which made the attack all the more difficult. The Escadron rode in a column of four because a broader development was not possible. Kozietulski gave the order to attack. The Spaniards opened fire, Lieutenant Rudowski was killed while his comrades reached the first battery, knocked down the guns and the attack continued. The Chef d'escadron Kozietulski lost his horse, the Lieutenant Krzyżanowski and a number of the Chevau-légers were killed.

Command passed to Captain Jan Dziewanowski, who was able to capture the second and third batteries. Due to the resulting losses, the last available officer, Lieutenant Andrzej Niegolewski, had to take command. He attacked the fourth battery with the few remaining riders, but could not do anything and had to withdraw. At that moment the Chasseurs à cheval de la Garde appeared , then the 1st, 2nd and 4th Escadron of the Polish Chevau-légers and behind them French infantry. A few minutes later the Spaniards fled.

November 30, 1808 brought heavy losses to the regiment. According to Niegolewski and Dautancourt, it had lost seven officers and 50 non-commissioned officers and men. Of these, three lieutenants had died, Capitaine Dziewanowski died of his wounds, Kozietulski, Niegolewski and Capitaine Krasiński were wounded. (In his bulletin of December 2, Napoléon admitted only eight fallen and 16 wounded.) The next day the Emperor in Buitrago awarded the Legion of Honor 16 times to the survivors and on this occasion accepted the regiment into the Old Guard .

«Vous êtes dignes de ma Vieille Garde. Honor aux braves des braves! »

“You are worthy of my old guard. Honor the bravest of the brave! "

The attack at Somosierra was the most spectacular action of the Polish cavalry in the Napoleonic Wars and the cheapest victory of the emperor.

The Polish horsemen then stood at the side of the "Chasseurs à cheval de la Garde" of Lefebvre-Desnouettes in pursuit of General John Moore's British troops , without taking part in the Battle of Benavente , in which the Chasseurs of the cavalry of Henry Paget , 1st Marquess of Anglesey , were defeated. An escadron under the command of Łubieński accompanied Napoléon back to France, the remnants of the regiment soon followed.

Campaign in Austria, takeover of the lance

The Chevau-légers returned to Paris on March 20, 1809 and took up quarters in the École militaire . The campaign against Austria began the following month, the riders left Paris department by department and made their way to Germany. In the battle of Aspern they were in Général Walther's division . On the left bank of the river in a fierce battle, they lost the Capitaine Kozycki and six horsemen to the dead, the Lieutenant Olszewski and 30 horsemen were wounded. By the evening of May 21st, the losses were heavy and the French were no longer in control of the action, resulting in defeat. Napoléon was not satisfied with this and began preparations for the next battle, the battle of Wagram . On July 4th the regiment had been brought to a number of 58 officers and 1,078 horsemen.

When the Austrian cavalry pressed the French infantry heavily during the battle and inflicted heavy losses on them, the Chevau-légers von Krasiński were used by Maréchal MacDonald . The regiment attacked the Uhlans from the Schwarzenberg regiment , which in turn consisted of Galician Poles. The Uhlans were put to flight after the Chevau-légers had received support from the Chasseurs à cheval of the Guard. 150 prisoners were made, including Prince Auersperg, and two cannons were captured. The own losses were just as heavy as at Somosierra, 26 killed and 80 wounded were the balance of the day.

After the battle, Colonel Krasiński asked for the Chevau-légers to be equipped with a lance . In Poland it is a very popular weapon that goes back to the Kopia of the Polish Hussaria . During a demonstration in Schönbrunn Palace , the Maréchal des logis Roman was able to throw two dragoons of the Imperial Guard from their horses with a lance . The emperor complied with the request and the Chevau-légers were given the suffix “Lanciers polonais” (Polish lancers).

Years of Peace (1810 to 1811)

After the Battle of Wagram, the regiment was housed in Schönbrunn Palace, and an escadron was assigned to the Kaiser as an escort. After the peace treaty of October 14, 1809, on December 2, it took part in the great parade on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of Napoleon's coronation on the Place du Carrousel . At the beginning of 1810, two escadrons under the command of the Capitaines Szeptycki and Tarczyński were posted to Spain, where they were assigned to the troops of Général Antoine Charles Bernard Delaitre . One escadron was subordinated to the 1st Infantry Division of the Imperial Guard under Général François Roguet and another Escadron to the 2nd Infantry Division of the Guard under Général Pierre Dumoustier . This troop left Paris with 315 riders on December 16 and reached the Spanish peninsula via Bayonne . The “Lanciers polonais” who stayed behind in France were used on ceremonial occasions and were also used at the wedding of Napoleon and Marie-Louise of Austria on April 1, 1810 and at the baptism of the heir to the throne Napoleon II on March 20, 1811.

About 400 horsemen accompanied the emperor and his wife on a trip to Belgium and Napoléon on an inspection of the maritime provinces.

Colonel Wincenty Krasiński was promoted to Général de brigade and made Count of Opinogóra . A large number of the regiment's officers and riders were promoted for their merits in past battles.

During this time the riders were trained in the use of the lance as they were very inexperienced in this field. For this reason, the emperor often had demonstrations and parades held in the Palais des Tuileries to see for himself the progress of the training. After the annexation of Holland, the members of the guard cavalry of King Louis Bonaparte became the 2nd e régiment de chevau-légers lanciers de la Garde impériale , the "Lanciers polonais" had therefore become the "1 er regiment".

In April 1811 the Légion de la Vistule (Weichsellegion) was set up, and around 100 men of the regiment were given up to form the cavalry division - including Andrzej Tomasz Łubieński, who rose to become colonel in the new unit.

The regiment of the "Lanciers polonais" had been reinforced by March 1812 so much that a fifth Escadron was set up. The command was given to Paweł Jerzmanowski.

