Teaching principles

Teaching principles (also: didactic principles or pedagogical principles ) are general principles for the design of education and teaching . As rules they claim to be valid for all organized teaching and learning according to the state of knowledge of the time. A distinction must be made between largely recognized formal and sometimes controversial, content-oriented principles.

Concept and meaning

As the term "teaching principles " already expresses, these are principles of teaching and learning that are important for all teaching, regardless of a subject structure of the educational content or interdisciplinary education. They are part of the basic knowledge of scientifically trained teachers at all school levels and accordingly play a central role in the practical and theoretical training of trainee teachers and their corresponding qualifications.

In didactic literature, the terms “pedagogical principles” or “didactic principles” are often used by the same authors , synonymous with the technical term “teaching principles” .

The traditional "theoretical subjects" mathematics or German lessons have not been mere "sitting subjects" for decades, while the subjects of technology or physical education, which are known to be action-intensive, have long since ceased to be pure "exercise subjects".

A contemporary modern teaching combines theory and practice, action and reflection, individualization and socialization, activity and leisure ( " school " means Greek originally " leisure "), play and seriousness, Schonraum learning and real space learning , teaching objectives and student interest in the form of a multidimensional teaching and learning with each other . In this respect, many of the older principles of a still polarizing didactic discussion today do not have a contrasting, but complementary meaning. Modern teaching avoids ideological biases and flexibly adapts the generally applicable principles to the respective objectives. This means that teaching principles are not related to specific subjects, that their application rather depends on curricular requirements, changing teaching goals, different methodological priorities, special educational intentions, on the chosen topic and on the level of maturity and level of development of the learners and must be handled flexibly. It means that the principles do not all apply at the same time, but are determined by the type of teaching used (teacher-centered or project-oriented, technical or interdisciplinary work, etc.). This requires well-trained didactic teachers who have an overview of the spectrum of didactic possibilities and who have learned to use them professionally.

Historical

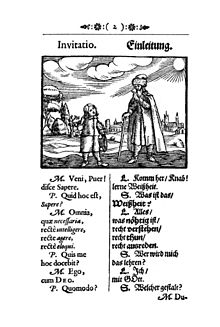

Johann Amos Comenius (1592–1670) is considered the father of modern didactics . In his famous pedagogical standard work, Didactica magna or Große Didaktik , written between 1627 and 1638 and published for the first time in 1657, Comenius already formulated principles for teaching adolescents, which for the most part have endured into today's teaching:

- Learning should primarily take place through one's own actions.

- Teaching occurs through sensual and natural illustration.

- The teacher should not convey things in nature abstractly, but show the thing itself.

- The visualization is to be given priority over the linguistic communication.

- The living example and role model must take precedence over words and regulations.

- Newly learned things are to be consolidated through practice.

- It is necessary to dwell on the object until it is fully understood.

- The teacher shows the way "in which everything can be achieved easily and safely."

- Comparative examples should be used to verify theses.

- It is important to develop a curriculum and proceed from easy to difficult, from general to specific.

- The mother tongue has priority over a foreign language .

According to Comenius, philanthropists such as Basedow , Salzmann and GutsMuths, as well as educators such as Pestalozzi, focused on working out a child-friendly learning system and corresponding rules in the 18th century .

In the 20th century, reform pedagogy dealt with the topic again. The doctor and pedagogue Maria Montessori made the child's personality the starting point and focus of the lessons with her teaching principle “from the child”.

Consensus-based didactic principles

The sports scientist Annemarie Seybold -Brunnhuber collected the most important principles of pedagogy, which was reoriented after the Second World War , in several high-circulation publications between the 1950s and 1970s and worked them up for her subject, which was then still called "physical education". Since then, they have been taken up and modified again and again.

In a new synopsis, the didactic engineer Siegbert A. Warwitz describes eleven "didactic principles" which he sees as generally recognized in today's didactics and on which modern teaching should be based. These are formal requirements related to the design of the lesson, which provide a framework for teaching and learning based on the scientific knowledge of today's teaching. Controversial content-related or ideological biases are excluded:

Principle of age and development equality

Teaching children, adolescents or adults requires different didactic measures. The teacher must adapt to the respective addressees in terms of language and speed, facial expressions and gestures, methodology and lesson organization. Teaching in preschool and elementary school requires a higher degree of sensible perception, and with the progress made in learning and development in high school and university, it also allows abstract, science- related teaching and learning, for example in lectures , seminars and internships .

The principle of age and development equality postulates that the learners have to be picked up at their respective level of competence and interest in order to enable effective learning.

