Venice Carnival

The historical Carnival in Venice ( Carnevale di Venezia in Italian ) is the best known with its masks , animal fights , Hercules games and fireworks, alongside those of Florence and Rome . Starting from the Italian royal courts, increasingly splendid and elaborate forms of carnival have developed since the late Middle Ages . In general, the feast of Epiphany (January 6th) lasted until the beginning of Lent on Ash Wednesday . The origin of the Venetian carnival goes back to the Saturnalia of antiquity and thus customs and festivities from before Lent to the 12th century. The victory of Venice over Aquileia in 1162 was celebrated every year until 1797. In Venice, the carnival was celebrated on St. Stephen's Day (December 26th). Until 1796 it was always followed by a happy feast during Ascension Mass.

history

A carnival festival ( pullus carnisbrivialis ) in Venice is first mentioned in the chronicle of Doge Vitale Falier for 1094. The oldest verifiable mention of a mask in Venice is the description of a guild parade at Martino da Cànal and therefore only dates from the 13th century. During Giacomo Casanova's lifetime in the 18th century, the carnival reached its greatest splendor, at the same time the customs became more and more relaxed.

The heyday of Carnival in Venice ended when, in 1797, the Republic of St. Mark lost its independence through Napoléon Bonaparte and Austria was annexed. The subsequent economic decline severely affected the city's self-image. There were hardly any elaborate processions and pageants. In addition, there are various, sometimes contradicting, references to prohibitions and restrictions of the carnival between 1797 and 1815. For example, a ban on wearing masks is said to have been lifted under the Regno italico . The occasional statement that Napoléon banned the Venetian Carnival, which is why it was no longer celebrated in Venice until 1979, goes too far, because Carnival was also celebrated in Venice during the 19th century. In the course of the Risorgimento and especially after the defeat of Venice in the First Italian War of Independence in 1849, the people of Venice boycotted public events and closed theaters, which also affected the carnival, as a sign of passive resistance.

Carnival was celebrated in Venice in the 19th century, although the economic situation of large parts of the population was very difficult, mainly as a private festival with artistic creations and as an event by Austrian officers, whereby events of the occupying power were temporarily avoided by the locals. After the unification of Venice with Italy on October 18, 1866, efforts were made to revive the great tradition of Venetian festivals.

“In 1867, only a few months after Venice was annexed to the Kingdom of Italy (October 19, 1866), the Venetians celebrated a carnival festival with a rich program for ten days from February 24 to March 5. A 'Società del Carnevale', made up of 'brava gente benemerita', decent and respectable citizens, organized the festivities. Carnival should no longer be a private affair. The declared aim of the organizers was rather to 'attract strangers who bring money' ... as read in the 'Corriere di Venezia' of January 10, 1868 ... The event was financed by a subscription whose first signatory was Amadeo d'Aosta, the son of King Vittorio Emanuele II, and the Mayor of Venice were ... However, the festival was 'a brief fire that burned down quickly', as contemporaries described it. "

A sustained revival of the Venetian Carnival was only triggered by Federico Fellini's film Casanova in 1976. Federico Fellini, the theater director Maurizio Scaparro , the mask maker Guerrino Lovato and numerous other artists organized the revival of the carnival, which was a great success, especially at the 1979 Biennale . Eventually, the hotel owners took on the carnival, which has now become an international tourist attraction. Traditional events were taken up again. For example, the theatrical form of the commedia dell'arte , which is also largely based on the modern carnival masks, has returned to the stage and is performed both in the theater and outdoors.

In 2020, the Venice Carnival ended on February 23, 2020, two days earlier than planned, due to the threat posed by the COVID-19 pandemic .

Carnival bustle

Historical

During the time of the Republic of Venice , the Thursday before Ash Wednesday was not just the actual start of Shrovetide . On this day, the victory of Doge Vitale Michiel II over Ulrich II von Treffen , Patriarch of Aquileia, on the giovedì grasso (ven. Berlingaccio ) of the year 1162 was celebrated. For this reason, the Doge traditionally took part in the celebrations himself, along with the Senate and the ambassadors.

Fireworks were set off in the piazzetta. Groups of young people danced the Arabic moresca , and young fellows from this side and the other side of the Grand Canal built human pyramids. The guilds of blacksmiths and butchers slaughtered the oxen and pigs originally to be delivered every year by the Patriarch of Aquileia as a festival contribution ; however, this bloody tradition became harmless entertainment after 1420.

