Orso I. Particiaco

Orso I. Particiaco , in the more chronological sources Ursus or Ursus Paureta , later also Participazio or Partecipazio († 881 in Venice ), one follows the so-called tradition , as the state-controlled historiography of the Republic of Venice is often called. Doge . He ruled from 864 to 881.

From 866 he fought against Slavic pirates on the east coast of the Adriatic , but also against Saracens who had established themselves in southern Italy and tried to do so on the eastern edge of the Adriatic. At Salvore, off Istria, the Venetian fleet suffered a defeat in 872, but won in 876 at Grado . The Narentans , also Slavic pirates, remained undefeated. Opposite the Carolingian Karl III. Ursus was able to contractually extend the provisions of the Pactum Lotharii that have existed since 840 with his demarcation. This renewal of the demarcation underlined Venice's independence. The Saracen attacks in the upper Adriatic were triggered by battles against the Saracens of Taranto , now the Saracens advanced from Crete to Grado. However, they dodged the Venetian fleet and plundered Comacchio instead .

Ursus received a high honorary title from the Byzantine emperor around 878, which contrasted with the renewal of the Pactum Lotharii concluded in 840 , which was an independent contract without Byzantium playing a role.

Ursus and his co-ruling son John have a ban on trading in slaves , albeit fruitless . More successful, however, was the establishment of the six Venetian bishoprics, namely those of Caorle , Eraclea , Iesolo , Malamocco , Olivolo and Torcello under the Grado Patriarchate . Its patriarch forced Ursus to flee, even against papal resistance. In the end, he even got his absent bishops recognized, even though he had been threatened with excommunication . Such influence in the ecclesiastical sphere became a matter of course for the Doges and at the same time a means of consolidating domestic power by appointing relatives and partisans. The intensity of the fighting was related to the fact that the Grado Patriarchate, whose borders in Italy coincided with those of the great empires there, threatened to become the gateway for their politics. This in turn was related to the fact that Grado had to defend his independence against the claims of the Patriarch of Aquileia , who tried to derive an obedience from the emergence of Grado. But this would have given the Venetian bishoprics one of the Carolingian greats or later an imperial prince as spiritual overlord.

Ursus had wetlands around the Rialto drained and promoted the settlement in Dorsoduro . He was buried in the Church of San Zaccaria . His firstborn Johannes followed him in office.

family

The Particiaco were among the most influential tribunician families in the early days of the Republic of Venice . Together with the Candiano and Orseolo , it was the Particiaco family - as the Venetian historiographical tradition has it - who provided most of the doges from 810 to the constitutional reform of 1172. The first doge of a Venice independent of Byzantium was Agnellus (810–827). He was followed by his sons Justinianus and Johannes (829-836). After the almost thirty-year reign of Peter (836-864) and his son Johannes Tradonicus († 863), the Particiaco and Ursus I returned to the Doge Chair. His son Johannes followed him. Other doges were Ursus II (911-932) and his son Peter (939-942) from a side branch of the family, the Badoer. In addition, several bishops and patriarchs came from the families of the Particiaco and the Badoer.

However, this alleged continuity is by no means assured. On the contrary, recent research assumes that the connection between the family to which Ursus belonged and the Particiaco was constructed in retrospect, and not until the 13th century. The main branch of Particiaco appears to have died out in 836 without a legitimate heir. For example, Ursus I and Ursus II - the latter was only made into a "Particiacus" by Johannes Diaconus around 1000 - at best come from a subsidiary branch of Particiaco. In any case, the Badoer succeeded in extending their lineage far into the past, namely into the time when Venice made itself independent of Byzantium, and thus an enormous gain in prestige.

The Doge's Office

It appears that Ursus was not involved in the murder of his predecessor; on the contrary, he continued his policy on essentials. He saw to the exile of the perpetrators, continued the civil and ecclesiastical reforms and fought the pirates, especially the Slavs in the upper and Saracens in the lower Adriatic.

In 866 he started a naval expedition against the Slavs. This was directed against Domagoj , who two years earlier had overthrown the legitimate pretender Zdeslav from the Croatian throne. Domagoj found himself willing to negotiate without a fight, and he released prisoners. But the peace did not last long, because in 872 the Venetian fleets were defeated at Salvore ( Savudrija ) off Istria . Trpmir , the son of Domagoj, who has since died, attacked a number of towns on Istria in 876 and then turned against Grado . This time the Venetians won. Finally, in 878, a treaty was signed with Zdeslav, who had succeeded in regaining power. Venice was willing to pay tribute for this. But the so-called Narentaner , another Slavic pirate group, has always escaped Croatian influence. They continued their pirate journeys. An attempt to stop them by force was unsuccessful.

The same applied to the Saracens, against whom both successes and failures occurred. Between 867 and 871, when Emperor Ludwig II attacked them in southern Italy, Venetian ships successfully attacked the Saracens of Taranto . But now the Saracens, who had conquered Crete around 826, attacked central Dalmatia . They advanced as far as Brač . In 875 the residents of Grado were able to defend themselves against an attack. A Venetian fleet, led by John, the son of the Dog, was able to repel their attack and deflect it against Comacchio . As a result, the trading competitor was plundered by the Saracens. They succeeded in conquering Syracuse in Sicily in 878 , with which the conquest of the island, which began in 827, came to a certain conclusion.

