Battle near Gersdorf

| date | May 5, 1813 |

|---|---|

| place | Gersdorf in the Kingdom of Saxony |

| output | Tie with a slight advantage for the allies |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 20,000 | 12,100 |

| losses | |

|

600 dead |

587 dead and 400 wounded |

Spring campaign 1813

Lüneburg - Möckern - Halle - Großgörschen - Gersdorf - Bautzen - Reichenbach - Nettelnburg - Haynau - Luckau

Autumn campaign 1813

Großbeeren - Katzbach - Dresden - Hagelberg - Kulm - Dennewitz - Göhrde - Altenburg - Wittenberg - Wartenburg - Liebertwolkwitz - Leipzig - Torgau - Hanau - Hochheim - Danzig

Winter campaign 1814

Épinal - Colombey - Brienne - La Rothière - Champaubert - Montmirail - Château-Thierry - Vauchamps - Mormant - Montereau - Bar-sur-Aube - Soissons - Craonne - Laon - Reims - Arcis-sur-Aube - Fère-Champenoise - Saint -Dizier - Claye - Villeparisis - Paris

Summer campaign of 1815

Quatre-Bras - Ligny - Waterloo - Wavre - Paris

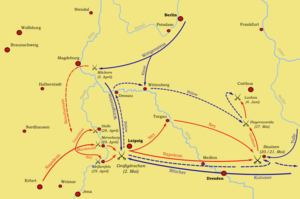

After the defeat of the Prussians and Russians against the Napoleonic troops at the Battle of Großgörschen on May 2, 1813, the allies withdrew towards Meißen and Dresden . On May 5, 1813, there was a battle near Gersdorf (a district of Hartha , also known as the battle near Colditz ). This battle belongs to the Wars of Liberation in Central Europe (also known as coalition wars ) of the Sixth Coalition War .

prehistory

After the battle of Großgörschen on May 2, 1813, the Allied troops were in retreat and moved towards the Elbe . The combined corps of General York and General Blücher were given the route via Colditz, Leisnig , Döbeln, and General Miloradowitsch via Rochlitz , Waldheim , and Nossen .

In order to cover their march from Colditz to Leisnig, the first brigade under Lieutenant Colonel von Steinmetz (von Steinmetz led the first brigade on behalf of the wounded General Hunerbein ) was left behind in Colditz. Von Steinmetz was therefore given the task of holding the French in Colditz until the corps had marched across the bridge in Leisnig and General Miloradowitsch had passed the Mulde in Rochlitz. The defense of the bridge at Colditz, which had previously been set on fire, was entrusted to Major Rudolphi with a battalion of infantry , a detachment of volunteer fighters and two cannons .

The troops of Viceroy Eugène de Beauharnais with the 36th French Infantry Division under General Henri François Marie Charpentier (1769-1831) and the 35th French Infantry Division under General Gerard of the 11th Corps under Marshal MacDonald advanced from Borna to Colditz. Their goal was to put the allied troops on the retreat.

Course of the battle

The French troops advancing rapidly from Borna reached Colditz on May 5, 1813 at 9:00 a.m. and tried to cross the Mulde. As the bridge was set on fire and the Prussian troops were defending the bank, heavy artillery fire began immediately on both sides . The Prussians defended their position so stubbornly that the viceroy had to refrain from using force to make the transition. Instead, he sent a cavalry patrol downstream to look for a ford . Soon the news came back that Sermuth had one.

Thereupon Eugène circumvented with the Charpentier division north of Colditz and crossed the hollow at the ford in Sermuth. The French quickly pushed through Collmen to Commichau, positioned 20 cannons and pushed on towards Leisniger Strasse. This quickly executed flank march brought the Prussians still on the march to Leisnig, but especially the Steinmetz brigade, in distress. If it had been possible to get between the withdrawing bulk and Steinmetz's brigade, the brigade would have been dealt with. She would have either been abraded or captured. Another danger was that the French could have prevented the retreat from Miloradowitsch to Waldheim on reaching the Harthaer Kreuz and even cut him off from the rest of the army.

In order to avoid the impending encirclement, the Steinmetz brigade retreated to the Colditzer Strasse in the direction of the Harthaer Kreuz under heavy combat and grape fire in the flank. General Miloradowitsch, who was coming from Rochlitzer Strasse, noticed the predicament the brigade was in. Immediately he sent a detachment under Lieutenant General Graf St. Priest with the 2nd Grenadier Division, the Life Guard Uhlan Regiment and two companies of artillery to help the Prussians.

