Battle of Fère-Champenoise

| date | March 25, 1814 |

|---|---|

| place | Fère-Champenoise , Marne department |

| output | French troops withdraw |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

|

|

| Troop strength | |

| 19,000 infantry 5,000 cavalry 84 cannons |

12,000 to 20,000 cavalry 48 cannons |

| losses | |

|

5,000 dead and wounded |

2,000 dead and wounded |

Spring campaign 1813

Lüneburg - Möckern - Halle - Großgörschen - Gersdorf - Bautzen - Reichenbach - Nettelnburg - Haynau - Luckau

Autumn campaign 1813

Großbeeren - Katzbach - Dresden - Hagelberg - Kulm - Dennewitz - Göhrde - Altenburg - Wittenberg - Wartenburg - Liebertwolkwitz - Leipzig - Torgau - Hanau - Hochheim - Danzig

Winter campaign 1814

Épinal - Colombey - Brienne - La Rothière - Champaubert - Montmirail - Château-Thierry - Vauchamps - Mormant - Montereau - Bar-sur-Aube - Soissons - Craonne - Laon - Reims - Arcis-sur-Aube - Fère-Champenoise - Saint -Dizier - Claye - Villeparisis - Paris

Summer campaign of 1815

Quatre-Bras - Ligny - Waterloo - Wavre - Paris

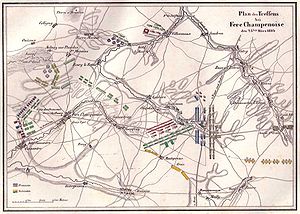

The Battle of Fère-Champenoise was a battle of the Wars of Liberation and took place on March 25, 1814 between French and coalition troops.

The peculiarity of this battle was that on the side of the coalition troops only cavalry and mounted artillery were used.

prehistory

The situation on the part of the coalition forces

On the afternoon of March 23, 1814, Tsar Alexander , the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III. and the commander-in-chief of the coalition troops, Prince Schwarzenberg, jointly decided in a council of war in Pougy not to pursue Napoleon any further, but first to bring about the union with the Silesian army of Blücher . In the next few hours it became known that the closest corps of the Silesian Army under Wintzingerode had already taken Chalons and that his vanguard would soon reach Vitry-le-Francois .

On the evening of March 23, 1813 at 8:00 p.m., the monarchs and Prince Schwarzenberg left Pougy and traveled on to Sompuis , which they reached early in the morning of the next day, March 24, 1814. At 10 a.m. Prince Schwarzenberg and the Prussian King drove on the road to Vitry, while the Tsar stayed behind to consult with his staff. After these deliberations had come to a conclusion, the tsar hurried after those who had gone ahead, whom he caught up around noon. Tsar Alexander now called everyone together for a new council of war in the open air and then suggested that both armies of the coalition troops, the Bohemian Army and the Silesian Army, should move to Paris together in order to bring about the final fall of Napoleon in the French capital. This plan was agreed very quickly and preparations were made immediately to send out the appropriate orders. The Tsar did not hesitate to send instructions to the Russian troops himself.

Bohemian Army

Before dawn of the following day, March 25, 1814, the troops of the Bohemian Army set out to move west from the Marne to Paris. It was a dry day and, as there was little wood in the area, the troops could march across country and keep the paved road clear for the guns and the train. The bulk of the Bohemian Army followed the road from Vitry to Fére-Champenoise . The guards and reserves marched towards Montépreux via Courdemanges and Sompuis .

Silesian Army

The infantry troops of the Silesian Army and some cavalry left Chalons-en-Champagne at 6:00 a.m. and marched along the old road that leads to Paris via Bergerés-les-Vertus and Étoges and Montmirail .

