Battle of Paris

| date | March 30, 1814 |

|---|---|

| place |

Paris , France |

| output | Coalition victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 25,000 men | 80,000 men |

| losses | |

|

4,000 dead and wounded |

8,200 dead and wounded |

Spring campaign 1813

Lüneburg - Möckern - Halle - Großgörschen - Gersdorf - Bautzen - Reichenbach - Nettelnburg - Haynau - Luckau

Autumn campaign 1813

Großbeeren - Katzbach - Dresden - Hagelberg - Kulm - Dennewitz - Göhrde - Altenburg - Wittenberg - Wartenburg - Liebertwolkwitz - Leipzig - Torgau - Hanau - Hochheim - Danzig

Winter campaign 1814

Épinal - Colombey - Brienne - La Rothière - Champaubert - Montmirail - Château-Thierry - Vauchamps - Mormant - Montereau - Bar-sur-Aube - Soissons - Craonne - Laon - Reims - Arcis-sur-Aube - Fère-Champenoise - Saint -Dizier - Claye - Villeparisis - Paris

Summer campaign of 1815

Quatre-Bras - Ligny - Waterloo - Wavre - Paris

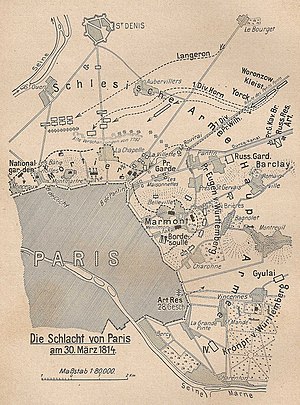

The Battle of Paris , also known as the Battle of Montmartre , took place on March 30, 1814 east of Paris. It was the last battle of the winter campaign of 1814 , but not the last battle of the Napoleonic Wars . As a result, it led to the occupation of Paris by the coalition army on March 31, 1814 and Napoleon's abdication .

prehistory

After the Battle of Arcis-sur-Aube on March 20 and 21, 1814, the Bohemian Army of the coalition forces pursued their opponents north to Vitry-le-François . There it came to a battle with parts of the French rearguard on March 23, 1814, which was successfully waged by the coalition troops. They captured 22 guns and took 500 prisoners. But Napoleon sat down with the bulk of his troops further east to Saint-Dizier from.

Emperor Franz II of Austria went to Dijon with his companion, who was also Prince Metternich , giving his Commander-in-Chief Schwarzenberg a free hand for the next operations. Tsar Alexander I and his close personal friend and political shadow, the King of Prussia Friedrich Wilhelm III. , stayed with the Bohemian Army.

The coalition troops, now standing between Paris and the Napoleonic troops , succeeded in intercepting several couriers, both those who had been sent to Napoleon from Paris and those who were traveling in the opposite direction. On March 23, 1814, a courier was arrested who was carrying a personal letter from Napoleon to his wife Marie-Louise , the daughter of Franz II of Austria. In this letter, Napoleon openly revealed his intentions and wrote: "I have decided to approach the Marne and its surroundings in order to withdraw them [the Bohemian Army] from Paris". With this, the leadership of the coalition forces knew that Napoleon had no intention of covering Paris.

Tsar Alexander learned of the contents of this letter on March 24, 1814 and then called his marshals together for a consultation. It was agreed to take this opportunity and move west to take Paris. In this sense, the King of Prussia and the Commander-in-Chief, Prince Schwarzenberg, were informed. Both agreed without reservation, and the order was issued to both coalition armies , the Silesian Army under Blücher and the Bohemian Army under Schwarzenberg, to march west and unite before Paris.

Schwarzenberg assigned the cavalry and mounted artillery of the Wintzingerode Corps to follow Napoleon and cover the coalition armies to the east. The French army moved as far as the Wassy area south of Saint-Dizier. Napoleon was firmly convinced that the cavalry that followed him was the vanguard of the Bohemian army. In order to force them to battle, he returned to Saint-Dizier on March 26th and provided Wintzingerode's troops in the so-called battle at Saint-Dizier . Wintzingerode's riders suffered considerable losses and had to retreat north to Bar-le-Duc .