Principle of wholeness

Higher education with scientific demands follows the "principle of science orientation" and the "principle of multiple perspectives" . This resulted in a breakdown of reality into specializing subjects and disciplines and a loss of wholeness, which only reassembled in the overall view of the subjects. However, only very few learners are able to achieve this. In addition, natural learning outside of school does not take place in artificially formed categories and disciplines. The principle of wholeness is intended to counteract this fragmentation of the worldview.

Wholeness or wholeness means, in contrast to the coincidental coexistence or the additive accumulation of learning content, a primeval closedness from which the meaning of the integrated areas is derived and which is characterized by an indissoluble causal relationship ("the whole is always more than the sum of its parts") .

The principle of wholeness also refers to the person of the learner, who not only learns with his or her intellect and should be perceived as a person with diverse talents and interests. Pestalozzi already called for the participation of “head, heart and hand” in his idea of elementary education , that is, non-isolated activities in the cognitive, emotional and practical areas. In the form of multi-dimensional learning , the whole principle has found a contemporary design.

Principle of clarity

The principle of clarity makes it clear that learning should take place less on an abstract than on a pictorial level. The learning object should be sensually tangible for the learner. From the point of view of the teacher's task, the “principle of illustration” is also used.

Illustration means presenting the subject matter in such a way that the pupils can absorb it with the help of their sense organs and according to their comprehension. An intuition is present when the details of what has been recognized can be coherently assigned to previous experiences as a whole. Young children in particular depend on illustration, as it increases learning effectiveness and memory retention.

In reform pedagogy , the principle was propagated from many sides: Rousseau spoke of "experience in things", while Pestalozzi called for "view as an educational force".

Principle of role model effect

In his Didactica magna, Comenius already gave the role model effect of the teacher an outstanding rank in education, recognizing that the living example triggers more than many words and regulations. Conversely, a bad role model counteracts the educator's well-meaning parenting advice and makes it untrustworthy in the eyes of the pupil. Since the credibility of the teacher is of great importance for the success of an education, words and deeds, required and personal behavior of the teacher, must be brought into agreement.

Principle of structuring and progression

Professional teaching is not playful and does not indulge in mere employment, but works towards a specific goal. The didactics therefore also speak of the "principle of goal orientation" . A well-planned lesson has a so-called "lesson structure", which methodically and organizationally structures the teaching of the material and the learning behavior. It consists of an introductory, a main and a final part. More extensive teaching units require a content structure and a process structure based on a previous "learning structure analysis".

The demanding, interdisciplinary project teaching follows a six-stage “phase structure” from the exploratory phase, the motivation phase, the planning phase, the preparation phase, the implementation phase and the reconsideration phase.

The principle of structuring and progression primarily relates to the selection of the content and the design of the method . It is also known under the terms “principle of small steps” , “from simple to complex” and “from easy to difficult” .

Principle of repetition and variation

The first structure formation in the learning process does not guarantee lasting success. The learning success should, however, be maintained over a longer period of time and the knowledge and skills acquired should be secured against forgetting and decay. Methodical measures such as repeating, varying, practicing, training and applying what has been learned in practice and the transfer to other areas are used for this. This criterion of good teaching can sometimes also be found under the term “principle of consolidation” .

Principle of self-activity

The teaching principle of self-activity , which can also be found in the literature under the name of self-organization or (seen by the teacher) as the "principle of motivation" or "principle of activation" , aims at the learner's own activity in accordance with the guiding principle of Montessori education "Help me, to do it yourself ”. Activation or motivation means stimulating the pupil and giving him the opportunity to gain learning experiences while actively dealing with things. The principle of activation attempts to induce self-activity in the student (on his own initiative with freely chosen means and social reference to a goal). It is required here that the teacher or educator does not terminate obvious failed attempts prematurely, but rather gives the student the opportunity to learn from their own actions. This principle already gained importance when the project work was designed by John Dewey (“ Learning by Doing ”) and Georg Kerschensteiner (“The origin of all thinking lies in practical doing”). It is the task of the teacher to arouse the interest in the subject and the learning and performance needs of the students. The student has the task of maturing from a passive recipient to an active designer of their own learning processes.

Principle of security

This principle takes into account the need for protection of adolescents: School should enable space learning that allows experimentation, trial and error without allowing serious harm. It means allowing risk as an essential element of a dynamic learning process, even promoting it, but creating a safe framework that protects against serious mistakes and excessive demands. It is not only about protecting against physical dangers, as can arise in action-intensive subjects such as physical education or technical subjects such as chemistry, physics and technology lessons, but also about mental health in communicative interaction in the learning community. The goal is the gradual assumption of self-assurance and the release into the ability to live, which is demanded by the outside world.

