Sebastiano Ziani

Sebastiano Ziani (Sebastianus) (* around 1102 ; † April 13, 1178 in Venice ) ruled the Republic of Venice from 1172 to 1178 . According to tradition , as the state-controlled historiography of Venice is called, he was the 39th Doge . At the same time he was the first doge who was not elected by the popular assembly. With him, the wealthy long-distance traders pushed through a kind of gathering in which the male heads of the most influential families gathered. Their access was limited to families who, in addition to wealth, were distinguished by prestige and traditional traditions. These upheavals were the direct consequence of the murder of his predecessor. This had lost a large part of the fleet and its men in the fight against Byzantium , and Venice had been badly hit by an epidemic brought in by the returnees.

This catastrophe required extensive interventions. On the one hand, Sebastiano Ziani laid the foundation for safeguarding and reorganizing state finances, for example through voluntary loans (imprestiti). These were in turn the basis for the later forced loans, with the help of which the wealthy were called in to the tasks of the community, above all the financing of warfare and the food supply. In addition, the municipality set up state supervision of a large number of trades, especially those that produce food. On the other hand, Ziani was ascribed a kind of early urban planning, whereby he mainly enlarged St. Mark's Square , provided it with new buildings and paved it, but also had the city divided into today's Sestieri , the six districts. For the first time, this allowed direct access to numerous resources of the city as well as profound state penetration.

Much more impressive, however, was his role as a mediator between the Ghibelline cities and Emperor Frederick I on the one hand and Pope Alexander III. , the Norman empire of southern Italy and the hostile municipalities of northern Italy on the other side in memory. Under Ziani's mediation, the Peace of Venice between Alexander and Friedrich came about in 1177. A number of legends soon grew up around this process, including an alleged one-year, secret stay of Pope Alexander in a monastery in the city and a fictional victory in a sea battle over a son of Emperor Frederick named 'Otto'.

Origin, up to the election of the doge

Sebastiano Ziani came from a family that was first recorded in a private document in 1079. The names Stefano and Pietro Ziani, sons of Marco Ziani, appear as witnesses in this document. Sebastiano Ziani, born around 1102, was one of the richest men in Venice. He owned extensive estates there, especially in the parish of Santa Giustina in the northeast of the city, where his family branch was located. There were also houses and shops between St. Mark's Square and Rialto , plus several salt pans in the Venice lagoon . The vineyard in the Castello sestiere , in which, according to legend, an angel appeared to the evangelist Mark , and where the church of San Francesco della Vigna was later built, also belonged to the Ziani family. In this way, Markus, the patron saint of Venice, earned the family the highest degree of prestige.

Sebastiano Ziani was actively involved in the profitable trade with the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa (see economic history of the Republic of Venice ). He invested substantial sums in the Levant trade during the 1140s and therefore made several trips to Constantinople , by far the largest city in the Mediterranean. There he appears as envoy in 1150 and 1170. From 1161 to 1166 he was iudex , which has often and not quite accurately been translated as "judge". He also worked as an advocator (Vogt) of the monastery Ss. Trinità e S. Michele Arcangelo in Brondolo . In doing so, he acquired a fortune that his son Pietro , who rose to become Doge in 1229, later increased.

Sebastiano Ziani appeared for the first time in a document as early as 1138, namely in one issued by Doge Pietro Polani . Under his immediate predecessor in the Doge's office, Vitale Michiel II , who was murdered at the end of May 1172 , Ziani held the position of iudex several times between 1156 and 1168 (a Doge advisor and thus one of the highest offices in Venice), then one of the Doge's sapientes, as well as 1150 and again 1170 held that of an envoy in Constantinople.

The Doge's Office

It was not until four months after the violent death of his predecessor Vitale Michiel II. Sebastiano Ziani was elected Doge on September 19, 1172. With his election, the right of the people's assembly (called arengo , concio , povolo ) to elect the Doge ended, or, as Andrea Dandolo notes, Vitale Michiel was followed by Sebastiano Ziani, who was the first Doge to come to office by election: “Sequitur de Sebastiano Çiano, qui primus per elecionem dux creatus fuit ”. Instead, the assembly of the burgeoning nobility, which later became the Grand Council, now appointed electors. The Doge election thus fell into the hands of a limited number of families, among whom a balance was created at the end of the reign by stipulating that only one member of each family could be elected to the group of these electors.

Ziani is said to have demonstrated his wealth by being the first doge to throw gold pieces among the people after the election. His term of office is considered important, both in terms of foreign and domestic policy. Ziani tried to prevent unrest among the population by limiting the prices for basic foodstuffs, but also by increasing price transparency (food law or calmiere ). The same purpose served a stronger supervision of the essential trades.

Already under Vitale Michiel II., Ziani's predecessor, the custom no longer to indicate the name of the Byzantine emperor on the silver coins, the denarii , but only that of the doge. With this, Venice finally shed any semblance of the emperor's supremacy. The devaluation of the currency in circulation, the silver denarius, was less of a symbol of power than of economic importance. From Sebastiano Ziani to Enrico Dandolo , Venice minted small, extremely thin and light denarii with a diameter between 5 and 11 mm and a thickness of about 0.5 mm, which weighed only about 0.41 g. The silver content was around 25%. The coins thus continued the devaluation of the denarius very strongly, but even more strongly under Enrico Dandolo.

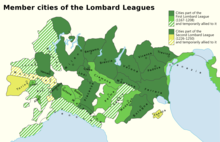

When he took office, the republic was on the one hand because of the clashes with Emperor Friedrich I , who had put the city under pressure with a trade ban in 1162, and because of the costs for the anti-imperial league of cities, the Lega Lombarda, on the other hand because of the clashes with the Byzantine emperor heavily in debt. In 1171, Emperor Manuel prohibited trade with Venice, which had enjoyed a far-reaching privilege there since 1082, with interruptions. The military counter-attack under the command of his predecessor had turned into a catastrophe. Constantinople, through which Venice had transacted a large part of its foreign trade, failed completely for several years.

In 1175 the Doge concluded trade treaties with the municipality of Pisa and with William II of Sicily , which brought him closer to former enemies, as his predecessor had done. In 1177 he renewed the traditional pactum with the Roman-German Empire and even signed a treaty with Genoa , with which there was a dispute for generations. With Byzantium, the most important trading partner until then, however, no compromise was achieved; several thousand of the local Venetians were arrested there in 1171 and later expelled.

His greatest success in foreign policy is shown to the visitors of the Doge's Palace on wall paintings in the hall of the Grand Council . After the defeat of Barbarossa, as he was called in Italy because of his red beard, against the Lombard League of Cities at the Battle of Legnano on May 29, 1176 and the failure of the imperial Italian policy, there was a meeting between Friedrich Barbarossa and Pope Alexander III. where the doge took on the role of mediator. In 1177 a peace treaty was signed in Venice and symbolically made visible to thousands. On the occasion of his visit to the city and to San Marco , the Pope issued an indulgence for every Christian who visited San Marco.

Ziani divided the more than one hundred islands of Venice into six districts, the sestieri . He found that the government buildings were too close to the shipyards and would be disturbed by the noise. Therefore, he bequeathed an extensive piece of land to the city and relocated the shipyards to where the arsenal was now being built . The renovation and expansion of the Doge's Palace , the demolition of the remains of the wall from the 9th century on the Piazzetta, as well as St. Mark's Square as a whole, was rebuilt, expanded and paved during his reign . Ziani bought several houses and a church and had them demolished. The main features of the square were given today. In addition, he had the two columns erected on the pier, which today carry the sculptures of the Lion of St. Mark and St. Theodore , the first patron of the city of Venice.

Sebastiano Ziani abdicated on April 12, 1178 and retired to the island monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore , where he died a day later. His tomb on the facade of the church was destroyed when the structure was demolished in the 17th century. His remains were transferred to a chapel in the new building. An inscription on a plate of white marble marks the day of this solemn act. His sons Pietro and Giacomo († 1192) received his considerable inheritance.

