Giovanni II Particiaco

Giovanni II. Particiaco , in the more chronological sources Johannes (II.) , Later also Partecipazio or Participazio († after 887 ), was the 15th Doge of Venice according to the traditional Venetian historiography , i.e. the historiography controlled by the state . He ruled alone from 881 to 887, after having held the Doge's office together with his father Ursus I for a long time .

With John ended the Particiaco dynasty, which dominated the city from 810–836, then from 864–887 and finally, according to the historiography mentioned, from 912–942. The Badoer family, which possibly represented a side branch of the Particiaco, succeeded in securing this family as a prestigious ancestor around 1000. The importance of the tribunes declined sharply under John, and judices took over their role .

In terms of foreign policy, John II obtained from Emperor Karl III. 883 the renewal of the privileges that ultimately went back to the Pactum Lotharii of 840. The conquest of Comacchio , however, failed due to the resistance of the popes. Johannes' brother Badoarius or Badoer was fatally injured on the way to negotiations, and the Doge then had Comacchio devastated in 883. The excommunication forced the Doge to give up the city, which soon became a strong commercial competitor again.

The dynasty died out after his youngest brother Peter , who had already been raised to be a co-doge, died around 885, after which the remaining brother Ursus had resigned together with John. The Venetians now elected Petrus Candianus as Doge, a transfer of power that the Doge himself initiated. Johannes abdicated on April 17, 887, but his successor died five months later in a skirmish. John refused the demand to take over the Doge office again, so Peter Tribunus was elected Doge. Neither the tomb nor the year of death of John have been recorded.

The Doge's Office

John II Particiaco was the son and co-regent of his predecessor, whom he succeeded in office without election. During his short reign, the centuries-old role played by the tribunes largely disappeared . Only those families survived at the highest political level who had invested their fortunes profitably in trade and shipping. From a constitutional point of view , the tribunes were replaced by Giudici or Iudices . These were not legal experts, but men who enjoyed great political prestige and who could also represent the community.

In terms of foreign policy, John II obtained from Emperor Karl III. on May 10, 883 in Mantua the renewal of the privileges already renewed under his father Ursus in 880, which in turn went back to the Pactum Lotharii of 840. However, it was not possible to occupy the territory of Comacchio , which had not yet recovered from the sacking of the Saracens . Rather, a violent dispute arose with the popes over control of the papal-owned trade emporium near Ferrara . So John II sent his brother Badoer to negotiations with Pope Hadrian III. But Marino, Count of Comacchio, intercepted Badoer on the way to Rome , where he was injured. He sent the wounded back to Venice, but Badoer died immediately after his return (“statim”, as it is called by Johannes Diaconus ). In revenge, the Doge had Comacchio devastated in 883. When John made a new attempt at Hadrian's successor Stephan V to confirm ownership of the now occupied city, he received another rebuff. The city had to be given up after the excommunication of the Doge. In fact, it soon became a keen commercial competitor again.

Towards the end of his reign, a series of deaths wiped out the family after Badoer had died after 883. At first the doge raised his youngest brother Peter (Pietro or Piero) to be a fellow doge because he was sick himself, but he too, already acclaimed by the people, soon died at the age of 25. The remaining brother Ursus was also out of the question, because he resigned from office together with Johannes. According to the chronicler Johannes Diaconus , in view of this situation, the Venetians chose Petrus Candianus as doge. According to Johannes Diaconus, John II himself is said to have initiated this transition by making Peter co-regent. He himself abdicated on April 17, 887. When Candiano, for his part, died on September 18, 887 in a naval skirmish at the helm of twelve ships off Zara , Johannes was supposed to return to office. But he refused. Therefore, Pietro, the son of Dominicus Tribunus, was elected Doge ("Tribunus" was already interpreted by Monticolo not as a title, but as a name). We learn nothing about the further fate of the resigned Doge Johannes, except that he spent his last days in his palace (“ad domum propriam”). With him the Particiaco line ended. The Doge's grave is just as unknown as the year he died.

reception

For Venice at the time of Doge Andrea Dandolo , the interpretation given to the reign of John II was symbolic in several ways. The focus of the political leadership bodies, long established in the middle of the 14th century, which have steered historiography especially since the Doge and chronicler Andrea Dandolo, focused on the development of the constitution (in this case the question of transition in the context of attempts to form a dynasty, but also its derivation one of the leading families in Venice, the Badoer), the internal disputes between the possessores (represented in the family names), i.e. the increasingly closed group of the haves, who simultaneously occupied political power and long-distance trade, but also the shifts in power within the Adriatic and in the Eastern Mediterranean as well as in Italy. The focus was always on the questions of political independence between the disintegrating empires, of law from its own roots, and thus of the derivation and legitimation of their territorial claims. As with his father, this claim applied not only to the neighboring great powers, but also to the upper Adriatic and was directed against both Comacchio and the young Slavic rulers on the eastern shore of the Adriatic.

