Vitale Michiel II.

Vitale Michiel II (* beginning of the 12th century in Venice (?); † May 28, 1172 there) ruled Venice from 1156 until his assassination. According to tradition, as the state-controlled historiography of Venice is called, he was the 38th Doge . He is also the last doge to be elected by the popular assembly.

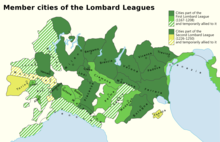

The Byzantine emperor Manuel I Komnenos tried to break the economic domination of Venice that had existed since 1082 by granting the Republic of Genoa far-reaching privileges. At the same time he fought against Venice's supremacy in the Adriatic , especially in Dalmatia , where Hungary also played an important role, and Ancona . In Italy the Doge supported Pope Alexander III. and the Lega Lombarda in the fight against Frederick Barbarossa , who in turn was supported by Genoa and other Ghibelline cities .

When Venice refused a Byzantine emperor's request for naval aid for the first time in its history in 1167, the first breach occurred. In 1168 a Venetian fleet attacked Ancona. The final break came on March 12, 1171 when all Venetians in the empire were arrested. The Doge, who thereupon led a large navy against Byzantium, which achieved considerable success in the Aegean , allowed himself to be held off too long in negotiations. So the fleet had to winter on Chios . Weakened by an epidemic , the fleet finally had to return home without any results. In Venice, too, numerous people died of the illness they had brought with them; the number of deaths was estimated at 10,000. Vitale Michiel was finally murdered on May 28, 1172 not far from the Doge's Palace .

Origin, family

The Michiel family belonged to the so-called twelve apostolic case vecchie . Twelve procurators have emerged from it. Vitale Michiel II. Was the third doge from the family after the two doges Vitale Michiel I (1096–1102) and Domenico Michiel (1118–1130). Taddea Michiel became the wife of Giovanni Mocenigo in the 15th century .

It has often been assumed that Vitale was a son of the aforementioned Dogen Domenico, who resigned in 1129/30, but there is no evidence of this in the sources. The descendants of Vitale Michiel II lived in the municipality of San Giuliano , so that a relationship with the local branch of the large family is closer, to which the iudex Andrea, called "maior", who died around 1125, belonged. Because of this, it cannot be determined with certainty which branch (ramo) of the Michiel family Vitale belonged. The few clues also cannot be related to the Doge with sufficient probability. It is unclear who was the Vitale who signed the trade treaty with Constantinople in 1147 .

From 1157 bonds are documented that Vitale Michiel issued privately in return for guarantees in the form of land or salt pans in which sea salt was extracted. This happened in particular in the Chioggia area on the southern edge of the Venice lagoon . In some cases, these bonds were not repaid, so the guarantees fell to the borrower. This grew his property in the south of the lagoon, as did ordinary purchases. This property passed to his male heirs after the Doge's death.

Vitale Michiel was married to a Maria whose origin is unknown. The couple had two daughters, namely Agnese, who married Giovanni Dandolo, and Richelda, who married into a count's house in Padua , and therefore appears in the sources as "Contessa". Up to 1159, the two sons, namely Leonardo and Nicolò, whom the Doge kept in material dependence for a long time, but also in legal dependency, are also recorded. This state of affairs lasted until February 1171, when he released the sons from their dependency and transferred part of the immovable property to them.

In 1165 Leonardo had a dispute with the Count of Zara , with Domenico Morosini, who claimed half of the county of Ossero , which had been allocated to him by his father of the same name. Leonardo, for his part, won the county through Michiel's lifelong investiture. With the approval of a iudex, the latter agreed with the son insofar as, unlike his opponent, he had demonstrably paid a significant sum for the investiture. Control of the islands of Cherso and Lussino remained in his hands until Leonardo's death . According to the Doge's will, he married a princess, daughter of the Serbian Count Desa .

In 1174, the two brothers dissolved the joint trading company and sold mobile and immobile values that they had previously held together. Leonardo appears in 1175 in an embassy from Doge Sebastiano Ziani , which was negotiating in Constantinople. He also appears as a witness in a privilege of Frederick Barbarossa for the monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore from the year 1177. Leonardo made his will in 1184, whereby the abbess of San Zaccaria was appointed administrator. He bequeathed a large part of his property to the monastery. He died in December of the same year. His brother Nicolò outlived him by about a decade.

Doge's Office

Vitale Michiel succeeded his predecessor Domenico Morosini, who died in February 1155, as Doge. He is the last doge to be elected by the popular assembly, the arengo . With the choice of his successor, the Doge was initially determined by the Small Council .

In the election year, the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos granted Venice's trade rival, the Republic of Genoa , far-reaching privileges in order to counterbalance the economically overly dominant Venetians. As a result, Venice entered into an alliance with Pisa for the first time to fight their mutual rival. This alliance, however, had no tangible consequences. On the other hand, the custom established itself permanently , never again to indicate the name of the emperor on the silver coins, the denarii , but only that of the doge.

But first the new Doge had to deal with problem areas that his predecessor had not solved. This was particularly true of Dalmatia , where Venice had controlled the north since the 1130s, Hungary the central section of the coast and Ragusa the south. The latter was theoretically still under Constantinople. In addition, there was the conflict between the bishops of Zara and Spalato , whose metropolitans had the ambition to bring all of Dalmatia under their obedience. This constellation became explosive because the Doge and the King of Hungary stood behind them as secular lords. Pope Anastasius IV had already raised Zara to the rank of archbishopric in 1154 , but placed the dioceses of Arbe and Ossero under the patriarch of Grado . His successor Hadrian IV now placed the Archdiocese of Zara under the jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Grado. The local patriarch Enrico Dandolo also became the metropolitan of all of Dalmatia, with which he was allowed to consecrate the archbishop , even if the delivery of the pallium remained with the Pope. Enrico Dandolo was thus subordinate to the ecclesiastical area up to the borders of Ragusa. The King of Hungary did not accept the new conditions at all, but triggered an uprising in Zara. His followers drove out the Venetian governor Domenico Morosini, who had ruled there with the title of Conte . It is unclear what the countermeasures looked like, but the Doge reacted in 1156. Apparently the Venetian forces suffered a defeat. An initiative in Rome resulted in Pope Hadrian IV writing directly to the Doge, confirming the patriarchal supremacy over the Archdiocese of Zara. But this remained a mere claim that could not be enforced. Vitale Michiel planned an expedition against Zara, where he required the Venetians who were staying in the Byzantine Empire to appear in Venice by Easter 1159, i.e. by April 12th. But those who were in the Crusader States were supposed to return by September. Eventually, those who were unable to return in time because of their business were fined. Among them was the celebrated trader Romano Mairano . In autumn the fleet appeared before Zara, the city was conquered and the Hungarian garrison had to withdraw. The residents had to renew their oath of allegiance to Venice, the city government again went to a Venetian, namely Domenico Morosini. It was at this time or a little later that the Doge appointed his son Leonardo to be the Count of Cherso and Lussino, his son Nicolò of Arbe. Venice thus took over direct control of the coastal cities, with the county of Veglia going to the sons of the late Conte Doimo, namely Bartolomeo and Guido, who were already vassals of Venice.

In Italy the Doge supported the new Pope Alexander III elected in 1159 . in the fight against Friedrich Barbarossa. This isolated Venice's trade from the empire and forced a greater turn to the east. Conversely, the new hostility of the Roman-German emperor led to plans to subdue the lagoon city. At the beginning of 1162 the combined troops of Padua , Verona and Ferrara forced the abandonment of Cavarzere , but a fleet, which was going up the Po , put the attackers to flight. The castle was recaptured, then the cities of Adria and Ariano sacked. Probably in the same year the Patriarch of Aquileia, Ulrich von Treffen , besieged the island city of Grado . The Doge immediately ordered all available ships to go north, the patriarch's troops were put to flight, the patriarch himself and some of his followers were taken prisoner in Venice. On the way back, the fleet repulsed another attack by the Trevisians on Caorle . The patriarch was released from captivity for an annual tribute. After the military attacks of his allies had failed, Barbarossa allied with Pisa and Genoa, with Genoa pestering the Venetian trade until this city had regained the friendship of the emperor. The Doge responded by launching a diplomatic initiative to detach some cities from the Imperial Union.