Five documents have been handed down from the Doge's term of office, three of which are original.

reception

From the late Middle Ages

The Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo from the late 14th century, the oldest vernacular chronicle of Venice, depicts the events as well as the chronicles of Doge Andrea Dandolo on a level that was long known at that time and largely dominated by the Doges - they form even the timeline for the entire chronicle. Therefore, right at the beginning of the comparatively extensive description of Ziani's rule , the Cronica indicates a drastic change in the electoral process, because from now on a new doge was never again directly elected by the “people”, the “povolo”. The author writes that “Sebastiano Ziani”, because “descension vene tra y citadini de Venesia per far duxe”, because “there was disagreement between the citizens of Venice” in the Doge election, came into office in a completely new way. This doge namely "per le caxe d'i gientili, ciò de Conseio, fu electo Duxe, cioè per XII de loro", thus elected by the 'houses of the nobles who sat on the council, that is, by twelve of them'. The 'council of wise men' or 'knowledgeable' ( consilium sapientium ) and the iudices , which made up the electoral body in which the most influential families were represented (who had a corresponding, far-reaching lineage), voted in a first step the new doge. This was then presented to the people in a second step, and only when the candidate accepted the candidate was it confirmed: “et poi, se'l plasese al povolo fusse confermado” (p. 66). According to the chronicle, Sebastiano Ziani was the first to be elected by the men in question and approved by the people. Andrea Dandolo described a little more precisely in his Chronica brevis what this "descension" was about. There it says that the new electoral procedure was introduced in order to avoid “pericula et scandala in creatione ducis”. - The author of the Chronicle describes a more extensive conflict, namely that between the emperor and the pope, as a “grave discordia”. Venice held it up with the church and supported Milan against Barbarossa, as did other Lombard cities that rebelled against the emperor “per comandamento de meser lo papa”, “on the orders of the Pope”. This “discordia” (“discord”) ruled for the time of three popes, up to “bon papa Alexandro terço”. However, he first had to flee to the King of France. But he couldn't stay there either. Soon he believed he could live “in Venesia oculto asay”, that is, “sufficiently hidden”, and so he had lived unrecognized for a year in the church and in the monastery “Sancta Maria dela Caritade”. But a stranger (“forastiero”) recognized him and reported this to the Doge and the Signoria (“lo Duxe et la Signoria”), whereupon the Pope was solemnly received (a scene similar to Dandolo). Under the leadership of the emperor's son "Octo", so the chronicle claims, a fleet of "galee LXXV" attacked Venice, which refused to surrender the Pope, but was turned into one by the "galee XXX" commanded by the Doge six hour battle defeated. The captured ships and the captured crews were brought to Venice. The Pope was surprised that the Venetians had defeated a three-fold superior force, as it is expressly stated. Otto had now reported to his imperial father about the "magnificentia et honor che facto gli era per lo dicto Duxe" so that he could declare himself ready to conclude a peace agreement. According to the chronicles, it was because his son had been treated so honorably that Barbarossa came to Venice to make peace. “Nella ecclesia de San Marco confermata fu la paxe tra questi tre grandi primcipi del mundo” (p. 68), with which the author placed Sebastiano Ziani on the same level of the highest “princes” as Pope Alexander and Emperor Friedrich. The “baroni”, immensely impressed by the city, accompanied “lo dicto Duxe et nobilli de Venesia” on a fleet of ten galleys to Ancona and even as far as Rome. Alexander III issued an indulgence for anyone who visited San Marco on certain days. But many "clerexi" (Cleric ') rebelled against the peace agreement and put themselves on the imperial side, so that the pope again excommunicated attacked. Ziani, on the other hand, emphasizes peace in Venice, because the Doge, according to the author, ruled “per tucto suo tempo in grande tranquillitade la cità di Venesia”. After seven years he died in the year "MCLXXVII" and was buried in San Giorgio Maggiore.

In 1502, in his work later translated into Volgare under the title Vite de'prencipi di Vinegia , Pietro Marcello meant the doge “Sebastiano Ziani Doge XXXVIII.” “Fu creato doge” with “maraviglioso consentimento de'nobili, & del popolo”. With this formulation he takes the character of a sharp turning point from the disempowerment of the people's assembly. With him, too, one of the three pillars intended for the piazzetta fell into the water, but the other two pillars on St. Mark's Square could be erected under the guidance of a Lombard. According to Marcello , the Rialto Bridge was built under Ziani . He first describes how “Arrigo Dandolo”, the later Doge and ambassador to Constantinople at the time, was forced by “Emanuel”, who had betrayed Venice in every way, “à guardar tanto in bacini affocati”, that he went blind (p . 77 f.). With the help of the "Ariminesi" it was possible to cut off Ancona in such a way that the city was "quasi besieged". Then the dispute between Pope and Emperor gave the Venetians "occasione d'honorata vittoria", but Marcello emphasized much more the military defeat of the imperial fleet and the numerous honors of the Doge. Barbarossa called a council after "Divione in Francia", but Alexander III. did not appear, so that the emperor marched “con grossissimo esercito” to Italy. But now his Pope "Ottaviano" died ( the author does not mention his papal name Viktor IV ), and the emperor installed "Guido da Parma" as his successor out of hatred against Alexander (whose papal name Paschalis III he also kept silent). Then he moved to Bologna and conquered Ancona (the Venetians played no role with Marcello), and then moved to Rome. Alexander fled on two of Wilhelm's galleys to Gaeta , then to Benevento , and finally to Apulia on the "monte Sant'Angelo" (p. 78 f.). “Su un bregantino” he finally fled to Zara and then - “travestito”, so 'disguised' - to get to Venice. He had gone to the “monistero della Carità”, but a certain “Commodo” recognized him and reported this to the Doge. 'As befits a Pope,' the Doge received the Pope with honor. He advertised with Friedrich by means of envoys - equipped with letters, sealed with wax seals, as 'it was custom' and lead seals , as they are used 'to this day'. But the 'angry' emperor demanded the extradition of Alexander. In addition, he considered the Venetians to be 'enemies of the Reich' (p. 80). Before long, the imperial banner would stand in front of San Marco. Venice was preparing for war. The emperor's son is with “LXXV. galee ”, claims Marcello too. Pope and clergy prayed for a victory for Venice, Alexander handed over to the Doge, who was currently “era per salir sù l'armata”, who was about to leave the fleet with “the gilded sword” - a scene that later painters to other places relocated. According to Marcello, the thirty ships of the Venetians defeated Otto's fleet off Istria not far from “Salboria” below Pirano . According to the author, 48 galleys were captured and two sunk. After Ziani's return with the imprisoned emperor's son, the Pope presented the victorious Doge with a ring and urged him, with his authority: “sposarete il mare”, the doge should “marry” the sea on a certain day every year, namely as Symbol of Venice's rule over the sea. With Marcello the emperor's son is released from captivity in order to move his father to peace. Friedrich received his son, who had almost been believed dead, with great joy. He asked him to end the war 'against which God and all saints' were (p. 82). Friedrich came to Venice with a “salvacondotto”, a letter of passage , and was received by Alexander, sitting on a golden chair. The emperor 'threw himself on the ground and kissed Alexander's feet', whereby in an extensive marginal note by another hand it is noted that Marcello is silent about the fact that the Pope put his foot on the neck, actually the neck (“gola”), des Emperor and quoted Solomon . 'It is said' that two umbrellas were brought for the Pope and Emperor, but that at the request of the Pope another was given to the Doge. In order to 'honor the Doge even more', the Pope gave him 'cereo bianco', 'white wax', i.e. a white candle. Upon his return from Rome, Alexander sent the Doge eight trumpets and golden standards to commemorate the victory. The Doge died 'very old' in the eighth year of his reign and was brought to San Giorgio. Marcello briefly mentions the decoration of St. Mark's Church and the expansion of the square where “grandi edificij” were created, “large buildings” (p. 84).

Marino Sanudo believes in his work De origine, situ et magistratibus urbis Venetae, ovvero La Citta di Venezia , which was never printed but circulated among the educated , that the Doge Ziani established the Institute of Procurators of San Marco as well (p. 104) as the Officium the Iustitia vetera (pp. 136, 266), the wheat chamber on Rialto (pp. 140, 271) or the butcher's supervision (141, 271). He was said to be the first among the “Dosi eletti”, namely “per li XI”, whereby the people were called to the St. Mark's Church (p. 85). The doge was buried in San Giorgio Maggiore, "A San Zorzi Mazor, l'arca di Sebastian Ziani doxe" (p. 51), one of the Sepolture di Dosi di Venetia , the burial places of the Doges (p. 236). Sanudo goes into more detail about the fact that a painting is being created in a hall of the Doge's Palace, which was to commemorate the battle against Barbarossa's son, the persecution of the Pope by the emperor, and Alexander's secret stay in Venice (p. 34): “Et continue rinovano ditta salla, sora telleri la historia di Alessandro 3 ° Pontefice romano, et di Federico Barbarossa Imperator che lo perseguitava, et, venuto in questa cittade incognito, fu conosciuto poi. ”To assist the Pope“ andò con l'armata contra il fiol Otto - chiamato di Federico preditto - et quello qui in Istria trovato con potente armata, et più assa 'della nostra, alla ponte de Salbua appresso Pirano lo ruppe, et frachassoe, et prese Ottone, et lo menoe a Venetia ". So here too the legendary victory and capture. After things had calmed down a bit, "Federico medemo venne a Venetia a dimandar perdono al Papa", Frederick came to Venice to ask the Pope for forgiveness, "et cussì ad uno tempo il Pontefice, et Imperatore erano a Venetia" - Pope and emperor were in Venice at the same time. On this occasion the Pope donated “certe dignità et cermionie al Principe et successori” (p. 34).

