Domenico Morosini (Doge)

Domenico Morosini († February 1156 in Venice ) ruled Venice from 1148 to 1156. According to the historiographical tradition, as the state-controlled historiography of Venice is called, he was the 37th Doge .

Right at the beginning of his rule the allied Venetian- Byzantine fleet defeated the Normans of southern Italy. With King Wilhelm I of Sicily , with whose Norman empire they had been at war for a long time, a peace agreement was reached that secured the rule of Venice in the upper Adriatic, even if there was resistance in Istria . Venice's influence in the Adriatic now extended unhindered to the Marches and Dalmatia , where however a conflict with Hungary arose . There the Venetian Church of Dalmatia was placed under the Patriarchs of Grado . A treaty with the Roman-German King Friedrich Barbarossa recognized Venice's traditional trade privileges, which stabilized the intermediary position as a trade hub between the eastern Mediterranean and the Latin west.

The Doge's power within the Republic of Venice was restricted by a new oath, and influential advisers were added to him. In addition, the inheritance of the Doge's office, which had long been forbidden, was finally stopped. The alliance with Byzantium, in the opinion of some of the leaders an alliance with schismatics , led to violent internal conflicts. The Pope imposed the interdict on Venice. In 1150, a marriage project succeeded in balancing the conflicting families.

Family, origin, advancement

The Morosini have been recorded in Venice since the 10th century, so they belong to the case vecchie , the 'old houses'. In addition to several generals and fleet leaders, two cardinals , a patriarch and a total of four doges emerged from the family : According to Domenico, these were the doges Marino Morosini (1249–1253) and Michele Morosini , who died of the plague just four months after his election in 1382 died, as well as for his military merits with the honorary title Il Peloponnesiacus excellent Francesco Morosini (1688-1694).

Little is known about the time before Domenico's election. In 1124 he stayed in Tire , in 1147 he traveled with another ambassador to Constantinople .

As the son of Pietro or, as others claim, Francesco Morosini, Domenico belonged to a branch (ramo) of the Morosini family, which had a blue ribbon on a gold-colored background in the coat of arms . His date of birth is not known. Nothing is known about the family of his wife Sofia, who was buried in the same grave. Her name only appears in an inscription on this shared grave, otherwise nothing is known about her. Their son Domenico was later sent to Zara as a ship's captain, namely from 1170 to 1171 . In 1172 he appears among the eleven voters of Doge Sebastiano Ziani , thus his father's successor in the highest office. In addition to Domenico and Marino, the Doge probably had three other sons named Giovanni, Marco and Roberto (maybe another Morosino, but in this case it is probably a mix-up with Domenico). Sofia and Domenico also had a daughter who was her second marriage to the Doge Pietro Polani .

Domenico Morosini appears in the sources for the first time in 1124, as the inscription on his grave indicates, namely as "primus expugnator" of the city of Tire . The conquest of this city came at the end of a naval enterprise that the Doge Domenico Michiel had led to the Holy Land . This fleet, launched from Jerusalem at the request of Baldwin II , set out from Venice on August 8, 1122. Because Byzantium had refused to renew the comprehensive trading privilege of 1082 in 1119, the fleet attacked the Byzantine Corfu en route , but had to break off the siege of the main town without having achieved anything and in the spring of 1123 continue to the Levant, where it arrived at the end of May. After several victories, the siege of Tire began on February 15, 1124, and surrendered on July 7. On the way back, Byzantine Rhodes was sacked. From the base on Chios the Venetians attacked Samos , Lesbos and Andros . In August 1126, Emperor John II Comnenus was forced to recognize Venice's privileges.

In September 1147 Domenico Morosini stayed as envoy of Doge Pietro Polani , together with Andrea Zeno, in Constantinople. The two men were supposed to negotiate the conditions for a military alliance against the Normans of southern Italy, who had used the passage of the Second Crusade to their advantage and captured Corfu in a surprise attack. The emperor Manuel I Komnenus , who had ruled since 1143 as the successor to John II , had sent envoys to Venice who asked for help there. In October 1147, the two Venetians concluded a treaty with the emperor that provided for exemption from taxes on Crete and Cyprus (through a chrysobull, through which the Latin version has been handed down) in exchange for naval aid. In March 1148, the emperor also allowed an expansion of the Venetian merchants' quarters in the capital. The Venetian fleet was laid up in the winter of 1147 on 1148 and was to leave under the leadership of Doge Polani. But he fell ill in Caorle , so that he had to leave the command to his brother Giovanni and his son Naimerio. Returning to Venice, the Doge died while the fleet was still under way.