Since the Prussians had evacuated Colditz, the French were free to clear the bridge and have it repaired by sappers . From 11:00 a.m., Gerard's 35th Division and General Fressinet's 31st Division, which had meanwhile also arrived in Colditz, were able to cross the Mulde and remained close on the Prussians' heels. Around lunchtime, around 5,000 Prussians and around 4,500 Russians reached Colditzer Strasse near Gersdorf and united to build a defensive position here.

The French divisions Fressinet with 4,500 men and Gerard with 6,500 men reached a wooded area west of Gersdorf and stopped. An immediate attack was not considered, as they were still waiting for the arrival of the 36th Charpentier Division with 7,500 men. Until 2 p.m. the French troops developed as follows:

In the village of Langenau , the Fressinet division formed the right wing. The Gerard division formed the center behind Schönerstädt on Colditzer Strasse, and the Charpentier division, advancing to the left from Commischau's flank march, formed the left wing. In the reserve behind the forest stood the 1st Cavalry Corps under General Latour-Maubourg with 1,500 riders.

The allies moved to the left wing and in the center the 2nd Russian Grenadier Division from St. Priest with 3,400 men. The focus was on the 1st Russian Battery and the Russian Body Guard Uhlan Regiment. Behind Obergersdorf, the von Steinmetz brigade with 4,500 men and the 2nd Leib Hussar Regiment under Major von Kall with 300 men formed the right wing. A Russian fighter regiment with 500 men and the Litthau Dragoon Regiment with 200 men were set up in Gersdorf as the advanced right wing . A Russian Uhlan regiment, two Russian fighter regiments with 1,500 men, two Cossack regiments with 1,000 men under General Lisanyevich and a Russian battery with 100 men under Colonel Sipjagin stood in reserve in Hartha.

After Eugène had reunited his two divisions, he gave MacDonald the order to attack at 2:30 p.m. It began with a violent cannonade of 40 guns on the Prussian-Russian positions. The allies then returned fire from 20 tubes. After the cannonade, which lasted about 30 minutes, 10 French battalions advanced in a loose formation on the Prussian-Russian infantry lines. After effective rifle fire on both sides, the bayonet was defended by the allies. During the resulting brief retreat of the Gerard and Freissignet divisions, Prussian hussars and Russian lancers advanced successfully. This in turn resulted in a large French counterattack with 1,000 horses on the opposing positions of the allies. The Latour-Maubourg cavalry corps drove the Prussian body hussars and Russian Uhlans back to their original positions. The line infantry and artillery then withdrew to the heights of the Harthaer Kreuz.

At the same time several battalions of the Charpentier division advanced on Gersdorf. The French, experienced in house-to-house warfare, conquered Gersdorf and drove out the Prussians there. The latter withdrew first to the upper village and then to the Harthaer Kreuz, with great losses. The Simmer Brigade from the Charpentier Division reached Leisniger Strasse at 4:30 p.m. From the road as well as from the ridge, Steinmetz's brigade was cut off the route of retreat to Döbeln. A retreat was therefore only possible with the Russians via Waldheim.

The battle almost turned into a defeat when General Miloradowitsch himself arrived on the battlefield with new troops. The Jägerbrigade under General Karpenko with the 1st, 33rd and 37th Jägerregiment threw the French back again. The rest of the infantry of Miloradowitsch's corps also gained great advantages over the French, who were delayed for some time. But they could not withstand the increasing pressure of the French for long. The hastily advanced French cavalry and artillery cannoned the Steinmetz brigade and the 2nd Russian infantry division and their hunter units, which were moving towards Waldheim. At 6:30 p.m. the Viceroy broke off the fight because his troops could no longer advance due to the falling darkness.

Evaluation of the battle

The battle had no winner, but the allies had a slight advantage, because the tough resistance and their repeated attacks with fresh troops prevented the French from achieving what they were aiming for the day. Neither did they succeed in cutting off Steinmetz's brigade and withdrawing it from the enemy's army by destruction or capture, or in preventing the last part of the Russian army from passing through the Zschopau in Waldheim. The French had to bivouac in Gersdorf and on the Harthaer Kreuz and Eugène moved into the Gersdorf parish.

Since the battle was very persistent, there were many dead and wounded on both sides. According to Prussian information, 250 Prussians and 337 Russians are said to have fallen. Around 400 wounded were carried from the battlefield, many of whom died in Waldheim in the following days. According to Prussian information, the French are said to have lost 700 to 800 men. Reliable Russian information is missing.