According to the chronicle of Gian Giacomo Caroldo , "Sebastiano Ziani" was elected the 40th Doge in the year "MCLXXII", ie 1172. Historians still disagreed on the counting of the Doges. Caroldo enumerates each of the Doge voters after he has explained the new electoral procedure, and never leaves out the predicate “Messer” reserved for the nobility: “Eletti furono Messer Vital Dandolo, Messer Vidal Falier, Messer Henrico Navigioso, Messer Lunardo Michiel , Messer Filippo Groto, Messer Renier Zane, Messer Aurio Mastropiero, Messer Domenego Moresini, Messer Manasse Badoer, Messer Rigo Polani, Messer Candian Sanudo. ”Sebastiano Ziani, 70 years old according to Caroldo, was“ dotato d'inestimabili ricchezze, intelligent et humanissimo ”, he was So endowed with 'inestimable riches' and wisdom and at the same time extremely educated (?). The new doge swore in front of the altar of San Marco to preserve the freedom of the 'churches', the (“chiese”) (plural!). Then he accepted the “investitura con lo stendardo in mano dal Primicerio della Chiesa di San Marco”, so it was invested by the Primicerius of St. Mark's Church. Only then did he become “intronizato” in the Doge's Palace 'according to custom' (p. 148 f.). As a first measure, he had the murderer of his predecessor executed without the author giving his name. Then he reconciled the quarreling and succeeded in 'calming down all differences and introducing peaceful life in the city' (“sedar tutte le differenze loro, introducendo il pacifico viver nella Città”). - Then the author reports on an embassy that had been sent to Constantinople by Ziani's predecessor, that is, of the envoys Enrico Dandolo and "Filippo Greco", as well as of a second in the form of "Vital Dandolo, Messer Manasse Badoaro et Messer Vitàl Faliero" who could also do nothing there. Thereupon Enrico Dandolo and Giovanni Badoaro were sent to King "Guielmo Re di Sicilia", "per far lega, da lui altre volte ricercata contra Emanuel Imperatore", in order to conclude an alliance against Emperor Manuel. As the author notes about the “commissione” of the imperial envoy, “Andrea Dandolo Duce scrive nella sua historia haver veduta et letta con la bolla di piombo”, Andrea Dandolo himself read the commission of the negotiators and saw the lead seal , but the Venetians received it just 'good words'. The ambassadors Vital Dandolo and Henrico Navigaioso also received nothing but “buone parole” from the emperor, “good words”. This demanded support against his enemies, which the negotiators in turn refused. When Sebastiano Ziani realized that this would not lead to a peace agreement, Aurio Mastropiero and “Messer Aurio Aurio” went to Sicily. Another embassy also returned from Constantinople with no results. Now Venice and William of Sicily concluded an alliance for 20 years, which could also be extended. After the experience in the Byzantine capital, where there was always only “dilatationi” (“postponements”), “fù statuito di non mandar piu 'Ambassatori a Constantinopoli et astenersi da queste prattiche”, so no further envoys to Constantinople and to stay away from these habits because there was always only consolation. - When “Federico Imperatore volgarmente chiamato Barbarossa”, “Emperor Friedrich, popularly known as Barbarossa”, had many cities subordinate to his sovereignty, Ancona , which did not have sufficient sea power , turned to Sebastiano Ziani for help. However, the Doge, who hated the Anconitans because they were attached to the Emperor of Byzantium, had the city blocked from the sea side, while Frederick's troops enclosed it from the land side. Because of the support of the "Contessa di Bertinoro et Guielmo di Marchesella di Ferrara", and finally, when the "intemperie dell'aria" prompted them, both the imperial army and the fleet of Venice gave up the siege. When the hostilities between Anconitans and Venetians increased again later, the Doge allied themselves with "Arimino" ( Rimini ) so that no one could dare to stay outside the city walls of Ancona (p. 151). After the author has interwoven that three valuable columns from Constantinople had been landed at San Marco, one of which had fallen into the water, he came up with a fundamental change in the supervision of the municipality. In order to “reprimere la malitia et fraude delli bottegni”, in order to counteract “the badness and deception of the shopkeepers”, “Giustitieri sopra li venditori di vino, biade, frutti, sopra li pistori, tavernieri, becchai, ternàri, gallatorinari, pescatori et simili, regolando simil cose con giustissimi decreti “, overseer of the sellers of wine, grain, fruit, the hawkers, tavern owners, butchers and other trades. From this “officio”, “while the city grew”, the “giustizieri novi et vecchi, officiali al frumento, al Datio del vino, Vicedomini della ternaria et officiali delli ternari et dopo ', li proveiditori delle biade” ins Called to life, i.e. supervisory authorities that deal with foods such as wheat, wine, olive oil , etc. (p. 152). - In unusual detail (pp. 152–154) Caroldo describes the meticulously planned external framework of the peace negotiations and the ritual treatment of 1177. Barbarossa first had an “ambasciatore” in Rome explain the reasons why the Venetians Alexander III. and did not recognize the antipope "Ottaviano" in order to then declare himself ready to conclude a peace agreement. "Dopò, detta Maestà fece molti segni d'amore verso il Duce Ziani", while Alexander of Apulia fled to Venice on ships of the Normans, which he "alli XXIIIJ di Marzo giunse". With Caroldo he went to the monastery of San Nicolò di Lido (p. 152). On “XXV di Marzo MCLXXVIJ” he was solemnly led into St. Mark's Church, accompanied by the Doge, the clergy and the people, between the Doge and the Patriarch Enrico Dandolo. Finally, in the presence of envoys from the French and English kings, as well as the Archbishop of Mainz, a peace agreement was reached. Now messengers (“nuncij”) were sent to the emperor to invite him “per firmar et stabilire ciò che era concluso”, i.e. to sign and confirm what had been decided. The Doge sent his son Pietro Ziani to Ravenna with six galleys, accompanied by “molti nobili et degni personaggi”, “many noble and worthy personalities”. Barbarossa came by galley to Chioggia , where many cardinals and prelates stood ready in his honor , sent by the Pope to accompany him to San Nicolò di Lido. Another son of a dog, Giacomo Ziani, was waiting for him there with many “nobili” who received “Sua Imperial Celsitudine” with the “segni d'honor et riverenza che siconveniva”. The following day the doge, the patriarch, bishops and clergy came to San Nicolò on numerous "pomposamente preparati" ships, as well as many nobles and citizens. On the Doge's richly decorated ship, the Emperor, the Doge on his right hand and the Patriarch, “con gran trionfo” on his left hand, was escorted to San Marco. In front of the gate, the Pope sat under a pulpit amid his cardinals and prelates. The emperor kissed the Pope's feet, whereupon he picked him up and kissed him on the mouth, which everyone could see (“che tutti viddero”). Then, to the right of the Pope the Emperor, to his left the Doge, the three men entered the church to the singing of Te Deum laudamus . At the altar everyone offered his prayers “con l'offerta, secondo il solito suo”. Then he was escorted to the Doge's Palace, where he was lodged with his courtiers. With the ensuing peace treaty, in which the emperor had promised a crusade , the situation in Italy was 'calmed down'. "Prelati, baroni, cittadini et populo" could not hold back their tears for joy ("letitia"), especially the Venetians, who thanked the divine goodness that their city would have considered worthy to receive the "due luminari maggiori" of Christianity , and to have made the Doge an appropriate tool for such a benefit for the "Christiana Religione". At the instigation of the Pope, so Caroldo, a twenty-year peace treaty was also concluded with William of Sicily, as well as other agreements in Italy. After Caroldo, Barbarossa stayed in Venice for two months, during which he “concluse stretissima amicitia et unione” with the Doge; then he returned to 'Germany' ("Alemagna"). The Pope celebrated masses in San Marco, "diede in dono al Duce la rosa", and promised indulgences to the visitors of the church, as well as to the visitors to the church of Santa Maria della Carità. He also drove with the “ Bucentoro ” to the wedding of the Doge with the sea (“a sposar il mare nel detto giorno della Ascensione”). The Pope finally returned to Apulia with four galleys that the Doge made available to him. - The seriously ill doge, advising his "propinqui et amici", instructed that certain rules should be observed when choosing his successor. So should four "primarij patricij", who stood for an "elettione sincera et lealmente", and swore it. His will left many houses to the Markuskirche; some say, Caroldo said, that he left them to the commune. He left the houses of San Giuliano, ie the "merzaria", to the monks of San Giorgio Maggiore, and the prisoners were given bread permanently. After Easter he was brought to the monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore, where the next day, the “XIIJ d'Aprile MCLXXVIIJ”, he 'passed into a better life'. Then Caroldo quotes the inscription on the tombstone in order to list the forty men who, elected by the said four, chose the new, 41st doge, "Aurio Mastropiero".