Overall, the successes of the Venetian operations, often in connection with Byzantine fleets and Carolingian land armies, increased prestige. From the Byzantine Emperor Basil I , Ursus received the honorary title of Protospatharius around 878 - probably from an imperial embassy on occasion , a title that no doge had ever received. The Carolingian Emperor Karl III. renewed the Pactum Lotharii concluded in 840 , which Lothar I had concluded with Petrus Tradonicus . This treaty established the state sovereignty of Venice, because it set its limits. Above all, however, it was a separate treaty without Constantinople playing a role.

In addition to external successes, Ursus is credited with a number of reforms. So new dioceses came into being in his time. The canons of the six dioceses of the ecclesiastical province of Grado were permanently established: Caorle , Eraclea , Iesolo , Malamocco , Olivolo and Torcello . But the attempt by state power to subordinate the ecclesiastical sphere also led to renewed tremors. In addition to the murder of Adeodato, the bishop of Torcello, in 864, this was particularly evident in 874, when Peter (Pietro I. Marturio), the newly elected Patriarch of Grado , initially refused the office and fled to the Kingdom of Italy. When the Doge saw that the Patriarch had rejected his candidate for election as Bishop of Torcello, Dominicus, Abbot of Santo Stefano di Altino , and threatened him with excommunication , he forced him to flee to Istria. After a year in Rialto , he even fled to Rome . Despite multiple interventions by Pope John VIII. Ursus forced the Patriarch Peter and his appointed bishops to give in. He only accepted the Bishop of Torcello, and this was also recognized by the successor of Peter. Peter returned to Grado and now consecrated the bishops appointed in his absence, whom he had not recognized until then. With this, the Doge achieved a fundamental turnaround in relation to patriarchy.

In January 880 there was also a treaty with the Patriarch of Aquileia . In it the Venetian traders in the port of Pilo were exempted from taxes. The Patriarch also promised an end to the hostilities on the part of Grado and renounced all claims to the dependent churches and their properties. An important long-term consequence was that the Doge proposed the candidates for episcopal, abbot and abbess offices until the 11th century and participated in the election, as well as exercising secular jurisdiction over the high clergy.

Together with his son and co-ruler Johannes, Ursus prohibited the trade in slaves , a prohibition that Pietro IV Candiano later renewed in 960. Contrary to short-term economic interests, the Doges preferred the reputation Venice gained with it. But they apparently had just as little success with this as the Pope with a corresponding ban.

In order to provide housing for the growing population of Venice, Ursus had the wetlands around the Rialto drained and encouraged the settlement in Dorsoduro . Andrea Dandolo proudly describes this, he sent the Byzantine emperor Basil I twelve bells to Constantinople, which were not known there and which had only been hung in the churches there since this gift. Possibly he saw in this a first compensation for the constant flow of high value goods from the Golden Horn into the lagoon .

The doge died in 881 and was buried in the church of San Zaccaria . He was followed by his firstborn John (usually called John II or Giovanni II to distinguish him from John I, the brother and successor of Justinianus), who ruled until 887.

reception

In the Chronicon Altinate or Chronicon Venetum , one of the oldest Venetian sources, which was created around 1000, the doge appears with the name and term of office “Ursus Paureta ducavit ann. 23 ".

For Venice at the time of Doge Andrea Dandolo , the interpretation given to Orso's rule was symbolic in several ways. The focus of the political leadership bodies, long established in the middle of the 14th century, which have steered historiography especially since Andrea Dandolo, focused on the development of the constitution (in this case the question of the formation of a conflicting dynasty, but also the derivation of one of the leading families in Venice), the internal disputes between the possessores (represented in the family names), i.e. the increasingly closed group of the haves who occupied political power and long-distance trade at the same time, but also the shifts in power within the Adriatic and the eastern Mediterranean as well as in Italy. The focus was always on the questions of sovereignty between the overpowering empires, of law from its own roots, and thus of the derivation and legitimation of their territorial claims. Added to this was the expansion of the growing city, in particular the creation and fortification of the islands, especially Dorsoduro . In addition, Ursus succeeded in subordinating the six suffragan dioceses of Grados, whose patriarchate was almost identical to the Venetian area.