Back at war: campaign in Russia

March to Moscow

When the war between France and Russia broke out in 1812 , the Grande Armée began their march on Moscow on June 23, by crossing the Nyemen .

The next day the “Lanciers polonais” crossed the Neris and followed the general march on Vilna . Since most of the Polish riders knew the Russian language, they were often used for enlightenment purposes. The regiment was also often given courier duties. On July 27, the remaining Russian cavalry detachments in Vitebsk were driven out of the city by Paweł Jerzmanowski's “Lanciers polonais”, which resulted in losses of around twenty men. The regiment then stayed in town until August 13th.

On August 14th, the "Lanciers polonais" formed a brigade with the regiment of the Lanciers rouges de la Garde impériale , which was commanded by Général Colbert-Chabanais . The corps arrived in Krasny on August 15, but did not stay there, but moved on to the Dniepr to investigate possible crossings. On this way they met the Russian rearguard, which was initially driven back by the 1st regiment under Krasiński and Dautancourt, but which then had to break off the pursuit before the massive fire of the Russian infantry and cannons on the other side of the river. The "Lanciers rouges" of the 2nd regiment under Montbrun came to reinforce, but nothing could be done against the Russians, who were returning under the protection of their artillery.

On the way to the battle for Smolensk , the "Lanciers polonais" clashed with Cossacks who repeatedly attacked the French columns. The regiment marched on towards Moscow and arrived in Vyazma in late August . It consisted of 955 riders, 455 of whom were assigned to Napoléon and 125 to Murat . The rest were in the depots or were on their way with orders. After helping to fortify the Chevardino field on September 5, the Poles went to the Battle of the Moskva four days later. Here, however, the Colbert Brigade was not used and had to be content with the role of the spectator. On September 15, a 70-man division of the “Lanciers rouges” was ambushed on a reconnaissance ride near Borovsk and was freed from it by an escadron from the “Lanciers polonais”. The losses amounted to 12 men. On September 18 or 19 the regiment arrived in front of Moscow.

«Nous découvrîmes bientôt cette capitale que d'immenses colonnes de feu et des tourbillons de flammes et de fumées dérobaient en partie à notre regard. »

"Soon we discovered this capital, which was partially hidden from our eyes by huge columns of fire and whirlwinds of flames and smoke."

When the emperor left the Kremlin , six lancers from the Escadron on duty covered him with their cloaks against the embers and ashes. The regiment then bivouacked in the suburb of Troitzkoe, tending the horses and getting the equipment in order.

On September 21, 1812, by order of Napoléon, the brigade left Moscow and joined forces with Maréchal Murat to pursue the Russians. After a four-day march, the brigade reached the village of Vladimirskiy Tupik, where the vanguard from an escadron of the "Lanciers rouges" under Capitaine Calkoen was in distress due to a sudden attack by the Cossacks. It was only thanks to the rapid intervention of an escadron of the Polish regiment under Capitaine Brocki that the Dutch were not destroyed. The Cossacks were forced to retreat and took Capitaine Brocki as a prisoner. The two regiments crossed the Desna , reached Gorky Leninsky, and arrived in Voronovo on October 5th.

Withdrawal from Russia

Napoléon ignored Tsar Alexander I's offer of peace , but gave the order to withdraw from Moscow on October 19. The "1 er lanciers" belonged to the vanguard and had the task of securing the crossings over the Desna.

During the retreat, the Cossacks avoided as much as possible attacking the “Lanciers polonais”, who suffered from the cold, and preferred to stick to the Dutch “Lanciers rouges”, even if the Poles were not entirely spared. During the battle at Gorodnia, Napoleon decided to conduct a reconnaissance with his staff, and was surprised by a division of Cossacks. The Poles under Kozietulski intervened immediately, and with the help of the Chasseurs de la Garde , then the Dragons and the Grenadiers à cheval , the situation was resolved. The regiment lost six men in this operation. Some Cossacks were captured during the battle of Krasnoye . The own losses amounted to 38 riders. On November 27, the regiment crossed the Berezina and lost another 49 men in the battle of the Berezina . On December 5, 78 Chevau-légers arrived in Smorgoni as reinforcements . The imperial escort under Colonel Stokowski, reinforced by parts of the 7 e régiment de chasseurs à cheval , had lost two thirds of their staff after their arrival in Smarhon . The remnants of the regiment accompanied the imperial treasury and arrived in Vilnius on December 9th . At the beginning of the campaign the regiment consisted of 1,108 riders, at the end of which there were 437 men and 257 horses left.

During the entire campaign, the “Lanciers polonais” were the only ones who were really feared by the Cossacks because of their skill in handling the lance.

Campaign in Germany

First phase, January to May 1813

At the beginning of 1813 the remnants of the regiment were on Polish territory. The determined strength was 437 men and 257 horses, plus an undisclosed number of soldiers in the depot in Warsaw . The unit was then brought back to war strength by integrating the remnants of the Lanciers lituaniens de la Garde impériale on March 22, 1813 and subordinate the company of the Tartares lituaniens de la Garde impériale under Capitaine Ulan to the regiment. In addition, the "Gendarmes lituaniens" (Lithuanian gendarmerie) came as reinforcements, which brought the regiment back to a strength of 13 companies. When another replacement arrived with 500 mounted riflemen from the Dombrowski division, the unit was soon operational again. The staff now amounted to 1500 riders. Because many of the horses of the Grande Armée had been lost in Russia, Napoléon was forced to make greater use of the cavalry of his guards in the following campaign. On May 1, the Maréchal Bessières , who was accompanied by an escadron of the regiment on a reconnaissance ride, was killed by a cannonball near Rippach . In the battle of Lützen , four escadrons of the regiment were decimated by Prussian artillery fire without actively intervening in the action.