Doge's Office

Domenico Morosini was then elected Doge, but immediately had to devote himself to the fight against the Normans. Although his predecessor had personally taken command of the fleet in the spring of 1148, he fell seriously ill. The command was then given to Domenico and Naimerio Polani, brother and son of the Doge. The Doge died during the ongoing naval expedition between February and July 1148. The resistance against the Venetians lasted on Corfu until the summer of 1149, when the Norman garrison surrendered. The allied Venetian-Byzantine fleet also won a sea battle against the Normans off Cape Malea , which King Roger II had sent to devastate the Greek coasts. Only in a peace treaty between the Republic and William I of Sicily , the successor to Roger, who died at the end of February 1154, was Venice's supremacy secured in the Adriatic Sea north of Ragusa .

Towards the end of the war, however, the Istrian town of Pola rebelled along with other towns on the peninsula. Morosini sent a fleet of 50 ships under the command of his son Domenico and Marco Gradenigo. They forced the dissolution of the local league of cities, so that in the same year 1150 Pola, Parenzo , Rovigno , Cittanova and Umago were forced to take an oath of loyalty. On April 2nd, their representatives signed a contract sworn by 17 people, which the Bishop of Pola then signed .

Domestically, Domenico Morosini managed to defuse the tensions that had built up between the Polani, the Patriarch Enrico Dandolo and the Badoer under his predecessor Pietro Polani , and to calm the heated climate between the parties. The disputes were sparked by the question of whether Venice should help the Emperor of Byzantium. Enrico Dandolo, the Patriarch of Grado , and the Badoers had opposed supporting schismatics ( this schism had existed since 1054). The then Doge Polani had his opponents exiled and the houses of the Dandolo in the municipality of S. Luca demolished. This prompted Pope Eugene III. to impose the interdict against Venice . Domenico Morosini managed to equalize around 1150. In addition, a daughter of Raniero Polani, son of Doge Pietro Polani, was to marry Andrea Dandolo, nephew of the patriarch. The Patriarch Enrico Dandolo then returned with all the exiles, and the agreement was also approved by Pope Eugen.

In 1152 Venice intervened militarily against Ancona , because according to the Venetian view this city was guilty of piracy . Under another son of the Doge, Marino Morosini, a fleet drove towards Marken . In the same year a friendship agreement was signed, which allowed Ancona's traders to operate freely in Venice; Venice, for its part, wanted to treat all citizens of that city as if they were residents of 'one of the best parishes in Venice'.

For control of Dalmatia intensify the doge had his son Domenico for Conte (Count) of Zara rise. But Spalato , Traù and Sebenico submitted to the King of Hungary. To prevent the cities from being subordinated to another archbishopric , Pope Anastasius IV gave the pallium to the bishop of Zara Lampredius (1141 or 1154–1178) in 1154 and raised the city to the seat of the Metropolitan of Dalmatia. In 1157 Pope Hadrian IV confirmed this and also stated that all of Dalmatia should belong to the obedience of the Patriarch of Grado .

Furthermore, the Doge signed a treaty with one of the Crusader states, the Prince of Antioch , which provided for trade facilitation. In December 1154, King Friedrich Barbarossa also recognized Venice's privileges vis-à-vis the negotiators of Venice - the son of the Doges Domenico, Vitale Faliero and Giovanni Bonaldo.

Apparently the so-called Promissione ducale was introduced under Domenico Morosini , a sworn set of duties and power restrictions, which were later also recorded in writing, and which increased considerably in scope over the course of the following centuries. After the establishment of advisory Sapientes and the prohibition of heredity in 1143, this is considered a further step to restrict the power of the Doge and prevent the formation of a dynasty.

After large parts of the municipality of S. Maria Mater Domini fell victim to a city fire in 1149 , this district was rebuilt. The Church of S. Mattia was also built on Murano by the Corner family, and by the Gussoni the Church of S. Maria, later called "dei Crociferi". A hospital and an inn for poor women who had lost their husbands or son as the only breadwinner in the service of the republic were built on this. The bell tower of San Marco , begun in 912, was expanded to the current bell storey.

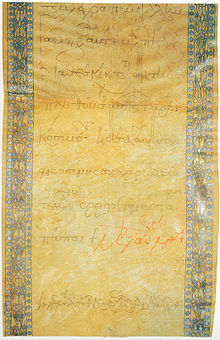

Domenico Morosini died in February 1156 and was buried in the Church of Santa Croce in Luprio , a church in the Santa Croce sestiere that no longer exists today. Like so many churches, this was repealed by a decree of Napoleon in 1810 and later destroyed. However, the text of the funerary inscription , which recalls the siege of Tire, the submission of Polas, the peace treaty between Dandolo and Polani and the one with the King of Sicily, then the discord by the Emperor of Byzantium, the renewal of privileges by Barbarossa has been preserved. A lead seal from the Doge recalls the Morosini as dux Venetiae, Dalmatiae et Croatiae .