The oldest vernacular chronicle, the Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo from the late 14th century, depicts the events on a very personal level that has long been customary at this time, which once again gave the Doges greater individual power. According to this chronicle, “Orso Badoaro, dicto Porecha” was raised to the status of doge by the whole people (“a voxe de tucto lo povolo fu elevado Duxe”). The identification of the Particiaco with the Badoer had long since become a matter of course. In Orso's time "Domago", the "primcipo de Sclavania" made peace with the "Comun de Venesia", while the "Saraini" attacked Dalmatia and all of Istria as far as Grado with a large fleet. The doge “cum li Venitiani” defended “tucte le contrade sue”. With the consent of the people, he made his son “Giane” a fellow doge “et constituillo suo successor nel ducado”, thus making him his designated successor. “At that time”, “Elicho, primicipo de Sclavania” caused great damage with its fleet. According to the editor of the chronicle, the author misunderstood Andrea Dandolo at this point or interpreted the adverb "Illico" appearing there as a proper name. In any case, the doge "personalmente cum grande exercito" went against him and won a victory. Finally, the Doge had "l'insula overo mota Dossoduro, essendo dexabitada" fortified and built on. Small, fortified islands are still referred to as Motta today, although the author believes that Dorsoduro was previously uninhabited. Some of these houses could still be seen at the time of the author of the chronicle.

Pietro Marcello reports with a few deviations . In 1502 he led the doge in the section "Orso Particiaco Doge XIIII" in his work later translated into Volgare under the title Vite de'prencipi di Vinegia . After the judgment of the conspirators who murdered his predecessor, Orso became a doge in 864 elected. Venice was threatened at this time by the "Barbari", including "Saracini" from Alexandria , who had conquered Crete and attacked Dalmatia from there , plundered the coastal fringe and besieged Grado. However, under Orso's leadership, the Venetian fleet drove away the attackers. 'Some reported another expedition' against Taranto. Contrary to the agreements, the Narentans robbed Istria, but the doge fought them happily. It was possible to repopulate Dorsoduro, which the inhabitants had given up because of the risk of looting. Marcello writes that the Doge had houses built there to house those who were in his service. They were therefore called the "Escusati de'Prencipi". After all, the Doge died in the 17th year of his reign.

The Chronicle of Gian Giacomo Caroldo tells of the 14th Doge, he was proclaimed Doge by the patricians and the people in 854. Without hesitation he drove, following the historical work completed in 1532, with the fleet against "Domogai Prencipe de Schiavoni", who declared himself ready for peace without a fight. Thereupon he drove against the "Saraceni", which he defeated before Taranto. Bari, 'possessed by Saracens for 30 years', was conquered by the army of Emperor Ludwig. In the following year the Saracens drove from Crete to “Brazza”, plundered several cities in Dalmatia, so that the Doge had them watched by a small ship. This was captured by "corsari Schiavoni" who attacked on small, hidden ships from an Istrian port. Two days before Grado, they evaded the Son of Dane and his fleet after they had looted places in the neighborhood. Johannes had to realize that he could no longer reach her and returned home. There he was made a fellow doge. At this time the Slavs plundered "Humago, Città Nova et Rovigno", but the fleet, led by the Doge, defeated them with 30 ships. The trade in slaves was forbidden "li Duci co'l 'Clero et Popolo", so it was forbidden by "the doges with the clergy and the people". At that time, according to the chronicler, the sons of Marin Pancratio "rinovare et ristaurare" left the church of Santa Maria Formosa , which threatened to collapse because of its age. The doge's preferred candidate for the patriarchal chair was "per commesso errore, gli furono tagliati li testicoli", and he was then "andato vagabondo". The contestants agreed in Ravenna that "Dominico Caloprino eletto Vescovo Torcellano per certo tempo fusse privo della consecratione, mache però havesse et possedesse la Casa et li beni del Vescovato". Dominicus, the elected Bishop of Torcello, should therefore own his house and the goods of the diocese, although he was not consecrated. The chronicler also briefly describes the dispute with the Patriarch of Aquileia.

In the Chronica published in 1574, this is Warhaffte actual and short description, all the lives of the Frankfurt lawyer Heinrich Kellner in Venice , who based on Marcello made the Venetian chronicle known in the German-speaking area, is "Orsus Partitiatius der Dreytzehende Hertzog". He was “Hertzog elected / in jar 864” after the “community was breastfed against”. This reassurance after the murder of his predecessor came through judgments of "the three men" who were intended to atone for the crime. The Doge's government “is pretty well approached / although the community was plagued by the Barbaris”, the Saracens who “had taken the island of Candiam in Dalmatia ... and besieged Grado” - here Marcello Candia meant, like the island of Crete and theirs Capital of the Venetians. However, under the leadership of the Doge, the fleet managed to force the "Barbaros to flee through research". Then Kellner reports of a victory over Taranto, which was followed by another after the Saracens there “contrary to the established treaty ruined a number of places in Istria”. "Around the same time Dorsoduro began to be inhabited / which was previously completely deserted / because of the robbery / which happened on the sea." For the new settlers planned there by the Doge's order, Kellner expressly mentions "Gli Escusati de Prencipi" - through diminished Scripture marked as a quote - that is, the “princes excused”. Kellner explains this expression with “just because they were waiting for the prince / and for that reason they were free and excused from all other complaints.” Orsus, “who ruled very well” died “in a great misfortune / in the seventeenth year of his own Hertzogthumbs. "