Principle of systematics and consistency

Professional teaching is not a haphazard act. Rather, it is systematically geared towards achieving a teaching goal (goal- oriented principle) . This manifests itself in a well thought-out but flexible structure of the lessons that takes into account the real course of the learning process and, if necessary, modifies the pre-planned processes (problem-oriented principle) .

The goal orientation, on the other hand, must not come to nothing, but must consequently undergo a final check of what has been achieved. In didactics, this indispensable measure is also referred to as the “principle of securing success” : An effective safeguarding of success takes stock of the learning success as objectively as possible , which must be measured against the objectives. The target and actual state must be brought into the best possible approximation. Only when it is ensured that the initial targets have actually been achieved can the further didactic procedure be planned sensibly.

The system and consistency of teaching require feedback on learning progress for both teachers and students. It manifests itself in the "principle of confirmation of success" . Confirmation of success is an important part of teaching and learning. The findings of learning psychology show that learning success is largely determined by the emotional, but especially the factually differentiated feedback. The learner is given feedback on the success or failure of his or her learning processes in order to initiate further learning successes. According to the teaching, these should be as substantiated, concrete and relevant as possible and not be limited to superlatives and general terms such as (“great”, “top”, “WOW” etc.) of the teacher. The main function of the confirmation of success is to provide information about the current learning status, to determine the further learning process and to maintain or improve the willingness to learn. The objective information is primarily used for this purpose. But also the subjective influencing measures such as the fair distribution of praise and criticism determine the working atmosphere and the will to learn.

Principle of actuality

School lessons are deliberately carried out largely as safe space learning and thus complies with the “principle of safety” . In doing so, however, he should not disconnect himself from the realities outside of school and should include events and experiences of social reality again and again in the classroom. This happens, for example, in so-called real space learning on excursions and when visiting extracurricular learning locations . In addition to historical knowledge, daily events must take up space in the learning processes. Student and school problems may not authoritarian overly regulated, but must be made the subject of lively discussion of instructional and processing.

Principle of individuation and socialization

This teaching principle takes into account the two fundamental ways of experiencing the adolescent as individual and social beings, both of which want to be lived out and trained. As a unique individuality , the child brings their own skills and interests with them. In socialization, on the other hand, it learns to find its position in a social network and to integrate into its social environment and society.

In terms of the teacher's task description, the term “principle of student orientation” or “principle of child orientation” is sometimes used . It wants to emphasize the individuality and recognition of the personality of the student in all areas of the lesson. This applies to the form of interaction, mutual respect for dignity and an open and trusting partnership. Sabine Ragaller distinguishes three aspects of "child orientation" for primary schools :

- Take seriously the essential characteristics of the elementary school child, his childhood

- Recognize the individuality (biography, interests, needs) of each child

- Take into account the current life situation of the children (changed childhood, life and interests of today's children).

The methodically understood principle of differentiation is closely related to student orientation . It focuses on the individuality of each child and their special needs. Differentiation means the dissolution of the heterogeneous class association in favor of homogeneous groups with regard to the performance or interests of the students. In extreme cases, differentiation goes as far as "fitting" or "individualization". It is hoped that this will enable the individual student to be better picked up at their respective level of development.

The differentiation has a long school history. Schools of ancient Greece already offered different areas to which one could turn according to one's own abilities. In the Middle Ages , regardless of age, one moved into certain departments after testing one's knowledge. While Comenius advocated the formation of year classes , Maria Montessori, among others, advocated individualizing processes with the aim of “self- education” in reform pedagogy .

A distinction can be made between the internal differentiation or the internal differentiation (within the class group differentiation in terms of degree of difficulty, type of learning offer, additional offers) and the external differentiation , which describes the differentiation within the school by type of school or within the school the respective school structure.

Partly applicable didactic principles

Controversial and therefore only partially or regionally valid are “principles” that set out certain guidelines and (one-sided) propagate political, religious, ideological orientations. Thus, under dictatorial regimes , in democratic societies, in an Islamic madrasah , in a Christian school, in a general school , in a specially oriented private school , in a regular school or in an alternative school , different (above all with different content) principles that are ideological or educational apply want to have a certain influence on the learner's mindset.