reception

From the late Middle Ages

The Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo from the late 14th century, the oldest vernacular chronicle of Venice, depicts the events as well as the slightly older chronicle of Andrea Dandolo on a level that was long known at that time and largely dominated by the Doges - she even form the temporal framework for the entire chronicle. According to this chronicle, “Domenego Moresin” was brought to the doge chair by the “gentili et povollo de Venesia”. Right at the beginning of his reign, Roger II was defeated by Sicily. A fleet of six well-equipped and run galleys had hijacked a pirate fleet of ten galleys from Ancona, which was run by a "Guiscardo". This was executed without hesitation ("impicado sença alcun tardamento"). Under the command of “Moresin Moresin” and “Marin Gradenigo”, another fleet fought pirates and forced the cities there to recognize annual tributes in Dalmatia. When Roger died, "l'imperador Octon de Allemagna" - meaning Otto IV. - moved to "Lombardia et passò in Pulglia et de fino in Cecillia", so he moved from Lombardy to Apulia and Sicily, where he ruled everywhere pulled to himself. Now those of "Agolea et de Friul" attacked Venetian territory, as did "quelli de Lonbardia"; the former attacked Grado, the latter "Cavargere" ( Cavarzere ). The Doge personally led an army to defend Cavarzere, and the troops of the Patriarch of Aquileia and the Friulians were defeated with a large force. Finally, the author mentions a contract (“triegua”) “cum l'imperador Manuel de Gretia” and the death of the “imperador Octo de Alemagna”, whose successor “Ferigo Barbaroxa” will have “tancta disccordia cum la Ecclesia de Roma”. After eight years of reign, according to the chronicler, the doge fell ill, died and was buried in the "monesterio de Sancta Croxe honorevolmente".

Pietro Marcello said in 1502 in his work, later translated into Volgare under the title Vite de'prencipi di Vinegia , "Domenico Moresini Doge XXXVI." "Hebbe poi il Prencipato", he had the doge office without even mentioning how he came to this Office had come. However, he mentions the hijacking of (this time) five ships from Ancona that had robbed at sea. “Guiscardo”, your “Capitan”, “fu impiccato per la gola”. Immediately afterwards, Marcello claims that the construction of the bell tower of San Marco had started and then turned to "Marin Gradenico", the son of the Doge. This drove with “XL. navi ”,“ forty ships ”, against Pola and“ altri habitadori d'Istria ”, which had also been robbed. Then Pola was besieged and the city asked for peace. Around 2000 “libre d'olio” for St. Mark's Church was granted to them. Parenzo, on the other hand, now had to provide help with every war the Doge intended to wage. The “Nonesi” also had to deliver “certo tributo d'olio”, i.e. a certain oil tribute, and they also had to provide help. In addition, according to Marcello, the Anconitans had allied themselves with Venice, and peace had also been concluded with William of Sicily, who granted the Venetians active in his empire many "esentioni", ie exempted them from taxes. In addition, the "monistero della Madonna, dove stanno i Crocechieri" was attached by the Gussoni family. The Church of San Matteo Apostolo also became “edificata”. The Doge died in the eighth year of his reign, adds Marcello laconically.

According to the chronicle of Gian Giacomo Caroldo , which he completed in 1532, Domenico Morosini was "pubblicato Duce nel MCXLVIIJ". Caroldo also assumes that the bell tower of San Marco was built during his reign. He had already received the highest praise when Tire was conquered: “per haversi portato valorosamente, conseguì somma lode”. In October of his second year in power, a big fire began in the municipality of Santa Maria Mater Domini, with 13 municipalities burning down to "San Raphael". In order to settle the dispute with Enrico Dandolo, the Patriarch of Grado, a "figliuola di Messer Raynier Polani Conte d'Arbe in Messer Andrea Dandolo nepote del Patriarcha", a daughter of Renier Polani, Count of Arbe, and Andrea should be married Dandolo, Enrico's nephew. The damage to Dandolo's property was compensated for at the expense of the state treasury (“del dinaro publico reintegrati”). Pope Eugene III. I supported this because he wanted peace between Christians in order to be able to prepare the "espeditione contro Infideli", the fight against the 'unbelievers'. Because the inhabitants of Istria caused great difficulties ("inconvenienti") for the Venetian traders, 50 galleys were laid up to initially besiege Pola under the leadership of his son "Dominico Moresini" (here the author is wrong) and "Marin Gradenigo". At first, according to Caroldo, the city wanted to defend itself, but after an initial attack it asked for “perdono”. This was granted against the said oil tributes, as well as the cities "Parenzo, Città Nova et Rovigno", which had to swear allegiance. Thus the cities of the "obidienza" of Venice were subordinated, the fleet had returned glorious. The Doge's son was appointed "Conte di Zara" by the "Popoli Istriani". Together with "Vital Falier et Gioanni Bonaldo suoi Ambassatori" he was sent by his father as an envoy to Friedrich Barbarossa. With this they achieved the usual confirmation of their privileges and their usual "essentioni". With the Anconitans, the Venetians were “confederati et in amor uniti”, “allied and united in love”, so that there was no difference between them. An agreement was reached with Wilhelm that no more attacks were to take place north of Ragusa, while the Venetians in his empire received many "immunità". Finally, Caroldo mentions a few “constitutioni de Vadimonij e testimonij” which are very useful for the city and which the Doge issued with the greatest care. Caroldo also mentions “Chiesa et Hospital di Santa Maria”, which the “Gussona” family gave to the Congregation of the “Cruciferi”, along with “terreni et acque contigue”. Bonhaver Gussoni provided the house with a reasonable income. In 1155, Lunardo Cornaro handed over to God and the "Reverendo Henrico Patriarcha un fondo", ie land on which the residents ("circonvicini") built "San Mattio Apostolo". According to Caroldo, the doge died in February after seven years and seven months and was buried in Santa Croce.