In the translation of the Historia Veneta by Alessandro Maria Vianoli , which appeared in Nuremberg in 1686 under the title Der Venetianischen Herthaben Leben / Government, and Die Die / Von dem Ersten Paulutio Anafesto an / bis on the now-ruling Marcum Antonium Justiniani , the doge was already called "Orsus I. Baduarius the Fourteen Hertzog". Both the numbering of the Doges and the assignment of Ursus to the Badoer family, or the equation with the Particiaco, became standard. According to Vianoli, under Ursus, “all activities and general state affairs were still pretty much over”, one ignores the threat posed by the “barbarians”. Allegedly the doge had the murderers of his predecessor seized, "of whom he also got four hands". As a deterrent "example" he had them "publicly / on St. Markus-Platz / first grinded / peened with red-hot tongs / cut whole pieces of meat out of their bodies / and finally let four horses tear them into pieces alive". But the doge could not turn to the internal quarrel, as the Saracens, Dalmatia and Istria plundered him, and Pola "had been dragged", now besieged Grado. Ursus hastily put together a “ship armada” which he himself commanded. He chased the Saracens to flight. Now, according to Vianoli, the Saracens attacked the "Greek Empire", which "became weaker day by day". They conquered the island of Candia, ie Crete, and the emperor asked the doge to take command of the "Greek Armada" (p. 106). He agreed to do this, whereupon he won a great victory against the Saracens of Taranto. After his return, Ursus settled the island "Orsoduro" (actually "Dorsoduro"). The new residents were called, as Marcello had already noted, “excusati del Principe”, “that is the prince's excuse”. He explains this with the fact that they "had to attend to the Prince's person every day / and were therefore single and released before all other complaints". In 881 the late Doge was followed by his son "Johannes II. Badoarius".

In 1687 Jacob von Sandrart wrote in his work Kurtze and an increased description of the origin / recording / areas / and government of the world-famous Venice republic , albeit very laconic: "Ursus Partitiatus". In 864 he was chosen as "(XIII. Others say the XVI.) Hertzoge". The Saracens "who set Ancona on fire / captured the Creta Island / and bit into Dalmatia / defeated with a very remarkable defeat / and Italy so far retired." For this he received the title of "Protospatharii".

According to Johann Friedrich LeBret , who from 1769 onwards in his four-volume State History of the Republic of Venice entertained his readership with his ornate rear projections - this only applies to the earlier Doges - who often "supplemented" the laconic and difficult-to-interpret sources, it was " Ursus Participatius ”about a man who was elected because someone was needed who“ would be able, given the prospects at that time, to protect them against all grazing peoples and against the violence of the Saracens ”. According to LeBret, the Particiaco were "popular with the whole people" because they had embellished the city with various buildings. “Agnellus and Justinian Participatius had immortalized their memory through beautiful foundations. Some bishops from this house had listed churches from their property ”(p. 171). But the Croats and Saracens seemed to act in concert. The Doge "compelled their prince Domogoi, or Dominicus, to compensate for the damage, to give hostages, and to come to terms with a peace." LeBret sharply criticizes that the Venetian merchant viewed the acts of violence of the Slavs and Saracens "with cold blood", he “negotiated the Christians made slaves by the pirates” and sold them to “whoever paid them best.” “The secular arm forbade this ungodly trade in Venice”. “Ursus rose above all considerations of private benefit, and preferred the interests of the state to it.” He had to “cleanse” the sea, which he succeeded in using “ships built according to a very different theory” against Taranto, and “because he was Volk had taught for the first time to conquer the most powerful enemies through bravery and skill. ”On land, Bari was called by“ K. Ludwig the second captured ”. In return , the Saracens of Crete plundered Brač , whereupon the Doge sent out a small, 14-man spy ship. However, this ship was captured by Slavs, the crew killed. “The Saracens ventured as far as Grado”, which was only noticed in Venice because of the said capture when the enemy ships appeared in front of the city. The siege lasted only two days because the doge gave his son Johannes orders to relieve the city. The mere appearance of the Venetian fleet caused the besiegers to withdraw and attack Comacchio instead . The son of the Dog returned "with the glory of a victory that had cost him nothing more than to show itself." Nevertheless, the people allowed his elevation to the rank of fellow doge. As the Carolingian Empire fell into disrepair, Venice's main enemy was piracy. But with thirty ships the Doge won a victory over the Croats who had destroyed Sipar , Emonia , Rovigno and Umago . The Narentans stayed away from the ensuing peace, against which even another navy could do nothing. According to LeBret, Ursus first made their use known in Byzantium with twelve bells that he gave to the emperor (p. 175). Dorsoduro was "made habitable through his care". "His hometown" Eraclea, where he had a palace built for his family, also benefited from his urban development measures. "His people adored him and had special respect for him, that it allowed him to die in peace." "His son John followed him without any contradiction" (p. 176).