In 1164, on the initiative of Venice, the Lega veronese , the League of Verona, to which Verona, Padua and Vicenza merged, followed by Treviso and smaller cities in the vicinity of Venice. Venice took the side of the league and secured it financially. For this purpose, the Doge had to pledge the proceeds from the Rialto market in June 1164 against a voluntary loan of 1150 silver marks. In 1167 the large Lombard municipalities and the Lega veronese became the Lega Lombarda . For Venice the critical moment was already over, because until 1177 it was no longer involved in the fighting between the empire, the communes and the papacy. Pope Alexander III explicitly thanked the Doge for his support in 1165. The Pope granted the Opera di S. Marco the income from the parishes of the saint, namely from San Giovanni d'Acri and from Tire , which the Doge had already transferred to the Bauhütte the year before . 1167 also vacated Bohemond III. of Antioch granted the Venetian merchants privileges in his sphere of influence. This secured the privileges in the Principality of Antioch and in the Kingdom of Jerusalem .

However, there were violent disputes with Byzantium under Emperor Manuel I. Venice had not supported him in his fight against Hungary, but Ancona had supported Ancona , Venice's main rival within the Adriatic. The contrasts were so great that Venice at the end of 1167 refused the Byzantine ambassadors' request for help from the navy for the first time in the event that a war against the Normans broke out. This decision had as sharp an anti -Byzantine point as the marriage of Leonardo to a daughter of Desas, the Grand Zupan of Rascien. He fled to the Hungarian court in 1166 to evade Manuel's rule. The marriage of the second Doge's son Nicolò, that Conte von Arbe, with a Hungarian princess, a daughter of King Stephen III, aimed in the same direction . In the same year 1168 Vitale Michiel led a punitive expedition against Ancona, allied with Manuel. Nevertheless, the traditional ties between Venice and Constantinople were not yet completely broken, because the Doge could still grant privileges to monasteries and churches that had goods and rights in the Byzantine Empire.

It was not until March 12, 1171, that the rupture occurred - nevertheless completely surprising - when Emperor Manuel ordered the arrest of all Venetians in his empire. Their property has been confiscated. Only a few Venetians escaped, such as those who managed to set out from Constantinople on the ship of Romano Mairano , which set sail for San Giovanni d'Acri. The reasons for this surprising, ruinous act for many small traders, are far from clear. According to Venetian sources, it was an act of revenge by the emperor for the Doge's refusal of 1167 to provide military aid against the Normans, or sheer greed to usurp the property of the thousands of Venetians. Byzantine tradition, on the other hand, emphasizes the arrogance of the Venetians towards the Empire, the enormous number of Venetians in the capital, which led to huge social problems, and their refusal to provide adequate compensation for an attack on the Genoese quarter in 1170. The Historia Ducum knows that the imperial invitation that had been issued earlier had an enormous pull on the Venetians: “Exierunt autem anno fere viginti milia Venetorum in Romaniam”. It can be assumed that the number of 20,000 Venetians is an exaggeration. But it must have been so large that its imprisonment must have made it extremely difficult to build and equip the fleet.

News of the catastrophe quickly reached Venice, where, despite the decision to first send off a negotiating delegation, the war advocates dominated. Finally, in September 1171, a fleet of 100 galleys headed south under the command of the Doge.

On the way ten more galleys, which provided the cities of Istria and Dalmatia, joined the fleet. However, 30 ships were hijacked before Traù , which Byzantium had remained loyal to. Its walls were partially demolished after the city was captured and looted. The remaining ships went to Ragusa, which was forced to accept a Venetian governor after a few days of siege. Then the fleet penetrated into the Aegean Sea , landed on Euboea and the capital Chalkida began to be besieged. The local Byzantine commander offered to return all goods if an embassy was sent to Constantinople. The Doge then sent the Bishop of Iesolo , Pasquale, who spoke Greek, and Manasse Badoer to the imperial court. The siege of Evia was lifted and the fleet captured Chios , where they wintered. From there, the coastal cities of the empire were terrorized. The two ambassadors did not succeed in gaining access to the emperor, so they were called back, even if they had received promises about the possibility of a peace treaty. The imperial representative traveling with them made promises in this regard. So the two ambassadors went back to the capital, reinforced by a third.

But while they were negotiating there, an epidemic broke out in the Venetian camp . A thousand men died in a short time. Meanwhile, an imperial fleet approached the island of Chios in the first days of April 1172. The occupiers then drove to Panagia , but there the epidemic claimed numerous other victims. Now the ambassadors returned - again empty-handed. Once again the Greek traveling with them suggested an embassy trip. This time Enrico Dandolo , who later became the Doge, and Filippo Greco drove to Constantinople - according to the (probably inaccurate) legend, the emperor had the envoy Enrico Dandolo blinded during this visit. The decimated fleet retired to Lesbos back to Lemnos to achieve, but forced storms they so once Skyros to go, where to Easter celebrated (April 16, 1172). The exhausted Venetians finally forced the Doge to order to return. The fleet was repeatedly attacked by Byzantine ships on the way back. The large fleet remained without any tangible success, and the returnees also infected those who remained in Venice, so that further victims were to be lamented.

After the failed punitive expedition, the Venetian councilors, who had previously driven the Doge to war, looked for someone to blame for the debacle in which around 10,000 men had died. They assigned all the blame to the Doge and incited the people against him. Only a few days after his return, the Doge was to be criticized in a public meeting on May 28, 1172 in the sharpest possible way for his leadership of the navy; his councilors had failed him. The Doge was murdered by a man named Marco Casolo before the trial opened near San Zaccaria . He was later executed. The sources give no indication of contract killing. The murdered man was buried in San Zaccaria, followed by the aforementioned Sebastiano Ziani in office.

Twelve documents have survived from Vitale Michiel II's term of office, six of which have been preserved in the original. Three of these documents are from the year 1160, the others from the years 1161, 1164 and 1170.

reception

From the late Middle Ages

The Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo from the late 14th century, the oldest vernacular chronicle of Venice, represents the operations as well as Andrea Dandolo on a long common at this time, largely dominated by the Doge level is - they even make the time frame for the entire chronicle. “Vidal Michaeli” was raised to the rank of doge “a clamor de tucto el povolo”, ie upon acclamation of the whole people. This is immediately followed by the description of the conflict with Emperor Manuel, who wanted to destroy the "insula de Cecillia" - not so much the "island of Sicily" as the Norman Empire ("agnençar"). The emperor, out of anger at the behavior of the Venetians in “Ystria”, “tucti li Venetiani che erano nelle sue parte sustene”; so he had all the Venetians in his kingdom seized or imprisoned. The Doge compared the relationship with his predecessor, who was an ally of the empire - the author calls him “aiuctor” - and he instructed that 100 galleys should be built within exactly 100 days (“in C giorni, ne plù ní meno”) and should be equipped (“fabricade et armade”) “per una perpetual fama per luy”, that is to say for his eternal glory. He took this fleet to Greece, where he caused great damage to the land and the emperor's ships, and then went to Chios to besiege it. The author of the chronicle claims (p. 64) that Emperor Manuel, who had nothing to oppose the Armada, gave the island's inhabitants the secret order to poison the island's drinking water (“et secretamente mandò a gli habitanit del'isola de Chio che lle ague tucte de quel luogo fusseno atossegade, et cusi fo facto. ”) A third of the ship's crews died from it, including all members of the House of Iustiniani (“ Iustignan ”). The Doge then wanted a young monk in San Nicolò di Lido , who was the last male survivor of this old family, to leave the convent to marry. All Giustiniani were descended from this and his wife. When the fleet reached "Sclavania" on the way back to Venice, where Trau and Ragusa had gone to Manuel, the Doge Ragusa won back, which he reported to "Rainer Zanne". Zara, too, expressly in rebellion since MCLVIII, was subdued for the third time by a fleet under "Domenego Moresini", after which the author describes the battles for Grado. The patriarch "Ordellicho", who was held captive, promised redress in the end. An agreement was reached, "è stado di grande dispregio", which thus abandoned the patriarchs to contempt: every year he and his successors were supposed to deliver a bull ("tauro"), twelve wild boars ("XII cenglari") and bread (the Author describes them as "bruççoladi", "Kringel" as the editor translates). The bull stood for the “ferocità” of the patriarch, which symbolically ended with the decapitation of the bull, the pigs stood for the clergy, the bread for the “Castellani”. As the author emphasizes, the associated festival is still celebrated every year, and will do so for all eternity at the patriarch's expense (p. 65). In the “Sala dei Segnor” a game has been performed during the night that stands for the destruction of the castles in Friuli , with the focus on “Duxe et la Ducaresa”. - Only then does the author mention the “imprestidi”, the bonds that were issued, plus another fleet (“un'altra armada”) that sailed to Constantinople under the leadership of the Doge. The emperor, who feared the power of the Venetians, had sent envoys to the doge to negotiate a peace. Any damage should be made good, and so be it. The assassination attempt of 1172 remains puzzling in the chronicle. The Doge went to San Zaccaria at Easter, as his predecessors were used to, and there became "d'alguni so 'citadini et iniqui homeni fu morto", so he was from killed any of its citizens and unscrupulous men. "Vidal Michiel" was buried in San Zaccaria after 17 years of reign.