The oldest vernacular chronicle, the Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo from the late 14th century, depicts the events on a level dominated by individuals that has long been customary at that time, which once again gave the Doges greater power. According to this chronicle, “Zoane Badoer”, as he is already called, remained in office after the death of his father. The Particiaco's identification with the Badoer had long since become a matter of course. With the consent of the people, his father had made him a fellow doge, "et constituillo suo successor nel ducado", thus made him his designated successor. When trying to incorporate Comacchio into his rule, Johannes' brother Badoer fell into the hands of his opponents in the Ravenna area and was killed - according to the author. In a rage, Johannes let his army destroy the city of Comacchio at will. When he fell ill, "Piero Badoer, suo fradelo, coaiuctor et compagno nel seggio dugal constituì". According to this chronicle, he and his brother renounced the Doge's office together.

Pietro Marcello reports with a few deviations . In 1502 he led the Doge in the section "Giovanni Particiaco Doge XIIII", which was later translated into Volgare under the title Vite de'prencipi di Vinegia . Although Giovanni took over rule in 881, the Doge had already proven himself. Venice had been threatened by the "Barbari" for some time, including "Saracini" from Alexandria , who had conquered Crete and attacked Dalmatia from there , and finally even besieged Grado. According to Marcello, the Venetian fleet drove out the attackers under Orso's leadership - not under John's leadership. He also describes how Badoer was injured and captured, released after being sworn in, but then died of the injury in Venice (“morì della ferita”). In revenge, John conquered the city of Comacchio “con poca fatica”, “with little effort”. While he was punishing the guilty in Comacchio, he devastated the Ravennatic 'with iron and fire'. When Johannes fell ill, he raised his brother Pietro as his successor, but he recovered so that he was now a fellow dog ("lo prese per compagno nel governo della Repub."). After Pietro's death "si tolse in compagnia Orso suo fratello minore", he took his younger brother as a fellow doge. Together with his brother, ill, he withdrew from the Dogat.

In his Historie venete dal principio della città fino all'anno 1382 , Gian Giacomo Caroldo reports from the 15th Doge "Ioanni Badoaro", "il qual comi [n] ciò [sic!] Haver il regimento della Città et stato Veneto solo, l ' anno DCCCLXXJ “, so he had led the regiment alone from 871 onwards. He had previously done a great job, because two days before Grado the Saracens had evaded Johannes and his fleet after they had looted places in the neighborhood. Johannes had to realize that he could no longer reach her and returned home. There he was raised to be a fellow doge. He, his father, clergy and people together forbade the trade in slaves: "li Duci co'l 'Clero et Popolo". When he sent his brother to Rome to receive the Contado from Comacchio, Count Marino sent spies and had him arrested on the way back. In doing so, he dealt him 'a fatal injury', “una mortal ferita”. After taking the oath that he would not seek redress, he released him. But immediately after his return Badoer died in Venice. In a rage, Johannes had the city destroyed. He left his “Giudici” in the city “a quel governo”. He also took revenge on the Ravennates and caused great damage. In Mantua he obtained confirmation of the old rights from the emperor. When the doge became seriously ill, the people agreed that he raised his younger brother to doge. But he died a little later at the age of 25. He therefore raised Orso, another brother, to be co-doge, who founded the church of Santi Cornelio e Cipriano on the Lido di Malamocco in a place called Vigna. It should be subordinate to the "Cappella di San Marco". When the Doge fell ill again, he allowed the people to choose another Doge ("permesse al Popolo ch'elegesse un Duce che più li fusse grato"). John gave the elected Pietro Candiano "l'insegne del Ducato et sede Duce". With Orso the new doge went against the Narentans, but without success. Pietro, who started a new attack in August, died on September 17, 887, during which the Andrea Tribuno succeeded in securing his body and having it buried in the church of Grado. 'Of medium stature and 45 years old' - “di mediocre statura, d'anni XLV” - he had only been a doge for five months. Despite his illness, Johannes listened to the people's requests - "per soddisfare alle preghiere del Popolo" - to resume his office. After six months and thirteen days the "pubblici rumori" were so reassured that he was able to persuade the people to elect a new doge in 888.