In the viceroy's report, Napoleon swindled that he had lost 100 dead, 600 to 700 wounded, but the enemy had lost 500 to 600 dead, 1,500 wounded and 100 prisoners. Emperor Napoleon was by no means satisfied with the success and wrote back from Colditz:

“L'Empereur au Vice-Roi

Colditz, 6 May 1813, 3 heures et demie du matin

Mon fils, la journée d'hier aurait été belle, si vous m'aviez envoyé 3000 prisonniers. Comment dans des gorges et dans un pays où la cavalerie de l'ennemi est inutile, ne m'envoyez-vous personne?The Kaiser to Viceroy

Colditz, May 6th, 1813, half past

three in the morning My son, yesterday would have been nice if you had sent me 3,000 prisoners. How does it come about that in the deep valleys and a country where the enemy cavalry cannot be used, you send no one to me? "

All wounded (French, Prussians and Russians) were initially cared for in Gersdorf and transferred to Hartha, Waldheim and Colditz the next day. The more than 1,000 fallen were buried in mass graves in and around Gersdorf.

On May 6th, Napoleon, coming from Colditz, inspected the battlefield. Then he rode on via Flemmingen and Hartha to Waldheim. The Russians and the Steinmetz brigade negotiated the sole pursuit of the French as far as Dresden through the battle near Gersdorf, while the main army was able to pass the Elbe unmolested in Meißen. In the following days there were two more individual clashes between Eugène's troops and the rear guards, on May 6, 1813 in Etzdorf and on May 7, 1813 near Wilsdruff .

Wounded persons known by name and victims of the battle

- Georg Friedrich von Kall , Major and Regimental Leader of the 2nd Leib-Hussar Regiment, wounded, died in Hartha and buried in the Waldheim cemetery

- von Zastrow, Major and Regimental Leader of the 9th Infantry Regiment (Kolberger Regiment), wounded

- von Werder, second lieutenant in the 9th Infantry Regiment (Kolberger Regiment), fell.

Memorial stones for the battle

- Memorial stone for the battle : The memorial stone was erected on May 5, 1913 at what is now Bundesstrasse 176 near Gersdorf. It is adorned with a cannonball, two crossed swords and the date May 5, 1813.

- Napoleon stone : The Napoleon stone is in Waldheim on Kriebsteiner Straße on the banks of the Zschopau. On May 6, 1813, Napoleon sat on this stone and watched his troops pass through Zschopau. The inscription was added after 1870.

- Grave of Georg Friedrich von Kall : Major von Kall, commander of the 2nd Leib-Hussar Regiment, was hit by a cannonball on the battlefield of Gersdorf on May 5, 1813 and died in Hartha. He was buried in the Waldheim cemetery. In 1913 his grave was restored and given a stone slab.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hans von Krosigk, Field Marshal von Steinmetz , shown from the family papers, Berlin 1900, page 5

- ↑ Hans von Krosigk, Field Marshal von Steinmetz , shown from the family papers, Berlin 1900, page 9

- ↑ Hans von Krosigk, Field Marshal von Steinmetz , shown from the family papers, Berlin 1900, page 10

- ↑ a b Overview of the campaign of the Kaiserl. Royal French and KK allied Russian-Prussian armies in 1813 , vol. 1, Weimar 1813, page 20

- ↑ Overview of the campaign of the Imperial French and Imperial Russian-Prussian armies in 1813 , vol. 1, Weimar 1813, page 21

- ^ Döbelner Heimatschatz, collection of local history essays by the “Döbelner Erzählers”, 2nd volume, Döbeln 1923, page 206

- ^ Arthur von Horn, History of the Royal Prussian Leib-Infanterie-Regiment , Berlin 1860, page 528

- ↑ Döbelner Heimatschatz, collection of local history essays by the “Döbelner Erzählers”, 2nd volume, Döbeln 1923, page 202

- ^ Carl von Plotho, The War in Germany and France in the Years 1813 and 1814 , Vol. 1, Berlin 1817, page 129

- ^ Johann Sporschil, The German Wars of Freedom in the Years 1813, 1814, 1815 , Vol. 1, Braunschweig 1845, page 165

- ^ Carl von Plotho, The War in Germany and France in the Years 1813 and 1814 , Vol. 1, Berlin 1817, page 130

- ^ Emil Reinhold, Geschichtliches Heimatbuch des District Döbeln , Döbeln 1925, page 166

- ^ A b Emil Reinhold: Geschichtliches Heimatbuch des Bezirk Döbeln , Döbeln 1925, page 167

- ↑ Döbelner Heimatschatz, collection of local history essays by the “Döbelner Erzählers”, 2nd volume, Döbeln 1923, page 207

- ↑ a b Heinrich Beizke: History of the German wars of liberation in the years 1813 and 1814 , Vol 1, Berlin 1859, page 319th

- ↑ a b von Bagensky, History of the 9th Infantry Regiment known as Colbergsches , Kolberg 1842, page 275