«[…] On serrait les rangs lorsque les hommes et les chevaux tombaient. »

"[...] we closed the ranks while men and horses fell."

The mere presence of the “Lanciers polonais”, however, caused the enemy to concentrate more forces here, thereby enabling the Young Guard to carry out a successful counterattack.

This victory opened the way to Dresden for the French . The “Lanciers polonais” received an additional escadron as reinforcement. During the battle of Bautzen the regiment was in reserve. On the morning of May 22nd, the Guards Cavalry, under the command of Général Walther, and the 1st Cavalry Corps of Général Latour-Maubourg were tasked with pursuing the defeated enemy. In the battle of Reichenbach and Markersdorf they clashed with the troops of Eugen von Württemberg between Reichenbach in the west and Markersdorf in the east, about 12 km west of Görlitz. The "Lanciers polonais" were directed to the wooded heights behind the town.

«[...] fair demi-tour à gauche et nous jeter sur le flanc de l'ennemi pour l'obliger à se retirer. »

"[...] made a U-turn to the left and threw us on the flank of the enemy to force him to retreat"

The two escadrons from Chłapowski, followed by two others under Jerzmanowski, were initially able to operate successfully against the Russian cavalry. The Poles attacked the rearguard of the Russians, but were repulsed by the Russian artillery with losses. At that moment the Chasseurs à cheval de la Garde and the Mamelouks de la Garde appeared to reinforce them. The Saxon cuirassiers also moved forward, but soon after massive artillery fire had to retreat and be replaced by the Poles. The Russians gradually withdrew and left the battlefield to the French.

Second phase, June to December 1813

Peace was soon made between the French and the Allies. The Poles were stationed in Dresden. In the short period of peace they were able to recover, but were also used to fight partisans. In June 1813 a seventh Escadron was set up, which brought the regiment to a staff of 1750 riders. The regiment was divided into three groups: the first three escadrons belonged to the Old Guard, the fourth, fifth and sixth Escadron to the Middle Guard, and the seventh Escadron to the Young Guard.

The war soon started again, and this time the Austrians joined the coalition against Napoleon. Although outnumbered in the Battle of Dresden , the French managed to win a victory. The guard was able to distinguish itself, an escadron under Jerzmanowski was able to capture an entire Prussian battalion, Lieutenant Hempel brought in 300 prisoners with 40 men. On September 16, 1813, the 1st and 2nd Escadron (assigned to a platoon of 25 horsemen of the 4 e régiment de gardes d'honneur ) under the command of Chef d'escadron Séverin Fredro led the battle near Peterswalde against five escadrons of the 1st Silesian hussar regiment under the command of Colonel Franz von Blücher , son of Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher . They were supported by infantry and two cannons. The Lancers attacked the hussars and drove them to flight. These left Colonel Blücher and 20 horsemen in the hands of the French. The Emperor immediately decorated the Chef d'escadron Jankowski with the Order of the Legion of Honor. One month later, in the Battle of Leipzig , on the afternoon of October 16, the Austrian cuirassier regiment Somariva came threateningly close to the imperial staff. It could be pushed aside by an attack by the French guard cavalry, including the "Lanciers polonais". On October 19th the battle was lost and the French army retreated. During the retreat, the commander of the rearguard, Maréchal Poniatowski , drowned when, wounded several times, tried to swim across the White Elster on horseback. The members of the army were deeply depressed, and the guards were not spared, which had never happened in the history of the regiment, around 50 men had to be recorded as deserters. The Poles wanted to go home now to help shape their country. However, she was able to deliver a personal address by Napoléon on October 25 in the ranks of the Grande Armée. The campaign of 1813 ended with the Battle of Hanau on October 30th. Here the Chevau-légers clashed with Bayern several times and suffered heavy losses. They were led by Jerzmanowski and Dautancourt, who were both rewarded at the end of the battle; one with the cross of the Legion of Honor and the other with the promotion to the Général de brigade .

In December, the "3 e régiment des éclaireurs de la Garde impériale" was assigned to the "Lanciers polonais", which was now called "Éclaireurs-lanciers". Commanders were Krasiński and Dautancourt. At the same time the regiment was reorganized into four escadrons of two companies each.

Campaign in France

The campaign in France began in November 1814. Under the command of Général Krasiński, the Poles were able to distinguish themselves in all battles during the campaign. In the Battle of Brienne the Poles and the Chasseurs à cheval von Lefebvre-Desnouettes invaded the city and tried in vain to capture Field Marshal Blücher . A few days later they faced the Allied army at the Battle of La Rothière . The “Lanciers polonais” initially held the von Lanskoy cavalry in check and then withdrew from the von Wassilichikow. The disproportionate forces initially forced the French to retreat; Napoléon then went back on the offensive and defeated General Olsoufiev in the Battle of Champaubert on February 10th.

The Poles, who arrived too late on the battlefield, fought the following day in the Battle of Montmirail , where they, together with the Chasseurs à cheval de la Garde, attacked Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg's Prussian infantry and forced them to retreat. In the battle of Vauchamps , the Krasiński lancers attacked the infantry of Hans Ernst Karl von Zieten's corps and were able to drive them apart with the help of the Grouchy cuirassiers . This was followed by participation in the Battle of Mormant on February 17 and the Battle of Montereau on February 18. Eugen von Württemberg wanted to secure the crossing over the Seine and divided up a troop for this. After the French attempts to evict the security troops failed, Napoléon ordered the cavalry under Général Pierre Claude Pajol to retake the bridge. Pajol obeyed and drove the enemy out, while at the same time the escadrons of the Guard, including Jerzmanowski's Poles, fought by his side and participated in the pursuit. A Polish escadron surprised a Prussian detachment near Rocourt and captured their bivouac. At that time reinforcements arrived from Chantilly under the command of Général Louis Michel Pac .