Knowledge of Venice's history was probably rather poor in the German-speaking area. Only a few writings about Venice circulated there, such as that of the pilgrim Arnold von Harff , who had visited the city at the end of the 15th century, and who also mixed up a number of traditional events. He reports on “Keyser Frederich”, whom the Pope had portrayed “with sijnem roden bard”. The Pope wanted to warn the Sultan that he was dealing with the Emperor if a pilgrim or messenger were to appear. When Barbarossa, recognized by the picture, was seized, the sultan triumphed: “wye hayt dich dijn broeder dijnes glouuen verraiden!” As a result of this betrayal, the emperor was imprisoned for a year and a day and had to pay a ransom of 200,000 ducats . The sultan gave him half of the money so that the emperor could fight his treacherous fellow believers. Friedrich had now moved to Rome, the Pope fled to a monastery in Venice in a monk's robe, where he was "the brother koch wairt", as the author emphasizes three times. With Arnold it was a pilgrim from Rome who recognized the Pope, whereupon the Venetians fetched the Pope in a procession and "with great reuerencie" from the monastery. The emperor had demanded the extradition of the Pope, otherwise, he swore, he would destroy Venice and turn the St. Mark's Church into a stable. He had moved to Venice with his “soene Otto”, but he wanted to bring more troops. Now the Venetians would have defeated Otto and taken him prisoner. Only if Friedrich threw himself at the Pope's feet, according to the Venetians, would they release Otto, for which the Pope's foot on his neck is expressly mentioned as a condition. This is how it happened, the author notes laconically: “the pays trad dem keyser off sijne scholder”, the emperor meant “non tibi, sed Petro, nyed dir dan sijnt Peter zo eren”. Later on, more legends were to grow around this skirmish. Sufficient atonement had thus been made, according to Arnold, but the emperor's oath remained. On this occasion, Arnold presented an original justification for the bronze quadriga on the outer facade of St. Mark's Church, because this reminded of Barbarossa's oath to make the church a stable. The four metal horses “zo ewycher gedechtenyss deser geschicht” were made around this “great swoirs wylle den he geswoeren hadde bij sijnem roden barde”. The author was probably not aware that it was looted property from Constantinople that the Venetians had brought with them after 1204. The pilgrim also names the painting in a hall of the Doge's Palace, which is reminiscent of Friedrich Barbarossa: "in deser raitz kameren steyt the legend of van deme keyser Frederich Barbarossa is e-mailed deliciously" (p. 45).

The Frankfurt lawyer Heinrich Kellner , who sees the 38th Doge in the new Doge “Sebastian Ziani”, thinks in his Chronica , published in 1574, that this is the actual and short description of everyone who lives in Venice , that he “struggled with the unanimous nobility and the common / Hertzog “. Kellner, who lived in Italy for some time and made Venetian historiography known in German-speaking countries, where his presentation is based on Marcellos, says: "At the beginning of his regiment, three very large stone columns were brought from Greece to Venice". However, while one column fell into the water during reloading, “the other two” “were judged by a master from Lombardi on S. Marx Platz. This Werckmeister was also the first to make the bridge on the Rialto ”. When Emperor Manuel heard that “the great death would come to Venice instead” after the fleet had had to leave, and after the death of his predecessor Zianis (moreover, according to Kellner, the Emperor Enrico Dandolo had forced Enrico Dandolo “that he was so long had to look into a fountain / bit he went blind ”), he dissuaded Ancona from the alliance with Venice. With him, too, the alliance with "Arimini" followed, so that Ancona was, as it were, "as much as besieged". When "Bapst Alexander the third / with Keyser Heinrichen the first of the name / was unpeaceful", the Venetians received an "opportunity" "to a great victory and Victorien." After the "separation or scisma" between Alexander III. and “Octaviano”, Barbarossa leaned towards the latter. Alexander did not appear before the “Concilium” in France, which “totally angered” the emperor. The emperor moved to Italy, but Octavian died, so that he now put "Guidonem of Parma in front of a successor", whose papal name the author also conceals, as does Marcello. Then he conquered Ancona and moved to Rome "to drive out Alexandrum". Waiter like Marcello describes Alexander's escape route, and he also adds that “he can't trust anyone” and Wilhelm “doesn't believe too much either”. So he fled further over "the mountain called S. Angelo / Monte S. Angelo" to Zara - "there he disguises himself" - "and thus came to Venice unknown". "He didn't want to trust the peace either / for a while kept secret and hidden in the monastery a la Carita / that is / to love / and did not acknowledge anyone." But someone with the "surname Commodus" had him recognized and communicated this to the Doge. Ziani promised the Pope after a due reception "that he should be atone with Keizer Friderichen / and receive his dignity / honor and merit / again." The author also names the "legend" according to which the Pope puts the wax seal on the envoy's letters I had lead replaced. However, the emperor had demanded the extradition of Alexander, had threatened Venice with war and he wanted to regard the Venetians as enemies of the empire. Otherwise they would "see in a nutshell deß Keyser's flags and arms on S. Marx Platz" (p. 31v.). In Venice one was now “worthy of the big raid every day” after having prepared a fleet, and soon the emperor's son Otto approached with “five and ten galleys”. Pope and "Clerisey gave the Armada the benediction and blessing". Then "the Bapst turns to the Hertzog Ziani / when he wants to go into the ship now / came with a golden sword / and other knightly defenses and symbols". When the imperial fleet found its thirty galleys "in the Istrian or Shlavian Sea", they chased the enemies to flight, "forty-eight galleys were taken / and two drowned". "Otto / deß Keyser's son / was captured" and brought to Venice. Kellner also describes the handing over of a ring to the Doge in order to solemnly celebrate the marriage to the sea, so that everyone can see "that by martial law we have the territory and rule over the sea" (p. 32r). Otto, who was released on the condition that his father be able to make peace with the Pope and Venice, was "accepted and received with great joy" by his father, especially since the father had "made a lot of worries about his life" . Otto has now stated that they are waging an “unjust war” and that God and all the saints are against them. The emperor, convinced by the words of his son, went "Peter Ziani / deß Hertzüge Sohn / with six galleys to meet Ravenna". In front of San Marco, Alexander awaited the emperor “sitting on a glazed chair,” Friedrich kissed the Pope's feet, who immediately picked him up and kissed him on the mouth. Then they went to the altar and now “Bath Keyser Friederich humbly the Bapst for forgiveness / and honors him as a right Bapst and governor of Christ”. “It is said” that “two heavens” had been brought to both of them, whereupon “the Bapst ordered / that one should be transferred to the Duke of Venice / he and his followers should use it forever. Also venerated in addition to the Bapst with a wise waxy card. ”After returning to Rome, Alexander had eight“ iron pipes ”and eight“ flags ”brought to the Doge in memory of that victory. The Venetians used these things "as they still do today". The old doge died and was in "S. Georg "buried; "In the same closter he puts a lot of goods and people in the Kauffmansgass". His gravestone can still be read - Kellner provides a rhyming translation into German - and with the date of death April 1178, or “OBIIT ANNO DOMINI MC LXXVIII. MENS. APRIL. “.