Pietro Marcello said in 1502 in his work, later translated into Volgare under the title Vite de'prencipi di Vinegia , “Vitale Michiele Secondo, successe nel Prencipato l'anno MCLVI.” In some respects his vite deviates from the earlier representations, some are smoother described, in other places he inserts differing opinions. The Pisans became 'friends' (“amici”) of the Venetians who protected the Pope against Frederick I (“presero la protettione di Papa Alessandro Terzo contra Federico Barbarossa”). Paduan, Veronese and Ferrarese plundered "Capo d'Argere", but the Venetians drove them away, who now covered the Adriatic with fire and sword ("misero a ferro, & fuoco"). When "Vlrico Patriarca d'Aquilegia" occupied Grado, he was captured by the Venetians with twelve clerics and 'with many others of the noblest'. For an annual tribute from a bull and ten (!) Pigs. In the eternal memory of these events, these should be killed, especially the people. But there were some, according to Marcello, who assigned this tribute to the Doge " Angelo Particiaco ". For him, Emperor “Emanuel” started the war with Venice. On the pretext that he needed support against the attack by Wilhelm of Sicily, to whom he had promised his daughter to be his wife, he asked Venice for help. As expected, the Venetians refused this because they had made peace with the king. As a result, the emperor believed he had a "quasi legittima occasione di muover guerra", an "almost legitimate opportunity to start war" (p. 71). Exactly the opposite of Caroldo, who completed his work thirty years later, the emperor only now conquered the cities of “Spalato, Ragugia, e Traù”. With a "malitia Greca" he lured the Venetians back into the empire, who actually returned "per desiderio di guadagni" - they followed the desire to win. They trusted in their old services against the empire. To 'renew friendship' the first embassy traveled to Constantinople, but no sooner had “Sebatian Ziani, & Orio Malipiero” arrived than the emperor had all Venetians arrested and “confiscò” “all money and all things”. The news of this reached Venice through refugees. With Marcello it was the “città” that gave the order to build a fleet, so that 100 ships were launched in 100 days, according to the author with “meravigliosa prestezza”, with “fabulous speed”. In contrast to Caroldo, no fleet from Dalmatia appears here, but Traù was also destroyed here, and Ragusa was also “mise a sacco”, ie plundered. There the imperial tower with its insignia was torn down (p. 73). The “governatore” of Negroponte persuaded the doge to send new envoys to the capital, so that “Manase Badoero” also traveled with him. The fleet now drove to "Scio", the island fell to the Venetians. Marcello describes in a lengthy manner how Manuel held out the ambassadors. When they returned unsuccessfully, the "crudelissima peste" broke out. The rivers from which the Venetians got their water were, as Marcello said some said, poisoned by the Greeks. The Giustiniani legend, according to which the said monk and the last male member of the Giustiniani family were allowed to marry in order to save their continued existence, tells Marcello that it is thanks to her that the presence of " Lorenzo Giustiniano " (1383-1456) is due to her as well as from Leonardo and Bernardo, his son (p. 74 f.). At Marcello there is no questioning of the Doge's people, rather the fleet is returning on its own in the face of the catastrophe. With the return, “molte migliaia di persone” died, “many thousands of people” died. When the people were called to deliberation, they all blamed the Doge and called him a “traditore della Republica”, a “traitor to the Republic”. He had gambled away the victory, lost the fleet to the emperor and, what was worse, exposed it to destruction by the poison. So everyone screamed for his death. The poor doge ("il povero doge") could not apologize, he saw that his life was in danger and secretly fled the "consiglio". There he met 'I don't know who' (“non sò chi”) who inflicted a huge wound on him, on which he “miseramente morì” in the 17th year of his “Prencipato”. The whole people celebrated his funeral ("Il suo mortorio fu celebrato da tutto 'l popolo"). In order to calm the unrest and to prevent an attack on the Doge in the future, the Council of Ten is said to have been set up, as some say, according to Marcello. Others say, according to the author, that the Council of Forty was set up to elect the Doge, which would elect the Doge in the future.

Daniele Barbaro, clerk of the republic from 1512 to 1515, summarized the catastrophe of 1171 as follows: "fù questa offesa grandissima et tanto universale ..., che non vi fù casa che non sentisse parte di quel danno". Without exception, all cases , all important houses, were affected by the catastrophe.

According to the chronicle of Gian Giacomo Caroldo , “Vital Michiel di questo nome IJ” was elected Doge in the year “MCLVI”, ie 1156 (“successe per elettione”). First he found a compromise with Pisa, then the author describes the battles between the patriarchs of Grado and Aquileia, between the emperor, "Antipapa" and the Pope, as well as the northern Italian cities. It was Cavarzere looted when the enemy troops were surprised and the Venetians Adria fell into the hands. Ultimately, “Ulderico Patriarcha d'Aquilegia” and twelve clerics were taken prisoner near Grado. The "Duce vittorioso", the 'victorious doge', took them to Venice. The said tributes should be delivered to every “Giovedi Grasso” (p. 140 f.). The doge allowed 'those of Arbe' to choose their conte through four of their 'cittadini', and the doge again confirmed this. According to the author, the Doge's son, "Nicolò Michiel", was elected to be the Conte a little later, who in turn was confirmed by the father. It appears in the privilege “che da loro sin al presente giorno viene conservato con il suo bollo di piombo”, which, together with its lead seal, was preserved in Caroldo's time. Obviously important for the author is the conclusion that he expressly draws from this, namely that, as this document shows, those who believed that Pope Alexander allowed the Venetians to use lead seals are mistaken. It could be that the Pope only confirmed what the Doge did before (p. 141). Caroldo probably had all the documents in the Dogenkanzlei. - King Stephen of Hungary feigned friendship with the Doge ("fece simulata amicizia") and offered a marriage between Maria (his niece?) And his son Nicolò. When Stephan's “mal'animo” could no longer be hidden, he marched to Dalmatia and conquered Spalato, Trau, Sebenico and other places, a process that did not occur with Marcello thirty years earlier. The tsarese, who could not stand the subordination of their archbishop to the patriarchs of Grado ("non potendo patir"), "ribellorono" against the Venetians. They drove out the son of a dog "Dominico Moresini" and hoisted the flag of the King of Hungary ("levorono l'insegne del Re d'Hungeria"). The fleet of 30 Venetian galleys turned back in the face of the strong crew. In addition, Caroldo mentions a defeat against the Anconitans in which five of the six galleys were lost (p. 142). In the 15th year of his dogat, Vitale Michiel had his son Domenico attacked with a "potentissima armata" Zara. After long fighting, the Hungarians withdrew and the Tsarese submitted (“facendo deditione liberamente”). The son of a dog took 200 tsarese hostage. Now, in consultation with Stephan, Emperor Manuel subjugated the coastal cities of Spalato, Trau and Ragusa "et quasi tutta la Dalmatia". However, the emperor pretended that the Venetians were as safe in his empire as they were in their own country. According to Caroldo, the Doge remembered the old friendship between the empire and Venice and therefore granted permission to trade in his empire. He also sent the ambassadors Sebastian Ziani and Orio Mastropiero to the court. The merchants, also driven by the hope of profit at Caroldo (“mossi detti mercanti dal guadagno”), felt safe and went on numerous ships to various parts of the empire. At the court they had solemnly sworn not to have bad intentions (“fece loro solenne giuramento non haver alcun mal proposito contro Venetiani”), but secretly (“secretamente, con la Greca perfidia”) the emperor gave orders on March 12th , in the 16th year of the Dogate Vitale Michiels, to arrest all ships and traders ("ritenere") and to send them all to Constantinople. The mass arrest was by no means surprising for Caroldo, as other authors believed, but a consequence of the conflict over Dalmatia and Ancona. Nevertheless, the doge tried to stay on the path of peace ("la via della pace") and to summon an embassy. But when he heard the reports brought by the Venetians who had managed to escape on 20 ships, the Doge and the “Senato Veneto” decided to go to war. Order was issued to build 100 galleys ("finir") and 20 ships, a fleet that was subordinated to the Doge himself in order to avenge himself for the injustice suffered ("per vendicarsi della ricevuta ingiuria"). His son " Lunardo Michiel " was supposed to stay in Venice . All Venetians were recalled by September. The cities of Dalmatia should also be ready, who contributed ten galleys. The fleet was ready after 100 days, picked up the ten galleys in question as it passed (which do not appear at Marcello's). Thirty galleys attacked Trau, which was utterly destroyed as a deterrent. Ragusa surrendered after a heavy siege, his ambassadors under the leadership of the Archbishop "Tribun Michiel" asked for mercy on their knees. When the Doge entered the city, he was received by the clergy while singing the Te Deum ; he swore allegiance, the imperial city tower was completely destroyed by order of the doge ("subito fosse ruinata"). If the Pope agrees, the archbishop should be subordinate to the Patriarch of Grado (p. 144). With the title Conte di Ragusa, "Raynier Zane" stayed in town. Before Negroponte, the Doge entered into negotiations about reparation - Caroldo does not give a reason because, according to the author, the war against the Byzantine cities had so far been waged with the greatest severity, even if Ragusa was treated more graciously than it was destroyed as a deterrent Trust. Vitale Michiel sent "Pasquale Vescovo Aquilino, il qual sapeva la lingua Greca, et messer Manasse Badoaro" to the court, that is, the Bishop of Aquila, who spoke Greek, and Manasse Badoer. Meanwhile the fleet drove to “Sio” (Chios), which submitted to winter there. When the Doge realized that his ambassadors were only being delayed, he called them back. The emperor had the ambassadors accompanied by a "nuncio" in order to find out the strength of the enemy. He persuaded the Venetians to send a new embassy to the court. The Doge wanted peace (this is how Caroldo explains his renewed indulgence), and so he sent the two ambassadors to Constantinople with Filippo Greco. Meanwhile, a disease called "pestilenza" spread, and many died with no sign of illness ("senz'apparenza di male"). Some claimed, according to Caroldo, that the emperor had poisoned the water. The Doge let the fleet go to "Santa Panaia" because he had lost faith in peace. The epidemic continued to rage there. Again the ambassadors returned with no results, and now the imperial nuncio complained for his part about the destruction by the Venetians. After summoning the “Sopracomiti et Capi dell'armata” and hearing from each of them his opinion, the Doge sent a final embassy under “Henrico Dandolo et Filippo Greco” to Manuel, who had already known about the “morbo” who have done infinite damage. The fleet went to “Mytilene” and from there to “Stalimene” and “Schiro”, where Easter was celebrated. His desperate crews now demanded a return to Venice, especially since the plague was still raging. After returning home, the disease also spread in Venice. The Doge was blamed for the catastrophe. The people's assembly came together, there were insults against the doge and death threats. Vitale Michiel "per dar luogo al popular rumore" left the palace and boarded a boat ("una barcha") to go to San Zaccaria. Back on land, he was fatally injured by a “cittadino” with a naked weapon (“arma nuda”). A priest gave him absolution. Shortly afterwards, the Doge died on May 27th in his 17th year of reign, as Caroldo dated. He was buried “con molta pompa” by the clergy and the people in the church of San Zaccaria. Finally, the author reports on the above fate of the Giustinian family and the papal permission for the monk “Nicolo Giustiniano” to marry a dog's daughter (“contraher matrimonio con una sua figliuola”). The last sentence on the Dogat reads: "Si ritrova scritto ch'a tempo di questo Duce si diede principio a far imprestiti, cagione d'universale mala contentezza contro di lui." The government bonds could thus have been an important motive for the hatred of the Doge without this being explicitly linked to the murder by the author.

