Battle of Laon

| date | March 9 and 10 , 1814 |

|---|---|

| place | Laon in Picardy , France |

| output | Napoleon's retreat |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 30,000 | 103,800 |

| losses | |

|

6,000 |

4,000 |

Spring campaign 1813

Lüneburg - Möckern - Halle - Großgörschen - Gersdorf - Bautzen - Reichenbach - Nettelnburg - Haynau - Luckau

Autumn campaign 1813

Großbeeren - Katzbach - Dresden - Hagelberg - Kulm - Dennewitz - Göhrde - Altenburg - Wittenberg - Wartenburg - Liebertwolkwitz - Leipzig - Torgau - Hanau - Hochheim - Danzig

Winter campaign 1814

Épinal - Colombey - Brienne - La Rothière - Champaubert - Montmirail - Château-Thierry - Vauchamps - Mormant - Montereau - Bar-sur-Aube - Soissons - Craonne - Laon - Reims - Arcis-sur-Aube - Fère-Champenoise - Saint -Dizier - Claye - Villeparisis - Paris

Summer campaign of 1815

Quatre-Bras - Ligny - Waterloo - Wavre - Paris

The Battle of Laon took place on 9 and 10 March 1814 during the winter campaign in 1814 the War of Liberation in France. On these days, the French army under Napoleon Bonaparte attacked the far superior Silesian Army of the 6th Coalition under Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher near the French city of Laon. The French army was repulsed on both days with heavy losses and withdrew to Soissons on the Aisne on the night of March 11, 1814 .

prehistory

On Monday, March 7th, 1814 Napoleon delivered the battle of Craonne to the Silesian army along the Chemin des Dames from Craonne to Braye . On March 8, 1814, most of his exhausted troops were allowed to rest and Napoléon moved his headquarters to Chevregny. Napoleon probably hoped he could succeed in driving the Silesian Army further north and forcing them to withdraw to Belgium. In any case, he was determined to attack the coalition troops wherever he found them, and with this intention already on the evening of March 8, 1814 and on the night of March 9, sent his first troops north against Laon.

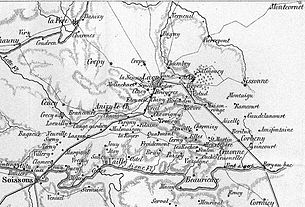

Topography of the battlefield

(some of the places were lost in the First World War and can no longer be found today)

The old town of Laon is on a witness Berg mentioned geological formation de France on the edge of the Ile towers above the surrounding plain by about 100 meters. The mountain is made up of layers of sand and clay, rocky parts are made of limestone. The clay is highly water-bearing and feeds a number of springs and wells at the foot of the mountain below the old city wall .

The flattened altitude of the free-standing mountain, divided by individual gorges, has always been built on and heavily fortified. The entire upper town on the mountain was surrounded by a wall with numerous defensive towers in which seven gates led into the town. In 1814 the fortifications had already started to crumble and there were first gaps in the city wall. On the southern slopes below the city, where the soil allowed, wine was grown. If not, gardens were laid out, separated and subdivided in the French style by walls.

The area around Laon was very humid and swampy in 1814, especially in the south of the city. There, south of the city, the terrain is undulating and was - like today - heavily forested. In the north the land is flat and fertile, agriculture predominated. There was little village settlement below the mountain. To the southwest of Laon at the foot of the mountain and on the road to Soissons lies the town of Semilly, in the same direction the hidden village of Clacy. Exactly in the south in front of the city was the place Ardon, which is now completely in the urban area. Athies is east of Laon and north of the road to Berry-au-Bac. The fighting was concentrated in these four places.

Two paved roads led from the south to Laon in 1814: from the south-west the road from Paris via Soissons, which led via Chavignon and north of the village of Etouvelles for a good kilometer over dams through the swamps to Laon. The second road led from Reims via Berry-au-Bac, Corbeny and Festieux to Laon. Before the village of Athies this road turns west so that it reaches Laon from the east. Between the two streets was an extensive swamp area, in which only a dry headland stretched north from the village of Bruyères to Laon. Those who wanted to switch from one street to the other and had to avoid Laon were forced to go far south because of the swamps. This circumstance made communication between the French contingents involved considerably more difficult.

Battle of the Eve on March 8, 1814

On March 8, 1814, coalition troops withdrew from the battle of Craonne across the road from Soissons north to Laon. From 10:00 in the morning there were the first skirmishes of retreat with the Napoleonic troops, who came down from the Chemin des Dames or moved down the Ailette and came across the great road from Soissons to Laon near Chavignon.

First the French met General Benckendorff's Cossacks at the Ailette , who had to retreat quickly to Corbeny and then further north. There they united with the troops of the Russian general Tschernyschow, who had used the narrow point at the village Etouvelles, from where the road was led over a dam through the swamp, to build a first defensive position south of Laon. In this position there were two regiments of infantry and 24 guns. Blücher had ordered him to hold up the advancing French until the entire “Silesian Army” had taken up secure positions near Laon. Napoléon, on the other hand, sent Marshal Ney ahead with selected troops to disrupt the "Silesian Army" as early as possible. Ney had Chernyshev's position attacked three times without success before dark. When it was dark and the French stopped fighting, Chernyshev split up his troops, withdrew 18 guns and set up a second defensive position further north near the small village of Chivy-lès-Etouvelles.