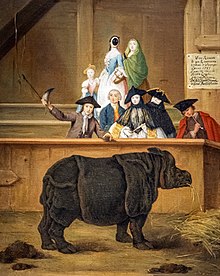

Among the many performances on St. Mark's Square , the puppet theater under the campanile was particularly popular, staging new adventures of traditional masks. In addition, wild and exotic animals were presented in kennels to the amazed audience. Otherwise there were lotteries, teeth were extracted, astrologers prophesied the future, quacks sold medicines. Acrobats and tightrope walkers performed in the corners of the square. The festival reached its climax with the so-called angel flight, first performed in 1548 : an acrobat climbed over a double rope anchored to a raft in the bay in front of St. Mark's Square to the top of the campanile and from there threw flowers into the crowd; then he balanced down to the stands in front of the Doge's Palace .

The carnival season was also the main season of the theaters. The variety of festivities knew hardly any limits during the carnival. The bull chasing was famous, as were the bloody fights between dogs and bears. To the delight of the locals, lavish costume parties took place in the most beautiful buildings in Venice, and the most beautiful masks were presented in the alleys. Shrove Tuesday, the last day of Carnival, the festival finally reached its climax. Thousands of masqueraders ran through the torch-lit streets. Finally, between the two columns on the southern edge of the piazetta in front of St. Mark's Square, an enormous figure wearing a Pantalone mask was burned while the crowd chanted: “It's over, it's over, the carnival is over!” The fasting bell of San Francesco della rang Vigna slowly and entered the Lent.

Modern

Nowadays, the carnival officially opens on a Sunday 10 days before Ash Wednesday. The first festivities often start a week in advance. During the Angel's Flight ( Volo dell 'Angelo ), an artist hovers on a steel cable secured from the Campanile over St. Mark's Square. There are artistic and artistic performances on various stages in the city. Private individuals stroll through the city in costumes, mostly around St. Mark's Square , of course. Most visitors arrive on the weekend before Ash Wednesday; In addition to tourists from further afield, there are also many day tourists from the surrounding area (as far as Austria). For the costumed, the parade and the awarding of prizes for the most beautiful costume on Sunday are the highlight. Here are the winners of the last few years:

- 2006: 1st place: "The Mists of Avalon", Chair: Vivienne Westwood

- 2007: 1st place: "La Montgolfiera" by Tanja Schulz-Hess

- 2008: 1st place: "Luna Park" by Tanja Schulz-Hess

- 2009: 1st place: "Marco Polos Reisen" by Horst Raack and Tanja Schulz-Hess, Chair: Gabriella Pescucci

- 2010: 1st place: "Pantegane" from England

- 2011: 1st place: "Omaggio a Venezia" by Paolo and Cinzia Pagliasso and Anna Rotonai from Rome, shared with "La Famille Fabergé" by Horst Raack, and 1st place in the special category "19th century" to Lea Luongsoredju and Roudi Verbaanderd from Brussels.

- 2012: 1st place: "Teatime" (il servizio da tè del settecento) by Horst Raack, as well as 1st place in the special category "Most original costume" to Jacqueline Spieweg for "Oceano".

- 2013: 1st place: “Alla Ricerca del Tempo Perduto” by Anna Marconi, Senigallia (AN), as well as 1st place in the special category “Most colorful costume” for “Luna Park”.

- 2014: 1st place: "Radice Madre" by Maria Roan di Villavera, shared with "Una giornata in campagna" by Horst Raack

- 2015: 1st place: "Le stelle dell 'amore" by Horst Raack, 1st place in the best costume category on the subject: "La regina della cucina veneziana" by Tanja Schulz-Hess, 1st place in the most original costume category: "Monsieur Sofa et madame Coco" by Lorenzo Marconi.

- 2016: 1st place - best costume on the topic: “I CARRETTI SICILIANI” by Salvatori Occhipinti and Gugliemo Miceli from Ragusa and Scicli, and 1st place - most beautiful costume: “I BAGNANTI DI SENIGALLIA” by Anna and Lorenzo Marconi from Senigallia.

- 2017: 1st place: "Il Signore del Bosco" by Luigi di Como

- 2018: 1st place: "L'amore al tempo del Campari" by Paolo Brando

- 2019: 1st place - best costume on the topic: "I Bambini della Luce" by Horst Raack, as well as 1st place traditional costume: "Matrimonio all 'Italiana" by Borboni si Nasce, and 1st place most original costume: "Paguri" by Nicola Pignoli and Ilaria Cavalli

In 1999 the Festa delle Marie was revived under the direction of Bruno Tosi and it is now part of the Venetian Carnival as a beauty contest organized by the Associazione Venezia è ... (Storia arte cultura).