The Frankfurt lawyer Heinrich Kellner , who saw the "sixth and thirtieth Hertzog" in the new Doge, mentions in his Chronica , published in 1574, the actual and short description of all those living in Venice , adding the year 1148 as the year of the elevation to office but in a marginal note: "* Petrus Justi: put 1147 but mine wrong." With him the five Anconitan pirate ships were "conquered and taken / also in captain Guiscard captured and hanged". The “wonderful and beautiful Werck deß Glockenthurns auff S. Marx Platz” was also started, “as it is”. At Kellner's 40 ships went to Pola "and the other Istrians or Schlavonians". Upon request, Pola received a promise of peace, but only in return for a tribute of "two thousand pounds / that is twenty cents of oil" for San Marco. The other provisions were those already mentioned by Caroldo. Kellner also mentions the "Bundt" of the Anconitans with Venice and the agreements with "Wilhelm / King of Sicily". “The monastery of our dear Frauwen / since the Creutzherrn are inside / the Gussoni (what a family in Venice) bawt the time. At the same time, the churches of Sanct Matthes were also built. ”According to Kellner, Morosini died“ in the eighth year of his duke's thump ”.

In the translation of Alessandro Maria Vianoli's Historia Veneta , which appeared in Nuremberg in 1686 under the title Der Venetianischen Herthaben Leben / Government, und Absterben / Von dem First Paulutio Anafesto an / bis on the now-ruling Marcum Antonium Justiniani , the author counts, deviating by Pietro Marcello, "Dominicus Morosinus, The 37th Hertzog". Although he was looking for peace, he occasionally took up arms in order to maintain it. “This clever state Maxim” caused the Doge to send out “several galleys” under the command of his son “Marco Morosini” against the said Anconitans. The captured "captain" of the "five galleys" "named Puiscard" had the latter "hang up / which made his Victori so much the more perfect and larger" (p. 216). The author saw “a public rebellion” in Istria; "After he [the son of a dog] had previously fought with Marin Gradenigo," they struck out with 50 galleys. The Istrians had scarcely been able to "become aware of the blinking of the Venetian sabers / when they had already let go of their arrogance again". The “rebel” Pola became a “humble supplicant”, and Parenzo also submitted. Here too, the “2000. Pfund Oels ", which should be used annually" for the divine service in S. Marxen churches ". The town fire that had started at S. Maria Mater Domini destroyed "what has been done there for more than a hundred years at great expense". - The "Sicilian King" "Rogier", who died, was followed by his son "Wilhelmus", with whom a peace agreement was reached, "who was of great benefit to the Venetians because of the action in Sicily". Vianoli also mentions the “Closter of Our Dear Women” and the “Church of the Holy Apostle Matthaei” as well as the bell tower of San Marco, which “has been completed”. "This Hertzog had the Principality seven bit into the eighth year". His successor was "raised to the throne ..." in 1156.

In 1687 Jacob von Sandrart in his Opus Kurtze and increased description of the origin / recording / territories / and government of the world-famous republic of Venice sufficed eleven lines to report on "Dominicus Maurocenus or Morosini", who ruled for eight years. In the second sentence of his statement he briefly mentions that the Doge “built the beautiful Thurn at the church of S. Marci”, that he “made the Histrians so apostate / brought them back to obedience”, “enabled the Anconitans to form an alliance” and entered into an alliance with "the Sicilian king Guilielmo". All in all, his government “turned out the merchants to a good advantage”.