Night battle at Etouvelle and Chivi on the morning of March 9, 1814

Napoléon accepted the service of local people, who offered him to lead his troops on two hidden footpaths behind the Russian positions. A unit of soldiers of the "Old Guard" and cavalry riders was placed under the command of General Gourgaud and marched off with their local leaders at 11:00, with the intention of the Russians arriving at the agreed hour at 1:00 the next morning To attack Chivy-lès-Etouvelles. They managed to remain undetected during their march, but since it began to snow in the cold night and the roads were in poor condition, they were delayed.

Marshal Ney and 400 volunteers from the Spanish brigade proceeded again in the dark. At the appointed hour at 1:00 a.m., they surprised their exhausted Russian opponents from the previous day in their sleep at Etouvelle. Marshal Ney's men also managed to take the dam leading to Chivry by storm, but there they encountered energetic resistance from the Russians under Chernyshev and further advance was initially not possible. At 2:00 a.m., Gourgaud and his men also arrived at Chivry, but it was not until 4:00 a.m. that Chernyshev and his men, after suffering considerable losses, withdrew and settled in the village of Clacy. This cleared the way for Napoléon's troops.

Napoléon sent cavalry troops under General Belliard with the order to follow the retreating Russians and, if possible, to penetrate with them into Laon. So the French cavalry appeared at Semilly at 5:30 a.m., where they were surprised by violent fire from Prussian artillery, lost many riders in the first ranks and immediately withdrew into the cover of darkness and the woods to wait for dusk. The same thing happened to Gourgaud's cavalry at Clacy. She had to withdraw and wait for the day in the woods between Chivy and Semilly.

Napoleon spent that night in Chavignon.

First day of battle: March 9, 1814

Position of the coalition troops

The "Silesian Army" had taken positions around Laon. The town itself, the mountain slopes and the village of Semilly were occupied by the Bülow corps. A closed line of snipers stood in front of the troops, some in the village of Ardon. Over a hundred cannons were ready for action on the city walls and in front of them.

To the west of Laon stood the Russian Corps Wintzingerode, to the east of the city the Prussian Corps Yorck. Its troops comprised the village of Athies to the west and north, but only parts of it were occupied because its inhabitants had shown themselves hostile and had defended themselves with weapons. The Prussians then had all the inhabitants of the village they could get hold of, especially the old and sick, and made arrangements to burn the houses down. Kleist's Prussian Corps stood on the road to and from Berry-au-Bac. Guns had been positioned in front of the infantry.

The cavalry had been split up and reassigned to the corps. It stood in a northerly direction behind the infantry, Prussian cavalry under Zieten in large numbers northeast of Athies. Two Prussian cavalry regiments stood near the village of Eppes with a clear view of the street. Five squadrons were waiting outside Festieux to report immediately if French troops were to approach on this road. Cossacks roamed as far as the Aisne and caused unrest among the French.

To the northeast of Laon, the Russian Sacken and Langeron corps were positioned so that they could be deployed on both sides of the city.

Blucher's headquarters were in Laon.

Strength of coalition forces

| Corps commander | Corps strength |

|---|---|

| Yorck | 13,500 |

| Kleist | 10,600 |

| Bülow | 16,900 |

| Langeron | 24,900 |

| Sacks | 12,700 |

| Wintzingerode | 25,200 |

| total | 103,800 |

The total strength was about 103,800 men, including about 20,000 horsemen and 7,500 Cossacks in 30 groups. About 500 guns were available. The ratio of Russians to Prussians was 6: 4. On both days together, 60,000 men of the Silesian Army came into action.

At 9 a.m. on March 9, 1814, the Russian soldiers who had held Soissons until the evening of March 7, 1814, arrived on the road from La Fère. When they found out that the direct route to Laon had already been blocked by the French, they had bypassed it extensively and reached Laon without loss.

Attack by the French under Napoleon in the southwest

Battles from 7:00 a.m.

The night from March 8th to 9th 1814 was wintry cold and it was snowing. At dawn, thick, viscous ground fog rose and visibility was poor. In the morning Napoleon ordered his corps to march to Laon. Because of the narrow passage at Etouvelle, these could only advance one after the other and reached Laon with some time lag.

Blucher had allowed himself to be persuaded by Chernyshev to reoccupy the post at Chivy-les-Etouvelles at dawn that had been given up at night. The individual infantry brigade that was sent forward for this purpose, however, was far too weak to stop the French when they advanced again in the early morning. When there was a danger that French cavalry might encircle the brigade, Cossacks came over, fought their line of retreat free and enabled their retreat to Laon.