Masks and costumes

During the Carnival in Venice, the half mask is mainly worn, which only covers part or half of the face . Originally it was used as a theater or speaking mask, which - for example in the Italian Commedia dell'arte - made it easier for actors to speak loudly and clearly. During carnival it also had the advantage that you could eat and drink without any major difficulties. The Bauta , a full mask with a protruding chin, was common among men and women.

How people dressed in costumes in the 18th century can be found in a document entitled "Different ways to dress up in carnival ...". The many options listed include, for example: angler with a fishing rod, doctor of medicine, lackey , lawyer with files, devil, butcher, astrologer , hunter with dummy rifle . In between were the classic masks, the harlequin with his patched suit, the clever Colombina , the imaginative servant Brighella , Pulcinella (with a question mark made of macaroni ), the vain dottore , the boastful captain .

Wearing masks was also common in Venice outside of Carnival, for example in the two weeks before Pentecost and then until mid-June. Later masks were also allowed from October 5th until the beginning of the Christmas novena on December 16th. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe noted during his trip to Italy on October 4, 1786: “I had the desire to buy a Tabarro with the apartments, because you are already wearing the mask.” For all important events such as official banquets and other celebrations of the Serenissima were attended with mask and cape. Furthermore, gamblers masked themselves to protect themselves (from their creditors) and impoverished nobles while begging on the street corner.

In addition to the traditional masks that also appeared in the plays performed during Carnival time, there were also other masks and disguises. A mask costume that was worn almost all the time and that granted real anonymity was the baùtta , a disguise for both women and men, which was also allowed outside of the carnival at the specified times. It consists of a black cape made of silk or velvet, which has a hood that is open at the front and leaves the face free. A black or white mask ( volto or larva ) is pulled over the hood, covering the face only up to the mouth. The typical Venetian three-cornered hat is worn over the mask .

A popular carnival mask for women was the so-called moretta . It is small, oval and originally made of black velvet. It is held in the mouth so that the wearer cannot speak.

The making and selling of masks became an extremely profitable business over time, and not just within the city. Countries all over Europe were supplied with the well-known and popular Venetian masks. The mask makers or "Maschereri" even had their own statutes from 1436 under the Doge Francesco Foscari . They belonged to the painters' guild and were supported by draftsmen who designed faces in a wide variety of shapes and executed them with great attention to detail. Until 1820 there was an extensive mask production in Venice, which then slowly succumbed to the cheap French competition. In 1846, 75,000 to 100,000 masks were still made in Venice (Zorzi Austria's Venice, pp. 263, 351).

See also

Remarks

- ↑ Giuseppe Tassini: The venetian festival - I giochi popolari, le cerimonie religious e di governo illustrate da Gabriele Bella. Firenze 1961 p. 127; Ignazio Toscani: The Venetian Society Mask. An attempt to interpret their form, their origins and their function. Diss. Saarbrücken 1972 p. 226. Statements that Napoleon banned the Cologne Carnival, from which it is sometimes deduced that such a ban applied to all areas occupied by Napoleonic troops - consequently also to Venice - are imprecise. The French occupiers forbade Carnival in Cologne on February 12, 1795, but allowed it again in January 1804. The ban apparently only affected the street parades, because people still enjoyed themselves at masked balls. ( Ernst Weyden : Cologne on the Rhine fifty years ago. Cologne 1862; Reprint: Cologne on the Rhine one hundred and fifty years ago. Cologne 1960 p. 137 )

- ↑ In 1797 the French were not in Venice during Carnival. They occupied the city on May 16, 1797 and withdrew in December. Napoléon himself only came to the city during the second French period of rule over Venice in 1806. There are numerous accounts of Carnival celebrations in Venice during the 19th and 20th centuries. The Carnival was forbidden by the Austrians in 1798, wrote Henry (Ette) Perl (Napoleon I in Venetia. Leipzig 1901 pp. 173 and 210ff), while the French troops, who in 1814 in view of the approaching Austrians and increasingly because of the French looting enraged masses imposed a state of siege, nor tolerated carnival parades and freedom from masks.