Samuele Romanin granted "Orso Partecipazio, doge XIV" in 1853 in the first volume of his ten-volume opus' Storia documentata di Venezia ten pages. The Doge was anxious to restore the honor of the republic, which had been damaged by so many defeats. So he forced the peace by a naval train against the Croats, and the alliance of the Carolingians and the Byzantine emperor defeated the emirate of Bari . At the same time, the Venetians defeated the Saracen fleet of Taranto . But the two emperors fell out because of a failed marriage project for their children, which gave Romanin the opportunity to contrast the violence and injustice of feudalism with the sense of justice of the Venetians: “Ma in Venezia il feudalismo e le sue nequizie, il suo tirannico potere ed i suoi costumi non poterone mai penetrare ”(p. 193). Romanin even believed that the Venetians had enforced equal rights for everyone before the law (p. 193). He then reports on that spy ship that was captured by the Slavs and was no longer able to report on the activities of the Saracens, which in turn enabled them to appear in front of Grado as a complete surprise. As Andrea Dandolo had already reported and LeBret had written him out, the son of a Dog, from whose fleet the surprised Saracens had fled, also returned to Romanin, and he was immediately raised to be a fellow doge. Romanin describes the arguments with the clergy in detail, during the four years of which there were invitations to negotiations in Rome, which the clergy, however, did not comply with, whereupon the Pope warned the Doge to excommunicate. In the further course, the patriarch was forced to flee to Istria and then to Rome. On July 22nd, 877, John VIII called a synod in Ravenna, but the Venetian clergy arrived there too late. A compromise had been reached, but the event had shown how little the Doge himself was willing to accept papal interference in Venetian affairs. In the renewed battles against the Croats, the cities of Dalmatia and Zara joined Venice, as the Byzantine emperor could no longer defend them either. Therefore, the cities became practically independent under Emperor Michael II (820–829). But Romanin believes that peace was not possible in the long run with the many fragmented small empires of the Slavs. In the meantime, the slave trade, which had already been banned several times, was apparently continued, so that severe penalties were threatened again. But the prospects for profits were so great that they even prevailed over religion, humanity and the Doge's threats. Romanin doubts that Dorsoduro was completely repopulated, but those who once fled the pirates first built houses at the ports of San Nicolò and Murano, Dorsoduro became one of the sestieri of Venice (p. 197). With Aquileia, which has tried again to access the bishoprics of Grados, peace was concluded in a significant way. For the first time, the blockade of a mainland port, in this case Pilo, was enough to force a peace agreement. From then on, the Doge himself was even allowed to trade tax-free there. Romanin himself claims that he married a niece of the Byzantine emperor. His sons were either decisive in the secular sphere, or equally in the spiritual sphere, in this case through Victor II, the Patriarch of Grado.

August Friedrich Gfrörer († 1861) believed in his history of Venice from its founding to 1084 , which appeared eleven years after his death : “The government of the new Doge Orso Participazzo was a warlike one.” Gfrörer dated the first move against the Slavs on the basis of this the order of the descriptions in the chronicle of Andrea Dandolo in the years 864 or 865. Around 870 he sets the victory over the Tarentine Saracens, the attack of the Saracens on Grado around 876. Then he explicitly refers again to the said chronicle in the Description of the two-day siege of Grado, as well as of the fleet that John was supposed to lead against the besiegers, but which evaded and devastated Comacchio on the way back. In gratitude, the Venetians raised the fleet commander to be a fellow doge after they returned home. Although the Slavs let Venice's ships pass, they attacked other cities, which Venice would no longer tolerate. A peace agreement was reached afterwards, from which the Doge, however, excluded the Narentans, whom he punished. According to Gfrörer, the Doge prepared the future rule of Venice over Istria with this procedure. In addition, Charlemagne recognized that only Venice had the sea powers to keep the Slavic pirates in check. Only now, probably in the last year of Orsos, had Constantinople and Venice made contact again, and the Emperor had also accepted Venice's new role as a regulating power in the Adriatic. He had a high title and rich gifts to offer, Orso answered with those twelve bells. The reference to the palace in Heracliana (Eraclea), which Orso had built in the city of his ancestors, and the contractual provisions with Aquileia also come from Dandolo. According to Gfrörer, the patriarch Walpert (875-899) had made common cause with the Byzantine patriarch Photios against Pope John VIII , for which he received the supremacy over the dioceses of Istria and Dalmatia. The Doge "got into a dispute with the patriarch Peter von Grado, which turned out to be a prelude to the battle between Gregory VII and Henry IV of Germany" (p. 196 f.). By this Gfrörer meant the investiture dispute . "Yes! the patriarchs and bishops of Veneto had to dance as the Doge and later the Signoria played them ”- Gfrörer considers this action against the Church to be the cause of the downfall of the republic. In order to discredit the church, Dandolo included in his chronicle "one of the most malicious, but also the stupidest fairy tales that enemies of the Christian church have ever hatched", namely the story of Popess Joan (p. 198). In the dispute with Aquileia, in the course of which the Venetian bishops initially refused to appear before the Pope, they came too late to the Synod of Ravenna. They were therefore excommunicated. Johannes Diaconus writes that the Pope withdrew this excommunication at the Doge's request. For Gfrörer it is clear that the Doge must have threatened to join the Eastern Church in order to achieve this. As a compromise, the patriarch Peter was allowed to consecrate three elect, which he later did to the bishops of Olivolo, Malamocco and Cittanova, and as long as he lived, Dominicus should not receive ordinations. Dominicus was allowed to live in the bishop's palace until Peter's death and receive the associated income. At the age of 40, according to Johannes Diaconus, Peter died, as Gfrörer speculates, poisoned (p. 205). For Gfrörer, the initiative to ban the slave trade came from Peter and the clergy, by no means, as Dandolo claims, from the two doges. Dandolo saw, through and through Venetians, the clergy as the maidservant of the state and the Doges as the starting point for all initiatives - for Gfrörer this was the Byzantine relationship between state and church, “Byzantinism” par excellence. "After Peter's death, Orso had his own son Victor elected patriarch" (p. 207). But even he, forced by his father to ordain a castrati named Dominicus as bishop of Torcello, threatened the new bishop if he did not repent for forcing his election as bishop, which according to the laws of the Church would not have been due to him.