The French officers could hardly see the positions of their opponents in the thick fog. That did not prevent them from attacking the villages of Semilly and Ardon with their men. At 9:00 in the morning the "Spanish Brigade" penetrated Semilly, but was pushed out again by the Prussian garrison and other rushing Prussian troops of the Bülow Corps. The French first settled in trenches 200 meters south of the village and shot at it from there. They tried to storm Semilly several times during the day. They also managed to penetrate the village repeatedly, but were driven out of it each time, for which purpose Bülow had to send further reinforcements down from Laon.

The French division Poret de Morvan, which advanced against the village of Ardon, had greater success. The Prussian snipers entrenched there were quickly driven away and a French column advanced north of the village further up the mountainside. However, when this reached a height where there was no longer any fog, they were discovered and very quickly driven away by Prussian troops. The village of Ardon remained occupied by the French.

All the fighting in the morning was accompanied by heavy artillery fire on both sides, which forced the French in particular to change the positions of their troops in order not to expose them too much.

Battles from 11:00 a.m.

Blücher and his general staff had gathered on a southern bay window of the city wall. When the fog cleared at 11:00 a.m., they were able to see all positions from there. Blücher's chief of staff, Gneisenau, correctly estimated the strength of Napoleon's troops at 30,000 men. This correct estimate immediately led to serious mistakes in the Prussian military leadership. Since the latter stuck to their earlier overestimation of the French troop strength, the question arose where the apparently missing troops could still come from? When the news arrived around the same time that French troops were advancing on the road from Reims, it was assumed that this would be the main power of the French and the following measures were taken one after the other:

- The Russian corps Sacken and Langeron in reserve were ordered to move to the east side of the city for reinforcement

- The Bülow Corps was ordered to occupy the village of Ardon and to prevent the unification of the French contingents in the south-east and south-west.

- With the same task, Cossacks were sent to patrol as far as Bruyères in the south.

- The Wintzingerode Corps was ordered to attack in the south-west in order to tie up the French troops there or to drive them south.

Prussian troops of the Bülow Corps initially succeeded in driving the French out of Ardon. Since the retreating French dragoons and Polish Uhlans came to the aid, the Prussians could not advance further south. Conversely, the French managed to regain the upper hand after a while and counterattack to occupy Ardon again and to assert themselves there. The French, supported by their cavalry, advanced beyond Ardon to the foot of the mountain of Laon and the city gate to Ardon. Another French column bypassed Semilly and tried to reach the city gate to Soissons. It was able to drive out the strong Prussian artillery from both city gates. The French infantry had to return to their starting positions, the cavalry withdrew to the village of Leuilly. Bülow finally decided to use artillery in the valley to support his own troops.

Further to the west, the Russians reoccupied the village of Clacy in a coup d'état, but were unable to advance because the French quickly strengthened themselves there too and vigorously defended themselves. The Russians later withdrew to their original positions, only one brigade remained in Clacy.

General Wassiltschikow succeeded with the hussars of the Sacken corps bypassing the French in the west and causing some unrest among them. But he too was too weak to force a lasting success and withdrew back to his corps.

The actions of the Prussians and Russians were carried out too hesitantly and with too weak forces to seriously damage or to drive Napoleon's army.

During all these hours Napoleon dispatched couriers every half hour to Marshal Marmont , who was advancing with his corps from Berry-au-Bac on the other road to Laon, as had been reported to Blücher and his General Staff. Napoléon asked Marmont to force his advance. None of these couriers reached Marmont; either they got lost or they were captured by the roaming Cossacks. On that day Napoleon remained completely ignorant of the whereabouts and actions of the Marmont Corps.

Battles from 4:00 p.m.

At 4 p.m. Napoléon ordered General Charpentier and his troops to retake the village of Clacy. Charpentier set four divisions in motion, who discovered that this village was surrounded by swamps and could only be reached by two routes. Most of the French troops were stranded in front of the swamps when one of their brigades managed to penetrate the place and take the few remaining Russians by surprise; 250 of them were captured, the rest withdrew to the north under the protection of their own artillery.

At the same time, Bülow sent several Prussian battalions against Ardon, which also succeeded in driving out the two French battalions of the Poret de Morvan division, which were still occupying the place. The French withdrew to Leuilly under the protection of their cavalry.

Both in front of Clacy and in front of Leuilly the engagement continued as an artillery duel until darkness stopped further fighting. Since there was not enough space between the marshes to bivouac all French troops off Laon, Napoléon withdrew with some of his troops, especially the "Old Guard", over the dam from Etouvelles to Chavignon.

Attack by the French Marmont Corps in the southeast

At 3:00 p.m. on March 9, 1814, the Marmont Corps appeared on the Berry-au-Bac road outside Laon. Marmont's corps had set out that morning from Corbeny and Berry-au-Bac, had waited at Festieux until the fog had cleared and only then had advanced further. When a division of the French attacked the village of Athies further north, with the support of their artillery, from the road on which they came up, the Prussians set fire to the village and retreated to its northern edge. Athies burned down completely by evening and the heat of the fires prevented the place from being occupied by any side until then.

Marmont had about 20 guns placed in an elevated position between the road and Athies and opened fire on the Prussian troops off Laon at 5:00 p.m. These returned the fire. At the great distance of 2000 meters, the effect on both sides was minimal. When darkness fell, the French artillerymen, who came largely from the Navy, gathered their guns in a park without taking any further precautions.