On March 25, the Bohemian Army set out on Paris and met the Marmont Corps and the Young Guard under Mortier , who in turn moved east and had orders to unite with the Napoleonic troops at Saint-Dizier. The battle of Fère-Champenoise developed , in which the French troops were defeated and pushed west onto Paris. As a result, they arrived in time to defend Paris, and it was precisely the remnants of these two corps that made up the bulk of the men who bloody defended Paris on March 30, 1814.

On the night of March 26-27, 1814, troops of the Silesian Army captured 2000 French soldiers in a night battle near La Ferté-sous-Jouarre on the Marne. The following day another 10,000 French tried to stop the Silesian Army between La Ferté-sous-Jouarre and Meaux , but were driven out by Prussian troops under Horn . At Claye-Souilly, Mortier's corps was attacked by Prussian troops under Yorck and driven back further. The Russian corps Rajewski reached Bondy that day .

On March 28, 1814, the first corps of the Silesian Army stood in front of Paris, but had to wait a day there to wait for the bulk of the Bohemian Army, especially the Russian Guard. This one day delay was enough for the French corps under Marmont and Mortier to reach Paris on March 29, 1814 before the coalition troops and to organize the defense of Paris.

On March 29, 1814, Napoleon's wife Marie-Louise left Paris at 10:00 a.m. and went with the ministers devoted to Napoleon to Blois just before Tours on the Loire . 1,500 guardsmen accompanied them and were then absent from the defense of Paris. In Paris remained Talleyrand and Napoleon's eldest brother Joseph Bonaparte , former King of Naples and Spain and is currently represented by Napoleon in Paris. He tried to strengthen the will to resist by sending a proclamation to the citizens of Paris. He later set up his headquarters on Montmartre, but did not have any influence on the military events until his escape.

Topography of the battlefield

The battle of March 30, 1814 took place in the area east and north of Paris from the inflow of the Seine into the urban area in the southeast to the outflow of the Seine in the north. This area is now completely built up to the Belleville Park and belongs either to Paris or to one of its suburbs. In 1814 the area was already heavily built up and offered the defenders many opportunities to find cover.

In the south of the battlefield are the park and castle Vincennes with the partly fortress-like facilities of the castle of Vincennes . To the north there is a hilly landscape with the hill of Belleville, which drops steeply and partly rocky to the north towards flat land. Just to the north flows the Canal de l'Ourcq , which then and now supplies Paris with water and ends in the La Villette basin immediately before the Barriere de Pantin . This canal divides the battlefield into two parts and could only be crossed in 1814 at the eastern town of Pantin , which at that time was still a village. North of the Barriere de Pantin is the suburb of La Villette . Montmartre rises further to the west, north of the city.

By far the most violent fighting occurred in the triangle bounded by the Canal de l'Ourcq in the north, the edge of the hills at Belleville in the south and Pantin in the east. The western tip of this triangle was the Barriere de Pantin with its gateway to the city. In this area the coalition forces suffered half of their considerable losses.

The preparations of the defenders

In Paris there was no garrison in 1814 , so that only a small number of troops from the area could be used for defense, around 6,000 men. However, an unknown, but not small, number of volunteers and veterans joined the regular troops. The bridge at Charenton was defended by veterans and students from the École Vétérinaire de Maisons-Alfort (École nationale vétérinaire d'Alfort), 150 of whom fell in a single attack by the Austrians. Two batteries (28 guns) of the artillery reserve near the small fort of Vincennes were to serve the students of the École polytechnique . However, they lost the guns after the first attack by the Württembergians .

The fact that the magazines in Paris were abundantly filled with war implements was very important for the defenders: a large number of guns and ammunition were available. Since Marshal Marmont was a trained artilleryman, he knew how to position these guns cheaply and still well covered in a short time. The triangle of terrain just described west of Pantin was swept from three sides by French artillery. It was estimated that Marmont managed to bring 140 guns (10 batteries) out of Paris into battle. Napoleon later claimed that Paris had more than 200 guns and an enormous supply of ammunition.