In the Chronica published in 1574, this is Warhaffte actual and short description, all the lives of the Frankfurt lawyer Heinrich Kellner in Venice , who based on Marcello made the Venetian chronicle known in the German-speaking world, is "Johann Partitiatius the fourth Hertzog". Johannes, "Orsi Son / nam das Regiment an / im 881.jar". Ursus sent "his brother Badoerum to Bapst Johanne / to hand over Comachio to the Venetians." Marinus, "Graff zu Comachio", threw "Badoerum beyond Ravenna under / wounded in / and imprisoned." At the promise to head towards his enterprise the count released him, but Badoer died "shortly afterwards / when he came back home / from the stroke he had received." In revenge, the Doge won Comacchio "with little effort. Also punishes the very hard / so umb his brother Todt had with science ”. He also covered the “Ravignaner” with “Schwerdt and Fewer.” But soon he fell seriously ill and “made him the successor to Petrum / his brother”. But when, contrary to expectations, he recovered, he took him "as an assistant in the regiment". When Peter died, "he chose his younger brother Orsum as his journeyman". The doge fell ill again and so “he gave his brother a drink when he had not ruled for six years. And his brother Orsus lives for himself for a while and in private life. "

In the translation of the Historia Veneta by Alessandro Maria Vianoli , which appeared in Nuremberg in 1686 under the title Der Venetianischen Herthaben Leben / Government, und Die Aussterben / Von dem First Paulutio Anafesto an / bis on the now-ruling Marcum Antonium Justiniani , the doge is “ John II. Badoarius, called the fifteen-toe Hertzog ”. The equation of the Badoer with the Particiaco, beginning with Johannes' father, had already become the historiographical standard. According to Vianoli, who differs in some places from earlier historians, the father commanded the “ship armada” himself, which chased the Saracens away from Grado, not Johannes. In 881 his son followed the late Doge without further ado. There was therefore no connection to Grado, and certainly no elevation to the position of Doge during the father's lifetime. Johannes sent his brother "Petrum Badoarium, to Pope Johannem, after Rome". However, Count Marinus of Comacchio had him intercepted. At Vianoli the brother was not only called differently, but he also died in Comacchio, not after his return to Venice. In his "righteous anger" - about the consequences of an insult, Vianoli goes on almost two pages - the Doge "devastated everything with fire and grief after Ravenna"; also he had "made the entire Graffschaft Comachio submissive to his heated weapons" (p. 110). When the Doge soon became seriously ill, he “appointed” his brother as his successor ”, but when the Doge“ unexpectedly recovered / only headed the regiment as an assistant ”, and he too had“ his younger brother Orso the job arranged ". Vianoli recognizes the fellow Doges from their office again. When John “sensed / that he could no longer rule the community / because of a decrease in powers” he handed over “this high dignity of the princely throne” to Petrus Candianus.

In 1687 Jacob von Sandrart wrote in his work Kurtze and an increased description of the origin / recording / areas / and government of the world-famous republic of Venice also, albeit very laconically: "In the year 881. his son Johannes who gave the Ravennatern the city of Comaclum (Comacchio) removed by force ". When the Doge "fell into a fatal illness / and he avoided / that he would die / he asked the people / that his brother would like to be appointed as his successor". When he “came up again” “he used his brother as his co-regent; and as the same with death he took his eldest son with him with equal dignity ”. After six years of government he “felt” that “the people were not at peace with their government / so they both abdicated” (p. 21). The rule of the Doge is thus reduced to the conquest of Comacchio and the question of the title and succession.