In his opus Venetia città nobilissima et singolare, Francesco Sansovino also counts Ziani as the 38th Doge, who took office in 1173 at the age of 70 (p. 230v). After him, too, Sebastiano Ziani was the first doge to be brought into office according to the new electoral mode (p. 179v), elected by 11 or 12 electors (p. 230v). He was the first, 'as they say', to throw money among the people (181v), a custom which, according to the author, was adopted by the Byzantine emperor (p. 230v). He had won, this time with “37th galee” “contra l'armata di Federigo Imperatore” (p. 178v), and also the inscription near Piran, on the church “S. Giovanni di Salboro ”, which recalls his victory over Frederick's fleet, he quotes in full to also mention“ Othone ”(p. 198, p. 231r), the emperor's son. At this point, Sansovino feels compelled to provide evidence of this naval battle, as its existence had already been denied outside of Venice (see below). Therefore he quotes Petrarch : "Apud Venecias victus pacem fecit"; the emperor thus made peace after he was defeated. After Sansovino, Pope Alexander III. the rule over the sea to Doge Sebastiano Ziani '(p. 122v, 199r – 199v), who had moved into Rome and received a number of gifts from the Pope (p. 183v). Sansovino quotes from the "Annali" of Andrea Dandolo, "come testimone di veduta, di haver letto le commessioni del Doge Ziani fatte l'anno 1173. ambasciadori mandati da lui a Emanuello Imp. Di Costantinopoli, segnate col piombo", so he has seen as an eyewitness the letters of the Doge, sealed with lead seals , for the ambassadors from 1173 to the emperor (p. 188v). Sansovino states that the church of San Geminiano was torn down by Ziani or his predecessor (p. 196v). Finally, the author names Ziani as the founder of the “Magistrati & Giudici” (p. 211r). In his will, the Doge not only noted the well-known properties on San Giorgio Maggiore and near St. Mark's Square, but also 'mills' (“molini”, p. 201r). After his death a "vacanza" was created until his successor was elected (p. 231v). - In his work Delle Cose Notabili Della Città Di Venetia, Libri II , he also mentions that the Doge's legacy was so extensive that a second procurator had to be appointed to administer it (p. 22). Sansovino also mentions the victory over Otto, whom he accordingly captured, and the Pope's ring as a symbol of rule over the sea. In this context he expressly quotes “ Sabellico ” in order to explicitly distance himself from the opinion that those who perished in the naval battle without sacrament would at least show respect (p. 27). Here, too, he repeats the story of the aforementioned victory over Otto and his imprisonment (p. 105), but does not mention the number of ships the emperor's son had at his disposal. Instead, he mentions the 30 “Navilij” which the Doge had occupied with “giente scelta”, ie with “selected people” (p. 106) - which meant victory over the numerically superior fleet or the small number of available ones Like to explain ships. Finally, he adds to the story of the Pope's long, unrecognized stay in Venice, of the discovery by “un certo Commodo di nation Francesoe”, who came through Venice as a pilgrim on the way to the Holy Land . At first he 'couldn't believe' that he had seen the Pope, whom he had already seen in Rome and who he believed was dead or in Constantinople. Then, without saying a word, he left the church and described the clothes and the “fisionomia” of the Pope to the Doge so that he could visit him and recognize him (p. 24 v – 25r). In fact, so the story goes, Commodo recognized the Pope and showed him to the Doge. He threw himself at the feet of the Pope after the service.

In the translation of Alessandro Maria Vianoli's Historia Veneta , which appeared in Nuremberg in 1686 under the title Der Venetianischen Herthaben Leben / Government, und Absterben / Von dem Erste Paulutio Anafesto an / bis on the now-ruling Marcum Antonium Justiniani , the author counts differently by Marcello, Kellner and Sansovino, "Sebastianus Ziani, The 39th Hertzog". This was "the first / who had started to use the common and differentiated coins among the people / so that he would like to receive the same shouts and shouts of joy all the sooner." He tried to kill his predecessor to avenge, “by the villain / who gave the horrific puller the sting through his diligence / and someone named Marcus Casuol was / discovered and was hanged” (earlier authors had not mentioned the name of the murderer Marco Casolo ). He also had the Doge's Palace "expanded / adorned with a lot of rare things / as well as the warm and beautiful church of H. Georgen / built as the other St. Jeremias called", where he had lived before the election. Vianoli also mentions the aforementioned columns, two of which were erected on St. Mark's Square and decorated with a representation of St. Mark and Theodore (p. 233). The responsible builder from Lombardy “also built the big bridge / which connects the Insul Rialto”, but he adds that the master and his descendants have been awarded an annual “pension”. Also, no one dared to erect the two pillars, which he achieved with eight people alone. - Frederick with the "surname Barbarossa" was now at war with Alexander III. A Roman named Octavianus had "raised himself as a Pope", Alexander fled to Venice, where he "had salvaged himself". "But after he recognized a burger with the name Commodus / and such was announced to the Raht as soon as it was announced / he was held and tractiret by the Hertzog and the entire Senate with due honors". So “a number of emissaries went to the Kayser”, but they were “dealt with” with threats of war if they did not extradite the Pope. "At that time the Imperial Armada consisted of 75 ships," but it was defeated by the 30 ships of the Venetians led by Ziani. If you follow Vianoli, 28 ships were captured and two sunk (at least 20 fewer than Kellner's). Here, too, “Otto des Kayser's son / who commands the Armada / himself was caught” (p. 236). After this victory the Pope pulled a ring from his finger and said: “Take this ring from Hertzog / and from mine as papal power / should you trust and connect with the sea / as a husband with his wives / strength of this pledge / and should do the same thing every year in the future / you and your descendants for a certain day ”. Otto was released from captivity on condition that his father be moved to peace. This succeeded, as the chroniclers unanimously reported, so that Friedrich went to Ravenna “after a safe conduct”, where Petrus Ziani, the Doge's son, met him with six galleys. The Pope was waiting for the emperor "in front of the church door H. Marci / sitting on a golden stul". Vianoli also describes the kiss on the feet and the subsequent elevation by the Pope, his kiss on the mouth, and, albeit softened by “a number of scribes wanting here”, the foot on the emperor's neck. Alexander is said to have quoted from the Psalms : " super aspidem & basiliscum ambulabis , about which the Kayser replied / non tibi, sed Petro , deme the Pope relocated / & mihi & Petro ". Then Vianoli's walk to the great altar follows, where the emperor asked for forgiveness and recognized Alexander as pope (p. 240). A small marble stone with a cross is said to have been sunk as a reminder where the two “Haubers embraced each other”. The Pope also decreed that the Doge, as the Emperor and Pope did, should always have a “heaven” projected. In addition, “to the more pomp” eight “silver trumpets and flags should be worn beforehand”. After all, the doge was supposed to seal his “Credentz letters” with lead instead of wax, “just like the papal bulls”, which was still common in Vianoli's time. "Now that the prince has come to an old age / and has presided over the Vatterland for six years without any problems / he canceled the world / shortly afterwards gave up his ghost".

For Jacob von Sandrart , "Sebastianus Zianus the Rich" in his Opus Kurtze and increased description of the origin / recording / areas / and government of the world-famous republic of Venice was only "chosen" in 1173 at the age of 70. He also counted him as the 38th Doge. This ruled therefore "eight years in peace". Since he had stood by the Pope against the Emperor “Fridericum Barbarossam”, “the Pope presented him with a golden sword / and other warm knight's mark / sambt a golden ring / with which he looked every year with the Hadriatic Sea / as with his Bride to marry / and therefore should constantly assert rulership over this sea ”. For Sandrart, Emperor Manuel I had the city "venerated" the three marble columns, "one of which was neglected and fell into the water / even bits anhero cannot be brought out / how they should be seen on the bottom" ( P. 37). Only one Lombard managed to erect the other two pillars. It was only there that it should be allowed to “play wrong with the dice”. At Sandrart, however, the Lombard only received a lifelong supply. The author, who sums it up briefly, also reports that during executions, for example when someone was convicted of having “had a hard time with the Turk”, a golden rod is placed on the pillars and the delinquent is executed with “golden rope”.