Starting positions of the coalition troops on the morning of March 25, 1814

| commander | origin | division | Branch of service | cavalry | artillery | position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rajewski | Bohemian Army | Peter von der Pahlen | Hussars and Cossacks | 3,500 | 12 | Drouilly , on the left bank of the Marne, oppositeVitry-le-François |

| Bohemian Army | Adam of Württemberg | Hussars | 2,000 | Blacy on the Marne opposite Vitry-le-François | ||

| Barclay de Tolly , Grand Duke Constantine | Russian guards and reserves | Kretow | Cuirassiers | 1,600 | 12 | Maisons-en-Champagne |

| Prince Golitzyn , Duca, Depreradowitsch | Cuirassiers | 1,600 | 12 | Courdemanges | ||

| Oscherowski | Light cavalry | 2,400 | 12 | |||

| Austrian Imperial Guard | Nostitz-Rieneck | Cuirassiers | 2,800 | 18th | ||

| Prussian Guard | Hussars | 800 | 8th | |||

| Seslawin | Bohemian Army | Seslawin | Cossacks | 1,200 | 2 | Pleurs |

| Langeron | Silesian Army | Korff | Light cavalry | 2,200 | 22nd | Chalons-en-Champagne |

| Cossacks | 500 | |||||

| Grekov | Cossacks | 2,700 | ||||

| Sacks | Silesian Army | Vasilchikov | Light cavalry | 1,450 | 12 | |

| Lukovkin | Cossacks | 2,450 | ||||

| Gyulay | Bohemian Army | Hussars | 900 | 6th | Courdemanges | |

| total | 26,400 | 116 |

The situation of the French troops involved

The corps of Marshals Mortier and Marmont

The corps of the French marshals Mortier and Marmont had withdrawn after the battle at Reims via Fismes and Château-Thierry on the Marne, and were constantly pursued by the Prussian corps Yorck and Kleist. On March 22, 1814, both French corps had crossed the Marne. Since they destroyed the Marne Bridge behind them, they gained some distance from the Prussians who followed.

The marshals had received orders from Napoleon to join the army he personally led. Therefore, they marched on to the south-east and reached Etoges on March 23, 1814 . There the two corps separated again. On the evening of March 24, 1814, the Mortier corps was at Vatry and the Marmont corps at Soudé .

In the darkness of the following night, Marmont saw innumerable bivouac fires before him. He sent several officers out to find out whether French or enemy troops were camped there. He skilfully selected these so that they could speak foreign languages and, if necessary, approach foreign troops. All scouts reported on their return of enemy troops, namely Russian and Austrian troops. Marmont immediately sent a courier to Marshal Mortier, who got lost in the dark and did not reach his destination that night.

The Pacthod and Amey divisions

The Pacthod and Amey divisions belonged to the French corps under the command of Marshal MacDonald. They had initially had the task of tracking the reserve artillery of the corps of at least 100 guns, but had lost communication and were in Sézanne on March 23, 1814 . A supply convoy of 80 wagons from Paris had also arrived there with 200,000 rations of bread and plenty of brandy.

The following night it became known that two French corps were at Étoges. The two generals planned to join them and so the train of the two divisions with guns and provisions moved on the morning of March 24, 1814 to Étoges, which had already been abandoned by the corps of Marshals Mortier and Marmont. The troops of Pacthod and Ameys moved on and, exhausted, reached Bergères-lès-Vertus , where they stayed overnight. General Pacthod immediately sent a courier to Marshal Mortier in Vatry. Whatever Mortier issued as an order, it did not reach Pacthod that night, for the courier got lost in the dark and did not find his troops again until the next morning.

Starting positions of the French troops on the morning of March 25, 1814

| commander | division | Foot troops | cavalry | artillery | position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortier | Christiani | 2,220 | 10 | Vatry | |

| Curial | 2,700 | 10 | Vatry | ||

| Charpentier | 2,260 | 10 | Vatry | ||

| Roussel under Belliard | 1,500 | Bussy-Letrée | |||

| Ghigny under Belliard | 550 | Vatry | |||

| Marmont | Ricard | 880 | 12 | Soudé | |

| Lagrange | 2,200 | 14th | Soudé | ||

| Arrighi | 1,820 | 12 | Soudé | ||

| Bordesoulle | 1,300 | Cool ones | |||

| Merlin | 1,000 | Soudé | |||

| Pacthod | Pacthod | 4,000 | 100 | 12 | Bergères-lès-Vertus |

| Amey | 1,800 | 6th | Bergères-lès-Vertus | ||

| Compans | Noizet | 800 | 800 | at Sézanne (only 400 riders take part in the battle) | |

| Vincent | 800 | 800 | at Montmirail (does not take part in the battle) | ||

| total | 18,880 | 5,350 | 86 |

Course of battle

The battle of the French corps Mortier and Marmont

historical painting from 1891, Bogdan Pawlowitsch Willewalde (1818–1903)

First battle at Soudé

At 3:00 a.m. on March 25, 1814, the cavalry of the Württemberg corps and the Russian Rajewski corps, as the avant-garde of the Bohemian Army, began their march westward on Paris. They set out from the left bank of the Marne at Vitry-le-Francois . The Russian horsemen were under the command of Count von Pahlen , the Württemberg riders under the command of Prince Adam of Württemberg . With them was Crown Prince Wilhelm von Württemberg , who, as the tsar's cousin, held a prominent position and to whom the supreme command of both corps had been transferred. Their way led them directly to Soudé , where the French Corps Marmont still stood.