The French troops had divided the area: the Marmont corps defended south of the Canal de l'Ourcq, Mortier commanded north of it. In the far north, west of Montmartre, the newly created National Guard positioned itself. It was possible, however, for units to move through the city from one side to the other.

The course of the battle

The morning until 11:00

It was not the first time that Schwarzenberg's orders of the day were finished very late on the evening of March 29, 1814. They were not handed over to the couriers until 11 p.m. In the dark of night, they had to search for the commanders to whom they were addressed in unknown terrain. Some units did not receive their orders for March 30th until the early morning, at a time when they should have been ready for action. As a result, the corps of the Silesian Army in the north arrived at least four hours late and the corps of Crown Prince Wilhelm of Württemberg went into action in the south much later.

The only coalition troops advancing from the east at exactly 6:00 a.m. were the Russian corps under Rajewski and behind them the Russian guard under Barclay de Tolly . Pantin was taken against the first French resistance until 7:00 a.m., but the attempt to take the unoccupied Romainville, which was further to the east, but also higher up, before the French, initially failed. Only after hours of fighting could Romainville be occupied with the support of Russian grenadiers around 10:00 a.m. No further progress was made until 11:00 a.m., on the contrary, both villages threatened to be lost again under the action of French artillery, which constantly inflicted losses on the coalition troops.

At 10:00 a.m. the advance guard of the Silesian Army reached the area north of the Canal de l'Ourcq in front of La Villette and was able to deliver some troops over the canal bridge to support Pantin.

Midday from 11:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m.

At 11:00 by Marshall were sent Barclay de Tolly following commands: The first Russian Grenadier Division should proceed on Romainville addition to Belleville, the second Russian Grenadier Division to the heights of Romainville and Montreuil occupy, north of the Bois de Vincennes, and the Prussian Guard under Colonel Alvensleben was supposed to support the troops in Pantin. The Russian Guard was held back as a reserve.

The Prussian guards, who had not been in action since May 2, 1813, the battle of Großgörschen , arrived in Pantin at around 12:00 p.m. The staff officers of the Russian division, who held Pantin at the time, warned Colonel Alvensleben of the cul-de-sac (dead end) between Pantin and the Barriere de Pantin, which could be shot at by French artillery from three sides. Despite the warning, Colonel Alvensleben sent two battalions there. The French troops took cover behind the scattered homesteads and houses of Les Maisonette and their artillery, predictably, fired on the Prussians from three sides. The Prussians tried to escape, but of 1,800 guardsmen who had advanced, only 150 came back to Pantin. Colonel Alvensleben immediately sent the next guardsmen to the cul-de-sac, but this time twice that number, four battalions. These also went ahead uncovered and were fired at 80 paces from the French guns in front of the Barriere de Pantin. That was too short; some guardsmen succeeded in overcoming the distance and seized the guns, a whole battery (14 guns), and silenced them. But the unabated shelling from the south and north remained, which in turn forced the guardsmen to seek cover in the surrounding houses and farms. They were stuck there for another three hours, while their numbers were reduced by the effects of the artillery fire. These actions by the Prussians between 12:00 p.m. and 2:00 p.m. contributed a quarter to the total losses of the coalition troops, without influencing the course of the day in any decisive way.

Colonel Alvensleben took two more measures: first he sent a single company of guardsmen under Captain Nayhaus to the heights in the south to fight the French guns positioned there at Le Pré-Saint-Gervais . These well-trained shooters showed that it was also possible to fight artillery successfully from a distance. They first decimated the crew and then took the 10 guns. The Prussians, however, were helpless against the artillery fire from the north because they could not cross the Canal de l'Ourcq.

Colonel Alvensleben's second measure was that he repeatedly asked his commanding Marshal Barclay de Tolly for cavalry support - but each time in vain. Barclay de Tolly, who was in Russian service, knew his tsar well and was careful not to send the beautiful horses of the Russian guard cavalry into battle.