Beginnings of critical historiography up to the end of the Republic of Venice (1797)

Johann Friedrich LeBret published his four-volume State History of the Republic of Venice from 1769 to 1777 , in which he stated in the first volume, published in 1769, that “the eleven voters were chosen in a certain way, and they were given the task of choosing whoever they thought was the wisest and would keep the most legitimate ”, whereupon LeBret lists the names of the traditional Doge voters. After him, the voters were locked in a hall of the Doge's Palace. According to LeBret Orio Mastropiero received the majority in the first election . But this objected that one should choose a man who could raise part of the public expenditure on his own, and so he suggested Sebastiano Ziani. Thereupon he was elected and presented to the popular assembly, which recognized him by acclamation; for the nobility had not yet “robbed” the people of their rights, believes the author. "To sweeten his annoyance that he had not been allowed to take part in the election directly, he let himself be carried around the public square and threw a considerable amount of coins among the people" (p. 360). The people "began to like to wear the chain that was put on them because it was over-silvered." The new doge swore - "so far we have not noticed this from any of the doges" - "to preserve the freedom of the church." This is the first trace of the ducal promission ”, and only after this oath did the Primicerius hand him the ducal flags, and he was installed in the Doge's palace. He had the murderer of his predecessor executed, but “nothing worried him more than the burden of debt into which the state had been plunged by the previous prince.” “The treasury had to pay large sums of money, and the income was small.” Accordingly, “proved if all capital was with sequester, the administration of the funds was handed over to a procurator of the Heil. Markus, and satisfied the creditors with the assurance that as soon as the state had recovered somewhat, their requirements should be satisfied. ”LeBret describes this as“ the first state banquerot of the Venetians ”(p. 362) and also provides the Focus on the state's financial shortage. “Immanuel had humiliated her so far,” the author points out to the cause. At LeBret, the said two columns had come to Venice in a completely different way, namely not as a gift from Emperor Manuel, but they were booty from the punitive expedition of "Dominicus Michieli". They came from the "Islands of the Archipelagus" and were granite monoliths of the same size. But Venice found no one who was able to erect the two remaining columns - one of which had already sunk into the sea. The Lombard "Nikolaus Baratiere" was able to do this, but demanded that cards could be played among them, a place that was only rededicated as a place of execution under Doge Gritti. Allegedly from then on, the Lombard trained in "architecture and mechanics" and received a lifelong "salary", just like his descendants. “Venice owes its Rialtor Bridge to this school,” claims LeBret. - When Emperor Manuel realized that Venice could hardly react due to a “lack of money”, hit by the plague, he threatened the ambassadors that Ziani's predecessor had sent to Constantinople to “destroy” Venedi. “And Heinrich Dandulus, who, as a bold patriot, had answered him freely, frightened him by quickly and unexpectedly holding up a glowing metal, and almost completely robbed him of his face. The steadfast Dandulus generously endured this barbaric violence, and hastened with his colleague to Venice ”(p. 363). To regain freedom of trade, Ziani sent three new envoys, but they reported that the emperor had no real interest in a peace treaty. The Doge sent said Dandolo and Johannes Badoer to Wilhelm of Sicily in order to make an alliance against Byzantium. Now imperial “ambassadors” traveled to Venice, but to no avail, and the new legation of Venice did not achieve any results either. Meanwhile, Byzantine diplomacy incited Italy against Barbarossa, especially Italy. When Archbishop Christian von Mainz moved against the city, Venice supported him in this project. According to LeBret, it was Christian who advised Barbarossa "to win this republic" and he also induced the Doge to send an envoy to the Emperor to "establish an everlasting peace with the Doge and his successors" (p. 364) . - Ziani called a people's assembly to get his proposal to reorganize the internal situation approved. So “Justiciarii” were determined, “who got their name from the justice that was to be observed in daily trade.” They supervised the craftsmen, set their wages, decided as judges in disputes between them, like them Supervised "general stores", weights and measures and collected the fees for the shops. "The abundance of grain and flour is of the utmost importance in every state, especially in Italy," states LeBret (p. 365). "That is why grain and flour magazines were set up in Rialto as early as the time of Ziani, and the same three overseers were appointed" who also kept the accounts for imports and exports. The Ternaria monitored from now on oil and cheese, like all fat-containing products, and imports were higher burdened by tariffs as its own products. As with many historians of this epoch, the later conditions are also projected back into the past with LeBret. Venice soon brought in more money for the treasury than all other cities put together, the author continues. Three men each supervised the wine, the butchers, "the import of the horned cattle" in a similar manner. - Ziani broke new ground in terms of foreign policy. So he made an alliance with the former permanent opponents, the Normans of southern Italy. Even in this situation it was not possible to reach an agreement with Byzantium. Venice's merchants were given privileges in the Norman Empire, negotiations with Emperor Manuel were broken off, Venice allied with Rimini against Ancona, which was allied with Byzantium. "Suddenly, however, Venice became the stage on which half the world turned its eyes," says LeBret. After the defeat in the Battle of Legnano, Barbarossa sought a peace treaty. LeBret refers to Andrea Dandolo's chronicle when he states that the Pope spent the last night before the negotiations “in the monastery of Heil. Nicholas stays overnight ”. After he was solemnly "fetched to the city by the Doge, the Patriarch, the clergy and the people, and with the greatest solemnities in the Church of Heil. Markus led ”, the palace of the patriarch was assigned to him“ as the honorary quarters ”. The Venetian historiography reports, so LeBret, about it quite differently (see above), but this is a story "which was written for the mob of Venice". "Sandi, who writes for the reasonable world, does not defend this fairy tale either" (p. 368). Venice was only recognized as a place of negotiation in Ferrara , and the Pope returned there on May 9th. The story according to which Alexander III. Allowing the Venetians to use lead on their seals contradicts the fact that the Doges did so before. The victory of the fleet against Otto was invented in a similar way, but "Venice stubbornly asserts the truth of this victory, and finds a special state interest in praising it as true for posterity" (p. 370). The leaden seal on the Doge's letter was only intended to show the emperor that he was in league with the Pope, other events in the legends were intended to explain state institutions, such as the fact that there was a “prince's candlestick” that was placed on one white candle handed over to the Doge by the Pope, or the fact that the Doge was carried the sword in the scabbard, which should, however, symbolize the disempowerment of the Doge by the Senate rather than the donation by Alexander III. went back.

In particular, however, one could explain the marriage of the Doge with the sea , which Alexander should have donated out of gratitude for the victory over the fleet of the emperor's son Otto. But LeBret mistrusts the presentation as a whole, because not a single important prince was accompanied by Otto: “Whether it seems very questionable to us that the story only mentions the name of the prince without naming a single great gentleman who was caught in his entourage has been taken ”(p. 372). Otto, ready to work towards a peace with his father, “gave his word of honor that he would return to prison if his efforts were fruitless.” LeBret explains that the first to ignore the story was Caesar Baronius ( Cesare Baronio , 1538–1607), whose Annales ecclesiastici for the events around 1177 was based on the chronicle of Romuald , the Archbishop of Salerno , and a manuscript he discovered in the Vatican (p. 373). Since the popes followed this view, after LeBret there was a diplomatic conflict with the Republic of Venice, where an attempt was made to prove the historicity of the naval battle between Otto and Ziani's fleets using inscriptions, paintings and older historiography. “The safest time is the year 1484, from which time no one has contradicted history itself. Yes, this critical war even caused its own congregation of Cardinals at the papal court itself. "The Venetian ambassadors had pushed the matter so far in Rome that the corresponding words were restored under a painting by personal instruction of Pope Innocent (p . 375). - Otherwise the Pope stayed with LeBret in Venice until September 18, the Doge even visited the Pope in Rome. Alexander said goodbye to Ziani with another present, a gold-plated armchair. But it was true of the Doge: “Soon he was a loyal promoter of the federal cities when he saw that Frederick was becoming too powerful; soon he made a special peace with the emperor when he saw that he thereby gained advantages ”(p. 379). However, Ziani died on April 13, 1178, one day after he moved to the monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore. “He had supported victims with his fortune; he had improved the taste in architecture among his people ... he had bound the customs of his people to certain rules ”. According to LeBret, the procurators of San Marco were mainly used to build up and manage assets for the benefit of the poor. An inscription was placed on the grave, which he himself built during his lifetime, "which was unworthy of such a great man" (p. 380).

The historicity of the Battle of Salvore was still defended in Venice in 1785 , although the author is not sure whether the Venetians referred to the father or the son when the fleet leader "Ziani" was used. To this end, the author tries to question the credibility of the sources, in particular the authorship of Romuald of Salerno, and, should the archbishop nevertheless have been the author, he was in any case Norman and thus an enemy of Venice. Hence his silence in a matter that is glorious for his enemies is of no importance (p. 90 f.). In contrast, the author lists a number of (much more recent) inscriptions, but also the Chronicle of Andrea Dandolo, paintings in the hall of the Great Council in the Doge's Palace, as well as a painting in Siena in the Palazzo Pubblico , but also in Augsburg , but above all numerous chronicles; Finally, he adds the aforementioned Roman painting, which, following pressure from Venice, received the description of the battle back. In order to make the very young Otto plausible as a fleet commander, he follows the earlier dating of Otto's year of birth from 1163 to 1159, which means he was 18 years old according to his explicit opinion. For for him the battle, in contrast to the year 1174 mentioned in his own heading, now took place in the year 1177 (p. 97). To the assumption of his opponents that the empire did not have a fleet in the Mediterranean, he replies that it was probably a question of ships from the Italian sea cities, i.e. from Genoese, Pisan and Amalfi .