But different “educational principles” can also be identified historically: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe saw the teacher as a “discipline master” and, in accordance with his autobiography, assumed the ancient Greek motto Ὁ μὴ δαρεὶς ἄνθρωπος οὐ παιδεύεται ( Ho mä dareis anthropos ‚The paideuetai not abused man is not brought up ' ). But even with Plato and the wisdom teachers of the various ancient cultures there was also a partnership-based learning community without coercion and drill on the basis of an application and a call to become a student.

International discussion

In the USA, Robert Gagné's “Nine Events of Instruction” are among the best-known approaches to lesson planning.

Critical reception

The criticism of the various teaching principles represented reaches a wide range. It often presents itself as contradicting and contradicting itself. Some denounce terminological imprecision, others an ideological overload. From a scientific point of view, they are occasionally criticized as being too practice- related and suspected of overly regulating or standardizing teaching. Sometimes the critical accusations attain a polemical character: They are used as a pointer to deficiencies, e.g. For example, the principle of activation as a critique of the “cerebral” (too much dominated by the intellect ) lessons or the mutual play-off of “ student-centered lessons ” and “ teacher-centered lessons ”.

Teaching principles have therefore recently been more formally restricted to the structuring and design of lessons. They should not be viewed as regulations , but as guidelines for pedagogical and didactic decisions that merely outline a desirable orientation. Its validity is general and affects all areas of education and school subjects, all ages and types of school.

In the course of the self-discovery of pedagogy, the once polemically formulated emphases in particular have proven to be one-sided. With their partial authorization, they are now integrated into the overall picture as complementary aspects of multi-dimensional teaching and learning and a methodologically and organisationally varied teaching method geared towards the different learning goals and learning skills. One-sided teaching concepts, as far as they are still practiced - for example in private institutions - no longer correspond to the state of research of the time and general teaching practice. They present themselves as "outsider education".

Criticism of the formal character of the principles (mostly expressed by those interested in content and ideology) is wrong insofar as the principles aim to provide precisely this - ideology-free - framework for good teaching. They are intended to enable a general consensus on a didactic and scientific basis and not on the basis of a specific ideology. Criticism is widely considered to be justified when ideologically one-sided standards are given as “principles” and certain religious, political or ethical preferences are to be fixed. Controversial ideas about “teacher dominance” or “student dominance”, “ inclusion or special needs school ”, “ coeducation ” or “ gender-specific education ” are suitable for argument-based, factual discussion, but not for setting didactic principles.

literature

- HJ Apel, W. Sacher (ed.): Study book school pedagogy. Bad Heilbrunn 2005, ISBN 3-7815-1364-5 .

- Johann Amos Comenius: Great Didactics: The complete art of teaching everyone everything. 10th edition. Edited by Andreas Flitner. Klett-Cotta, 2008 (original 1657).

- Hans Glöckel : About the class. Textbook of general didactics. 4th edition. Bad Heilbrunn / Obb. 2003, ISBN 978-3-7815-1254-2 .

- G. Gonschorek, S. Schneider: Introduction to school pedagogy and lesson planning. Donauwörth 2005, ISBN 3-403-03216-7 .

- Andreas Gruschka : How students become educators. Study on competence development and professional identity formation in a dual qualification course of the collegiate school experiment NW. Wetzlar 1985

- Herbert Gudjons: hands-on didactics. Bad Heilbrunn 2003, ISBN 3-7815-1269-X .

- W. Jank, Hilbert Meyer: Didactic models. Frankfurt 2002, ISBN 3-589-21566-6 .

- H. Kiper, H. Meyer, W. Topsch: Introduction to school pedagogy. Cornelsen, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-589-21657-3 .

- Edmund Kösel: Didactic principles and postulates. In: The modeling of learning worlds. Volume I: The theory of subjective didactics. 4th edition. Balingen 2002, ISBN 3-8311-3224-0

- H. Schröder: learning - teaching - teaching. Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-25973-3 .

- Annemarie Seybold: Pedagogical principles of physical education (= contributions to teaching and research in physical education. Issue 1). Ed. Committee of German physical educators. 1954 (awarded the Carl Diem Prize).

- Annemarie Seybold-Brunnhuber: The principles of modern pedagogy in physical education (= contributions to teaching and research in physical education. Volume 1). Hofmann, Schorndorf 1959.

- Annemarie Seybold-Brunnhuber: Didactic principles of physical education (= contributions to teaching and research in physical education. Volume 48). Hofmann, Schorndorf 1972.

- AM Strathmann, KJ Klauer: Learning process diagnostics: An approach to long-term learning progress measurement. In: Journal for Developmental Psychology and Educational Psychology. 42, 2010, pages 111-122.