The Frankfurt lawyer Heinrich Kellner , who sees the 37th Doge in the new Doge “Vitalis Michiel”, thinks in his Chronica , published in 1574, that this is the actual and short description of everyone who lived in Venice , that he “received the Hertduchy / in jar 1156 ". Kellner says that through his "help the Venediger and Pisans were tolerated with each other", they took "Bapst Alexander the third in iren protection / against Keyser Friederichen ... who attended the Aries Bapst or Antipapa Octavian". Padua, Verona and Ferrara were so encouraged “that they came together / Capo d argere attacked / and conquered.” But the Venetians “marched with their people against them ... and the enemies withdrew with horror and fear. Because then the Venedians did not find the enemy announced / they attacked the * Adrian region ”. Here Kellner does not follow the usual description that the city of Adria was attacked here, but only the area in question. Therefore he adds a marginal note , which is assigned in the text, as usual, by an asterisk, in which he relies on Piero Giustinian (p. 29r): "Petrus Justinian says / the Ferrarese region / and to / I think / also be believed / because then / if I find / no place around it / so called Adria. ”- When“ Ulrich the Patriarch or Ertzbishop of Aquileia ”conquered Grado, he was“ by Venetians / who immediately came to the neck / and in slain / captured and led to Venice with twelve thumb lords / and many other nobles ”. Here, too, after his release he had to "send an ox and twelve pigs to Venice" every year. Kellner also says restrictively: "Quite a few ascribe this to Angelo Particiatio." - For him, the sequence of actions that led to the war with Byzantium is such that Venice "refused and refused" the emperor's usual naval aid because she " kurtz had previously made peace and alliance ”with William of Sicily. Thereupon "Keyser Emanuel" ordered "to give way to all Venedian merchants outside Greece by an open mandate / also attacked the Venedians with army power / took Spalato / Ragusa / and Trau from them." The emperor pretended to have captured these cities "In order to make the Venediger in opposition to friends" - whereby Kellner expressly mentions this and the following in a marginal note "Keyser Emanuels betrayed the Venetians". Since the emperor invited the Venetians into the empire, and they trusted him because of their merits, “they sailed a lot of ships / looking for their profit / in Greece.” As soon as the ambassadors “Sebastian Ziani and Orius Malapier” had arrived in Constantinople, “then Emanuel left For one day arrest and entangle all Venedians with their ships and goods / confiscate their validity / and what they had. "Before the ambassadors came to Venice," the shouting was heard by others / who had fled out / brought / that through unfaithful to the keyser all ir people “had been arrested. In order to “calculate the shame”, the Venetians prepared a “huge armada.” “And one finds / that with wonderful agility 100 galeens have been scaffolded within 100 days” (p. 29v). The Doge himself led the fleet, which took in "soldiers from Istria or Schlavoney and Dalmatia", against Trau, followed by Ragusa with its imperial tower. The “governor” of Negroponte was frightened of “such large war equipment” and “thought of attacking the property with cunning”. Then follow the embassies, the conquest of Chios and the wintering there. But the emperor “did not give up his deceitful manner” (p. 30r), he “kept the matter open from fact to day”. "In the meantime there was a great death eyn on the ships" and "as they say / so should the Keyser poison the water / which the Venedians had to use / have". Kellner also reports the Giustiniani legend. Finally, the Doge forced "the great woe and indignation of the war people / that he went back to Venice". “Many thousands of people died there”. When the people came together for the "Rahtschlag", the Doge was given "who owes everything badly / was called a betrayed / and a flayer of the poor people / said / he had missed the best opportunity of war and victory for the Keyser", too he was blamed for the sinking of the fleet and the poisoning: “Everyone shouted about it / you should beat him to death.” The doge, threatened in this way, “lost” himself “secretly out of the assembly / crept away in S. Zacharie Kirchen / Allda met in someone / who gave him such a prank / that he died from it / in the sibent toe jar of his Hertzogthumbs. "" This Hertzog was otherwise a very pious man / all the people have confirmed his dead body. "

In his opus Venetia città nobilissima et singolare, Francesco Sansovino also counts “Vitale Michele II” as 37th Dogen, Sansovino provides an extremely shortened version of the events: Under him, Venice supported Milan, which was half destroyed by Barbarossa (“mezza distrutta”). Zara rebelled with the help of the Hungarian king, but the city was recaptured and many prisoners were brought to Venice. Because of the victory over the Patriarch of Aquileia, 'they say' the “festa del Giovedi grasso” was established. In the fight against the Greeks, 100 galleys were built within 100 days, plus 20 ships; the Giustiniani legend follows again, whereby according to Sansovino the monk "Nicolò Giustiniani" was 16 years old. He also knew that when the children grew up he returned to the monastery. Then, without any connection to the war against Byzantium and without the mass arrests, the plague entered Venice, for whose appearance the Doge was blamed and against whom one rose up. He fled towards San Zaccaria, where he was injured. After absolution he died and was buried in the church.