After-effects of the Venetian tradition, modern historiography

Less educative and moralizing than LeBret, but given a more national tone, Samuele Romanin interpreted the sources for this epoch, which were already less meager; In addition, he used a number of manuscripts from the Venetian archives and libraries that had not yet been edited at the time. In doing so, however, he took uncritically much later information from manuscripts that he had viewed, especially with regard to the inner constitution of Venice. At the same time he occasionally used Byzantine chronicles. In any case, he tried even more to classify the references to the Doge's life in the wider historical context, as he showed in the second of ten volumes of his Storia documentata di Venezia , published in 1854, on over 30 pages. The author justifies the break with the constitution practiced until Ziani's election with the fact that the Doges had succeeded in undermining the moderating power of their “consiglieri” by influencing the occupation until only “submissive” advisers were available whose convocation was in the power of the Doge. So it is not surprising that they never appear in the documents. On the other hand, the influence of the people's assembly was reflected in tumults and acts of violence. It took a good six months before a corresponding change could be implemented (p. 89 f.). According to Romanin, two councils were appointed from each sestiere to carry out the doge election. Each of them elected 12 men, making a total of 480 elected people. From then on, these were to assign the offices of the republic and submit laws to the people. Expressly following Gianantonio Muazzo (1621–1702), he believes that at this time the “Consiglio de 'Pregadi” had already been established, which prepared the drafts for voting for the 480, the Grand Council; later he was called "Senato". He admits only in a half-sentence that this institution was only stabilized under “ Giacomo Tiepolo ” (p. 92). As was so often the case during this period, the constitutional relationships were projected too far back into the past. Also, the author continues, four more have been added to the councils to limit the Doge's power. In addition, he had been expressly forbidden to obtain economic advantages for himself and his family in contracts with foreign powers, as Orso I. Particiaco - with Romanin "Orso Partecipazio I" - had done. As compensation for the loss of power, “la pompa esteriore”, “the external display of splendor”, has been increased. Here, too, Romanin preferred later developments, such as the swearing-in of the people on the Doge every four years, a ritual act that the Capi contrada , the heads of the parishes, took over (p. 92). From “varie Cronache”, as Romanin notes, it can be inferred that there had been considerable, noisy resistance to the changes in the electoral law; the councils were called “tiranni e usurpatori” and they wanted to exclude the people from the Doge election. After tumults, which were not easy to calm down, it was possible to make it clear to the people that the presentation of the new Doge secured the right to have a say, especially since the latter with the words “Questo è il vostro Doge se vi piace”, “This is yours Doge, if you like it 'was presented to this people. Here Romanin explicitly follows the Chronicon Altinate , the people finally acclaimed: "Viva il doge e Dio voglia, ch'ei ci procuri la pace" - the focus was therefore on peace. Now Romanin reports that the newly elected Doge was lifted by some on his shoulder and carried across St. Mark's Square; As a thank you, Ziani threw large quantities of coins into the crowd - but the permitted amount of coins, here the author Sansovino (“Venezia descritta”), was limited to 100 to 500 ducats (p. 95). But the first concern of the new Doge was the punishment of the Doge killer Marco Casolo , who was taken out of his hiding place and hung up, his house in the “Calle delle Rasse” was torn down and, as “un decreto” stated, it should never be returned stone house arise. Also, every future doge on the way to San Zaccaria should no longer go over the Riva degli Schiavoni , but over the "via de 'Santi Filippo e Giacomo", which Romanin took from the Delle Inscrizioni Veneziane Cicognas (p. 96, note 3; Romanin explicitly refers to Vol. IV, p. 566). The aforementioned Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna expresses doubts about this provision on the same page, but does not mention the Romaness. Quoting Andrea Dandolo, the author believes that the repayment of the bonds should have been postponed, but specifies that these would be necessary for the further fight against Emperor Manuel and for the support of the Lega Lombarda. This time, referring to Caroldo (p. 97), he barely lets Enrico Dandolo , whom the emperor hated, to escape. However, when it comes to Manuel's alleged blinding of Dandolo, Romanin also expresses doubts, because his blindness is no longer mentioned later when he was Doge; he himself mentions his age during the crusade speech of 1202, but not his blindness. Although the Byzantine chronicler Niketas mentions that Dandolo was blind, he does not mention that this was due to an imperial order. A settlement of the conflict with Byzantium had probably failed despite a new embassy (p. 97 f.). In contrast, the ambassadors “Aurio Mastropiero” and “Aurio Daurio” succeeded in signing a 20-year contract with William of Sicily in September 1175. Romanin emphasizes free trade for the Venetians, the halving of taxes, legal security, but above all that pirates and those who traded with Byzantium should be excluded from the Norman Empire (p. 98). The Doge had the said besiegers of Ancona support them, but they failed, so that the Venetians also had to withdraw. Then the author describes the development up to the Battle of Legnano (pp. 99-101), then the negotiations between the emperor and the pope. The route that the latter took to Venice is documented across the board through Philipp Jaffé's Regesta Pontificum. Contrary to the legendary assumption that the Pope arrived in Venice in secret and much earlier, Romanin also proves from the "Altinate" that Alexander III. was solemnly received by the son of the Doge and the “principali” of the city (p. 103 f.). According to Romanin, the Pope resided in the Patriarch's Palace near San Silvestro. Bologna was too hostile to the emperor as a place of negotiation, so the Pope should choose a suitable place. Initial negotiations about the venue threatened to fail in Ferrara, where the Pope appeared on April 10th. On May 9th he embarked for Venice, there, in a safe city with sufficient resources, as Romanin again deduces from the Altinate , the negotiations should now take place (p. 105). On July 24, 1177, the Emperor, Doge and Patriarch met on the Doge's ship to travel from San Nicolò with a large crowd on numerous ships to St. Mark's Church, where the Pope was waiting for them. The emperor kissed the pope's foot, but when Alexander raised him up, the kiss of peace followed. The “ratificazione” of the contract took place on August 1st (pp. 106-108). In a postscript, Romanin mentions that the contract with Sicily has been extended by 15 years. On September 16, a treaty was also signed with Venice, in which the emperor and doge granted their traders free access under the usual taxes, granted legal security, but above all the emperor forbade his "sudditi" to trade outside of Venice. Romanin sees in this the recognition of a kind of rule over the Adriatic (p. 109), but the emphasis was rather on the brokerage role that began in Henry IV in all trade between the Roman-German Empire and the eastern Mediterranean. Finally, Romanin complements the numerous privileges that Venice's churches received from the Pope. Romanin describes the legend as clearly wrong, according to which Alexander was supposed to have allowed the Doges of Venice to use a lead seal, because this had already been used by his predecessor (p. 109 f.). After a detailed description of the Doge's marriage to the sea, the author adds how a “concordato” ended the dispute between Grado and Aquileia. Enrico Dandolo, Patriarch of Grado, waived all restitution of the stolen property since 1016, Grado retained the obedience over the dioceses of Istria and in the Ducat Venice. The emperor finally left Venice at the end of September and the Pope in mid-October. According to Romanin, the detailed description and clear evidence should dispel all doubts about the course and significance of the event - above all the letters from the Pope and his surroundings - and at the same time free the tradition of legendary things. These popular stories are newsworthy - Romanin refers to Cicogna - and so he wants to defend them too. He tells of the Pope's flight via Zara to Venice, where he spent the first night on the bare floor of Sant'Apollinare, as a plaque there still shows, whereby other churches are also mentioned in the tradition - Romanin also refers here on Cicognas Iscrizioni . In the monastery of Santa Maria della Carità he was received as a simple chaplain , according to other versions as a scavenger boy ("guattero"). Accordingly, he was only recognized after six months by a French named Comodo. After his report, the Doge led the Pope to the Doge's Palace and provided him with accommodation in the Doge's Palace. When the negotiators Filippo Orio and Jacopo Contarini visited the emperor to start negotiations in Pavia, he claimed the extradition of the refugee, who was his enemy, from the Doge and - expressly - from the Senate under threat of war (p. 113). This is followed by the story of his 18 or 19 year old son "Ottone", whose fleet of 75 galleys, supported by Genoese and Pisans, was defeated by 30 Venetian galleys. The Pope gave the fleet commander a golden sword when they set out and blessed the company. An inscription in Salvore proves this victory at sea (p. 114). Otto was captured, but then generously sent to his father along with twelve envoys to start new negotiations. Now Friedrich was to receive a "salvacondotto" for the peace negotiations in Venice. But in Chioggia he had to wait until the end of the negotiations in order to be allowed to face the Pope only then. As "Obone di Ravenna", a contemporary reports, the Pope put the other foot on the neck of the prostrate emperor who kissed his foot, whereupon the well-known short dialogue ignited, which was followed by the kiss of peace. Here Romanin objects that Alexander's flight in 1167 can hardly be linked to his stay in Venice in 1177. The Pope also had no reason to flee at this time. Yet the author finds it difficult to believe that the Battle of Salvore was invented. As he notes in a footnote, name the “Cronaca Magno Cod. DXVI, t. IV, p. 79 ”even the fleet commanders, including Sebastiano Ziani as“ capitano general ”and numerous others. "Amiragio della dita armada" was a "Nicolò Contarini el zancho (il mancino)", that is, "the left-handed" (p. 116 f.). Romanin sums it up: 'So the Pope did not go to Venice in disguise, but in public ... he did not go to Ferrara to keep the Lombards in the league because they were far from breaking any treaty with the Emperor, they did not send their ambassadors together with Otto to Friedrich in Apulia, where he had not been since 1168 ... 'and the foot on the emperor's neck did not match the fact that he had returned to the lap of the church. Nor does this mention any contemporary source (p. 117). - Romanin also mentions the contract with Byzantium and the compensation payments that were agreed. This positioning in the extensive article fits in with the treaties concluded with Cremona (1173), Verona and Pisa (1175), but also with the measures for the internal order of trade and handicrafts, 'the interests of the people and public hygiene' ("Pubblica igiene"). At Romanin, too, all supervisory offices are set up under Ziani, as well as “poi i giustizieri vecchi e nuovi”. The urban development measures, especially the renovation of St. Mark's Square, had already started under Ziani's predecessor with the demolition of the Church of S. Geminiano. Now the new paving followed (whereby Romanin emphasizes), as old chronicles would report, Ziani bought a lot of land from the nuns of San Zaccaria. Where the Procuratie vecchie rise today , buildings of a similar shape would have arisen, as the author emphasizes after Sanudo. Some claimed that the two pillars were by Ziani, others that they had already been erected by his predecessor (p. 121). "Nicolò Barattieri", the Lombard who was said to have been the only one able to lift the two of the three submerged columns, appears under various other names in the chronicles, such as in the Barbaro Chronicle. There he was "maestro de 'Baradori e chiamavasi Nicolò Staratonius". Barattieri are cheaters today, so it was assumed that he was a card player. In any case, mechanisms are ascribed to him to be able to move material to the height of church towers (p. 122). Ziani's houses between the Mercerie and S. Giuliano were used to finance the feeding of prisoners, while the income from the houses of S. Giuliano towards Ponte de'Baretteri went to the monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore. A further seven congregations received grants. Ziani went to the monastery in question on April 12, 1178 at the age of 76, where he died. Shortly before his death, he once again changed the voting rights for his successor. The Grand Council was now to appoint four electors. These were Enrico Dandolo, Stefano Vioni, Marin Polani and Antonio Navigaioso.