At 5:00 in the morning, Marshal Mortier personally, coming from Vatry, arrived at Marmont with a small company and without his troops. The two marshals quickly agreed to establish a common position backwards at Sommesous . Mortier immediately returned to his troops to lead them to the agreed location.

When the advance guard of the Bohemian Army reached Soudé at 8:00 a.m., they were fired at from numerous artillery pieces from the Marmont Corps, which had been in battle behind the town. The coalition troops had only 12 guns from a mounted battery with which they could return fire. But their riders immediately tried to encircle the French corps: the Russians from the north, the Württemberg from the south. French cuirassiers under Bordesoulle rode towards them, but could not hold their own. Marmont ordered his troops to move westwards on the road to Sommesous in firm order. Some rifle companies that remained in Soudé to repel the pursuers were surrounded by coalition troops and later had to surrender.

Artillery duel at Sommesous

At Sommesous, Marmont's troops lined up south of the town: the infantry in Karrées, with cavalry and artillery in front of them. Their guns - 30 in number - immediately began their defensive fire against the following riders of the coalition troops. When the Corps Mortier arrived from Vatry, it took up position north of the village and the number of guns firing on Russians and Austrians increased to 60. At this point the French troops outnumbered those of the coalition. In the distance, however, the mass of the Bohemian army could be seen and the marshals knew that they would not be able to stay here long. Their position was also unfavorable in that both corps were separated by the course of the La Somme stream .

The coalition troops were initially prevented from advancing by the Soudé brook, which riders and artillery had to overcome. But they soon brought together 36 light guns with which they returned fire from the French. This artillery duel lasted 2 hours. Meanwhile, Mortier's troops were able to cross the dividing brook and both corps took up a common position between Montépreux and Haussimont . The infantry, lined up in Karrées, faced southeast, the cavalry behind them.

Soon afterwards, 2,500 Austrian guard cuirassiers under Count Nostiz arrived at Sommesous. The French marshals now decided to go further back along the road to Fère-Champenoise, 17 kilometers away. When the French guns were about to be revamped, unrest arose due to the fact that the Corps Mortier used stallions to pull the guns. The Russian hussars Count Pahlens took the opportunity and attacked the cuirassiers Bordesoulles and drove them apart. The Roussel d'Hurbals dragoons accompanying Mortier's corps came to the aid of the French cuirassiers, but were then attacked in turn by Count Pahlen's Cossacks and initially fled in panic, but soon rallied again. At the same time, Württemberg mounted hunters and Austrian hussars attempted an attack from the south, but were repulsed by French Uhlans and a strong artillery fire. In total, the French lost 5 guns when they set off.

It was 2 p.m. when the weather turned and a violent easterly storm began to blow, driving wind, snow and hail across the battlefield. The French infantry could no longer load or fire their muskets and only had to defend themselves with the bayonet.

The leadership of the coalition troops used the time to bring the available forces of the Russian guard cavalry from Sompuis via Poivres . In the storm, the Russian Guard Cuirassier Division under Depreradowitsch, the light Russian Guard Cavalry under Oscherowski, the Russian Guard Uhlans, a regiment of Guard Dragoons and a battery of mounted Guard Artillery - altogether more than 3,000 horsemen - intervened and intervened immediately into the fighting. The guard cuirassiers managed to blow up two French squares and routed a battalion of the Mortier Corps.

The Württemberg hunters also managed to blow up one of the squares in the fourth attack with the support of Austrian hussars.