In the translation of Alessandro Maria Vianoli's Historia Veneta , which appeared in Nuremberg in 1686 under the title Der Venetianischen Herthaben Leben / Government, und Absterben / Von dem First Paulutio Anafesto an / bis on the now-ruling Marcum Antonium Justiniani , the author counts, deviating by Marcello, Kellner and Sansovino, "Vitalis Michieli, The 38th Hertzog". According to Vianoli, Venice was granted only a short period of peace between the agreements with Pisa and the battle with "Odoric / the Patriarch of Aquileia", which Verona, Padua and Ferrara then destroyed again. For when the Venetians had "accepted and received the Pope under their protection," this annoyed Emperor Frederick I so much that he "wound up" the cities against Venice, which encouraged them to attack, plunder and drag down Capo d'Argere ( P. 220). Venice then “devastated” the entire Ferrares area, which “drove the enemy back home with fear and terror.” The Archbishop of Aquileia had the “Hertzog immediately on the neck” after he occupied Grado to his damage would have. The prisoners were released under the said conditions. This "is a tradition / so still bit to the present day / but only on the ox / whose neck is cut off in one stroke / and the lighting of a fire of joy / in Venice is taken care of / and kept" (p. 221). Similar to the case of Barbarossa, the Byzantine emperor was angry with Vianoli at Venice's refusal to help, which had recently been allied with William of Sicily. With him, too, he snatched “Spalatro, Ragusa and Trau” from the Venetians, “so that he could win the Venetians as friends again”. So he offered them free trade in his empire through envoys, but the Venetians at Vianoli were not specifically looking for profits. No sooner had the Venetian ambassadors and traders arrived, "it was the twelfth March of the 1171st year," it was Manuel who had them "arrested". The ambassadors were allowed to return home. The “minds of the Venetians were violently bitter”, so that a fleet was launched “to avenge such disgrace” - “and as the scribes want / they should with strange agility within a hundred days a hundred galleys / and twenty other war ships have pushed into the Adriatic Sea ”(p. 223 f.). Vianoli also describes the stages of Trau, Ragusa and Negroponte. The local “governor” was completely surprised after Vianoli, but fell into a ruse. The said envoys were sent to Constantinople (this time without an explicit knowledge of Greek), but the Doge had Chios occupied "so that his weapons would not be idle". The ambassadors who had been put off had "finally got tired of waiting / and went to Chios without having done anything". Vianoli claims without qualification that the emperor had the drinking water poisoned. Vianoli believes only 17 galleys were left when the fleet left for Venice. The "screaming / howling and lamenting / as one heard continuously / cannot be described / in that the women remained because of their dear spouses Wittiben / the mother of their sons / and the old people of their youth / as the only refuge of their antiquity." (P. 228). Vianoli follows on from the Giustiniani legend, including the now common comparison with the Roman Fabians. The family "which has its origins in the world-famous Kayser Justiniano" should not die out, therefore "forced her to marry Nicolaus, who was a Münch of around 18 years of age", namely "Annam, the daughter of Hertzog Vitalis" . While the couple fathered five sons and three daughters with their predecessors, Vianoli had eight sons (p. 227). With the “Armada”, “the plague also sneaked in”, which killed many thousands. Here, too, the Doge was accused of having "ought to have overcome the emperor with such a powerful force". Without mentioning the people's assembly, the author continues that the murder occurred on "Holy Easter Day 1172". The doge had gone to him “called la Rasse” because he “wanted to go to Vespers in S. Zachariæ churches”. He was there "with such a swift push (as was done by a daring villain) out of the middle / that even those who accompanied him / were not aware of it / while he was still biting the door of the churches / from them Clergy there led into the closter / in which several hours later he had ended the misery of his life / after 16 years of government / "(p. 228 f.). His successor endeavored to avenge the murder "which he also soon made to work / in that through his diligence the villain / who stabbed the heart / and someone named Marcus Casuol was / discovered and was hanged." P. 232). According to Vianoli, "in order to restrict the too great authority of the Hertzians", "their twelve were chosen from among the most distinguished / with the title of electoral masters, each of whom named forty others". This gave Vianoli 480 men, the "Raht of 480 men", who - with that Vianoli is alone - was supposedly elected for only one year. This procedure was repeated annually, so that “in such a way every inhabitant of the city would like to attain such honors / gain some hope” (p. 230).

For Jacob von Sandrart "Vitalis Michaël" in his Opus Kurtze and increased description of the origin / recording / territories / and government of the world-famous republic of Venice was "drawn to regiment" in 1156. He also counted him as the 37th Doge. Although he was happy in the fight against "the Emperor Friederich Barbarossa", he was "even more unhappy against the Greek Emperor Emanuel". Although he made peace with the Pisans, he also destroyed Trau “gantz; Ragusa plundered / and the island of Chios, now Scio, subjugated the Venetians; so the emperor turned himself / although he stopped all ships and goods to the Venetian merchants / that he did not want war / but peace ”. He held off the Venetians for so long "that the plague / it was now by accident / or through some trickery brought about by the Greeks", the whole fleet "went to shame". In Venice he was "killed as a traitor by the troubled people". “But afterwards the people began to repent of this / and it was only recognized / that he, as a loyal lover of the fatherland and the merchants, creates peace righteously / although unhappily sought / for which he could not be to blame; because of this, ten people are chosen / in order to punish them / who had committed this murder ”. However, the author also considers the possibility that the bonds “although with a promise / the republic should pay for such again and make good / as soon as it would be in a better position” “were part of the“ cause of the hatred against him / and may have promoted his death ”.