In his Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia from 1861, Francesco Zanotto grants the popular assembly greater influence, but this people is always 'gullible because ignorant' ('credulo perchè ignorante') and 'fickle as the sea'. This manifests itself in "tumulti ed atti violenti" (p. 103), in tumults and acts of violence. Traditionally, twelve electors were chosen, two for each sestiere , with whom a multi-stage, co-determined voting process began. When eleven electors were to be used for the election of 1172, there was tumult, according to Zanotto, and it was difficult to convey to the people that this would not reduce their right to vote, now in the form of mere consent. The more the republic later became aristocratic , the more the people's right to practice medicine was completely given up ("ommessa del tutto"). The already popular Ziani threw money into the crowd after the election. First he arranged for the punishment of the assassin Marco Casolo , then he arranged the finances in order to be able to support the “lega lombarda”. So he suspended the interest payments that had been paid on bonds (prestiti). Allegedly the people demanded peace, and so the new Doge sent ambassadors to Constantinople, but he also made an alliance with William I and wrested its Italian base at Ancona from Byzantium. With him Venetians and Barbarossa's troops again besieged the city together, but Lombards and Romagnoles, collected by the "contessa Bertinoro" and the "Marchesello, signor di Ferrara", jumped in at Ancona, so that the Venetians had to leave at the beginning of winter. However, an alliance with Rimini forced the Anconitans to keep their gates closed. In the battle of Legnano in 1176 the communes triumphed over the emperor, "una delle più care glorie d'Italia", as Zanotto adds, one of Italy's most valuable acts of glory. The emperor was now ready to make a peace with him, and he wrote a letter to the Doge to mediate. Already in Anagni he had envoys negotiate his renunciation of the "scisma", and he now recognized Alexander III. as a legitimate Pope. He was traveling on a Norman ship, but, according to Zanotto, a storm brought him to the east side of the Adriatic, where he landed in Zara. So he went on to Venice, because a peace congress was planned there. There was neither a naval battle between the Venetian and the Roman-German navy under the emperor's son, nor did Alexander stay in Venice unrecognized - these processes, which had been handed down for centuries, were no longer mentioned. At Zanotto's, the Pope came to San Nicolò di Lido and was escorted to the Patriarch's Palace the next day. The said congress began in mid-May. When Friedrich came to Chioggia, many asked not to let him into the city, but the Doge let him in after he had signed a few stipulations, and Alexander also agreed. On July 23, six galleys also brought the emperor to San Nicolò in order to solemnly escort him to St. Mark's Square the next day through the doge, the patriarch, the clergy and the people. Friedrich took off all official regalia and threw himself on the floor, as Zanotto had described in the very traditional way, to kiss the Pope's feet; then he was picked up and he received the kiss of peace. Only he explains how the emperor took part in the Pope's service like a simple parishioner. Then he took up residence with a few of his followers in the Doge's Palace. The peace treaty was signed on August 1st, including a six-year armistice with the Lega, a fifteen-year-old with Wilhelm I. On September 16, Friedrich recognized all the privileges for the Venetians that his predecessors had issued. The Pope was also 'generous' to Venice because he consecrated three churches: San Salvatore, Santa Maria della Carità, the “cappella d'Ognisanti” in the Patriarch's Palace, which was resolved by San Silvestro. He gave the Doge the "Rosa d'oro", blessed by himself. Allegedly he also brought an end to the centuries-old dispute between the patriarchates of Grado and Aquileia . The emperor left the city towards the end of September, the pope in mid-October. This was one of the most 'glorious' moments in Venice's history, captured in twelve paintings in the Great Council room in the Doge's Palace and in one painting in the Council of Ten room (p. 106). According to Zanotto, a peace agreement had also been reached with Manuel I, the old privileges had been restored, the damage repaired and a sum of 15,000 gold ducats paid. The author adds that Ziani concluded trade agreements with Cremona in 1173, then with Verona and Pisa in 1175 , and in 1174 he founded the offices of the "giustizia vecchia" 'to protect the interests of the people'. All the other, much younger magistrates of Giustizia nuova are also founded with him . In addition, to beautify the city, he had the squares around San Marco enlarged and paved, had the "fabbriche" built around St. Mark's Square, restored and enlarged the Doge's Palace, and had the columns erected by Nicolò Barattieri (as he was now called), and through this also build the wooden Rialto Bridge . On April 12, 1178, Ziani renounced the dignity of the Doge in order to die the next day at San Giorgio Maggiore and to be buried there. Through his will he proved his piety towards God and his neighbor, because through his houses, which he owned in the Mercerie as far as San Giuliano , he provided bread to the 'poor prisoners'. From San Giuliano to the Ponte de'Baretteri, the houses went to San Giorgio Maggiore, whose monks were not only supposed to put up a candle, but also had to serve poor food, the details of which Zanotto lists. He also mentions the renovation of the church of the home parish of Doge San Geremia .