Passing through Connantray

The Frenchman moved the direct route to Fère-Champenoise from the Vaure-Bach. It rises south of the road from Sommesous to Fère-Champenoise and then flows deeply into the terrain in an arc that extends north to Fère-Champenoise. The only bridge was at the entrance to Connantray . When the French corps got there after 12 kilometers, they had to disband the Karrées in order to be able to cross the place. They got into disarray and many units gave up their guns: The next day 24 abandoned guns and more than 60 ammunition wagons were found in Connantray. In a short time, the small place was completely clogged. The veterans of the Ricard and Christiani divisions were best at keeping order and keeping the enemy cavalry at bay.

When Connantray had become impassable, the last French units could no longer cross the Vaure brook and had to go back on the right bank of the brook following its course. They kept order in this and were hardly persecuted. Behind Fère-Champenoise they met again with the remnants of their corps.

Several regiments of the Young Guard and a French twelve-pounder battery had held a position in front of Connantry and tried to cover the retreat of the French. They were surrounded and many of them fell in battle. The rest were captured with General Jamin .

Partial flight and retreat of the French

Since Connantray was completely clogged, the coalition forces could not cross the Vaure brook there. A transition for the tabs was only found after some searching. Around this time 1,200 Cossacks under Seslawin approached the fighting from the south-west on the Euvy route . When the French cavalry saw that enemy riders were approaching from two directions, they believed they were surrounded; Panic broke out: first the French cavalry fled on the road to Fère-Champenoise, then followed the infantry, which saw themselves left defenseless to the enemy. Quite a few of the French ran as far as Meaux, which is 100 kilometers away, before they accepted the forces of the General Compans. During this escape, the French abandoned another 40 guns and a large number of ammunition and transport wagons.

The marshals were initially carried away by the general escape and were only able to collect the remnants of their crews at the Linthes level and position them between Saint Loup and Broussy-le-Grand . A few hundred French cuirassiers who did not belong to this French corps and who came from Sézanne at 5 p.m. followed the noise of the battle and fearlessly and in the best order against the multiple superiority of the enemy cavalry, saved the French corps from complete destruction.

Marshal Marmont led the French back to Allemant . In the early evening in the dark, the coalition riders left the chase and withdrew.

The fall of the Pacthod and Amey divisions

First pursuit by cavalry of the Silesian Army

The Pacthod and Amey divisions interrupted their train from Bérgeres to Vatry on the morning of March 25, 1814 at 10.30 a.m. at Villeseneux to rest. The French soldiers began to cook themselves a meal and they fed the horses of the teams.

At the same time, the Silesian Army moved from Chalons-en-Champagne to Bérgeres. Their vanguard was formed by the cavalry of Sacken Corps under Vasilchikov . The Chief of Staff of the Silesian Army Gneisenau , who represented the sick Field Marshal Blücher , had ordered a survey to the south, in which he personally participated. During this investigation, the train of the French divisions was noticed. General Korf was sent out with the light cavalry of the Langeron Corps , several Cossack groups under Karpov and a mounted battery to provide them. They branched off the road at Thibie and marched in the direction of Germinon . In Germinion everyone used the tiny bridge over the Soude brook, which stretched their formation far apart.

When the French saw the approaching coalition troops, they positioned themselves north of Villeseneux. The Pacthod division stood in rows, the Amey division on the left wing in the square. The guns were in front of it, the baggage train had been brought to the rear. In this position they were well protected by their strong artillery and the Russian cavalry did not yet dare a single attack, only single actions. The Cossacks attacked the train from which they expected good booty. Around noon, Pacthod and Amey decided to retreat to Fère-Champenoise via Clamanges, following the course of the Somme stream .

A futile retreat to Fère-Champenoise

The French formed six squares, which included the entourage and marched very slowly towards Fère-Champenoise, 15.5 kilometers away. In doing so, they made sure to use every possible cover and always have some guns ready to fire. The enemy Russian artillery fired from only 4 guns, but from less than three hundred meters away. More cavalry from the Langeron Corps arrived at Clamanges. This almost doubled the number of Russian riders. The French generals therefore decided to give up the wagons of the entourage and the entrusted supplies, but not the guns. The released horses were used to double-harness as many guns as possible. The French Karrées continued to move towards Fère-Champenoise at an accelerated pace. Some of their men who occupied Clamanges were left to their fate. None of these could escape the Russians.