The surrender of Soissons to the Blücher corps saved the city from destruction. Napoleon was upset by this and decided to continue his attacks. On March 5, he ordered Étienne Marie Antoine Champion de Nansouty to take the bridge at Berry-au-Bac . Ferdinand von Wintzingerode's Cossacks were driven out by the Poles under Général Pac and the chief d'escadron Skarżyński, the bridge was crossed, and the scattered Russians who were trying to regroup were dispersed again, the equipment, supplies and two cannons captured , made 200 prisoners. The French crossed the Aisne and two days later stood in the battle of Craonne . The Chevau-légers of Dautancourt attacked the Ferme d'Hurtebise with the shiny saber and chased the Russian cavalry of the rearguard to flight. The defeat in the Battle of Laon initially forced Napoléon to retreat, but he successfully took the initiative again in the Battle of Reims against the Russians under Saint-Priest .

The "3 e régiment de gardes d'honneur" of Colonel Belmont-Briançon encountered stubborn resistance, and it was only thanks to the intervention of the "Lanciers polonais" and the artillery of Drouot that control of the city was obtained. The Poles, under Krasiński's command, crossed the Saint-Brice bridge and destroyed a Prussian column that was in retreat. They took 1,600 prisoners and captured three cannons along with the baggage .

In the lost battle of Arcis-sur-Aube , the emperor and his staff were threatened by opposing cavalry, but the Polish escadron on duty under Skarżyński was able to clear up the situation. Despite the French withdrawal, the Allies still feared Napoleon and decided to accelerate the advance on Paris. Most of the regiment was not involved in the battle of Paris , only a few riders from the depot and 80 "Éclaireurs polonais" under Jan Leon Kozietulski were assigned to the small guard cavalry brigade under Dautancourt. First sent to Villette , the guardsmen defended the hill of Montmartre in vain and tried to stop the progress of the Allies. The fighting continued in the vineyards of Clichy , but the brigade, under intense fire, fled behind the ramparts and gathered on the Boulevard des Italiens , where they learned of the surrender of Paris.

The "Escadron Napoléon"

Napoléon had to make way for the first restoration . The "Regiment des lanciers polonais de la Garde" was excluded from the French army and dissolved. Led by Krasiński, presented it to Grand Duke Konstantin in Paris and then set off for Poland. This route was often associated with problems, mainly when crossing the Prussian territories. Once at home, the unit was integrated into the army of the Kingdom of Poland .

The return of the Bourbons did not end the regiment's existence for good, however. The Treaty of Fontainebleau granted Napoleon the island of Elba and a guard of 1,000 men. The "Lanciers polonais" were included in this guard. 108 volunteers formed an escadron under the command of Major Baron Paweł Jerzmanowski, which was called "Escadron Napoléon". This consisted of six officers, two trumpeters, 11 NCOs and 90 horsemen. Seven chasseurs à cheval de la Garde were assigned . The Escadron divided into two companies - a mounted company under Capitaine Schultz (known because of his height of 2.10 meters) with 22 riders and a company on foot under Capitaine Baliński with 96 men. The operation was carried out by two lancers as guards in the palace and 33 men as guards. The Escadron was also used in the artillery service and in the stable watch. The Poles were housed in the building opposite the Palazzina dei Mulini, Napoléon's quarter.

After Napoléon had decided to return to France, Jerzmanowski received the order on the evening of February 25, 1815, to board the ship Le Saint-Esprit with his men . On March 1st, the Lancers were back in France.

Waterloo: the final attack

After Napoléon had initially returned to the throne and the reign of the Hundred Days had begun, the lancers of Paweł Jerzmanowski were housed in the Caserne des Célestins, where conditions were poor:

"Les cavaliers couchent sur la paille et il n'y a guère de place à l'écurie pour les chevaux qui restent dehors. »

"The riders sleep on the straw in the stable and there is not enough space for the horses, so they have to stay outside."

During the campaign in Belgium, the Poles formed the 1st Escadron in the 2nd Regiment of the Chevau-légers lanciers de la Garde. In the Battle of Ligny, the Escadron Jerzmanowski attacked the Prussians von Blücher. In an attack on the Nassau infantry near Frasnes, the "Lanciers polonais" suffered losses.

In the battle of Waterloo the Poles in the regiment of the "Lanciers rouges" carried out several unsuccessful attacks. Despite the later support of the heavy cavalry of the Guard, the Lancers had to surrender without having ousted the Anglo Allies of Mont-Saint-Jean. On June 23, the Escadron consisted of only 72 men. Eight men were killed, 31 were missing and Major Jerzmanowski was wounded. After the defeat, the "Chevau-légers lanciers polonais" were ordered behind the Loire under the command of Maréchal Davout. On October 1, the unit was definitively dissolved and the remaining riders integrated into the Russian army. Major Jerzmanowski expressed the wish to accompany the emperor into exile in St. Helena , but this was rejected by the victors.

Traditions

In the Second Polish Republic , the tradition of the "Lanciers polonais de la Garde" was continued by the 1st Regiment Chevau-légers Józef Piłsudski ( Polish 1 Pulk Szwoleżerów Józefa Piłsudskiego ). The 2nd Escadron served as guard of the Polish President.

Since the mid-1990s, the “return of the Chevau-légers” festival is celebrated in August in Ciechanów and Opinogóra . During the event, delegations from Poland, Great Britain, Belarus , Lithuania and Latvia will present themselves in historical uniforms.