- Siegbert Warwitz, Anita Rudolf: The objectification of success controls. In: Siegbert Warwitz, Anita Rudolf: Project teaching. Didactic principles and models. Hofmann, Schorndorf 1977, ISBN 3-7780-9161-1 , pages 24-27.

- Siegbert A. Warwitz: Learning objectives and learning controls. In: Siegbert A. Warwitz: Traffic education from the child. Perceive-play-think-act. 6th edition. Schneider, Baltmannsweiler 2009, ISBN 978-3-8340-0563-2 , pages 23 and 26-28.

- Siegbert A. Warwitz: Didactic principles. In: Siegbert A. Warwitz: Traffic education from the child. Perceive-play-think-act. 6th edition. Schneider, Baltmannsweiler 2009, ISBN 978-3-8340-0563-2 , pp. 69-72.

- Werner Wiater: teaching principles. Donauwörth 2001, ISBN 3-403-03617-0 .

- Benedikt Wisniewski: On principles of good teaching. In: B. Wisniewski, A. Vogel: School on astray - myths, errors and superstitions in education. Schneider, Baltmannsweiler 2013, ISBN 978-3-8340-1256-2 .

Web links

- Grünkorn, Diana and Dr. Pfriem, Peter: Teaching principles - definitions, overview, connections

- Heid, Helmut: Quality in Teaching Practice ( Memento from December 25, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF document; 94 kB)

- Wolff, Jürgen: Teaching principles according to Brunnhuber for the preliminary / debriefing and evaluation of lessons

Individual evidence

- ↑ Werner Wiater: Lehrprinzipien , Donauwörth, 2001

- ^ Annemarie Seybold-Brunnhuber: The principles of modern pedagogy in physical education , Volume 1 of the contributions to teaching and research in physical education, Verlag Hofmann, Schorndorf 1959

- ↑ Annemarie Seybold-Brunnhuber: Didactic principles of physical education . Volume 48 of the articles on teaching and research in physical education, Verlag Hofmann, Schorndorf 1972

- ↑ Edmund Kösel: Didactic principles and postulates , in: Die Modellierung von Lernwelten , Vol. I. The theory of subjective didactics , 4th edition, Balingen 2002

- ^ Johannes Kühnel: New building of arithmetic lessons. A handbook of pedagogy for a special field. Klinkhardt, Leipzig 1916. (Eugen Koller (Ed.), 10th edition, Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn / Upper Bavaria 1959)

- ^ Siegbert Warwitz: On the cognitive component in the socialization process . In: ADL (Ed.): Socialization in Sport . Schorndorf (Hofmann) 1974. pp. 366-370

- ↑ Annemarie Seybold: Pedagogical principles of physical education . Ed. Committee of German physical educators. Contributions to teaching and research in physical education. Issue 1, Schorndorf 1954

- ↑ Edmund Kösel: Didactic principles and postulates , in: Die Modellierung von Lernwelten , Vol. I. The theory of subjective didactics , 4th edition. Bahlingen 2002

- ^ Siegbert A. Warwitz: Didactic Principles , In: Ders .: Traffic education from child. Perceiving-Playing-Thinking-Acting , Verlag Schneider, 6th edition, Baltmannsweiler 2009, pp. 69–72

- ^ Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi: How Gertrud teaches her children . Literary tradition. 2006

- ^ Siegbert Warwitz, Anita Rudolf: Projects . Basic item. In: Sports Education. 6 (1982) 16-23, pp. 19/20

- ^ Siegbert A. Warwitz: Learning goals and learning controls , In: Ders .: Traffic education from child. Perceiving-playing-thinking-doing , Baltmannsweiler, Schneider-Verlag, 6th edition 2009. Pages 23 and 26-28

- ^ Siegbert Warwitz, Anita Rudolf: The objectification of success controls . In: Dies .: Project teaching. Didactic principles and models . Verlag Hofmann, Schorndorf 1977, pages 24-27

- ↑ AM Strathmann, KJ Klauer: Learning progress diagnostics: An approach to long-term learning progress measurement . Journal for Developmental Psychology and Educational Psychology 42 (2010) pages 111-122

- ↑ Hans Glöckel: From teaching. Textbook of general didactics . 4th edition, Bad Heilbrunn / Obb. 2003

- ↑ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: From my life. Poetry and truth. Leipzig 1899

- ↑ http://voetterle.de/wp-content/uploads/2008/08/zammlung_u_prinzp.pdf