Around 2 p.m., 2,500 more horsemen of the Sacken Corps of the Silesian Army under Vasilchikov - including four regiments of dragoons - arrived at Ecury-le-Repos . They had come from Bergères via Moraines. The French divisions were now surrounded by about 5,000 enemy horsemen. The Russian cavalry now attacked resolutely from all sides, but were stopped by the fire of the French, which they only released from 100 meters. Two Russian dragoon regiments with several guns tried to relocate the French Karrées. Once again the French made the breakthrough on the road to Fère-Champenoise with a quickly formed column, but after less than two kilometers they were caught and trapped again. Yet the French did not surrender. In closed squares, they tried to move on towards Fère-Champenoise.

At that time, two mounted batteries of the Sacken Corps of the Silesian Army arrived. This changed the situation of the French to their disadvantage: as soon as these guns came into action, their losses increased dramatically.

The Russian cuirassiers of the Bohemian Army under Kretov arrived to strengthen the coalition troops. But the French did not surrender. Within sight of Fère-Champenoise they saw a large number of troops there and the hope arose that these would be the French corps under Mortier and Marmont, with whom one could now connect. But they were Russian troops, with the Tsar and the Prussian King in person. The Russians immediately brought more guns into position and opened fire on the approaching French. Some of the projectiles were aimed too far and hit the Russian hussars Vasilchikov, whose light batteries returned fire. An adjutant of the tsar had to intervene to clear up the error.

Tsar Alexander I and the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III. had left Vitry at 10 a.m. and followed their troops and the noise of the battle. In the late afternoon they had just left Fère-Champenoise when a courier from General Kretow brought in the news that they were engaged in combat with other French troops. Couriers were sent out immediately to bring all coalition troops in the area together for battle.

Escape to the marshes of the Petit Morin

Fère-Champenoise was no longer accessible for the French, so Pacthod decided to try to escape north into the marshes of the Petit Morin , which they would have reached after 7 kilometers between Morains and Bannes and in which the enemy cavalry would no longer follow them can. Of the six squares of the French there were four left, which were now slowly escaping north. Gradually more and more coalition cavalry units arrived, especially those who had followed the corps of Marshals Mortier and Marmont during the day and were now leaving them. Most recently, up to 20,000 riders surrounded the French Karrées. The coalition troops also continued to strengthen their artillery: Soon there were 48 guns that fired from a short distance at the French, whose order was now weakening.

Count Wilhelm von Schwerin from Blücher's staff reports on this situation:

“The Pacthod division stubbornly disdained any surrender. Enclosed on all sides by an enormous superior force, huddled together to certain death, the desperate heroes formed a square which served as a target for all the artillery set against them and was shot down by them. A hideous massacre began ... "

The Prussian king sent one of his officers to General Pacthod as a parliamentarian, who raised his voice to urge him to resign because his situation was hopeless. Pacthod had him arrested and called to his troops:

“You heard what to expect. Voilà - a great day for France "

Of the French Karées, three remained, who almost managed to escape into the swamps. But before Morains the Russians had set up some artillery across the road, the fire of which brought the French to a halt. Now Pacthod, wounded several times himself, was ready to surrender. Two of the remaining French Karrées also laid down their weapons. Only the last square did not surrender. When the mass of the enemy attacked this, 500 French managed to escape into the swamps.

Eyewitnesses reported that not a few of the French recruits who had to fight that day were not wearing uniforms. She had been sent out to Paris to take a uniform from a dead or wounded man. Many will not have had a gun or could not handle it.

The days after

French corps move west

On the night of March 26, 1814, Marshal Marmont sent a courier to Sézanne, 20 kilometers away, to the French General Compans, who had gathered all sorts of scattered French troops there. But this was already on the march to the west and had evacuated the city at 2 a.m. Around this time the corps of Marshals Mortier and Marmont set out west, lost a few hours fighting their way through Sézanne, which had already been penetrated by Prussian troops, and reached Esternay at noon , where they were at the height of Retourneloup paused.

Here they learned that the advance guard of the Prussian Corps Yorck from Château-Thierry and Montmirail had already reached and occupied La Ferté-Gaucher . Later Count Pahlen attacked the rearguard of the Marmont Corps with the vanguard of the Russian Corps Rajewski .

The two French corps now divided: the Marmont corps turned backwards against the Russian cavalry Pahlens while the Mortier corps advanced against the Prussians in La Ferté-Gaucher. Mortier's men did not succeed in asserting themselves against the Prussians and occupying the place. Mortier therefore thought it too dangerous to march further west with the Prussians at his back, and decided to move south to Provins . Marmont saw no other choice for himself and his corps than to join this direction. The French marched all night and reached Provins the next morning of March 27, 1814.