Commanders

On April 17, 1808 Wincenty Krasinski, a former officer in the staff of Napoleon, intended for the Colonel "Chevau-légers polonais" and remained in that post until 1814. Major s premier was Antoine Charles Bernard Delaitre , veteran of the Egyptian campaign and former member the Mamelouks de la Garde impériale , Major en second was Pierre Dautancourt of the "Gendarmerie d'élite de la Garde impériale" and participant in the trial of Louis Antoine Henri de Bourbon-Condé, duc d'Enghien . In November 1813 he was transferred to the post of Major en premier . In 1812 Delaitre left the regiment and was appointed Colonel of the Lanciers lituaniens de la Garde impériale on July 5 and replaced by Jan Konopka. During the Russian campaign and the following campaign in Germany, Dominique Hieronime Radziwill held the post of major en second until he died on November 11, 1813 from the wounds he had suffered in the battle of Hanau. On May 30th, Jan Leon Kozietulski also became Colonel en second .

The Escadron de l'île d'Elbe (Elba-Escadron) was under the command of Colonel-Major Paweł Jerzmanowski, who had distinguished himself in the rearguard during the Russian campaign. After Napoléon returned to France in 1815, the Général Dautancourt offered himself as commander of the "Lanciers polonais", but was not considered. Instead, Jerzmanowski was given command.

Standards

The first aigle de drapeau with the flag was given to the regiment by Napoléon in 1811 on the occasion of a parade in the Tuileries. It was from the 1804 model in Pierre-Philippe Thomire's studio.

In the Napoleonic era, a total of four eagle-bearers were named: the lieutenants Jordain, Verhagen, Zawidzki and Rostworowski. In 1813 the new model 1812 was issued, which remained in use until the restoration in 1814. This was followed by the white standard, which was used on Elba and also during the reign of the Hundred Days.

Uniforms

The regiment's uniforms were in the colors of the former Polish noble cavalry. When the unit was set up, the price for a uniform of the best quality was 835 francs per man . Since the empire bled to death in 1813 and was no longer able to produce such high-quality parts, the quality and with it the price fell to 391 francs.

Teams

The regiment wore a Tschapka as a national Polish peculiarity, on the front of which there was a copper shield with an embossed "N" with a crown. The lower (round) part of the body of the Tschapka was covered with a black and white ribbon, the upper part with dark carmine-red fabric. At the top was a white plume. The cords were white and red, but only served as an ornament. Two flat knots and white acorns were attached to it. The silver-framed Maltese cross was located in a cockade under the sleeve of the spring stub . The Tschapka was equipped with yellow metal scale chains as a chin strap. When it was set up, the regiment had a parade uniform made of a white kurtka with a crimson breast discount and crimson trousers. However, this equipment was soon abandoned because of its high procurement costs and proven uselessness.

The second Kurtka had then prevailed. She was dark blue with white buttons and ruby rebates , which was edged with silver braid. The stand-up collar was also carmine with a silver border. The pockets were edged with red piping . The shoulder cords (aiguillette) and the epaulettes were interwoven in white with red (carmine for the NCOs). Between 1807 and 1809 the guards' aiguillette was worn on the right shoulder and a fringed epaulette on the left shoulder. After the introduction of the lance, the carrying arrangement (except for the officers) was reversed to improve the handling of the weapon. The ranks were indicated by silver angles. The white coat of the rider was specially designed for the use of the lance and was called "manteau-capote". It replaced an earlier sleeveless cloak that had proven impractical after the introduction of the new weapon.

On the march, the chapka was covered with a black oilcloth, which only exposed the scale chains. The Chevau-légers wore a blue kurtka without embellishments and either blue or gray overbutton trousers with crimson side stripes. A red cap (bonnet de police) with a silver border and a blue, white piped flame on the top was worn for stable duty . This included button-on stable trousers made of white or gray linen.

trumpeter

1807 to 1810

There were two models of hats for the trumpeters, corresponding to two consecutive periods: the first (worn from 1807 to 1810) was identical to that of the troupe, with the exception of the gold metal chin strap and the lack of flat knots. The first uniform was crimson with white borders edged with silver. The aiguillette and the epaulette were both white, the same was true of the collar. The trousers were crimson with silver borders. For the marching uniform, the borders were red with white passepoils and the pants were made of black fabric with crimson stripes and a button placket.

1810 to 1814

The second model appeared in 1810 and brought several changes with it. The fluted top of the Tschapka changed from red to white with red piping; the feathers were also white now, as were the cords. The flat knots were reintroduced and appeared in red and white. The black oilcloth protected the shako on the march. However, the pants remained crimson with silver side stripes. The little uniform was made of sky-blue fabric with crimson borders and silver trimmings, while the aiguillette was alternately plaited in white and red. The pants were Turkish blue with crimson stripes. All trumpeters were mounted with white horses.

instrument

The so-called "trompette" was a valveless fanfare made of brass, which was decorated with a cloth and braided ribbons. The decorative cloths were made of crimson silk with red and white fringes and plaited tassels . The embroidery on one side showed a crowned “N” made of gold wire, which was surrounded by a silver laurel wreath. Underneath was a silver-embroidered banderole with the inscription “Garde impériale”. The edges of the cloth were lined with white wire and trimmed with the same piping. The other side was adorned with the same laurel pattern, in the center was a crowned eagle made of gold wire on a silver sun. The banderole bore the inscription "Chevau-légers polonais" and was located between the wings of the eagle. (On contemporary illustrations there are differences in the heraldic arrangement of the front and back.)

Kettledrum

The regiment's kettledrum, Louis Robiquet, appeared at the wedding of Napoléon and Marie-Louise of Austria in 1810. He has been missing in Russia since the withdrawal and his post has not been refilled.

He wore a "Confederatka", a flat, black cap with a chapka top made of crimson and gold-plated, ribbed fabric. There was a white and a red plume at the top. The jacket was crimson with buttons and piping of gold thread. A sleeveless white tunic embroidered with gold was worn over it and reached the middle of the legs. The belt consisted of a crimson scarf with a gold thread. The pants were sky blue with gold stripes on the sides, and the boots were made of brown leather.