In the evening around 6:00 p.m., Marmont dispatched one of his officers with at least 400 horsemen and 4 guns to establish contact with the Napoleonic troops. This team used the direct route from Athies to Bruyères, which was now free.

Marmont went to Eppes for the night.

Blucher disease

Already around noon on March 9, 1814, an event of great importance for the following days became apparent: Blücher withdrew sick from the army command. He went to permanent quarters in Laon, demanded that the rooms be darkened, and did not leave them until further notice. Blücher's condition got worse and worse, he suddenly suffered from hallucinations and fear of death. His personal physician and his personal adjutant, Count Nostitz, were not allowed to leave him. Count Nostitz noted in his diary:

“When you saw him (Blücher) in this state, how he kept thinking of death with fearful anxiety, perceiving every pain with faintheartedness, how he tormented his imagination with the discovery of new symptoms of illness and, only concerned with himself, indifferent to everything was what was outside of him, even against the greatest and most important ... so one had to be amazed at the violence which the physical condition exercised over the spiritual powers. "

When Blücher was supposed to sign the order for the next day on the night of March 9th to 10th, 1814, he tried in vain to paint the individual letters of his name, but he did not succeed. For three consecutive days, the daily orders of the “Silesian Army”, all of which had been received in the original, were missing Blücher's signature. This fact became known to the troops and the rumor spread that Blücher was now mentally deranged.

In this situation, Blücher's chief of staff, Gneisenau, had to be solely responsible for command of the army, which was difficult for him, since he, who had never held a major command, did not enjoy a great reputation among Blücher's generals. When he urged the longest- serving corps commanders, Alexandre Langeron , to take over the high command from Blücher and thus allow the sick field marshal to leave for Brussels, Blücher, who was hardly accessible, then declined with the words: " Au nom de Dieu, transportons ce cadavre avec nous »( Alexandre Langeron after Müffling : From my life , German:“ In God's name, we will drag this carcass with us ”)

Blücher did not recover from his illness during the campaign. The old hussar officer could no longer ride and had to be driven in a curtained carriage in which he hid behind the veil of a lady's hat. To what extent he still had an influence on the events is unclear. He was relieved on April 2nd.

The contemporary literature gave an inflammation of the eye as the cause of the disease and was also limited to hints. More recent literature, on the other hand, speaks openly of a severe depressive episode that Blücher suffered.

Evening battle on March 9, 1814

As early as dawn, the Prussian General Yorck asked General Kleist whether he and his corps would take part in a night attack on the French Marmont Corps in front of them. Kleist immediately agreed. A similar request to the Russian Sacken Corps was refused; Yorck and Sacken had had a tense relationship since the battle of Montmirail on February 11, 1814. However, later the cavalry of the Russian corps Langeron and several Cossack pulks of the Russian corps Wintzingerode participated in the attack.

The two Prussian generals coordinated with the army command in Laon via couriers and provided cavalry for support, a total of 7,000 riders. At about 7:00 p.m., both corps quietly advanced to a bayonet attack, drove the few French who had ventured into the burning Athies in front of them and attacked the infantry of the Marmont Corps, whose men had just begun to light their bivouac fires. The surprise succeeded completely, the entire Marmont Corps got into disarray in the dark.

From the north, bypassing the village of Athies, the prepared cavalry attacked where the 2,000 riders of Marmont had last been seen. These were already dismounted and many were unable to get on the back of their horses before they all turned to flee south. Those French cavalrymen who intervened in battle on horseback increased the disorder even more, as they could not distinguish friend from foe in the dark, and indiscriminately also killed their own men.

Marmont's artillery suffered the greatest damage. Completely surprised and unprepared, the artillerymen tried either to use their guns or at least to save them. Where they were not killed by the Prussians, they lost most of their cannons, many of which overturned and fell into the ditch. The corps lost 45 guns that night and could only save 8. In addition, it lost at least 120 ammunition wagons. The loss of the artillery could, however, be compensated for in the next few days, as a transport came from Paris with cannons that were intended for the fortifications of Soissons, but were immediately transported to Fismes and handed over to the Marmont Corps.

Marmont came up from Eppes, but could not get an overview or create order. The few horsemen, however, whom Marmont had sent to Napoléon at around 6:00 p.m., heard the noise of battle on their way, and their officer was so independent that he decided to turn back. In the dark they fell to the side of Kleist's corps from the south and succeeded in driving the Prussians, who had now been surprised themselves, off the road and keeping them free for their corps to retreat. Many French people immediately gathered there, including Marshal Marmont. Now began a three-hour, bloody march of the French on the road back to Festieux, accompanied by the small number of remaining cavalrymen, constantly attacked and threatened by the overwhelming number of enemy horsemen. The Prussian officers let their trumpeters blow the signal very regularly, whereupon the Prussian troops aligned themselves and volleys shot at the French marching in the darkness in front of them.