As of 12:00 p.m., the bulk of the Silesian Army gradually arrived in front of Paris. This came from the east and still needed hours to reach the specified areas of operation. Larger contingents did not enter the fight until 2 p.m. During this time they were already being fired at by the French troops with artillery. The coalition troops, however, brought their own artillery to use. The French, however, was far more accurate and effective. Quite a few guns of the coalition troops were lost to artillery hits. Here, too, the experience was made that snipers were the most efficient weapon against artillery.

Marshal Blucher was indisposed that day. A severe eye infection forced him to protect himself from the daylight. He spent the afternoon in a closed yellow carriage on a hill near Aubervilliers . Without his own obvious impression of the course of the battle, he could hardly influence it.

Around 1 p.m., the mass of the arriving troops could also be seen from Montmartre. Joseph Bonaparte issued two powers of attorney to Marshals Marmont and Mortier, which legitimized them to negotiate armistice. He immediately left Paris and followed the Empress.

The afternoon from 2:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m.

At 2:30 p.m., the corps of Crown Prince Wilhelm von Württemberg arrived in the south in front of the Bois de Vincennes. It formed two contingents: the Württembergians occupied the park and the Austrians advanced south of it along the Marne and Seine. The following Gyulay corps did not arrive until 4:30 p.m. and hardly took part in the fighting.

At 3:00 p.m. Marshal Barclay de Tolly ordered the Russian troops to advance on the heights in front of Belleville. At the same time, Prussian troops were to attack La Villette and the guns that were successfully operating there. However, the Marshal had no maps of the area and it was unknown to his officers whether the attack was to be made north or south of the Canal de l'Ourcq. So the troops were sent back and forth across the bridge at Pantin until an attack on the north side broke out. This was answered by a failure of the French troops from La Villette. In the following battle it was the Prussian body hussars (Lieutenant Colonel Stoeßel) who took the battery at La Villette and thus enabled the Prussian Guard to advance further towards the Barriere de Pantin.

At 3:30 p.m. Marshal Marmont asked Mortier for support that Mortier could not give. For his part, Mortier asked Schwarzenberg through a messenger for a 24-hour armistice, which the latter refused and in return demanded the surrender of the French troops. Mortier rejected this at the time, but an understanding was reached to negotiate in a house in front of the Barriere de Saint-Denis . There the two Marshals of France and representatives of the coalition troops met, among which Prussia was not represented. They agreed on an armistice from 5:00 p.m., but negotiations continued on the surrender of the French troops until 2:00 a.m. on the morning of March 31, 1814. Then the Marshals of France signed the surrender, which at least allowed them, with theirs To withdraw troops from Paris.

The armistice agreed for 5 p.m. only slowly became known among the widely dispersed troops. Since no representative from Prussia was involved in the negotiations, Marshal Blücher initially did not feel bound by them and allowed Russian troops under his command to storm and occupy Montmartre until 6:00 p.m.

Where was Napoleon?

Napoleon learned on March 27, 1814 in Saint-Dizier of the retreat of Marshals Marmont and Mortier on Paris. A few hours later he decided to move to Paris with his troops, albeit not by direct route, but via Troyes to Fontainebleau . On March 28, he received new news that worried him. On the morning of March 29th, he separated from his troops and arrived in Troyes in the evening, accompanied only by two squadrons of the guard cavalry. On March 30th at 10:00 he rode on, but had to change to a carriage during the day from exhaustion, reached Fontainebleau and continued on the road to Paris. It was already night when his Spanish dragoons and General Belliard , who had been his adjutant in 1813 , met him. From them he learned the outcome of the battle and the armistice. He decided not to go on and returned to Fontainebleau.

The days after

At 11:00 a.m. on March 31, the monarchs of Russia and Prussia entered Paris and held a parade of the guards. All other troops were not allowed to enter Paris. It became known that Napoleon was collecting the remaining troops south of Paris between Melun on the Seine and La Ferté-Alais on the Essonne . Against them, the bulk of the coalition troops south of the Seine were reorganized. For this they had to march around the city. Field Marshal Blucher was still ill. He was replaced on April 2, 1814 by Barclay de Tolly as Commander in Chief of the Silesian Army . On April 3, 1814, the Bülow Corps occupied Versailles .