- ↑ In 1859 the Fenice closed "for economic reasons" (see Andreas Gottsmann: Venetien 1859–1866. Austrian administration and national opposition. Vienna 2005 p. 419). It was stated: “We will not open the Fenice again until Vittorio Emanuele is also our king. Hopefully it won't be long. ”(Quote from Eugen Semrau: Austria's traces in Venice. Vienna / Graz / Klagenfurt 2010 p. 113) Even in the run-up to the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861, resistance to foreign rule increased again Had been brutally suppressed in 1849. "Until the annexation of Veneto to the Italian national state, according to the opposition's plan, public life, from popular amusements to theater performances and political representations, should remain completely paralyzed." (Gottsmann p. 426). "Participation in public amusements for the ongoing Carneval was annotated in advance", St. Mark's Square was demonstratively emptied when the Austrian military music played, and the pro-government press was barely read (Gottsmann, ibid., Reports from Police President Straub from 24. January 5th and February 5th 1860). The Austrian authorities could do little to counteract passive resistance such as theater closures. “There are numerous examples of the Veneto theaters, on whose behavior the party of the revolution exerted direct and indirect influence. A characteristic policy is being pursued here: the Italienissimi, the supporters of the Unification Party, some of whom are shareholders of the theaters, prevent their activity. As far as they are civil servants in the Imperial and Royal Venetian Gubernium, they do not try to expose themselves in any way and only prevent new seasons in the theater, for example in the Teatro Fenice in Venice or in the Teatro Concordia in Padua, with economic reasons. Only at the moment of the impending war, the state of siege, in 1866, do these forces become openly active ... The liberal opposition also interfere in the affairs of the S. Benedetto Opera Theater . ” Theater history of the Austrian imperial state Vienna 1967 p. 10f) The kk PolizeiRath Germ (deciphering of the name uncertain) reported u. a. to Vienna (all information according to the documents printed by Dietrich p. 23ff): “For a long time the local audience had been concerned with the question of whether the Fenice Theater should be reopened next summer or Carneval ... Nevertheless, the ill-minded offered how usually everything to thwart the reopening of the theater. “In 1864 36 of the present shareholders of the Societá del Gran Teatro La Fenice voted against and only 2 for a reopening, on April 30, 1865 40 and 44 (different information) were against and 17 for an opening, on December 17, 1865 43 against and 26 for, on April 8, 1866 57 against and 19 for (reports of May 1, 1865, February 11, 1866, April 9, 1866).

- ↑ Gilles Bertrand, Histoire du carnaval de Venise, XIe-XXIe siècle, Paris 2013, pp. 237-310

- ↑ Lord Byron wrote on December 19, 1816, "The carnival begins in a week - and with it the mummified masks of the masks" and he has "a good box (in the Fenice) for the carnival". On January 30, 1825, Tommaso Locatelli reported in a feature section about the carnival parade on the Riva degli SchiavoniI (quoted by Alvise Zorzi: Österreichs Venedig. Düsseldorf 1990 p. 55). In 1830 Otto Ferdinand Dubislav von Pirch saw a “masked procession, Spaniards with their ladies, twenty couples, very well costumed”. George Sand saw the Carnival from his window on March 6, 1834. On December 28, 1851, Effie Ruskin wrote to her mother: “Yesterday was St. Stephen's Day, on which the carnival began and La Fenice opened.” (John and Effie Ruskin: Briefe aus Venice. Stuttgart 1995 p. 64) And On February 19, 1852, John Ruskin wrote to his father: "The Austrian officers held their last carnival ball yesterday, and because it was supposed to be very festive and masquerading, I thought that Effie should see it." (Ibid. Pp. 74f ; similarly a year later p. 76; these remarks by the Ruskins refer, as the text clearly shows, to official carnival events organized by the Austrians) Shortly before his death in 1883, Richard Wagner went to the carnival with his children. “Shrove Tuesday fell on February 6th (1883). - - The St. Mark's Square swam in its sea of rays in the literal sense of the word ... Countless masks and mask trains moved with Italian liveliness and the obligatory use of voices among the Procuratien, crowded into the café, performed their extempore comedies in the middle of St. Mark's Square. "( Henry (ette) Perl: Richard Wagner in Venice, Augsburg 1883, Reprint oO o. J. (2010) p. 108f. This book is one of the main sources of John W. Barker (Wagner in Venice. Rochester NY 2008), the S . 119 noted the same.). The Venetian historian Alvise Zorzi wrote in 1985 in his book Venezia Austriaca (German: Austria's Venice): In 1846 "75,000 to 100,000 copies" of masks were produced in Venice (p. 263). He named p. 351–353 some carnival societies, "organized mask groups" (Ibid. P. 351; on Carnival 1851/52 p. 114–116).