The Prussian generals had enough time to send a strong cavalry contingent ahead, bypassing the French, which, accompanied by mounted artillery, was to relocate the rescue access to Festieux. It seemed at this point that the Marmont Corps was lost and would be taken completely captive. The rescue came from no more than 100 veterans of the Old Guard who had arrived in Festieux to guard a transport of military clothing from Paris. When these cold-blooded men suspected what was coming from the north, they seized two artillery pieces, holed up on the northern edge of the place and fired from there at the Prussians, who could not see in the dark how many opponents were in front of them, and immediately fell in withdrew the cover of darkness. So the remnants of the Marmont Corps were initially able to find protection in Festieux and entrench themselves there. When the place was secured, most of them moved on to Berry-au-Bac that night, where they were already threatened by the Cossacks who had rushed up.

The Prussians had taken a good 5,000 prisoners that night, half of whom ran away in the dark. In addition, Marmont lost 700 dead and wounded, but the Prussians also lost a few hundred men.

At the end of the night the Cossacks of Benckendorffs lurked in front of Berry-au-Bac, the Prussian cavalry and a number of infantry battalions stood north of Festieux, the rest of the Prussian infantry were again with Athies, and the Russian infantry of the Sacken and Langeron corps, who were hadn't moved, it said at Chambry.

The expulsion of the Marmont Corps was reported to the leadership of the "Silesian Army" before midnight. There they came to the conclusion that under these circumstances Napoleon could not attack again the next day, but had to withdraw. At midnight the order of the day for March 10, 1814 was issued: The Yorck and Kleist corps were ordered to continue to pursue the Marmont corps, the Sacken and Langeron corps had to follow them, but Longeron via Bryères, and to be ready for them To change the road to Soissons or to quickly cross the Aisne in order to stab Napoleon in the back and encircle him. The Bülow and Wintzingerode corps had to stop at Laon and follow Napoleon on his expected retreat. The departure had to take place at 4 a.m.

Second day of the battle: March 10, 1814

Early in the morning at 5:00 a.m. on March 10, 1814, two dragoons who had lost their mounts appeared on foot at Napoleon's headquarters and reported that the Marmont Corps had escaped and that the Marshal himself was missing. Napoleon didn't want to believe the news at first and sent riders to investigate the situation of the Marmont Corps. Confirmations soon arrived.

Napoleon now did what suited his disposition and what Blücher's general staff had thought impossible the night before: he ignored the bad news and attacked again.

But first his men had to defend themselves: General Charpentier had used the night to convert the difficult-to-reach village of Clacy into a small fortress: The narrow paths that led into the village from the north and east were each swept by three cannons A whole battery had been placed on the little hill in the village on which a chapel stood at that time. The Charpentier division had holed up in the village, behind it stood the Boyer de Reval division, a little off the road that went to the village of Mons to the west, was the "Spanish Brigade".

At 9:00 am, the Russian corps Wintzingerode received the order from Gneisenau to drive the French out of Clacy. An infantry division tried to enter Clacy while cavalry tried to reach Mons from the north. Since both villages were surrounded by swamps and forests, only a few paved roads remained to advance. The French let the Russians come within half range and then drove them into the sideways swamps and forests with the fire of their well-guided cannons.

With irreproachable stubbornness the Russian generals let men from one division after another march against Clacy, all of whom were repulsed by the French. Between 12:00 p.m. and 2:00 p.m. alone, five pointless and futile attacks were carried out on Clacy. The French suffered their greatest losses when the artillery of Ney's own corps accidentally shot at Clacy.

When the Prussian command of the "Silesian Army" realized that Napoleon did not intend to withdraw, they also recognized that the requirements for their own daily orders were no longer valid Sacks that were still at Bruyères and Chambray, respectively, and to the Prussian corps Yorck and Kleist, who were chasing the French Marmont corps on the way to Berry-au-Bac. All these corps were instructed not to march any further, but instead to await further orders from where they were. This instruction was followed with amazement and grumbling by the corps commanders.

At 14:00, under the impression of the events, Gneisenau ordered all corps to march back to Laon. Terror broke out among the commanders of the corps. Yorck and Kleist sent their personal aides back to Laon to present their objection. These were not admitted to Blücher and Gneisenau, concerned about his ultimate authority, insisted on his orders. The whole "Silesian Army" withdrew to Laon.

Also at 14:00 Gneisenau sent more troops to Clacy, but this time Prussian units of the Bülow Corps. Napoleon responded by sending his army forward to attack. The Russians in front of Clacy were driven out by the French divisions under the command of Charpentier, and Semilly was attacked. Mortier's corps captured Ardon, which the Prussians had evacuated that night in anticipation of the French retreat, and tried to take the slopes to the north of it. The attacks up the mountainside all failed in the fire of numerous Prussian guns. The Curial division went the furthest, bypassing Semilly and then climbing the slope towards the town in a broken formation. In the fire of the Prussian artillery, however, they could not hold out and had to return to the protection of the villages and forests.

Napoleon still refused to accept that it was not possible to storm Laon. He sent General Drouot to scout out to the edge of the forest in front of Clacy, near which Napoleon was. Drouot saw the mass of Russians in front of him and freely reported to Napoleon that a successful attack was not possible. Napoleon did not believe him and now sent General Belliard. The latter reported the same thing, and at 4:00 p.m. Napoleon finally gave the order to retreat to Soissons.