On April 4, 1814, Napoleon assembled his marshals at Fontainebleau. He wanted to lead them to attack Paris one of the next few days. The marshals refused. Marshal Ney emerged as a spokesman and described the changed political and military situation to Napoleon. He also dared to suggest that Napoleon abdicate as the only way out of the current situation. Napoleon was impressed. On the same day he wrote down his abdication in favor of his son , who was born in 1811 . The Empress Marie-Louise was to become regent. With this deed of abdication, Napoleon sent Marshals Ney and MacDonald and General Caulaincourt as negotiators to the coalition headquarters. Tsar Alexander refused this abdication in favor of Napoleon's son, and Napoleon was asked to abdicate unconditionally.

On April 5, 1814, the Marmont Corps left the French army with 10,000 men. Schwarzenberg did not succeed in integrating this corps into the coalition troops, as agreed in writing the day before with Marmont, because considerable unrest broke out among the troops, but it was able to continue north from Paris.

On April 6, 1814, Napoleon sent his negotiators back to the coalition headquarters with the declaration that he was ready for an unconditional abdication. The following negotiations lasted until April 11, 1814. On that day, the Treaty of Fontainebleau was signed in Paris by all the negotiators involved . On that day at the latest, Napoleon signed his unconditional abdication in Fontainebleau.

On the night of April 12, 1814, to April 13, 1814, Napoleon attempted suicide with poison, which he supposedly always had with him since the fire in Moscow . The poison was almost ineffective.

On April 13, 1814, Napoleon ratified the Treaty of Fontainebleau. On April 20, 1814, he left for Elba.

literature

- Friedrich Christoph Förster, History of the Wars of Liberation 1813, 1814, 1815 , Volume 2, G. Hempel, Berlin, 1858

- Ludwig Häusser, German history from the death of Frederick the Great to the founding of the German Confederation , Weidmann, Berlin, 1863

- JE Woerl, History of the Wars from 1792 to 1815 , Herder'sche Verlagshandlung, 1852

- Karl von Damitz, History of the campaign from 1814 in eastern and northern France to the capture of Paris , ES Mittler, 1843

- Friedrich Saalfeld, General History of the Latest Times - Since the Beginning of the French Revolution , Brockhaus, 1819

- Heinrich Beitzke, History of the German Wars of Freedom in 1813 and 1814 , Volume 3, 1814, Duncker & Humblot, 1855

- Hermann Müller-Bohn: The German Wars of Liberation 1806–1815 , Volume 2, Berlin 1913

- Karl Gottlieb Bretschneider, The Four Years War of the Allies with Napoleon Bonaparte in Russia, Germany, Italy and France in the years 1812 to 1815 , 1816

- Abel Hugo , France militaire, Histoire des armées françaises de terre et de mer de 1792 à 1833 , 1838

- Frank Bauer, Paris March 30, 1814, Small Series History of the Wars of Liberation 1813-1815, H. 39, Altenburg 2014

Individual evidence and supplements

- ↑ Föster, p. 931. Müller-Bohn, p. 798.

- ↑ The exact text can be found in Hugo, p. 255

- ↑ The wording is: Les puissances alliées ayant proclamé que l'empereur Napoléon était le seul obstacle au rétablissement de la paix en Europe, l'empereur Napoléon, fidèle à son serment, déclare qu'il renonce, pour lui et ses héritiers, aux trônes de France et d'Italie, et qu'il n'est aucun sacrifice personnel, même celui de la vie, qu'il ne soit prêt à faire à l'intérêt de la France. - Since the Allies have declared that Emperor Napoleon is the only obstacle to peace in Europe, Emperor Napoleon, true to his oath, declares for himself and his heirs to renounce the thrones of France and Italy and that he is ready to make any sacrifice , even of his life, for the interests of France.