In the four-volume State History of the Republic of Venice by Johann Friedrich LeBret , which was published from 1769, it is succinctly stated: "The Saracens ventured as far as Grado". But the siege only lasted two days because Johannes received orders from his father to relieve the city. The mere appearance of the Venetian fleet under his command caused the besiegers to withdraw and attack Comacchio instead. The son of the Dog returned "with the glory of a victory that had cost him nothing more than to show itself." Nevertheless, the people allowed his elevation to the rank of fellow doge. The Doge's "son John followed him without any contradiction" (p. 176). Unlike his father, he was "not obliged to draw his sword against them [the Slavs]". “The Bado family was so used to ruling that they looked for princely thrones for all four brothers. Drey sat on the Venetian throne ”, so Comacchio seemed appropriate for“ Badoarius ”. According to LeBret, the Pope saw Comacchio as so threatened by the Saracens that he was inclined to leave the city to the Venetians, who were the only ones able to defend it. The author knew that Marinus, the count who had him intercepted, injured him "very hard on the leg". Then he forced the prisoner to take an oath in which he waived vengeance. He was then taken to Venice, where he died. After a campaign of revenge, "he appointed judges as he pleased, and then went home again happily." He also had the Ravenna table “plundered”. LeBret is surprised that the Pope did not intervene, or at least prevented the Doge from raiding, but perhaps, according to the author, the Pope ceded the area under certain conditions, or that his supremacy was so little respected that one can safely claim one's rights could provide. From Karl the Fat, Johannes received confirmation of all privileges for five years, “but with the condition that the Venetians should allow themselves to be used to collectively cleanse the Adriatic Sea of the Slavic pirates or Croats who had withdrawn from the Franconian yoke. “The privileges valid since Charlemagne were also renewed for goods on the mainland. LeBret noted that for the first time conditions were set for this renewal, so that this renewal represented "a mere grace of the emperor". When Johannes fell seriously ill and was no longer able to run the affairs of government, he obtained the “consent” of the people to “appoint his youngest brother Peter as successor or government administrator” (p. 179). Even after recovery, the people “recognized” his brother as a permanent co-regent. ”However, when he died at the age of 25,“ [John] accepted the third brother as co-regent ”, but he too wished to“ withdraw ”from his dignity. So "Johannes finally gave thanks voluntarily". He called on the people to vote, from which Peter Candiano emerged victorious. John called him to the “ducal palace”, where he “gave him the ducal sword, the scepter, and the ducal chair, thereby recognizing him as his successor”. His behavior after his reign is particularly emphasized, especially after the surprising death of Pietro Candiano in 887: “As soon as John calm the unrest, fulfilled the wishes of the nation, and saw the throne occupied by a worthy successor, he returned to his philosophical calm returned, and all his conduct did him more honor than a thousand victories bought with human blood [...] He left the throne again, seeing his fatherland happy, lived as a philosopher, and died happy (p. 182 ). "

Samuele Romanin granted John II six pages in the first volume of his ten-volume opus ' Storia documentata di Venezia ' in 1853 . As Andrea Dandolo had already reported and LeBret had written him out, the son of a Dog, from whose fleet the surprised Saracens had fled from Grado, also returned to Romanin, and he was immediately made a fellow doge. In connection with the conflict between the Count of Comacchio and the brother of the Doge added Romanin that for a successful trade Comacchios the Venetians was a thorn in the side, on the other hand, that the county by Ludwig II. With diploma of 30 May 854 had been awarded to Ottone d'Este, for whom his son Marino led the government. Comacchio had also made available a fleet and auxiliary troops to Pippin's invasion army against the lagoon cities of what would later become Venice. According to Romanin, Marino had provided the captured Badoer with the best medical care and had given him the oath to refrain from annexation plans and sent him to Venice. Perhaps ("forse") died of the injuries suffered, revenge was demanded in Venice. Comacchio was occupied and destroyed, as was the land under the walls of Ravenna; own judices or 'consuls' to protect trade in Comacchio were installed. The renewed privilege of Charlemagne of 883 contained further provisions, such as the fact that imperial subjects were not allowed to use Venetian territory for their own purposes, that merchants were given free access to the empire as long as they paid the taxes ( teleoneo and ripatico ), of which the doge and his kin were exempt. Even in the event of an overthrow in Venice, provisions were made, such as the expulsion of those concerned and their accomplices, the setting of a very high fine of 100 libbre d'oro for those who violated the imperial regulations. Eventually the sick doge took his brothers, apart from Badoer, one after the other as fellow doges, but they either died or refused to lead the office alone.