After-effects of the Venetian historiographical tradition, modern historiography

Johann Friedrich LeBret published his four-volume State History of the Republic of Venice from 1769 to 1777 , in which he stated in the first volume published in 1769 that “the estates of the nation” had chosen “Dominicus Morosini”. At that time, the fleet was still in front of Corfu, as its predecessor had decided. Corfu was conquered, "the garrison saberbed down, and a pathetic bloodbath wrought." The island was handed over to Emperor Manuel, because "Venice was not yet bold enough to give this island to his rule." After the consultation in Valona, the fleet set up its attack Sicily, where, according to LeBret, “showed that one had learned cruelty in the wars of the Lord, and that killing and burning were glorious, if only it were done for the glory of the Lord.” When Roger returned, the allied fleets also returned home, where the Venetians supposedly only found out about the death of Doge Pietro Polani. Because Roger had kidnapped the Venetian silk weavers to Sicily, the Venetians saw "the war with Rogerius rather as a war of trade ... so that they could drive out all the products of the Orient alone". Emperor Manuel never saw the Venetians "as allies, but as his subjects"; the Venetians did not see him as a friend. But "Morosini had a pretty calm government". He only briefly mentions city fires and their counterweight, the construction of the aforementioned bell tower. He sent his son Dominicus Morosini and Marinus Gradenigo with 50 ships against the Istrian cities "which, contrary to the oath of allegiance, would have enjoyed swearing at the Venetian flag". The threatening appearance and the beginning of the siege prompted the residents to “ask for your forbearance and forgiveness”. They were "strictly forbidden not to let any more vessels put into the sea than when the defense of Venice required it". However, they had to deliver the said annual oil levy for the lighting of San Marco "as proof of their complete subservience to the Republic". The inhabitants of "Rubinum" came to meet the two naval leaders, they swore their oath of allegiance, wanted all Venetians in their city to be duty-free and promised to "pay five Roman pounds to build St. Mark's Church". Parenzo also submitted, promising 25 pounds of oil for the lighting of St. Mark's Church and 20 rams a year . In addition, they wanted to grant all Venetians freedom of trade and customs, "and if the prince allowed a fleet to leave, to send their ships to the heights of Zara and Ankona, and to contribute to the safety of the Gulf." Emona, also subject, should To deliver 40 pounds of oil, Umago two, “and all of Istria now seemed to be once again fortified in loyalty to Venice.” Ancona, hoping for help, allied itself with Venice. “Morosini never ceased to watch for the good of his fatherland. But nobody seemed to threaten it more than the crafty Emperor Immanuel ”(p. 319). King Wilhelm also applied "for the friendship of the Venetians". He did not promise any further alarm north of Ragusa, "only he would except those who had cargo on board for the benefit of the Greek emperor," and he reserved the right to take revenge on the Byzantine cities. "This was the first opportunity when the Venetians ... showed their secret resentment against Immanuel, although under the gloomy cover of secret negotiations." While Zara remained loyal, Hungary had "occupied Trau, Sebenigo and Spalatro and other places". Venice won the Pope, who "declared Hungarn unjust, and they were content with that." Zara declared that they would remain loyal to the capital; Dominicus Morosini gave her the honor of being their count until 1180. He obtained confirmation of the old treaties from Friedrich Barbarossa. As the author notes, from now on three ambassadors were sent to the court to find out the mood there, to wish the new king good luck and to extend the contracts. For other kings to whom this custom was extended, however, the number of ambassadors varied. Venice grew, “justice was administered with the greatest severity; the public revenues increased, the action flourished, and these advantages mark the reign of Morosini as happy years. ”He reigned seven years and seven months“ and died in the hornung of the year 1156 ”.