Pietro Pinton translated and annotated Gfrörer's work in the Archivio Veneto in annual volumes XII to XVI. Pinton's own account, which did not appear until 1883 - also in the Archivio Veneto - came to very different, less speculative results than Gfrörer. He sees Orso less as an anti-Pyzantine actor than as a doge who first and foremost organized the defense against pirates. At the same time, in his view, there was definitely a relationship of mutual support with Byzantium, as the joint attacks on the Saracens in Apulia would prove. According to Pinton, Gfrörer did not see the Byzantine title as a continuation of the good relations with Constantinople, nor did the emperor's rich gifts, mentioned for the first time, suffice for him. There is also no reference in the sources to Gfrörer's permission from Constantinople, which in his opinion is fundamentally necessary for all fellow doges. In the Carolingian sources, Pinton also holds Gfrörer inadequate knowledge of the sources, because he neither mentions the confirmation of the privileges from the year 880, nor the previous one from the year 875. He also does not know the probable confirmation from the year 870 by Ludwig II. Finally, when it comes to the ban on the slave trade, Pinton contradicts the assumption that Andrea Dandolo, out of hostility towards the church, concealed the fact that the patriarch was the author of the ban. On the contrary, Dandolo ascribes this credit to clergy and people alike.

As early as 1861, Francesco Zanotto had speculated in his Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia that the people gathered in Rialto had unanimously voted for the Doge. Otherwise, however, all of his initiative came from the Doge. After the settlement of the internal conflicts, the Slavs, who had expanded their territory and whose raids threatened Venice's security and trade, forced countermeasures, initially against Domogoi. Emperor Basilius had forged an alliance against the Saracens with Ludwig II and won the Venetians with a high title to strengthen the naval forces. But while the Venetians defeated the Tarentines, the two emperors had to withdraw after a year of siege. This gave the Saracens the opportunity to strike back as far as the central Adriatic. In the dispute over Aquileia, he sees the first cause in the fact that the Doge absolutely wanted to get his candidate Domenico Caloprino through. As a result of the expulsion of the Saracens from Grado, the son of a dog, Johannes, received "il consentimento della nazione di associarsi al padre nella ducal dignità" (p. 36). The author dates the attack of the Croats on Istria in the year 880. The reason for him is the "decadenza dei Franchi", the decline of the Franks. Although there was a treaty with the Slavs, Zanotto also sees the fragmentation and disagreement of the “tribù e zupanie” as the reason why no lasting peace was possible. With this author, the renewed ban on the slave trade was also initiated by the Doge. For the contract with Walpert, which he enforced without weapons and only by intimidation, "Orso received extremely generous praise from the historians."

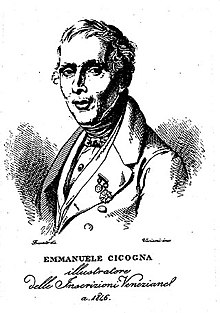

In 1867, Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna, in the first volume of his Storia dei Dogi di Venezia, expressed the view that after forty days of siege at the Doge's Palace, in which the bodyguard of the murdered Doge was holed up, the new doge was responsible for the selection of the said judges and for the punishment of the Culprits taken care of. He also describes the successes against Slavs and Saracens, whereby the Venetians returned from Taranto with captured ships and slaves. The fact that the Saracens evacuated the camp in front of Grado when they only heard of the approaching fleet is not mentioned by Cicogna and nebulously writes of Giovanni, the "si valentemente portossi in questo incontro", that he was rewarded by the people ("dalla nazione") Was made fellow doges. The doge issued the aforementioned ban on trading slaves, which was confirmed by the popular assembly, the concio . The two doges worked well together in the beautification of the islands, "alla felicità de'popoli" and in the expansion of Venetian trade in the end.