After-effects of the Venetian historiographical tradition, modern historiography

Johann Friedrich LeBret published his four-volume State History of the Republic of Venice from 1769 to 1777 , in which he stated in the first volume, published in 1769, that the Doge's successor had the murderer of his predecessor executed, but “nothing worried him more than the burden of debt into which the State overthrown by the previous prince. ”“ The treasury had to pay large sums of money, and the income was low. ”Accordingly,“ all capital was filled with sequesters, the administration of the funds was handed over to a procurator of the Heil. Markus, and satisfied the creditors with the assurance that as soon as the state had recovered somewhat, their demands should be satisfied. ”LeBret describes this as“ the first state banquerot of the Venetians ”(p. 362). "So far she had humiliated Immanuel". In complete contrast to this gloomy result of his reign, Vitale Michiel succeeded in almost everything at the beginning of his reign, as LeBret sums up: “Vital Michieli, the second, was a regent who deliberately weighed all dangers ... who she with a special presence of the spirit turned away, went boldly against the enemy, waged the most important wars, and bravely defied the emperors of the Greeks and the Germans ”(p. 321). He tried to pacify “the bitter enemies of his state” right from the start, “because he saw beforehand that he would have to argue with much more important enemies.” The agreement with Pisa was made because Frederick I was on October 22nd 1154 came to Lombardy. At the same time, "it seems that they [the Venetians] did not dislike seeing that the proud city of Mayland would be humiliated a little, even though they had not wished for its complete overthrow." The emperor reappeared in Italy on June 6, 1158 The siege of Milan began on August 8th, followed by its surrender on September 8th. But that was not the end of the fight. In 1162 Milan was destroyed, the Pope fled to France, which, like England, stood for Alexander III. had declared; When Venice took his side, Frederick canceled all contracts and regarded Venice as an enemy of the empire. "And if we believe the Dandulus faith, the governors of Verona, Ferrara and Padua attacked the Castell Capo d'Argine hostile." Since Adria had also participated in "grazing" around Loreto, the Venetians not only drove out the troops of the Lieutenants, but also burned the Adriatic area. The Doge sought negotiations with the northern Italian cities, which "opposed the German despot" and "defended the freedom of Italy". "Padua, Vicenza, Verona shook off the tyrannical yoke", Friedrich had to retreat to Pavia. In this context, LeBret also puts the attack of the patriarch "Ulrich von Aquileia". The Trevisans tried to hurry to the patriarch's aid, "But because they did not know the paths on these waters, they were attacked and cut down by the Venetians." "The patriarch with seven Friulian nobles" was imprisoned in Venice, the emperor moved north again over the Alps. At LeBret the prisoners had to promise to deliver a large ox and twelve large pigs and twelve loaves of bread every year in memory of this event (p. 324). Later, according to LeBret, the “smashing of the castelle by the doge” was abolished, in its day a “nice castell” remained from which fireworks were lit. In LeBret's time, pigs were also banned from Venice, so that only four oxen were beheaded; their meat went to the poor houses. In 1165 the Lombard League of Cities was established, which Venice now openly supported. England and Byzantium promised funds to rebuild Milan, Manuel even wrote to the Pope who had fled to Benevento . Friedrich's army, however, suffered from the "plague" after the train to Rome. Meanwhile, Manuel tried to reach a peace treaty with King Wilhelm of Sicily, which was supported by the marriage of his daughter Maria, but Wilhelm refused, which in turn made Manuel seek vengeance. Venice saw itself in danger if it refused the demand for support from Byzantium, to get between the two empires. But the peace with William, as well as the cooperation with Lombards and the Pope seemed to be more important to Venice. The Doge, who was well aware of the Byzantine "malicious and bloodthirsty intentions, found it necessary to seriously forbid all Venetians entry into the Greek territory." Indeed, Manuel made an association with Ancona. Archbishop Christian von Mainz demanded the delivery of the ambassadors there. Now the Doge made contact with the Germans he wanted to support, whereby his six Venetian galleys captured five Byzantine ones. The Doge had the two Venetians found there hanged. Nevertheless, Ancona resisted the siege. So this attempt to damage Venice had also failed. So Manuel tried it in Dalmatia. Maria, who had already been "offered" to Wilhelm, was now married to King Stephen of Hungary. Venice “ruled with great care” in Dalmatia. The local “citizens” were allowed to “choose their priors themselves”, and the three cities of Zara, Apsara and Arbe even elected Venetian nobles, ultimately two sons of Doge. These sons of the Doge married Hungarian women. Stephan now occupied cities on the coast, such as Sebenico, in Zara the Venetian count, son of the previous Doge, was driven out: "The archbishop of the city raised himself to the count and drew secular rule to himself". The Doge "went under sail with thirty ships", but had to abandon the operation "because of the Anconitan landing". Only then did a new fleet besieged the city, whereupon the Hungarians fled and the Venetians under Domenico Morosini took 200 hostages with them from "von der Nobler" (p. 329). Regarding Manuel, LeBret says: "Back then Europe had no more deceitful ruler than him." "Now he suddenly acted as if he were infinitely sorry that he got into such confusion with this republic". So he offered the Venetians to reopen his ports for them. The Doge did not want to decide this alone, "but called the whole assembly of the people together ... The tendency of the people determined the Doge to lift his ban." However, the two ambassadors Ziani and Malipiero were hardly in Constantinople when all the Venetians were arrested - what the emperor had denied before the ambassador. “March 12th of the year 1171 was the day on which the Greeks obeyed the orders of their emperor in the strictest possible way.” Despite this dramatic announcement, the author provides a differentiated picture of the process, because first of all those who were married to the respected houses in the state were to swear allegiance. When it came to looting and destruction, the emperor ordered reparations. Only when the Venetians threatened to do it again, as in the time of the emperor's father, did he arrest the Venetians throughout the empire. The Doge tried to prevent the news from getting around and there would be a tumult, but then 20 ships with refugees arrived, and "now the mob began to rage so that the whole city of Geschreye rang out." It 100 galleys and 20 transport ships were equipped. "During his absence, his son, Count Leonhard, was supposed to take over his father's position" (p. 331). In September the fleet sailed after 100 days of set-up time, the Istrians and Dalmatians joined them with 10 galleys. 30 galleys destroyed Trau, the rest "sailed against Scio". Ragusa had raised the imperial flag and was even pulling ships against the fleet. When a new storm was prepared, the city surrendered, had to swear an oath of allegiance, and the archbishop had to "submit" to the Patriarch of Grado. The governor of Negroponte made the doges believe that the emperor only wanted to punish the guilty, he would set the innocent free. So the Doge lost crucial time in negotiations. LeBret explicitly follows the description of the chronicler and doge Andrea Dandolo, who believed that Vitale Michiel had "exposed his fatherland to the greatest danger" by his simplicity. LeBret neither explains which guilty and innocent the emperor meant, nor whether the explicit mention of a negotiator who understood Greek might have meant something. Finally, the Doge moved to the newly conquered Chios to spend the winter, allegedly leaving the empire alone in anticipation of the return of its ambassadors. Manuel promised the ambassadors that he wanted to make a peace, but the negotiator he had sent received secret orders, according to LeBret, to postpone the negotiations. “The Greek envoy got to know all the strengths and weaknesses of the Doge.” Meanwhile his army “languished” “and was seized by the plague”. With regard to the alleged poisoning of drinking water, LeBret only says: “A historian who wants to believe all mob myths, mixes himself with the mob. Rather, the episode shows that the plague pursues the Doge on all the islands, and that his army even brought it with them to Venice ”(p. 333). The doge "saw his brave fighters fall like mosquitos". Manuel let him express his regret, which, according to the author, mocked him. Finally, the Doge had to give in to the wishes of his remaining crews and drive home with 17 galleys. LeBret also describes the Giustiniani legend, according to which the monk and last of the clan, from San Nicolo di Lido, married his daughter Anna, who gave birth to eight sons. “The people are finally shouting for a victim of this general consternation”, the Doge was accused of “negligence”, “shouting at him as the traitor of the fatherland”: According to LeBret, “nothing is easier than fermenting the mob in Venice "They entered the palace with an armed hand", the author varies the sequence, the doge fled "out of the palace through the back door" towards San Zaccaria. But "here, too, the mad rabble pursued him, and one of the cheekiest stuck a dagger in his body." He finally died in the arms of a priest who came to meet him from San Zaccaria, which he had still tried to reach. “As soon as he was different, then the heated nation went in again,” believes LeBret. And: "All righteous citizens abhorred the violation of public majesty". They regretted not being able to protect the prince from the mob. Overall, according to the author, this was the point in time when the attempt was increasingly made to set limits to the “arbitrariness and passion of either the prince or the mob”. “The whole constitution has been changed; the cheek of the people was dampened; the arbitrary power of the princes restricted, and the supreme authority communicated to a numerous assembly of nobles, which were again to be fenced in by fixed laws and led to a definite goal ”.

The fact that LeBret was barely received for a long time becomes evident decades later in the subsequent historiography. In his Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia from 1861, Francesco Zanotto also believes that the people are always 'gullible because ignorant' ('credulo perchè ignorante') and 'fickle as the sea', this manifests itself in “tumulti ed atti violenti”, in 'turmoil and acts of violence' (p. 103). Immediately after his election in February 1156, the Doge succeeded in balancing out with Pisa, but what he particularly emphasizes is Barbarossa's coronation in Monza with the “corona italica”, as well as the defense of Crema, which for the author is part of the most memorable and glorious in Italian history '. During the schism, Barbarossa called on the cities in question to take action against Venice, but the Paduans, Veronese, Ferrarese and Trevisans alike had to withdraw with heavy losses. Zanotto also reports on the Patriarch of Aquileia, from whom his counterpart Enrico Dandolo had to flee from Grado to Venice, of his defeat and capture. Finally, ox and pigs follow to Giovedi grasso . According to Zanotto after a detailed description, this festival, reformed under Andrea Gritti (1523–1538), existed until the end of the republic, i.e. until 1797. As soon as this undertaking was over, according to the author, Zara rebelled, which did not want to submit to the Patriarch of Grado, but was also driven by the Hungarian king. The Hungarians fled the dogal fleet of 30 galleys, "abbandonando tende e bagaglie", "giving up tents and luggage". The expelled Domenico Morosini was reinstated as Conte, 200 hostages accompanied the doge. Zanotto explains in detail the legal changes on Veglia, Arbe and Ossero, the islands of the Kvarner Bay , to explain that the King of Hungary could not get past this bulwark of Venetian power, but tried to gain influence through marriage projects. On the other hand, in view of the second conquest of Milan and the Pope's flight to France, Venice came under such imperial pressure that it could practically only trade via the Adriatic Sea, in fact, that Venetians could only leave their city by sea (“sicché ridotti erano, a non poter uscir che per mare ”, p. 100). According to Zanotto, this was the reason why Venice sought an alliance with both the Normans and Byzantium, and why Venice helped finance the Lega. Barbarossa, for his part, had crossed the Alps to assemble a new army. So the Pope returned, full of gratitude for the Venetians who had welcomed the churchmen who had been 'driven out by the schismatics'. All this had become so expensive for Venice that a loan of 1150 silver marks had to be issued, for which the income from the Rialto market was pledged for 11 years. The Lega conspired in Pontida on April 17, 1167, succeeded in driving the imperial Podestà out of Milan, then Lodi and Trezze fell . But Friedrich returned, punished Bergamo and Brescia, moved to Rome, where he was crowned again, while Alexander III. fled to Benevento. But the wrath of God hit the emperor in the form of an epidemic, his men demanded to return, so that the arson army withdrew north through Lombardy. In honor of the Pope, the Lombards founded the city of Alessandria . - In Venice there were outbreaks of the plague in 1157, 1161 and 1165, on December 15, 1168 there was a huge fire in the city, whereby the author refers to Sanudo . Only now does Zanotto come to Manuel I, who had tried to win Italy, where he encouraged Ancona to stand against Friedrich. Remembering the old friendship and privileges, he also sought the support of Venice in this project. When Venice refused, the emperor encouraged the Anconitans to pirate. Only then did Manuel 'openly show himself as an enemy', who reached for Trau, Ragusa and Spalato - 'e pose a ruba quelle infelici città' ('left these unfortunate cities to be robbed'). Now, for their part, the Venetians wanted war. The city was divided into " sestieri ", each sestier in "parrocchie", in church districts, each in turn was burdened with forced loans. Interest was 4% on these, payable in two annual installments administered by the Camera degli imprestidi , an institution that existed until the end of the Republic. Here Zanotto is moving these facilities forward a few years, the core of which only emerged after the disaster of 1171. The author reports conventionally on the construction of the fleet and very briefly on the progress of the operations. But he has to use the rhetorical trick that more than one chronicler reported that the Greeks had poisoned the water, which in turn triggered the "epidemia" to which 'the best' fell victim to without fame ("perivano ingloriosi" ). The Giustiniani legend is also not missing, this time the monk Nicolò Giustiniani and the Dog's daughter Anna Michiel had six sons and three daughters. The parents went, pious as they were, then both to monasteries, he returned, she went to San Girolamo, both were blessed . The epidemic forced the Doge to turn back after tumults, it was brought into the hometown. The doge tried to justify himself before the meeting, but he did not succeed in calming the tumult. He tried to flee to San Zaccaria, but was killed by some of the “più disperati” (“ucciso”).