The two large kettledrums that were attached to each side of the horse were covered with red cloth embroidered with a laurel wreath and with a golden eagle in the center. Stars made of silver thread and gold embroidery were sewn onto the entire cloth. The inscription "Chevau-légers polonais" was on a silver banderole. The gray horse wore a crimson saddlecloth with gold braids, fringes and imposing embroidery in gold threads. The edge was decorated with red and white feathers and red tassels.

Officers

The officer's Tschapkas were of the same color as those of the NCOs and men. However, the lower area consisted of a black and crimson band instead of the black and white band of the teams. The red part was embroidered with leaves made of silver wire. The Maltese cross was on a three-colored cockade, which was more imposing than that of the teams.

Colonel Krasiński ordered a large uniform (grande tenue) for the senior officers at parades . It consisted of a white skirt with crimson chest discounts and a collar. The latter were decorated with gold braids and silver embroidery. As a special feature, there was a silver epaulette with fringes of the same color on each shoulder. English eyewitnesses reported that at Waterloo officers of the Escadron wore this uniform instead of the field uniform.

The uniform of the senior officers was similar to that of the enlisted men (blue cloth with chest discounts and crimson collar), but with a few differences: embroidery made of silver threads was attached to the borders. Unlike the Colonel's uniform, the aiguillette was attached to a flap without an epaulette. In addition, the trousers were crimson with silver stripes on the sides, the officers wore a gray silk scarf with red stripes around their waist.

The field uniform consisted of a Turkish blue kurtka without cuffs with a white epaulette and aiguillette. The Tschapka was covered with a beige-colored cloth, but there were no changes to the trousers. The officers also wore an all-white dress uniform with borders, cuffs, and crimson collars. This included a black felt hat and trousers with white silk stockings. Except for the blue cloth jacket, the lapels and the bicorn with the white plume, these clothes were identical to the formal uniform. The little uniform (called tenue de quartier ) consisted of a confederatka, a Turkish blue skirt without borders with an epaulette and aiguillette and trousers with crimson side stripes.

Armament and equipment

When it was set up in 1807, the lancers were equipped with a saber , a musket (Mousqueton) and a pistol . The parts came from Prussian stocks and were of poor quality.

In 1809 they received the saber as used by the Chasseurs à cheval de la Garde. The dimensions of the pistols and mousquetons were in accordance with French regulations. The lance, introduced in 1809, was 2.75 meters long, made of wood and painted black. A red and white lance flag was attached to the top. It was kept in a leather shoe that was attached to the left side of the dark blue saddle pad. The "Mousqueton modèle an IX" was a little longer than 1 meter and could be attached to both sides of the saddle.

The Chevau-léger's cartridge was made of black leather with a crowned eagle made of copper. The shoulder strap was made of white leather, as was the shoulder strap of the saber. The cartridges of the trumpeters were like those of the riders. The officer's shoulder strap was also made of white leather, but lined with red. On the belt was a crowned eagle with a chain to a coat of arms, all gold-plated. The cartouche was made of white leather with gilded passepoiles, on the lid a gilded sun with an eagle in the center.

Horse armor

The rider's saddlecloth was made of the same cloth as the kurtka with a crimson border and white piping. The embroidery consisted of a crowned "N" made of white thread on the front and a crowned eagle in the same color on the back. The trumpet's saddlecloth for the large uniform was the same as that of the rider. It was not changed for the service uniform. The second saddle pad for the parade was crimson and had white borders. The coat bag was crimson red with white piping for both types of uniform. For the senior officers it was done in dark Turkish blue, surrounded by two silver borders with red piping. The embroidery was the same as on the crew. The lower officer ranks only had a silver border. The officers could have the saddle covered with a panther skin. The rest of the equipment of the horse corresponded to that of the light cavalry.

Historical processing

The role of the "Lanciers polonais de la Garde impériale" in the Napoleonic Wars culminated in the attack at Somosierra. It became the common interest of French, English and Polish historians who wrote many right and wrong things about this episode. There were also errors and inaccuracies in the contemporary work of Colonel Niegolewski, published in 1854. Other disagreements regarding the regiment's deployment at Reichenbach in 1813 led to scientific controversy and contradictions between the various authors regarding the presence of the Poles and the extent of their deployment.

Somosierra

Years later, the battle was still the subject of intense discussion between Adolphe Thiers and Colonel Niegolewski, who accused the French historian of downplaying the role of the Poles on that day. Between 1845 and 1862 the historian Adolphe Thiers published his work Histoire du Consulat et l'Empire in 20 volumes. From page 365 in the ninth volume he devoted himself in particular to the attack by the Chevau-légers polonais near Somosierra:

«Le premier escadron essuya une décharge qui le with en désordre en abattant trente ou quarante cavaliers dans ses rangs, mais les escadrons qui suivaient, passant par-dessus les blessés, arrivèrent jusqu'aux pièces à sabrèrent les canonniers et prirent les feu. »

“The first Escadron took a full volley that messed up the ranks and knocked 30 or 40 horsemen down. But the following escadrons rode over the injured, reached the gun emplacements, sabered the waitress and captured the 16 cannons. "

Colonel Andrzej Niegolewski as a participant in the fight was dissatisfied with this version. To correct the historical truth, he wrote several letters to the author and was assisted by General Krasiński, the former regimental commander.