In his Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia from 1861, Francesco Zanotto believes that the new doge was 'called to the throne' by “consentimento generale della nazione”. This happened because he had made such great contributions in the conquest of Tire and in the fight against Roger of Sicily. In the land of this hostile king, according to the author, the Venetians wreaked havoc, they did not leave out any "eccesso" that humans are capable of. This victory was immortalized in the Sala dello Scrutinio in the Doge's Palace by the painter Marco Vecellio . After “Sanudo” a fire took place in 1149, which started from Santa Maria Mater Domini and destroyed 13 contrade. The fire reached as far as S. Angelo Raffaele in the west of Dorsoduro . Zanotto notes that Sanudo was often wrong, as he repeatedly assigned the same event to different epochs, as is the case in this case, where he also describes this city fire for the time of Ordelafo Faliero (meaning the city fire of 1106). - Zanotto dates the struggle with the cities of Istria in the third year of Morosini. In order to suppress their “fellonia” (“betrayal”) and to combat their piracy, the son of a dog “Domenico Morosini” led a fleet of 50 galleys (“galee”) together with Marin Gradenigo against Pola, who submitted and to the old treaties, but at a much heavier rate. Without mentioning the amount of oil that the cities now had to surrender for San Marco each year, the author mentions Rovigno, Parenzo, Cittanuova and Umago, which were further burdensome but which he does not name. The other troublemakers of 'free trade', the Anconitans, whose fleet commander “Guiscardo Brancafiamma” “venne impeso subitamente” suffered similarly, so he was immediately executed. Then Ancona asked for peace, so Zanotto, which the city was also granted. - Then there were new clashes between the Dandolo and Badoer on the one hand and the Polani on the other. Also with Zanotto, who explicitly follows Andrea Dandolo, the mentioned marriage project between an unnamed daughter of "Rainiero Polani", son of the late Doge, and Andrea Dandolo, "nipote" of Enrico, Patriarch of Grado, solved the dispute. Only now did Patriarch Enrico Dandolo return to Venice with his partisans. The successes of the son of the Dog earned him the office of "conte di Zara". But it was only a little time before the Hungarians recaptured Spalato, Trau and Sebenico and Venice was only Zara and the islands. At the request of Venice, the diocese of Zara was raised to an archbishopric by Pope Anastasius IV , to which all of Dalmatia should be subject; later it was subordinated to the Patriarch of Grado, who in turn later became the Patriarch of Venice. With William, the successor of Roger of Sicily, the Doge concluded a very advantageous contract for Venice's trade, "a condizioni utilissime al veneto commercio". The contract with the “principe” of Antioch was similarly advantageous, and it brought the Venetians their own warehouses and houses (“fondachi”) and their own court (“curia”) to judge their affairs. When Barbarossa came to Italy in 1154, the son of the Dog, along with Vitale Faliero and Giovanni Bonaldo, obtained the 'confirmation of the old treaties'. Inwardly, the Doge worked insofar as new laws were passed, such as on the testimony ("testimonianze") or the dowries , which were limited to "lire cinquanta di moneta veneziana". The bell tower should also be raised to the "cella campanaria". The doge, who died in 1155, was buried in a column arch in the church of S. Croce di Luprio, where Sanudo still found his epitaph . It was destroyed during the reconstruction of the church, but this could be done in the highly praiseworthy work of “cav. Cicogna ”. What is meant here is Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna . Among the new works with which the city adorned itself under the Doge was the Church of S. Maria dei Crociferi, next to which a house was built for poor women who had lost their husbands or only son to support their families. Zanotto contradicts the construction of the church of San Matteo at this time in a footnote. This church was neither built at that time nor by this family. In another footnote, he contradicts, also based on Cicognas Inscrizioni veneziane , the version of the name "Morosino Morosini" for the son of the Doge, who was also called "Domenico". His otherwise unknown wife Sofia only appears because she was buried in the same place as the doge (footnote 1, in which he makes fun of the absurd deductions of family relationships by the Venetian genealogists).

Samuele Romanin interpreted the sources in a less educational and moralizing way . In addition, he tried much more to classify the references to the Doge's life in the wider historical context, as he showed in the second of ten volumes of his Storia documentata di Venezia , published in 1854 . He claims that the new doge followed Polani's death 'hastily' (“prestamente”) in office. He also confirms that the Byzantines abandoned the Venetians, but also that they made fun of the emperor, mocked him and got into a scuffle with the Greeks, which made all the hatred obvious. They also destroyed the island of Corfu. Nevertheless, they attacked the returning Norman fleet together and captured 19 galleys. King Roger withdrew to his island, where he died a few days later. It was only with his son and successor Wilhelm that a peace was concluded that left the lower Adriatic to the Normans. Venice dealers should remain unmolested (p. 64). According to Romanin, the cities of Dalmatia had become pirate nests (“nido di corsari”) and no longer kept their treaties. The residents submitted to a fleet under the command of Domenico Morosini's son of a dog and Marino Gradenigo, after realizing that further resistance would be pointless. They had to agree not to burden the Venetian trade, to hunt the pirates, to provide ships and to keep oil ready for San Marco. The same was done with pirate ships from Ancona. According to Romanin, they were attacked and destroyed by a fleet under another of the Doge's son, Morosino Morosini. Domenico was raised to the "Conte di Zara". In 1154 the Pope made the Bishop of Zara a metropolitan over the cities of Dalmatia that did not belong to Hungary, and three years later over all the cities of the region (p. 65). In connection with Barbarossa's ambitions, the author describes in detail the special development that the Italian communes had taken, which intended to defend their “libertà” against the northern Alpine notions of domination, just as the papacy had changed in the investiture dispute. According to Romanin, Friedrich wanted to win two crowns in Italy, 'trim' the presumptuous cities ('abbassare'), 'put down' an 'ephemeral Roman republic' ('abbattere') and 'contain' the power of Sicily ('contenere') (P. 67 f.). On this occasion Frederick petted Genoa and granted the three ambassadors of Venice, namely Domenico Morosini, the said son of the Dog, and "Vital Faliero e Giovanni Bonaldo", the confirmation of the old treaties. The imperial coronation in Rome took place after the defeat of the republic and the death of Arnold of Brescia on June 18, 1155. Finally, Romanin briefly mentions the agreements with Antioch, as well as some "leggi civili", the "testimonianze" and "doti" concerned. In the collection of these laws, which now began, he cites Dandolo, whom he quotes, who would have thought that these would henceforth have been permanently stored in the statutes (p. 69, note 3).