Less educative and moralizing than LeBret, but given a more national tone, but more versed in source criticism than Zanotto, Samuele Romanin interpreted the poor and contradicting sources for this epoch. In doing so, however, he took uncritically much later information from manuscripts that he had viewed, in particular with regard to the internal constitution of Venice, at least occasionally used Byzantine chroniclers. In any case, he tried much more to classify the references to the Doge's life in the wider historical context, as he showed in the 19-page second of ten volumes of his Storia documentata di Venezia , published in 1854 . Italy in particular demanded the greatest attention at this time, “la massima attenzione”. It was not until 1158 that this tense expectation was resolved with Barbarossa's Italian campaign, 'four divisions', which the enemies of Milan joined. Friedrich forced a contract on the Milanese, but when they were no longer allowed to choose their own consules , a rebellion broke out. From Bologna there was another ban on Milan. With the election of Alexander III, a Guelf, Octavian IV, a Ghibelline antipope, was appointed. Venice sided with Alexander, like most other powers. After nine months of siege, Milan had to surrender on March 1, 1162, and the city was destroyed. Now Frederick has turned to Venice by inciting the neighboring cities, but also Aquileia. Pope Hadrian withdrew its patriarchy from obedience over the cities of Dalmatia in favor of the Patriarch of Grado, which was enough for Ulrich as a 'motive or pretext', as Romanin states (p. 76). Enrico Dandolo had to flee Grado, but Bernardo Corner near San Silvestro provided him with a site to build a palace. Now a Venetian fleet inflicted the said defeat on "Ulrico", the Patriarch of Aquileia. According to Romanin, the celebrations for Giovedi grasso were held annually until the time of Doge Andrea Gritti (1523) (p. 75). Since 1420, after all, Aquileia had already come to Venice this year, the "tesoro del Comune" had taken over the costs for this tribute, which no longer came in. In 1550, the slaughter of the pigs and the destruction of the wooden castles were stopped to make the festivities more 'worthy'. King Stephan of Hungary persuaded Zara to rebel, 30 galleys had besieged the city, and the Hungarians who had come to the rescue fled. All residents aged twelve and over now had to swear an oath of loyalty. The Doge, who returned home in triumph, proposed a “numerosissima deputazione di nobili” to determine the Conte of Zara. The latter chose the son of Doge Domenico, that Domenico Morosini (p. 76). In 1162 the Doge also decreed the “investitura” of the County of Veglia to Bartolomeo and Guido, the sons of the previous Count Doimo. To do this, however, they had to raise the sum of 300 “bisanti d'oro” every year to defend the island, they were no longer allowed to confiscate essential things such as boats or donkeys, and they had to maintain the legates from Venice. As a source for this, Romanin mentions in a footnote “Cod. DLI, ct. VII it. alla Marciana ”(p. 77, note 1). Arbe was allowed to choose four of its own candidates from among its citizens, or two Venetians, from which the Doge chose one. Nicolò, one of the Doge's sons, was nominated. Romanin considers the corresponding document to be important because it is sealed with lead. This shows that lead seals were in use even before Alexander III, who granted this right to Sebastiano Ziani . The island of Ossero fell to another son of the Doge, Leonardo. According to Romanin, the course of this process shows the still considerable influence of the “popolo”. Marriage contracts eventually led to the conclusion of peace with Hungary. - In northern Italy, however, Venice was cut off from trade. An alliance with Byzantium and Sicily was formed against the overwhelming power there. In return, Frederick distributed generous privileges to the allies in Genoa, Mantua and Ferrara. Alexander III, who fled to France in 1162, was brought back to Rome by King Wilhelm. The Pope thanked the Venetians for granting asylum to the cardinals and bishops who had fled the 'schismatics'. In view of all these expenses, a “prestito”, a loan, was issued for the first time in Venice in 1164. The rich Venetians affected were pledged the income from the Rialto market for eleven years. Sebastiano Ziani had 2 shares, as did Aurio Mastropiero. In addition to these two later doges, Annano Quirini, Cratone Dandolo, Tribuno Barozi, Pietro Memo, Giovanni Vaizo, Marco Grimani, Angelo di Ronaldo for a part ("parte"), Aurio Auro for half a "carato", an equally large share, how Leone Faletro and Pietro Acotanto upset him together. Again the author refers to the said Marciana Code (p. 79). In order to expand trade to Anatolia, contracts were signed with Turkish "principi". 'Without even taking up the word independence from the empire', so Romanin, numerous northern Italian cities joined in a promise of mutual help and the reconstruction of Milan. The city of Lodi, loyal to the emperor, had to surrender, the walls of Milan were rebuilt, and the treasure in Trezze was looted. Now Friedrich moved to Rome, Alexander fled to Benevento. But then an epidemic raged - it cost thousands of lives - in the imperial army, which had to withdraw amid great devastation "in Germania" (p. 81). The cities of the league, which was now called "Concordia", united in 1167 under a common oath of mutual aid, at the same time the ambassadors swore not to conclude a separate peace. The Venetians vowed to support the league with their fleet. Emperor Manuel tried to gain a foothold in Italy, but he was dependent on the Genoese and the Pisans for this, because Venice prevented corresponding attempts in Ancona. The Byzantine envoy in Venice, "Niceforo Calufo", had reminded the Venetians of the good relations and the "favori", but in Venice only "belle parole" were given, "nice words". The envoy then urged the Anconitans to pirate, but they were defeated by the Venetians, and their captains Jacopa da Molino and Guizzardino (or Guiscardo) were executed. When Byzantium occupied almost all of Dalmatia, Venice broke off trade contacts (p. 82 f.). Since the severe insults by the Venetian soldiers during the siege of Corfu, according to Romanin, Manuel has felt “a deep grudge” against Venice, “un profondo livore”. But the peoples of his empire had become so dependent on the Venetian traders that he tried to calm them down and to reconcile. The emperor had assured the negotiators Sebastiano Ziani and Aurio Malipiero that anyone who attacks a Venetian would be killed. Under various pretexts, however, the emperor had troops gathered in the capital in order to have all Venetians arrested at a favorable moment, on March 12, 1171, and to have their property and goods confiscated. In Venice there was great bewilderment (“sbigottimento”) (p. 83). Everyone was shouting 'war, war'. Everything necessary was given for a “giusta vendetta”, for a “just vengeance”. Then Romanin lists the first measures, such as the division of the city into “sestieri” and “parrocchie”, which were used for compulsory loans (“prestito forzato”) (which, however, only appear from 1207). He also brings these new measures and structures with these events to the other provisions, such as the annual return of "4 per cento", the payment of which began in March and September, and finally to the establishment of the "Camera degl'imprestidi" Context. Romanin referred to the "Vecchia Cronaca e Zancaruola", Gallicciolli and the "Cron. Magno. Cod. DXIII cl. VII it. ”(P. 84 f.). According to the author, it was the first “Banco nazionale” in Europe, which also issued “Obbligazioni di Stato”. The author also attributes the reluctance to the Doge, which ultimately led to his murder, to these burdens on the traders (p. 86). Finally, Romanin describes the departure of the “potentissima flotta” under the command of the Doge, while his son Leonardo stayed behind as a “vice-doge” (from p. 87). Although, according to Romanin, the doge should have known about the “slealtà”, the “faithlessness” of the emperor, he repeatedly entered into negotiations; this was a "gravissimo errore". Lack of discipline and the tightness of the ships caused the epidemic, and the emperor was also accused of having poisoned the wells. Even the air change (“per cambiare l'aria”) did not help. Here, too, nobody came back from the Giustiniani family of one hundred, and Nicolò was allowed to marry here too in order to father children (p. 89). The "plague" spread in Venice after his return, and the Doge called a meeting to justify himself. But he fled when he saw himself threatened, but was murdered on May 28 by the 'angriest', the 'più arrabbiati', near San Zaccaria.