August Friedrich Gfrörer († 1861) assumes in his history of Venice from its founding to 1084 , which appeared eleven years after his death : "Doge Orso died in the year 881 (or 882)." Then he explicitly refers to the said Chronicle of Andrea Dandolo when describing the two-day siege of Grado, as well as the fleet that John was supposed to lead against the besiegers, which however evaded and devastated Comacchio on the way back. In gratitude, the Venetians raised the fleet commander to be a fellow doge after they returned home. Only now, probably in the last year of Orsos, had Constantinople and Venice made contact again, and the Emperor had also accepted Venice's new role as a regulating power in the Adriatic. For Gfrörer, the initiative to ban the slave trade came from the clergy, by no means, as Dandolo pretends, from the two doges. Andrea Dandolo saw, through and through Venetians, the clergy as the maid of the state and the doges as the starting point for all initiatives - for Gfrörer this was the Byzantine relationship between state and church, “Byzantinism” par excellence. In addition, "there are reports that Orso's sons were men with weak nerves and inclined to infirmity." John II wanted to get "his brother Badoarius a substantial supply at the expense of the chair of Peter". The men of Count Marinus of Comacchio "hit" this man - while quoting Andrea Dandolo - "one of the legs in two". Only after swearing not to take revenge was he released to Venice. According Gfrörers the Pope took in the face of the nobility, to the Papal States , began to divide the seizure of Comacchio by Badoer in buying, "whose friendship was worth at least something." Gfrörer regards the contract with Karl the Dicken from 883, which provided for goods, duty-free trade, yes, protection from overthrow, as a sign of something else: the “Doge of Venetia recognized the Franconia as its master and took the Zealand off the imperial crown in fiefdom ”(p. 211). The Doge also retained jurisdiction over the "emigrants" who continually tried to overthrow the Doge while they were in exile in Franconia. These provisions are a kind of secret addition to the contract, which Muratori "referred" to in a footnote. Gfrörer suspects that John II turned entirely from Byzantium and turned to the Carolingians, also because his business was perhaps more likely to extend to the Franconian Empire - hence the tax exemption. Byzantium, however, by no means let the Doges have their way. Gfrörer claims "that the Greek party in Veneto forced the appointment of fellow Doges whenever Doges broke with Byzantium", but this ultimately failed because of Peter's death. Then the reinstatement of Johann followed, but since his alleged patron Karl the Fat had been overthrown, he could no longer hold his office. This also indicates that the election of his successor took place in his house and that John II only handed over the insignia of his power in the Doge's Palace afterwards. As always with Gfrörer, Byzantium was behind the appointment of fellow Doges and the resignation of the Doge.

Pietro Pinton translated and annotated Gfrörer's work in the Archivio Veneto in annual volumes XII to XVI. Pinton's own account, which did not appear until 1883 - also in the Archivio Veneto - came to very different, less speculative results than Gfrörer. He considers the doge's self-serving motive for the occupation of Comacchio to be one-sided, as the trade advantages for the whole of Venice would be suppressed. In the treaty of 883, too, Gfrörer underestimated the difficulties in which Charlemagne had found himself and who had by no means succeeded in outbidding Charlemagne in this regard. According to Pinton, the Doge, harassed by the greats of the mainland, could have stipulated that opponents such as the Ravennaten or those from the neighboring mainland should be subject to severe punishment. In any case, there is no indication of any kind of supremacy by Charles. After all, Gfrörer based his interpretation on an incorrect chronological sequence of events, because the Doge's resignation was at least three months before the death of Charlemagne, so that his resignation could not be linked to the end of his alleged overlord.

As early as 1861, Francesco Zanotto speculated in his Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia that Johannes wanted to secure “grandezza e potenza” for his family. As a result of the expulsion of the Saracens from Grado, the son of a dog, Johannes, received "il consentimento della nazione di associarsi al padre nella ducal dignità" (p. 36). And it was again the "nazione", with whose consent Badoario tried to appropriate the Comacchio county from the Pope. The author names the motif that the Count gave the Pope “motivo di noia”. With Zanotto it was again the people who demanded “vendetta” for the death of Badario, a revenge that ultimately led to the protection of the Comacchio trade under “giudici e consoli”. The confirmation of the old privileges by Karl the Dicken was "generous". He gives in detail the inexplicable natural events, storms and storm surges listed in the "Sagornina" (as the chronicle of Johannes Diaconus was still called at that time). Of the Doge's illness and of Pietro's death, the cause of which he does not name, he highlights the resignation of John II as a unique case. With him, this resignation and the election of a new doge came from the people.