The then Lieutenant of the Chevau-légers emphasized the many inaccuracies in the execution of Thiers, in particular that the first attack was not carried out by the 1st Escadron but by the 3rd Escadron and that it was the latter that made it, the cannons To conquer, the 1st, 2nd and 4th Escadron had only carried out the pursuit of the fugitives. He also denied that Général Louis Pierre de Montbrun led the attack, although this was circulated through the official bulletin and so adopted by Thiers. This error was then adopted by Jean Tranié and Juan-Carlos Carmigniani in their 1982 publication Les Polonais de Napoléon , who write on page 40 about Montbrun:

«[…] The charge avec les chevau-légers polonais à Somo-Sierra. »

"[...] he attacked at the head of the Chevau-légers polonais near Somo-Sierra."

Niegolewski explicitly accused Adolphe Thiers:

«[…] Ternir l'éclat de nos grandes actions. »

"[...] he diminishes the shine of our great deeds."

Thiers responded by promising Niegolewski a reprint of Volume IX in which this point of criticism should be cleared up. As a result, a book by Colonel Andrzej Niegolewski was published in 1854 with the title:

- Les Polonais en Somo-Sierra, en 1808, en Espagne. Réfutations et rectifications relatives à l'attaque de Somo-Sierra décrite dans le IX e volume de l'Histoire du Consulat et l'Empire, par MA Thiers

Reichenbach and Peterswalde

Another dispute arose after the publication of the Battle of Reichenbach (May 22, 1813) with several officers of the "Lanciers rouges" (2nd regiment) of the Imperial Guard. The latter noticed that their regiment was facing a large Russian cavalry unit and that it succeeded in routing the enemy at the expense of heavy losses. However, the same documents did not mention the support of the rest of the cavalry of the Guard or the use of the "Lanciers polonais" of the 1st regiment. Thiers also attributed the main activities to the "Lanciers rouges" of the 2nd Colbert-Chabanais regiment .

General Dezydery Chłapowski - in 1813 chief d'escadron of the "Lanciers polonais" - for his part told his own version of things in which he insisted on the decisive role of his regiment without even mentioning the "Lanciers rouges".

There were similar disputes about the description of the battle near Peterswalde. In his Mémoires, Jósef Grabowski contradicted Thiers' statements:

«M. Thiers (tome XVI, page 162) mentionne cette affaire, mais suivant son habitude de cacher les actions d'éclat des Polonais pour les attribuer aux Français, il dit que c'étaient les lanciers rouges de la garde impériale qui ont battu les hussards prussiens et fait prisonnier leur boss Blücher. J'étais témoin oculaire de cette action, et je peux affirmer que les lanciers rouges n'étaient pas là, et que ce sont les chevau-légers lanciers de la garde impériale qui ont si brillamment chargé. »

"A. Thiers (Volume XVI, page 162) mentions this event, but as usual has the habit of suppressing the brilliant deeds of the Poles and ascribing them to the French. He says that it was the 'Lanciers rouges' of the Imperial Guard who routed the Prussian hussars and took their commander Blücher prisoner. I was an eyewitness to this action and I can confirm that the 'Lanciers rouges' were not there at all and that it was the 'Chevau-légers lanciers' of the Imperial Guard who did so brilliantly. "

Individual evidence

- ↑ Brandys, 1982, p. 78.

- ↑ Tranié / Carmigniani, 1982, pp. 9, 12.

- ↑ Pawly, 2007, p. 6.

- ↑ Tranié, 2007, p. 7.

- ↑ Tranié, 1982, p. 21.

- ↑ Tranié, 2007, p. 7.

- ↑ Pawly, 2007, p. 7.

- ↑ Tranié, 2007, p. 7.

- ↑ In the French cavalry, the barracks are called quarters .

- ↑ the large stable building

- ↑ Pigeard, 1999, pp. 25-28.

- ↑ Tranié / Carmigniani, 1982, p. 13.

- ↑ Hourtoulle, 1979, pp. 177-184.

- ↑ Malibran, 2001, p. 57.

- ↑ Pawly, 2007, p. 20.

- ↑ Tranié, 1982, p. 38.

- ↑ Tranié, 1982, p. 38.

- ^ Niegolewski, 1854, pp. 12, 23, 24.

- ↑ Pawly, 2007, p. 20.

- ↑ Brandys, 1982, p. 160.

- ↑ Tranié, 1982, pp. 62, 70.

- ↑ Tranié, 2007, p. 11.

- ↑ Tranié / Carmigniani, 1982, p. 77.

- ↑ Pawly, 2007, p. 24.

- ↑ Brandys, 1982, p. 224.

- ↑ Brandys, 1982, p. 225.

- ↑ Pigeard, 1999, pp. 22, 23.

- ↑ Brandys, 1982, p. 122.

- ↑ Pawly, 1998, p. 31.

- ↑ Chłapowski, 1908, pp. 257–260.

- ↑ Pawly, 1998, pp. 38-40.

- ↑ Pawly, 1998, p. 40.

- ↑ Pawly, 1998, pp. 40-42.

- ↑ Pawly, 2007, p. 39.

- ↑ Tranié / Carmigniani, 1982, p 107th

- ↑ Brandys, 1982, p. 147.

- ↑ Mané, 2013, p. 2.

- ↑ Chłapowski, 1908, pp. 330–342.

- ↑ Pawly, 2007, p. 40.

- ↑ Kukiel, 1996, p. 455.

- ↑ Brandys, 1982, p. 164.

- ↑ Tranié / Carmigniani, 1982, p. 127.

- ↑ Perrot / Amoudru, 1821, p. 431.

- ↑ Tranié / Carmigniani, 1987, p. 174.

- ↑ Brandys, 1982, p. 412.

- ↑ Tranié / Carmigniani, 1982, p. 160.

- ↑ Kukiel, 1996, p. 475.

- ↑ Leżeński / Kukawski, 1991, pp. 70, 144.

- ↑ Chief of the regimental administration

- ↑ According to Eugène Louis Bucquoy, however, the piping was red.