Heinrich Kretschmayr also believes that the Doge "probably comes from a branch line" of Particiaco. He considers Ursus to be a "continuation of the work begun by Petrus Trandenicus". He defeated the Croats, but the "Narentans, whose name from now on denotes the whole of the Serbs in Dalmatia, remained restless." According to Kretschmayr, the Venetians defeated Taranto "probably in autumn 871, half a year after the conquest of Bari by Emperor Ludwig II . ”The expulsion from Grado led to this author that it was not the people who raised the son of the Doge to co-regent, but the Doge himself. Since 867 Byzantium managed to intervene again in the Adriatic“ under the iron fist of the first Basilius ”, to win Bari and to set up the subject of Langobardia , so that around 880/881 the Adriatic in the south could be “considered pacified”. The contract with Karl III., Of which Kretschmayr writes "no longer some northern Italian cities with the permission of the emperor conclude an agreement with Venice, but the emperor himself for his Regnum Italiae" (p. 97), had considerably expanded the Venetian sphere of trade. In the contract with the Patriarch, the author considers the “granting of tax exemption for the Doge's personal trade” to be “the strangest”. “The head of state is a merchant like any other, and his position does not forbid him to conclude private business.” The “lost relations with the Eastern Empire” were “restored almost automatically” towards the end of his rule. The emperor “understood the difficulty, if not the impossibility, of forcing the socially and militarily thriving Venice back into its old dependency”. So he was looking for friendship, if not alliance. Similar to Gfrörer, Kretschmayr assumes that Venice “paid homage to the state church views of Greece”.

In his History of Venice , John Julius Norwich emphasizes that only tradition made Orso a member of the Particiaco. For him the judices , who were supposed to punish those guilty of doge murder, were the nucleus of a dogical court, and at the same time the end of popular rule. In contrast to this type of centralization of power (with the disempowerment of the tribunes that had once been entrusted to the Doge for control), Ursus pursued the goal of decentralization in church politics. In order to secure them from Aquileia, the cities of Caorle, Malamocco, Cittanova and Torcello were given their own bishoprics. When Ursus enforced special rights in proprietary trading with Aquileia, so Norwich, the face of Venice showed itself. The state might come first, "but enlightened self-interest was never very far behind".

swell

Narrative sources

- La cronaca veneziana del diacono Giovanni , in: Giovanni Monticolo (ed.): Cronache veneziane antichissime (= Fonti per la storia d'Italia [Medio Evo], IX), Rome 1890, pp. 117–123, 126 (“Domnus quidem Ursus dux, efflagitante Basilio imperatore, eo tempore duodecim campanas Constantinopolim misit; quas imperator in ecclesia noviter from eo constructa posuit, et ex tempore illo Greci campanas habere ceperunt. Mortuo vero hac tempestate domno Urso duce, dignitas in Iohanne su filo fuitio autemansit. Filo fuitio predictus Ursus multe sapientie et pietatis vir amatorque pacis ... "), 128, 178 ( digitized version ).

- Luigi Andrea Berto (ed.): Giovanni Diacono, Istoria Veneticorum (= Fonti per la Storia dell'Italia medievale. Storici italiani dal Cinquecento al Millecinquecento ad uso delle scuole, 2), Zanichelli, Bologna 1999 ( text edition based on Berto in the Archivio della Latinità Italiana del Medioevo (ALIM) from the University of Siena).

- Roberto Cessi (ed.): Origo civitatum Italiae seu Venetiarum (Chron. Altinate et Chron. Gradense) , Rome 1933, pp. 29, 117-125.

- Roberto Cessi, Fanny Bennato (eds.): Venetiarum historia vulgo Petro Iustiniano Iustiniani filio adiudicata , Venice 1964, pp. 1, 44-47.

- Ester Pastorello (Ed.): Andrea Dandolo, Chronica per extensum descripta aa. 460-1280 dC , (= Rerum Italicarum Scriptores XII, 1), Nicola Zanichelli, Bologna 1938, pp. 155-161. ( Digital copy, p. 154 f. )

- Alberto Limentani (Ed.): Martin da Canal , Les estoires de Venise , Olschki, Florenz 1972, p. 22 f. ( Text , edited by Francesca Gambino in the Repertorio Informatizzato Antica Letteratura Franco-Italiana ).

- Șerban V. Marin (Ed.): Gian Giacomo Caroldo. Istorii Veneţiene , Vol. I: De la originile Cetăţii la moartea dogelui Giacopo Tiepolo (1249) , Arhivele Naţionale ale României, Bucharest 2008, pp. 61-64.

Legislative sources, letters

- Roberto Cessi (ed.): Documenti relativi alla storia di Venezia anteriori al Mille , Padua 1942, Vol. II, pp. 7, 10, 13 f., 16-21.

- Capitularia regum Francorum ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , Legum sectio II , II), ed .: Alfred Boretius , Victor Krause , Hanover 1897, p. 138 ( digitized by Pactum Karoli III from January 11, 880 ).

- Karoli III Diplomata ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , Diplomata regum Germaniae ex stirpe Karolinorum , II), Berlin 1937, n. 17, pp. 26–31, here: p. 27. ( digitized version of the MGH edition )

- Paul Fridolin Kehr (ed.): Italia pontificia , VII, Venetia et Histria , 2, Respublica Venetiarum, provincia Gradensis, Histria , Berlin 1925, pp. 15-17, 44-47.