Since the corps of the "Silesian Army" were now on their way to Laon again, nobody prevented the French from retreating, only the Cossacks pursued them for a while: At first they were ambushed by the French rearguard and suffered unusual losses. But later they attacked the French entourage, looted 50 wagons and freed all prisoners from the hands of the French.

consequences

The commanders of the corps of the "Silesian Army" were violently angry about the performance of their own army command. Sacken went to Gneisenau and told him without make-up of his displeasure. Yorck behaved more drastically: after trying for a day to do what he could to help the residents of Athies, who had been played badly, he submitted his farewell, got into a carriage and left for Brussels. This behavior in turn sparked outrage: some high-ranking officers spoke of "desertion" and "shooting under the law". Blücher was informed and managed to write a three-line note to Yorck with the request to return. The Prussian Prince Wilhelm , the youngest brother of the Prussian king who served as lieutenant general in the "Silesian Army", wrote a letter to Yorck appealing to Yorck's loyalty to the king and asking him to return. Couriers with the letters were forwarded to Yorck, reached him and handed over their documents. Yorck read, considered, and returned. He was well aware of the difficulties he would face at home if he opposed the request of a senior member of the royal family.

But there were also other voices: General Bülow, who was most likely to have learned to judge and act independently, took the view that it was no longer worth sacrificing good men in a great decisive battle with Napoleon, since Napoleon was dealing with himself anyway Will bring crown and empire. Bülow was to be absolutely right.

With the renewed concentration of all units of the “Silesian Army” near Laon, the problem of supplying them came to the fore again. Langeron wrote a formal letter to Blücher on March 11, 1814, in which he pointed out that his men could no longer find anything to support themselves. On March 12, 1814, the corps had to move apart again so that each could take care of itself: the Bülow corps marched to La Fère on the Oise, the Langeron corps followed it, but further south, along the Ailette via Coucy-le-Château-Auffrique . The Sacken corps followed Napoleon directly, on March 12, 1814 to Chavignon, and the next day to Soissons. Yorck's corps marched on the road to Reims as far as Corbeny, and Kleist's corps to the west of it to Bouconville, and the next day to the Craonne plateau. In the daily order of March 12, 1814, the villages are listed for each corps that were in fact released for looting. Blücher and his General Staff remained in Laon with the Wintzingerode Corps.

The Marmont corps had initially gathered near the village of Condé-sur-Suippe, east of Berry-au-Bac and south of the Aisne, but was forced by the advancing Prussians to retreat to Fismes on the road from Soissons to Reims.

The slow shifts of the corps of the “Silesian Army” were not able to prevent Napoleon from taking the initiative again. He had arrived in Soissons at 3:00 a.m. on March 11, 1814. He spent March 11 and 12, 1814, in Soissons, planning and arranging reinforcements for the city's fortifications and regrouping his troops.

On these days, some unexpected reinforcements arrived in Soissons: around 2,000 cavalrymen, 1,000 recruits and 2 companies of artillerymen from the Garde de Côtes with the artillery transport already mentioned.

Napoleon now dissolved the corps of the injured Marshal Victor and the division of General Poret de Morvan, who was also injured. He formed a new cavalry division under General Berckheim, and two infantry divisions under Charpentier and Curial. Sebastiani replaced Nansouty as commander of the Guards Cavalry. Ney commanded the "Spanish Brigade".

On March 12, 1814, however, when it was reported to him that a mixed Russian-Prussian corps under General Saint-Priest had occupied Reims, Napoleon sent an order to Marshal Marmont in Fismes to march to Reims at dawn the next day. In the evening of the day, Ney's brigade, the division of the Old Guard under Friant, the guard cavalry and the reserve artillery set out from Soissons for Reims. Despite a distance of 58 km, Napoleon and his troops were already in front of Reims in the afternoon of the next day and completely wiped out the Corps Saint-Priest, while the soldiers of the "Silesian Army" further north searched the houses and barns of the farmers for food.

Most important people in the event

- the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte

- the Prussian Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher

- the Prussian general August Neidhardt von Gneisenau

- the Prussian general Friedrich Wilhelm Bülow von Dennewitz

- the Prussian general Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg

- the Prussian general Friedrich von Kleist

- the general in Russian service Ferdinand von Wintzingerode

- the general in Russian service Fabian Gottlieb von der Osten-Sacken

- the general in Russian service Alexandre Andrault de Langeron

- the Russian general Prince Alexander Ivanovich Tschernyschow

- the general in Russian service Konstantin von Benckendorff

- the French Marshal Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont

- the French Marshal Édouard Adolphe Mortier

- the French Marshal Michel Ney

- the French general of the artillery Antoine Drouot

- the French general Augustin-Daniel Belliard

Coordinates of the most important places of the event

- The village of Semilly, southwest of Laon: 49 ° 33 ′ 15 " N , 3 ° 36 ′ 23.2" E

- The village of Leuilly south of Semilly: 49 ° 32 ' N , 3 ° 36' E

- The village of Clacy, southeast of Laon: 49 ° 33 ' N , 3 ° 34' E

- The village of Mons, southwest of Clacy: 49 ° 32 ′ 19.3 ″ N , 3 ° 33 ′ 12.8 ″ E