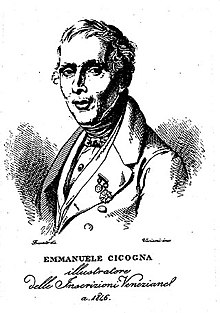

In 1867, Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna, in the first volume of his Storia dei Dogi di Venezia, expressed the view that John II had asked the Pope for Comacchio in order to increase the influence of his family. Under the section that Cicogna had dedicated to the Doge's father, the author conceals that the Saracens were about to evacuate the camp in front of Grado when they only heard of the approaching fleet, and writes nebulously of "Giovanni", the “Si valentemente portossi in questo incontro” that he was made a fellow doge as a reward by the people (“dalla nazione”). The two doges worked well together in the beautification of the islands, "alla felicità de'popoli" and in the expansion of Venetian trade in the end. Although the brother of the now sole ruling Doge received the county, he was attacked by the previous owner - Cicogna knows that Badoer defended himself as fiercely as he could - and injured so badly that he died in Venice. John subjected the city to the Venetian "impero". Neither the Pope nor the Emperor opposed the looting he had carried out against Ravenna. On the contrary, Venice received a renewal of privileges from Emperor Charles, and Cicogna did not forget to mention that the Doge's trade was not only permitted, but even without taxes. After the two further deaths in the family, Johannes finally resigned and left the 'nation' to choose whoever it liked as doge (“qual più le piacesse per doge”).

Heinrich Kretschmayr believed that the Doge "probably came from a branch line" of the Particiaco. For this author, the expulsion from Grado meant that it was not the people who raised the son of the Doge as co-regent, but the Doge himself. Since 867, Byzantium managed to intervene again in the Adriatic "under the iron fist of the first Basil", to win Bari and the subject To set up Langobardia so that around 880/881 the Adriatic Sea in the south could be “considered pacified”. "The development was heading more and more towards a supreme power inherited in the house of the particiaci" (p. 100). Kretschmayr put the fight for Comacchio in the foreground.

In his History of Venice , John Julius Norwich emphasizes that only tradition made John's father a member of the Particiaco. Otherwise he limited himself to the illness-related appointment of fellow doge Pietro Candiano, who was the first doge to be killed in a battle on September 18, 887. Finally, the author mentions John's return to office in order to determine his final successor. He hardly dedicates a half-sentence to his renewal of privileges by Karl the Fat and places them in a continuity of constantly expanding rights in Venice. The fight for Comacchio is not mentioned.

swell

Narrative sources

- La cronaca veneziana del diacono Giovanni , in: Giovanni Monticolo (ed.): Cronache veneziane antichissime (= Fonti per la storia d'Italia [Medio Evo], IX), Rome 1890, p. 121 (Siege of Grado), 122 ( Mitdoge), 123 (peace treaty with Croats), 126–130 (successor to his father, death of Badoer, resignation, death of Peter, end of the reign), 178 (“Catalogo dei dogi”) ( digitized version ).

- Luigi Andrea Berto (ed.): Giovanni Diacono, Istoria Veneticorum (= Fonti per la Storia dell'Italia medievale. Storici italiani dal Cinquecento al Millecinquecento ad uso delle scuole, 2), Zanichelli, Bologna 1999 ( text edition based on Berto in the Archivio della Latinità Italiana del Medioevo (ALIM) from the University of Siena).

- Ester Pastorello (Ed.): Andrea Dandolo, Chronica per extensum descripta aa. 460-1280 dC , (= Rerum Italicarum Scriptores XII, 1), Nicola Zanichelli, Bologna 1938, pp. 161-163. ( Digital copy, p. 160 f. )

- Șerban V. Marin (Ed.): Gian Giacomo Caroldo. Istorii Veneţiene , Vol. I: De la originile Cetăţii la moartea dogelui Giacopo Tiepolo (1249) , Arhivele Naţionale ale României, Bucharest 2008, pp. 62–64, especially 65 f .: After Caroldo, the Doge did not refuse to return to office but returned to office for six months and four days, "acquietati gli publici rumori, persuase al Popolo l'elettione d'un novo Duce" .