- Erich Caspar (Ed.): Registrum Iohannis VIII. Papae (Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Epistolae, VII, Epistolae Karolini aevi, V), Berlin 1928, p. 16 ( digitized version ), 18 f. ( Digitized version ), 24 f. ( Dig. ), 52 f. ( Dig. ), 55 ( Dig. ).

literature

- Marco Pozza: Particiaco, Orso I. In: Raffaele Romanelli (Ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 81: Pansini – Pazienza. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2014, (forms the basis of the presentation part).

- Michele Asolati: Una bulla plumbea del Doge Orso I Particiaco (864-881) , in: Rivista Italiana di Numismatica 117 (2016) 35-54. ( Digitized , academia.edu)

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Michele Asolati: Una bulla plumbea del Doge Orso I Particiaco (864-881) , in: Rivista Italiana di Numismatica 117 (2016) 35-54.

- ↑ La cronaca veneziana del diacono Giovanni , in: Giovanni Monticolo (ed.): Cronache veneziane antichissime , Rome 1890, p. 131 f.

- ^ Kurt Heller : Venice. Law, Culture and Life in the Republic 697-1797 , Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 1999, p. 663.

- ↑ La cronaca veneziana del diacono Giovanni , in: Giovanni Monticolo (ed.): Cronache veneziane antichissime , Rome 1890, p. 126: “Domnus quidem Ursus dux, efflagitante Basilio imperatore, eo tempore duodecim campanas Constantinopolim misit; quas imperator in ecclesia noviter from eo constructa posuit, et ex tempore illo Greci campanas habere ceperunt. mortuo vero hac tempestate domno Urso duce, dignitas in Iohanne suo filio remansit. ".

- ^ MGH, Scriptores XIV, Hannover 1883, p. 60, Chronicon Venetum (vulgo Altinate) .

- ^ Roberto Pesce (Ed.): Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo. Origini - 1362 , Centro di Studi Medievali e Rinascimentali “Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna”, Venice 2010, pp. 35–38.

- ↑ Pietro Marcello : Vite de'prencipi di Vinegia f in the translation of Lodovico Domenichi, Marcolini, 1558, p. 25 ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Șerban V. Marin (Ed.): Gian Giacomo Caroldo. Istorii Veneţiene , Vol. I: De la originile Cetăţii la moartea dogelui Giacopo Tiepolo (1249) , Arhivele Naţionale ale României, Bucharest 2008, pp. 61-64 ( online ).

- ↑ Heinrich Kellner : Chronica that is Warhaffte actual and short description, all life in Venice , Frankfurt 1574, p. 9v – 10r ( digitized, p. 9v ).

- ↑ Alessandro Maria Vianoli : Der Venetianischen Hertsehen Leben / Government, und die Nachben / Von dem First Paulutio Anafesto an / bit on the now-ruling Marcum Antonium Justiniani , Nuremberg 1686, pp. 104-107, translation ( digitized ).

- ↑ Jacob von Sandrart : Kurtze and increased description of the origin / recording / areas / and government of the world famous Republick Venice , Nuremberg 1687, p. 20 ( digitized, p. 20 ).

- ↑ Johann Friedrich LeBret : State history of the Republic of Venice, from its origin to our times, in which the text of the abbot L'Augier is the basis, but its errors are corrected, the incidents are presented in a certain and from real sources, and after a Ordered the correct time order, at the same time adding new additions to the spirit of the Venetian laws and secular and ecclesiastical affairs, to the internal state constitution, its systematic changes and the development of the aristocratic government from one century to the next , 4 vols., Johann Friedrich Hartknoch , Riga and Leipzig 1769–1777, Vol. 1, Leipzig and Riga 1769, pp. 171–176 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Samuele Romanin : Storia documentata di Venezia , 10 vols., Pietro Naratovich, Venice 1853–1861 (2nd edition 1912–1921, reprint Venice 1972), vol. 1, Venice 1853, pp. 190–199 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ August Friedrich Gfrörer : History of Venice from its foundation to the year 1084. Edited from his estate, supplemented and continued by Dr. JB Weiß , Graz 1872, p. 191 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ It is possible that Gfrörer was referring to a parallel process in Byzantium: Emperor Leo VI. forced the patriarch Photios to resign on September 29, 886 in favor of the sixteen-year-old Kaiserbrother Stefan.

- ^ Pietro Pinton: La storia di Venezia di AF Gfrörer , in: Archivio Veneto 25.2 (1883) 288-313, here: pp. 292-295 (part 2) ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Francesco Zanotto: Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia , Vol. 4, Venice 1861, pp. 34–37 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna : Storia dei Dogi di Venezia , Vol. 1, Venice 1867, o. P.

- ^ Heinrich Kretschmayr : History of Venice , 3 vol., Vol. 1, Gotha 1905, pp. 96-100.

- ^ John Julius Norwich : A History of Venice , Penguin, London 2003.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Pietro Tradonico |

Doge of Venice 864–881 |

Giovanni II Particiaco |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Particiaco, Orso I. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Partecipazio |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | 14. Doge of Venice |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 9th century |

| DATE OF DEATH | 881 |

| Place of death | Venice |