Heinrich Kretschmayr argued differently in many ways in the first volume of his three-volume History of Venice in 1905 . Domenico Morosini reigned after him, perhaps from summer 1148 to February 1156. He only briefly mentions the move against the Istrian and Dalmatian cities, which is explicitly called "inclitus dominator totius Istriae". On April 2, 1153, the bishop and people of Pola swore the new treaty, which, according to Kretschmayr, "also had to swear to fifteen neighboring parishes". "Since the governments of Pietro Polani and Domenico Morosini, we no longer meet locals, but Venetians - often the sons of Dogs - as comites of the cities and islands mentioned". “Domenico Morosini, son of the Doge and conqueror of the pirates of Pola, is at least 1156 Comes of Zara. Only in Veglia did an evidently loyal native hereditary family assert itself in such a position. The traditional right of the indigenous population to choose the Comes remained untouched, but became an empty formality through the confirmation right of the Venetian government, through the granting of the Comes dignity for life and, moreover, through the pressure exerted by Venice ”. This “recognition of a Venetian sphere of interest” was confirmed by the contract with Wilhelm, who undertook not to “disturb the Adriatic from Ragusa upwards”. The author names the reason for the contract with Ancona that Emperor Manuel's troops stayed there until the winter of 1151. On June 26, 1152, Venice and Ancona signed “a kind of protection and defense treaty” (p. 240), which Romanin does not mention. After long negotiations, which Ugo von San Giovanni led in Palermo on the Norman side , a treaty was reached with Wilhelm . The Venetians received favorable trading conditions, which in turn surrendered the area south of Ragusa implicitly to the Normans, while north of Ragusa the Normans should no longer cause any concern. At the same time, on December 22, 1154, issued in front of Galliate near Novara, Frederick I confirmed the Imperial Pactum. In 1157, a Venetian delegation appeared at the Diet of Besançon to congratulate the emperor. In 1156 an amicable agreement was reached with Pisa . “The chronicler Martino de Canale of the 13th century therefore praises the Dogat Domenico Morosinis as a time of joy”. Even the privilege of the Genoese in Constantinople, for whom the trade tariffs were reduced from 10 to 4%, could not disturb the peace, and even when Manuel relocated troops to Ancona in 1157, the peace lasted. Kretschmayr believes that Venice needed this peace to consolidate internally. “In this way it was able to settle the internal conflict with its clergy, allow its constitutional development and reshuffle to proceed more calmly, guard its commercial advantages more carefully, pay particular attention to its Adriatic interests and strike a decisive blow against its Hungarian opponent in Dalmatia. The Venetian Church of Dalmatia was placed under the primacy of Grado ”(p. 241).

For John Julius Norwich , who in his History of Venice looked more at the constellation that came to a head in terms of foreign policy, the rule of Domenico Morosini, which lasted seven years and seven months, was more of a prelude to the subsequent disputes between the Pope, emperors and communes.

swell

Historiography

- Ester Pastorello (Ed.): Andrea Dandolo, Chronica per extensum descripta aa. 460-1280 dC (= Rerum Italicarum Scriptores XII, 1), Nicola Zanichelli, Bologna 1938, pp. 243-246. ( Digitized , p. 242 f.)

- Roberto Cessi , Fanny Bennato (eds.): Venetiarum historia vulgo Petro Iustiniano Iustiniani filio adiudicata , Venice 1964, pp. 111-114.

- Marino Sanudo : Le vite dei dogi , ed. By Giovanni Monticolo , (= Rerum Italicarum Scriptores XXII, 4), 2nd edition, Città di Castello 1900, pp. 228–256.

- Angela Caracciolo Aricò , Chiara Frison (eds.): Giorgio Dolfin. Cronicha della nobil cità de Venetia et dela sua provintia et destretto . Origini-1458 , Vol. I, Venice 2007, pp. 197-199.

- Roberto Pesce (Ed.): Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo. Origini – 1362 , Venice 2010, p. 62 f.

Documents, contracts, letters, seals, inscriptions

- Luigi Lanfranchi (Ed.): S. Giorgio Maggiore , Vol. II: Documenti 982-1159 , Venice 1968, n. 224, pp. 449-451.

- Antonio Stefano Minotto: Acta et diplomata e r. tabulario Veneto usque ad medium seculum XV summatim regesta , Vol. IV, Venice 1885, p. 10.

- Marco Pozza, Giorgio Ravegnani (eds.): I trattati con Bisanzio 992-1198 , Venice 1992, p. 59.

- Gino Luzzatto : I più antichi trattati tra Venezia e le città marchigiane (1141-1345) , in: Nuovo Archivio veneto, ns, XI (1906) 5–91, pp. 7, 49 f.

- Paul Fridolin Kehr (Ed.): Regesta pontificum romanorum , VII, 2: Venetiae et Histria , Berlin 1925, n.115, p. 62.

- Giovannina Majer: La bolla del doge Domenico Morosini 1148-1156 , in: Archivio Veneto , ser. 5, LXV (1959) 1-10.