- The village of Ardon, south of Semilly: 49 ° 32 ′ 54.6 " N , 3 ° 37 ′ 46.6" E

- The village of Athies east of Laon: 49 ° 34 ′ 24 ″ N , 3 ° 40 ′ 58.8 ″ E

- The village of Eppes east of Laon: 49 ° 34 ' N , 3 ° 44' E

- The village of Chambry, northeast of Laon: 49 ° 35 ′ 28.9 " N , 3 ° 39 ′ 18.1" E

- The village of Etouvelles on the Strait of Soissons: 49 ° 31 ' N , 3 ° 35' E

- The village of Chivy north of Etouvelles: 49 ° 32 ' N , 3 ° 35' E

- The village of Chaillevois east of Etouvelles: 49 ° 31 ' N , 3 ° 32' E

- The village of Urcel on the Soissons to Laon road: 49 ° 29 ′ 29.2 ″ N , 3 ° 33 ′ 25.2 ″ E

- The place Festieux on the road from Reims to Laon: 49 ° 31 ′ 20.2 ″ N , 3 ° 45 ′ 11 ″ E

- The village Veslud north of Festieux: 49 ° 32 ' N , 3 ° 44' O

- The place Anizy-le-Château southeast of Laon: 49 ° 30 '23.7 " N , 3 ° 27' 3.9" E

- Soissons on the Aisne: 49 ° 23 ′ N , 3 ° 20 ′ E

- Berry-au-Bac on the Aisne and on the road from Reims to Laon: 49 ° 24 ' N , 3 ° 54' E

- The village of Condé-sur-Suippe near Berry-au-Bac: 49 ° 25 ′ 16.3 ″ N , 3 ° 56 ′ 54 ″ E

Coordinates of the main rivers

- Aisne, flows into the Oise from the left in Compiégne: 49 ° 26 ′ 2.7 ″ N , 2 ° 50 ′ 54.8 ″ E

- Ailette, flows into the Oise from the left: 49 ° 34 ′ 37.2 ″ N , 3 ° 9 ′ 42 ″ E

literature

- Friedrich Saalfeld: General history of the latest time. Since the beginning of the French Revolution . Brockhaus, Leipzig 1819 (4 volumes).

- Karl von Damitz: History of the campaign from 1814 in eastern and northern France to the capture of Paris. As a contribution to recent war history . Mittler, Berlin 1842/43 (3 volumes).

- Friedrich Christoph Förster : History of the liberation wars 1813, 1814, 1815. Volume 2, Verlag G. Hempel, Berlin 1858.

- Ludwig Häusser : German history from the death of Frederick the Great to the establishment of the German Confederation . Salzwasser-Verlag, Paderborn 2012, ISBN 978-3-86382-553-9 (reprint of the Berlin 1863 edition).

- Heinrich Ludwig Beitzke : History of the German wars of freedom in the years 1813 and 1814. Volume 3: The campaign of 1814 in France . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1855.

- Johann Edmund Woerl: History of the wars from 1792 to 1815 . Herder'sche Verlagshandlung, Freiburg / B. 1852.

- Carl von Plotho : The war in Germany and France in the years 1813 and 1814. Part 3, Amelang, Berlin 1817.

- Johann Sporschill: The great chronicle. History of the war of the allied Europe against Napoleon Bonaparte in the years 1813, 1814 and 1815, Volume 2 . Westermann, Braunschweig 1841 (2 volumes)

- Karl von Müffling : On the war history of the years 1813 and 1814. The campaigns of the Silesian army under Field Marshal Blücher. From the end of the armistice to the conquest of Paris . 2nd Edition. Mittler, Berlin 1827.

- Karl von Müffling: From my life. Two parts in one volume . VRZ-Verlag, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-931482-48-0 (reprint of the Berlin 1851 edition).

- Karl Rudolf von Ollech : Carl Friedrich Wilhelm von Reyher , General of the Cavalry and Chief of the General Staff of the Army. A contribution to the history of the army with reference to the Wars of Liberation in 1813, 1814 and 1815. Volume 1, Mittler, Berlin 1861.

- Theodor von Bernhardi : Memories from the life of the kaiserl. Russian Generals von der Toll . Wiegand, Berlin 1858/66 (4 volumes).

- Alexander Iwanowitsch Michailowski-Danilewski : History of the Campaign in France in the Year 1814 . Trotman Books, Cambridge 1992, ISBN 0-946879-53-2 (reprinted from London 1839 edition; translated from Russian by the author).

- Jacques MacDonald : Souvenirs du maréchal Macdonald duc de Tarente . Plon, Paris 1821.

- Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont : Mémoires du duc de Raguse de 1792 à 1832 . Perrotin, Paris 1857 (9 volumes).