After a day of rest, both corps marched to Nangis and from there on various routes to Paris. On the afternoon of March 29, 1814, they met again at the Charenton Bridge , and on March 30, 1814, they played an essential role in the defense of Paris .

Persecution by Prussian troops

The Prussian Generals Yorck and Kleist had arrived in Montmirail with the reserve cavalry of their two corps on the evening of March 24, 1814, from Château-Thierry . The next day, March 25th, 1814, the bulk of the corps followed on a bad road via Viffort , which took them almost the whole day.

Battle of Sézanne on March 26, 1814

The reserve cavalry of both corps under Zieten advanced meanwhile and reached Étoges around noon , where the horses had to be fed. There one could hear the noise of the battle and around 3 p.m. Zieten rode south with his riders. When they reached Fère-Champenoise in the late afternoon, the fighting was over. Zieten then decided to move on to Sézanne that night in order to field the French. At 4 a.m. on March 26, 1814, the Prussians reached Sezanne. The advance guard of the French corps Mortier and Marmont reached the area in the dark of night. At first it was exclusively French cavalry under Belliard, which got into individual small skirmishes with the Prussians in and around Sézanne. When French infantry came up, the Prussians could no longer hold out and had to withdraw. They withdrew via Tréfols to Meilleray , which they reached late in the evening.

Battle at Ferté-Gaucher on March 26, 1814

On the morning of March 26, 1814, the two Prussian generals Yorck and Kleist had their corps march from Montmirail to La Ferté-Gaucher , 20 kilometers away . The roads were soft and very bad, and the teams made slow progress. The artillery in particular had great problems advancing their guns.

La Ferté-Gaucher lies in the valley of the Grand Morin on its northern bank. The road from Sézanne to Meaux leads past the city on the opposite south bank. That morning, Ferté-Gaucher was occupied by about 1,000 French. On the road on the opposite bank, a strong convoy of wagons moved west. These were the General Compan's crews who had left Sézanne that night and were on their way to retreat to Paris via Meaux.

Yorck personally arrived in front of the city at 10 a.m. When the French discovered the Prussians, they immediately set out to withdraw west. Yorck sent the division under Horn after them, which was the first to arrive from Montmirail, and gave them all the riders that were available at the time.

The next Prussian division to arrive before Ferté-Gaucher was under the command of the Prussian Prince Wilhelm , the youngest brother of the Prussian king. This division was only 3,800 strong. Soon afterwards it became clear that further infantry would not arrive until further notice, as unfortunately the entourage had pushed itself between the two corps and could not be overtaken on the bad roads. Only the reserve artillery arrived before the train.

At around 2 p.m. the first troops of the French Mortier corps appeared on the Strait of Sézanne, and at around 4 p.m. the whole corps was assembled in front of Ferté-Gaucher. The Prussians had drawn the consequences of their numerical inferiority and withdrew to the north bank of the Grand Morin . From there their artillery dominated the street across the river. The town itself was occupied by three regiments of infantry. At around 6 p.m. the French advanced to attack the city. When they reached the level of Maison Dieu , the Prussian artillery opened fire on the opposite side of the river. In no time at all, the French got into disarray and their attack collapsed. Marshal Mortier had his men move south and regrouped at Chartronges . Obviously, he did not trust his teams, who were badly battered from the previous day, to make an energetic and successful attack. When the Prussian corps Kleist arrived and positioned its artillery south of the river, the French withdrew on the road to Provins .

Skirmish at Chailly on March 26, 1814

The Prussian Horn Division pursued the French troops under Compans on the road from La Ferté-Gaucher to Coulommiers . During the march through the village of Chailly , the French came to a standstill, which the Prussian cavalry used to attack. It drove the French out of town and dispersed them on the terrain beyond. In front of Coulommiers, the French rallied again and brought some guns to use. The Prussian horsemen had no artillery with them and had to wait two hours for them to arrive. By then, the majority of the French had withdrawn and left the city and the bridge over the Grand Morin to the Prussians . The Prussians claimed to have taken 400 prisoners in this battle.

literature

- Friedrich Saalfeld: General history of the latest time. Since the beginning of the French Revolution . Brockhaus, Leipzig 1819 (4 vol.).