In 1905 , Heinrich Kretschmayr argued more well-versed in source criticism in the first volume of his three-volume history of Venice . It makes it much clearer that at the latest with the treaty with William of Sicily 1154/55 Venice had marked out a kind of "sphere of interest" in the Adriatic, which began north of Ragusa (p. 240). Byzantine troops broke into these as early as 1151 when they were in Ancona. With the aforementioned treaty, Venice gave the Normans "the Greek coast south of Ragusa". Almost at the same time, Barbarossa confirmed to the Venetians their privileges in front of Galliate near Novara on December 22nd, 1154. In 1157 a delegation brought the emperor to the Diet of Besançon congratulations from the new Doge Vitale Michiel. And in 1156 they got along well with Pisa. Kretschmayr sums up: “Peace all around; that was the unexpected result of the Greek intrusion into Ancona ”. When Vitale Michiel took office, only the "reduction in trade tariffs from 10% to 4% for the Genoese in 1155", which the Pisans had enjoyed since 1111, was unpleasant. Even when Manuel sent troops to Ancona again in 1157, this did not disturb the peace. The question of subordination to the Patriarchate of Grado played an important role in the rule of the Adriatic. This increasingly became a patriarchate of Venice; so he called himself in 1177 in a document from Friedrich I of August 3, 1177 for the first time "patriarcha Venetus" (p. 243). From 1155 he was the primate of Dalmatia, in 1157 he received “the right to appoint and consecrate bishops in Constantinople and other Greek cities” (p. 244). While Arbe, Veglia and Ossero were still subordinate to the Archdiocese of Spalato in 1139, they were already in the obedience of Grado in 1154. The Pope subordinated them to the Archdiocese of Zara, which in turn was subordinate to Grado in 1155. The dispute over Istria between Grado and Aquileia did not end until 1180, so that Grado only remained the Zealand and the primacy of Dalmatia. Kretschmayr continues: "Venice experienced its investiture controversy around the middle of the 12th century" (p. 246). The Patriarch Enrico Dandolo, for example, when he rejected the Doge's interference in the election of the Abbess of San Zaccaria, appeared as an opponent of Doge Polani, and even had to flee in 1148 when he opposed his policies that were friendly to Greece. It was only Domenico Morosini that did not interfere in the spiritual elections. The price for this was the removal of the clergy from political life. But even the doge was soon no longer a monarch, but the conversion of the office began "to a kind of supreme official position". According to the author, this was possible in the shadow of the peace of the 1150s. - The breach of this peace occurred through Barbarossa's claims to power against the northern Italian communes, which he demanded in Roncaglia in November 1158. Venice, still in good agreement with Frederick in 1157, heard rumors that Frederick wanted to incorporate Greece into his empire. In 1160, Crema was destroyed, and on August 24th, Pope Alexander III. the ban on Friedrich. However, in October 1161, imperial envoys were still in Venice. It was not until the spring of 1162 that Frederick also opened hostilities against Venice, where many clerics had fled, like Alexander to France. The aforementioned attacks and counter-attacks around Cavarzere took place, Venice was subjected to a trade ban, whereas Pisa and Genoa were privileged. Venice joined the alliance system to which all enemies of the Staufer belonged, including Emperor Manuel, who "like the Staufer stuck to his imperialist plans" (p. 250). Manuel sent Nikephoros Kaluphes to Venice as envoy, he won Dalmatia and Croatia from the Hungarians. “In 1166, Nikephoros Kaluphes resided as a Byzantine dux of Dalmatia, presumably in Spalato.” In April 1164 a still secret alliance with Padua, Vicenza and Verona was established. Friedrich himself attacked from Pavia, Eberhard von Salzburg von Treviso and Patriarch Ulrich von Aquileja attacked Grado. The latter fell into the hands of the Venetians with "allegedly their 700". The Trevisans had not fared much better, the emperor was only able to achieve little success. The patriarch was released, but only twelve loaves and twelve pigs are occupied for 1222, and finally after 1312 also the aforementioned ox. A “folk festival that was initially somewhat massive, but from 1520 onwards was more dignified” reminded of this until 1797. Despite the sometimes open disputes among the extensive allies against the emperor, it was not until April 1167 that the Lombard League was founded. Barbarossa had to break off his campaign because of an epidemic. Venice was freed from military aid from 1168 onwards and was only supposed to fight the emperor on the sea and rivers, while the Byzantine and Sicilian subsidies passed through his hands. At the end of 1172 all of Northern Italy was in league against the Hohenstaufen. But now the conflict with Byzantium has come to a head. Manuel promised the Pope that the two churches would be united if he received the crowns of the West and the East, but the Pope replied ironically that he would have to move his residence to Rome. When he again brought troops to Ancona, Venice refused naval aid for Manuel in December 1167. Hungary, meanwhile connected by marriage contracts, attacked the Byzantine central and southern Dalmatia as early as the winter of 1167 to 1168. Manuel, for his part, urged the Anconitans to pirate again, and he favored Venice's trading rival from Genoa, which had also had a trading quarter on the Golden Horn since 1155. The Venetians and Pisans had devastated it together, but now, in October 1169, Manuel approved its refurbishment. They were also allowed to act in all cities of the empire. With the Pisans, whose quarters had been moved outside the city in 1162, he came to a friendly comparison in 1171. The Venetians were charged with a new attack on the Genoese quarter - Venice's merchants "met him in his own capital with violent arrogance and brazen impudence". In 1170 and 1171 he even negotiated with Christian von Mainz , or even sent envoys to Cologne. He was militarily successful against the Hungarians, as was Venice, with which the Hungarian king had fallen out because he had accepted Zara's voluntary subordination to his rule. Finally the mass arrest of March 12th, 1171. At first the rumors met with disbelief, but "allegedly on May 20th" appeared "some ships escaped from Halmyros". "Over the diplomatizing doge and the council, war was demanded and decided in a tumultuous popular assembly" (p. 256). The said fleet - "Venetian tradition is rightly proud of this powerhouse of domestic shipbuilding" - was launched and "Lionardo Michiele, the Comes of Ossero, was entrusted with the deputy government as vice duke." Then followed Trau and Ragusa - without Kretschmayr the imperial tower -, then "Euboea". The fleet overwintered on Chios, "set fire to the surrounding area from here." Furthermore, the repeatedly described unsuccessful negotiations followed, finally a "plague-like epidemic" broke out on Chios, "the Venetian tradition raises the monstrous accusation against Manuel that he had this brought about by poisoning the wells ”(p. 256), Kretschmayr distances himself more than earlier historiographers. At the end of March the fleet had to turn back after heavy losses. First she drove to “S. Panachia, northwest of Skyros ”, to which the ambassadors returned again without having achieved anything. While ambassadors were leaving again, the fleet sailed to Lemnos, then to Lesbos, and finally a storm drove them to Skyros, where "the saddest Easter" was celebrated on April 16. After Kretschmayr, there were perhaps 25 to 30 ships left when the return began. The author mentions the Giustiniani legend, which played a significant role throughout Venetian historiography, in just one sentence. “In an excited popular assembly, wild curses were loud against him [the Doge]. Threatened in life and limb, abandoned by his councilors, who carefully searched the distance, he fled in a boat against S. Zaccaria. He was stabbed to death in front of the church by a Marco Casolo. It was on 27/28. May 1172. He also found his resting place in S. Zaccaria. The murderer was arrested and hanged ”(p. 257). Kretschmayr doubts that the Doge “showed that statesmanlike and military incapacity”, “of which Dandolo accuses him”. According to reliable sources, he was considered to be clever and skillful, and he was "hampered by consideration for the compatriots held in the Greek dungeons" and so he asks just as rhetorically: "had not a mishap" that had overtaken Barbarossa nine years earlier, " ruined all his intentions? "