- Agostino Pertusi : Quedam regalia insignia. Ricerche sulle insegne del potere regale a Venezia durante il Medioevo , in: Studi Veneziani VII (1965) 3–123, here: pp. 23–26.

- Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna : Delle Inscrizioni Veneziane , Vol. 1, Giuseppe Orlandelli, 1824, p. 240 f. ( Digitized version )

literature

- Giorgio Ravegnani: Morosini, Domenico , in: Dizionario biografico degli Italiani 77 (2012).

- Andrea Da Mosto : I Dogi di Venezia , Florence 1977, p. 62 f.

- Claudio Rendina: I Dogi. Storie e segreti , Rome 2007, pp. 116-120.

- Freddy Thiriet : La Romanie vénitienne au Moyen Age. Le développement et l'exploitation du domaine colonial vénitien (XIIe-XVe siècles) , Paris 1959, pp. 42, 45.

- Marco Pozza: I Badoer. Una famiglia veneziana dal X al XIII secolo , Abano Terme 1982, p. 43.

- Andrea Castagnetti: Il primo Comune , in: Giorgio Cracco , Gherardo Ortalli (eds.): Storia di Venezia , Vol. II, Rome 1995, pp. 88-90.

- Giorgio Zordan: L'ordinamento giuridico veneziano. Lezioni di storia del diritto veneziano con una nota bibliografica , Padua 1980, p. 191.

- Roberto Cessi : Storia della Repubblica di Venezia , Florence 1981, p. 156 f.

Remarks

- ↑ Irmgard Fees : The signatures of the Doges of Venice in the 12th and 13th centuries , in: Christian Lackner , Claudia Feller (ed.): Manu propria. From the personal writing of the mighty , Böhlau, 2016, pp. 149–169, here: p. 157.

- ^ Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna : Delle Inscrizioni Veneziane , Vol. 1, Giuseppe Orlandelli, 1824, pp. 240 f.

- ↑ Letter from Emperor Manuel Komnenus I to Pope Eugene III. Regarding the Crusade , Vatican Secret Archives, archive.org, August 22, 2013.

- ^ Roberto Pesce (Ed.): Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo. Origini - 1362 , Centro di Studi Medievali e Rinascimentali "Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna", Venice 2010, p. 62 f.

- ↑ Pietro Marcello : Vite de'prencipi di Vinegia in the translation of Lodovico Domenichi, Marcolini, 1558, p 69 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Șerban V. Marin (Ed.): Gian Giacomo Caroldo. Istorii Veneţiene , Vol. I: De la originile Cetăţii la moartea dogelui Giacopo Tiepolo (1249) , Arhivele Naţionale ale României, Bucharest 2008, pp. 137-139. ( online ).

- ↑ Heinrich Kellner : Chronica that is Warhaffte actual and short description, all life in Venice , Frankfurt 1574, p. 28v – 29r ( digitized, p. 28v ).

- ↑ Alessandro Maria Vianoli : Der Venetianischen Herthaben life / government, and dying / from the first Paulutio Anafesto to / bit on the now-ruling Marcum Antonium Justiniani , Nuremberg 1686, pp. 214-218 ( digitized ).

- ↑ Jacob von Sandrart : Kurtze and increased description of the origin / recording / areas / and government of the world famous Republick Venice , Nuremberg 1687, p. 34 ( digitized, p. 34 ).

- ↑ Johann Friedrich LeBret : State history of the Republic of Venice, from its origin to our times, in which the text of the abbot L'Augier is the basis, but its errors are corrected, the incidents are presented in a certain and from real sources, and after a Ordered the correct time order, at the same time adding new additions to the spirit of the Venetian laws and secular and ecclesiastical affairs, to the internal state constitution, its systematic changes and the development of the aristocratic government from one century to the next , 4 vols., Johann Friedrich Hartknoch , Riga and Leipzig 1769–1777, Vol. 1, Leipzig and Riga 1769, pp. 316–320 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Francesco Zanotto: Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia , Vol. 4, Venice 1861, pp. 94–97 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ He himself provides a sketch of the painting (Francesco Zanotto: Il Palazzo Ducale di Venezia illustrato da Francesco Zanotto, con incisioni , Venice 1841, plate CVXXI ( digitized )).

- ↑ Samuele Romanin : Storia documentata di Venezia , 10 vols., Pietro Naratovich, Venice 1853–1861 (2nd edition 1912–1921, reprint Venice 1972), vol. 2, Venice 1854, pp. 62–70 ( digitized, p. 62 ).

- ^ Heinrich Kretschmayr : History of Venice , 3 vol., Vol. 1, Gotha 1905, pp. 238–241 ( digitized , pages 48 to 186 are missing!).

- ^ John Julius Norwich : A History of Venice , Penguin, London 2003, 1st ed. 1982.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Pietro Polani |

Doge of Venice 1148–1156 |

Vitale Michiel II. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Morosini, Domenico |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Doge of Venice |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 11th century or 12th century |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 1156 |