- Agathon Fain : Souvenirs de la campagne de France (manuscrit de 1814) . Perrin, Paris 1834.

- Antoine-Henri Jomini : Vie politique et militaire de Napoléon. Racontée par lui-même, au tribunal de César , d ' Alexandre et le Frédéric . Anselin, Paris 1827.

-

Guillaume de Vaudoncourt : Histoire des campagnes de 1814 et 1815 en France . Castel, Paris 1817/26.

- German translation: History of the campaigns of 1814 and 1815 in France . Metzler, Stuttgart 1827/28.

- Alphonse de Beauchamp : Histoire des campagnes de 1814 et de 1815 , 1817

- Frédéric Koch : Mémoires pour servir a l'histoire de la campagne de 1814. Volume 2, Édition Le Normand, Paris 1819.

- Maurice Henri Weil: La campagne de 1814 d'après les documents des archives impériales et royales de la guerre à Vienne. La cavalerie des armées alliées pendant la campagne de 1814 . Baudoin, Paris 1891/96 (4 volumes)

- Henry Houssaye: 1814 (Librairie Académique). 94th edition. Perrin, Paris 1947 (EA Paris 1905).

- German translation: The battles at Caronne and Laon in March 1814. Adapted from the French historical work "1814". Laon 1914.

- Maximilian Thielen: The campaign of the allied armies of Europe in 1814 in France under the supreme command of the Imperial and Royal Field Marshal Prince Carl zu Schwarzenberg . Kk Hofdruckerei, Vienna 1856.

- August Fournier : Napoleon I. A biography . Vollmer, Essen 1996, ISBN 3-88851-186-0 (reprint of the Vienna 1906 edition).

- Archibald Alison : History of Europe from the commencement of the French Revolution to the restoration of the Bourbons in 1815. Volume 11: 1813-1814 . 9th edition. Blackwood, Edinburgh 1860.

- Francis Loraine Petre : Napoleon at Bay. 1814 . Greenhill, London 1994, ISBN 1-85367-163-0 (reprinted by Asug. London 1913).

- David G. Chandler : Campaigns of Napoleon . Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1998, ISBN 0-297-74830-0 (reprint of the London 1966 edition).

- David G. Chandler: Dictionary of the Napoleonic wars . Greenhill, London 1993, ISBN 1-85367-150-9 (EA London 1979).

- Stephen Pope: The Cassell Dictionary of Napoleonic Wars . Cassell, London 1999, ISBN 0-304-35229-2 .

- Gregory Fremont-Barnes: The Napoleonic Wars. Volume 4: The Fall of the French Empire 1813-1815 . Osprey Publ., Oxford 2002, ISBN 1-84176-431-0 .

- François-Guy Hourtoulle: 1814. La campagne de France; l'aigle blessé . Éditions Histoire & Collections, Paris 2005.

- English translation: 1814. The Campaign for France; the wounded eagle . Éditions Histoire & Collections, Paris 2005, ISBN 2-915239-55-X .

Notes and individual references

- ↑ cf. Bernhardie.

- ↑ Today Route National 2 (N2).

- ↑ Today Route National 44 (N44).

- ↑ a b c cf. Petre

- ↑ Houssaye states that Chernyshev lost three quarters of his men.

- ↑ on this section cf. in particular Bernhardie, Sporschil, Damitz, Petre, Beitzke.

- ↑ cf. Sporschil, Damitz, Petre.

- ↑ cf. Mikhailofsky-Danilefsky.

- ↑ cf. Alison

- ↑ In this battle the French general Poret de Morvan was seriously wounded

- ↑ the exact number does not seem to be known.

- ↑ Today Rue de Bruyères

- ↑ There is, however, a handwritten letter from Blücher to his wife dated March 10, 1814 in which he correctly reproduces the events of the previous day.

- ↑ Gneisenau, who never published memoirs himself, is quoted by third parties as saying that he did not believe in a physical illness. See, for example, Häusser.

- ↑ cf. Schürholz: On the mental illnesses of great men

- ↑ cf. Marmont, Houssaye

- ↑ here too the exact number does not seem to be known. But no author gives more than 125.

- ↑ Marmont describes his own losses as minor in his memoirs. There are reasons to assume that he was right and that the Prussians were exaggerating. His corps played a prominent role in the last 20 days of the campaign that it could not have played in the event of heavy losses.

- ↑ The order of the day is given in full by Sporschill and Plotho.

- ↑ Koch says it was already 1:00 a.m.

- ↑ The daily order of Napoleon to his troops can be found in a free translation in Sposchill.

- ↑ These locations are hardly recognizable today.

- ↑ so the troops of the Russian generals Chowansky, Gleboff among others

- ↑ cf. Sporschill and Plotho

- ↑ cf. Sporschil, cook

- ↑ the wording in Blücher's special German was: "old armed men, do not leave the armeh, because we are safe, I am very sick and go myself to the end of the fight, Laon March 12, 1814"

- ↑ cf. Plotho

- ↑ Figures vary from 1,700 to 2,400

- ↑ Coast Guard

Coordinates: 49 ° 33 '56.8 " N , 3 ° 37' 14.1" E