- Karl von Damitz: History of the campaign from 1814 in eastern and northern France to the capture of Paris. As a contribution to recent war history . Mittler, Berlin 1842/43 (3 vol.).

- Friedrich Christoph Förster : History of the Wars of Liberation 1813, 1814, 1815, Vol. 2 . G. Hempel, Berlin 1858.

- Ludwig Häusser : German history from the death of Frederick the Great to the establishment of the German Confederation . Salzwasser-Verlag, Paderborn 2012, ISBN 978-3-86382-553-9 (reprint of the Berlin 1863 edition).

- Heinrich Ludwig Beitzke : History of the German wars of freedom in the years 1813 and 1814, Vol. 3: The campaign of 1814 in France . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1855.

- Joseph Edmund Woerl: History of the wars from 1792 to 1815. Herder'sche Verlagshandlung, Freiburg / B. 1852.

- Carl von Plotho : The war in Germany and France in the years 1813 and 1814, part 3 . Amelang, Berlin 1817.

- Johann Sporschill: The great chronicle. History of the war of the allied Europe against Napoleon Bonaparte in the years 1813, 1814 and 1815, vol. 2 . Westermann, Braunschweig 1841 (2 vol.).

- Karl von Müffling : On the war history of the years 1813 and 1814. The campaigns of the Silesian army under Field Marshal Blücher. From the end of the armistice to the conquest of Paris . 2nd Edition. Mittler, Berlin 1827.

- Karl von Müffling: From my life. Two parts in one volume . VRZ-Verlag, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-931482-48-0 (reprint of the Berlin 1851 edition).

- Karl Rudolf von Ollech : Carl Friedrich Wilhelm von Reyher , General of the Cavalry and Chief of the General Staff of the Army. A contribution to the history of the army with reference to the wars of liberation of 1813, 1814 and 1815, vol. 1 . Mittler, Berlin 1861.

- Friedrich Rudolf von Rothenburg (ed.): The battles of the Prussians and their allies from 1741 to 1815. Melchior-Verlag, Wolffenbüttel 2006, ISBN 3-939791-12-1 (reprint of the Berlin 1847 edition).

- Theodor von Bernhardi : Memories from the life of the kaiserl. Russian Generals von der Toll . Wiegand, Berlin 1858/66 (4 vol.).

- Alexander Iwanowitsch Michailowski-Danilewski : History of the Campaign in France in the Year 1814 . Trotman Books, Cambridge 1992, ISBN 0-946879-53-2 (reprinted from London 1839 edition; translated from Russian by the author).

- Modest Iwanowitsch Bogdanowitsch : History of the war in France in 1814 and the fall of Napoleon I .; according to the most reliable sources , Schlicke-Verlag, Leipzig 1866 (2 vols.).

- John Fane, 11th Earl of Westmorland: Memoirs of the operations of the allied armies under Prince Schwarzenberg and Marshall Blucher during the latter end of 1813 and the year 1814 . Murray, London 1822 (2 vols.).

- German translation: Memoirs on the operations of the allied armies under Prince Schwarzenberg and Field Marshal Blücher during the end of 1813 and 1814 . Mittler, Berlin 1844.

- Jacques MacDonald : Souvenirs du maréchal Macdonald duc de Tarente. Plon, Paris 1821.

- Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont : Mémoires du duc de Raguse de 1792 à 1832 . Perrotin, Paris 1857 (9 vols.).

- Agathon Fain : Souvenirs de la campagne de France (manuscrit de 1814) . Perrin, Paris 1834.

- Antoine-Henri Jomini : Vie politique et militaire de Napoleon. Racontée par lui-même, au tribunal de César , d ' Alexandre et de Frédéric . Anselin, Paris 1827.

-

Guillaume de Vaudoncourt : Histoire des campagnes de 1814 et 1815 en France. Castel, Paris 1817/26.

- German translation: History of the campaigns of 1814 and 1815 in France . Metzler, Stuttgart 1827/28.

- Alphonse de Beauchamp : Histoire des campagnes de 1814 et de 1815, Vol. 2 . Édition Le Normand, Paris 1817.

- Frédéric Koch: Memories pour servir a l'histoire de la campagne de 1814. Accompagnés de plans, d'ordres de bataille et de situations. Maginet, Paris 1819.