- ↑ Bucquoy states that all officers wore two epaulettes.

- ↑ Bucquoy, 1977, p. 128.

- ↑ Thiers, 1849, p. 365.

- ^ Niegolewski, 1854, pp. 21, 64.

- ^ Niegolewski, 1854, p. 40.

- ^ The Poles at Somo-Sierra in Spain in 1808. Refutations and corrections regarding the attack at Somo-Sierra, described in IX. Volume of "Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire" by A. Thiers .

- ↑ Gasiorowski, 1907, p. 120 ( digitized on Gallica ).

literature

history

- Jean Tranié, Juan-Carlos Carmigniani: Les Polonais de Napoléon. L'épopée du 1 er régiment de lanciers de la garde impériale . Copernic, Paris 1982.

- Charles-Henry Tranié: Les chevau-légers polonais de la Garde impériale . In: Soldats of Napoléonia . No. 16, December 20, 2007.

- Ronald Pawly: Les Lanciers Rouges . De Krijger, Erpe-Mere 1998, ISBN 90-72547-50-0 .

- Alain Pigeard: Les units de la Garde impériale . In: "Tradition Magazine", No. 8, January 1, 1999 (= Napoléon et les troupes polonaises 1797–1815. De l'Armée d'Italie à la Grande Armée ).

- Philip Haythornthwaite: La Garde impériale . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2004, ISBN 2-84349-178-9 . (= Grandes Armées. No. I. Armées et batailles. No. 1)

- A. Perrot, Ch.Amoudru: Histoire de l'ex-Garde depuis sa formation jusqu'à son licenciement, comprenant les faits généraux des campagnes de 1805 à 1815 . Delaunay, 1821 ( digitized on Gallica , full text in the Google book search).

- Andrzej Niegolewski: Les Polonais à Somo-Sierra en 1808 en Espagne. Réfutations et rectifications relatives à l'attaque de Somo-Sierra décrite dans le IX e volume de L'Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, par MA Thiers . L. Martinet, Paris 1854 ( digitized version ).

- Dezydery Chłapowski: Mémoires sur les guerres de Napoléon, 1806–1813 . Plon-Nourrit, Paris 1908 ( digitized version ).

- Ronald Pawly: Napoleon's Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-1-84603-256-1 . (= Men-at-Arms. Volume 440)

- Marian Brandys: Kozietulski i inni . Iskry, Warszawa 1982, ISBN 83-207-0463-4 .

General overview

- Jean Tranié, Juan-Carlos Carmigniani: Napoléon (1814 - La campagne de France) . Pygmalion / Gérard Watelet, Paris 1989, ISBN 2-85704-301-5 .

- Jean Tranié, Juan-Carlos Carmigniani: Napoléon (1813 - La campagne d'Allemagne) . Pygmalion / Gérard Watelet, Paris 1987, ISBN 2-85704-237-X .

- Henry Houssaye: 1815. Perrin, Paris 1921 (revised and amended edition, full text in the Google book search).

- Bruno Colson: Leipzig. La bataille des Nations. 16–19 October 1813. La première défaite de Napoléon . Perrin, Paris 2013, ISBN 978-2-262-04356-8 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- Alphonse Marie Malibran, Jan Chełmiński: L'armée du Duché de Varsovie, ou la contribution polonaise dans les rangs de la grande armée . Livres Chez Vous, Pétion-Ville 2001, ISBN 2-914288-02-6 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- François-Guy Hourtoulle; Jack Girbal (Ill.): Le Général Comte Charles Lasalle. 1775-1809. Premier cavalier de l'Empire. Copernic, Paris 1979, ISBN 2-85984-029-X ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- Diégo Mané: Reichenbach, le 22 may 1813 . In: Planète Napoléon . Lyon 2008/2013 (PDF; 444 kB).

- Waclaw Gasiorowski: Mémoires militaires de Joseph Grabowski. Officier à l'état-major impérial de Napoléon I er , 1812-1813-1814 . Plon-Nourrit, Paris 1907, p. 120 ( digitized on Gallica ; new edition Pickle Partners Publishing, 2015).

- Adolphe Thiers : Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire , Volume IX. Paulin, Paris 1845 ( full text in the Google book search).

- Marian Kukiel: Dzieje oręża polskiego w epoce napoleońskiej . Kurpisz, Poznań 1996, ISBN 83-86600-51-9 , OCLC 891024130 .

- Cezary Leżeński, Lesław Kukawski: O kawalerii polskiej XX wieku . Ossolineum, Wrocław 1991, ISBN 83-04-03364-X ( limited preview in Google book search).

Uniformology

- Liliane and Fred Funcken: L'uniforme et les armes des soldats du Premier Empire , Volume 2: De la garde impériale aux troupes alliées, suédoises, autrichiennes et russes . Casterman, Tournai 1969, ISBN 2-203-14306-1 .

- Eugène-Louis Bucquoy: La Garde Impériale. Troupes à cheval , Volume 2. Jacques Grancher, Paris 1977, ISBN 84-399-7086-2 , Chapter: Le 1 er Régiment de Chevau-Légers Lanciers Polonais . (= Les Uniformes du Premier Empire )

- Lucien Rousselot: Chevau-leggers polonais de la Garde. 1807-1814 . Volume IP Spadem, 1979, No. 47. (= L'Armée Française, ses uniformes, son armement, son équipement )

- Lucien Rousselot: Chevau-leggers polonais de la Garde. Trompettes. 1807-1814 . Volume II. P. Spadem, 1980, No. 65. (= L'Armée Française, ses uniformes, son armement, son équipement )

- Lucien Rousselot: Chevau-leggers polonais de la Garde. Officiers. 1807-1814 . Volume II. P. Spadem, 1980, No. 75. (= L'Armée Française, ses uniformes, son armement, son équipement )