- ↑ Birgit Weichmann: Flying Turks, beheaded bulls and the power of Hercules. In Michel Matheus (ed.): Fastnacht / Carnival in European comparison. Stuttgart 1999 p. 195f

- ↑ "The art of masks is old and new at the same time." It was almost extinct, "says Guerrino, pulling a tattered magazine from 1978 from the shelf in which three young artists with long hair built classic men's masks Because they needed money, the trained sculptor and his friends made the first designs for a theater troupe. An embarrassment. Shortly afterwards, the Venetian Carnival, banned by Napoleon, was taken out of the prop room of history and Maestro Lovato was appointed its master of ceremonies. "( Spiegel Online from March 7, 2006 | 05:56; http://www.spiegel.de/reise/staedte/venedig-karneval-der-kaeuze-a-404631-2.html )

- ↑ The oldest documents only mention pigs (1222) and bread. The bull as a tribute can only be documented from 1312 (Heinrich Kretschmayr: Geschichte von Venedig. Vol. I. Gotha 1905, 1920, Stuttgart 1934. Darmstadt 1964, 2nd reprint of the Gotha 1920 Aalen 1986, reprint oO o. J. ( 2010) p. 251). In 1296 the fat Thursday was made an official holiday.

- ↑ See also Ignazio Toscani: The Venetian Society Mask. An attempt to interpret their form, their origins and their function. Diss. Saarbrücken 1972 p. 226. The Toscanis study deals in detail with the Venetian concept of anonymity; the research blog http://www.licence-to-mask.com contains further information

Individual evidence

- Legislazione veneziana in materia di teatro e spettacoli , in: Michela Dal Borgo (ed.): Carnevale a Venezia. Serenissimi Teatri. Attività teatrale a Venezia tra legislazione e spettacolo (secoli XI a XIX) , catalog for the exhibition from February 13 to 21, 2012

literature

- The Venice Carnival . Editizioni Storti, Venice 1985/1986, ISBN 88-7666-258-8 .

- Meyer's Encyclopedic Lexicon . Bibliographical Institute, Mannheim / Vienna / Zurich 1973, Volume 13, p. 478.

- Meyers Konversationslexikon . Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna, 4th edition, 1885–1892, Volume 9, p. 548.

- Auguste Bailly: La Republique de Venise. Fayard, Paris 1946.

- Ettore Beggiato: 1809: l'insorgenza veneta. La lotta contro Napoleone nella Terra di San Marco , Il Cerchio, Rimini 2009. ISBN 88-8474-210-2

- Marion Kaminski: Venice - Art & Architecture . Könemann, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-8331-1308-1 , p. 440.

- Michael Matheus (Ed.): Fastnacht / Carnival in European Comparison (Mainz Lectures 3), Franz Steiner Verlag, Mainz 1999, ISBN 978-3-515-07261-8 .

- Sandra Maria Rust: Venice and the Carnival. In: Matthias Pfaffenbichler (curator): Venice - sea power, art and carnival. Schallaburg Kulturbetriebsgesellschaft, Schallaburg 2011.

- Henry (ette) Perl: Napoleon I in Veneto. Heinrich Schmidt & Carl Günther, Leipzig 1901

- Henry (ette) Perl: Richard Wagner in Venice - mosaic pictures from the last years of his life. Augsburg 1883, reprint oO no year 2010.

- Rolf D. Schwarz: Carnival in Venice. Harenberg, Dortmund 1983, ISBN 3-88379-422-8 .

- Angelica Tarnowska: The festivals in Venice. In: Alain Vircondelet (ed.): Venice and its history. The art to live. Paris 2006.

- Giuseppe Tassini: Feast of Spettacoli. Divertimenti e piaceri degli antichi veneziani . Reprint of the 1890 edition, Venice 2005.

- Ignazio Toscani: The Venetian Society Mask. Saarbrücken 1972.

- Alvise Zorzi : Austria's Venice. The last chapter of foreign rule 1798 to 1866. Düsseldorf / Hildesheim 1990.

- Alvise Zorzi: Grand Canal. Biography of a waterway. Claassen, Hildesheim 1993, ISBN 3-546-00057-9 .