- Maurice Henri Weil: La campagne de 1814 d'après les documents des archives impériales et royales de la guerre à Vienne. La cavalerie des armées alliées pendant la campagne de 1814. Baudouin, Paris 1891/96 (4 vol.).

- Alexandre Andrault de Langeron : Memoires de Langeron. General D'Infanterie Dans L'Arme Russe. Campagnes de 1812, 1813, 1814. 1923.

- Henry Houssaye: 1814 (Librairie Académique). Perrin, Paris 1905.

- German translation: The battles at Caronne and Laon in March 1814. Adapted from the French historical work "1814" . Laon 1914.

- Maximilian Thielen: The campaign of the allied armies of Europe in 1814 in France under the supreme command of the Imperial and Royal Field Marshal Prince Carl zu Schwarzenberg . Kk Hofdruckerei, Vienna 1856.

- August Fournier : Napoleon I. A biography . Vollmer, Essen 1996, ISBN 3-88851-186-0 (reprint of the Vienna 1906 edition).

- Archibald Alison : History of Europe from the commencement of the French Revolution to the restoration of the Bourbons in 1815, Vol. 11: 1813-1814 . 9th edition. Blackwood, Edinburgh 1860.

- Francis Loraine Petre: Napoleon at Bay. 1814. Greenhill, London 1994, ISBN 1-85367-163-0 (reprint of the London 1913 edition).

- David G. Chandler : Campaigns of Napoleon. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1998, ISBN 0-297-74830-0 (reprint of the London 1966 edition).

- David Chandler: Dictionary of the Napoleonic wars. Greenhill, London 1993, ISBN 1-85367-150-9 (EA London 1979).

- Stephen Pope: The Cassell Dictionary of Napoleonic Wars. Cassell, London 1999, ISBN 0-304-35229-2 .

- Gregory Fremont-Barnes: The Napoleonic Wars, Vol. 4: The Fall of the French Empire 1813-1815. Osprey Publ., London 2002, ISBN 1-84176-431-0 .

- François-Guy Hourtoulle: 1814. La Campagne de France; l'aigle blessé . Éditions Histoire & Collections, Paris 2005.

- English translation: 1814. The Campaign for France; the wounded eagle . Éditions Histoire & Collections, Paris 2005, ISBN 2-915239-55-X .

- Michael V. Leggiere: The Fall of Napoleon, Vol. 1: The Allied Invasion of France 1813-1814. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-87542-4 .

- Andrew Uffindell: Napoleon 1814. The Defense of France. Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley 2009, ISBN 978-1-84415-922-2 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e the information is mainly taken from the French literature Vaudoncourt, Koch and, as far as possible, has been compared with Damitz, Sporschill and Bogdanowitsch. The information in different literature sources often deviate considerably from one another.

- ^ Hans-Peter Müller, Jürgen Wittlinger: Napoleon against Europe, 2008, p. 219.

- ↑ a b here only the guns are counted that were used in combat

- ↑ All Empires: The Battle of La Fère-Champenoise, 1814

- ↑ previously also Sommepuis

- ↑ Most of the cavalry of the Wintzingerode Corps was assigned to watch the French army under Napoleon

- ↑ cf. on this Sporschill

- ↑ Prince Golitzyn was the commander of the Russian guard cuirassiers

- ↑ Ghigny was a colonel in the Roussel cavalry corps, the other officers with the rank of colonel were Christophe and Leclerc

- ↑ cf. Houssaye, Bogdanowitsch and Damitz

- ↑ a b c d e cf. on this, Houssaye

- ↑ cf. Bogdanowitsch, Damitz, cook

- ↑ a b c d cf. on this Damitz

- ↑ cf. Houssaye, Bogdanowitsch, Koch and Alison, chap. LXXV

- ↑ Such a mass panic was not unique: When the Marmont Corps attacked the bivouacking Russians and Prussians in Étoges on February 14, 1814, in panic, they ran 40 kilometers to Chalons-en-Champagne that night

- ↑ cf. Marmont, 20th book

- ↑ cf. Houssaye, Damitz

- ↑ The presentation of this section of the battle at Bogdanowitsch differs from the representations of other authors

- ↑ Houssaye says it was already 4:00 p.m.

- ↑ from Liberation 1813 1814 1815, documents reports letters , Munich 1913.

- ↑ Amey was not wounded

- ↑ Damitz denies that the French managed to escape.