Legislative sources, letters

- Roberto Cessi (Ed.): Documenti relativi alla storia di Venezia anteriori al Mille , 2 vol., Vol. II, Padua 1942, pp. 7, 10, 13 f., 16-21.

- Capitularia regum Francorum ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , Legum sectio II , II), ed .: Alfred Boretius , Victor Krause , Hanover 1897, p. 138 ( digitized by Pactum Karoli III from January 11, 880 ).

- Karoli III Diplomata ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , Diplomata regum Germaniae ex stirpe Karolinorum , II), Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin 1937, n. 17, pp. 26–31 (“Karl renews the contract with the Venetians for Doge Ursus. Ravenna 880 January 11 “, The text can be found in the Codex Trevisanus of the 15th century, f. 54, in the Venice State Archives ). ( Digitized version of the MGH edition )

literature

- Marco Pozza: Particiaco, Orso I. In: Raffaele Romanelli (Ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 81: Pansini – Pazienza. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2014, (forms the basis of the presentation part).

Remarks

- ^ Alvise Zorzi : La repubblica del leone. Storia di Venezia , Bompiani, 2008.

- ↑ La cronaca veneziana del diacono Giovanni , in: Giovanni Monticolo (ed.): Cronache veneziane antichissime (= Fonti per la storia d'Italia [Medio Evo], IX), Rome 1890, pp. 59–171, here: p. 128 ( digitized .

- ↑ La cronaca veneziana del diacono Giovanni , in: Giovanni Monticolo (ed.): Cronache veneziane antichissime (= Fonti per la storia d'Italia [Medio Evo], IX), Rome 1890, p. 129, note 2.

- ^ Roberto Pesce (Ed.): Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo. Origini - 1362 , Centro di Studi Medievali e Rinascimentali "Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna", Venice 2010, p. 39.

- ↑ Pietro Marcello : Vite de'prencipi di Vinegia in the translation of Lodovico Domenichi, Marcolini, 1558, p. 26 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Șerban V. Marin (Ed.): Gian Giacomo Caroldo. Istorii Veneţiene , vol. I: De la originile Cetăţii la moartea dogelui Giacopo Tiepolo (1249) , Arhivele Naţionale ale României, Bucharest 2008, p. 64 f. ( online ).

- ↑ Heinrich Kellner : Chronica that is Warhaffte actual and short description, all life in Venice , Frankfurt 1574, p. 10r – 10v ( digitized, p. 10r ).

- ↑ Alessandro Maria Vianoli : Der Venetianischen Hertsehen Leben / Government, und dieback / From the First Paulutio Anafesto to / bit on the now-ruling Marcum Antonium Justiniani , Nuremberg 1686, pp. 107-111, translation ( digitized ).

- ↑ Jacob von Sandrart : Kurtze and increased description of the origin / recording / areas / and government of the world famous Republick Venice , Nuremberg 1687, p. 20 f. ( Digital copy, p. 20 ).

- ↑ Johann Friedrich LeBret : State history of the Republic of Venice, from its origin to our times, in which the text of the abbot L'Augier is the basis, but its errors are corrected, the incidents are presented in a certain and from real sources, and after a Ordered in the correct time order, at the same time new additions, from the spirit of the Venetian laws, and secular and ecclesiastical affairs, from the internal state constitution, its systematic changes and the development of the aristocratic government from one century to another , 4 vols., Johann Friedrich Hartknoch , Riga and Leipzig 1769–1777, Vol. 1, Leipzig and Riga 1769, pp. 176–179 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Samuele Romanin : Storia documentata di Venezia , 10 vols., Pietro Naratovich, Venice 1853–1861 (2nd edition 1912–1921, reprint Venice 1972), vol. 1, Venice 1853, pp. 199–204 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ August Friedrich Gfrörer : History of Venice from its foundation to the year 1084. Edited from his estate, supplemented and continued by Dr. JB Weiß , Graz 1872, pp. 208-218 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Pietro Pinton: La storia di Venezia di AF Gfrörer , in: Archivio Veneto 25.2 (1883) 288-313, here: pp. 295-298 (part 2) ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Francesco Zanotto: Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia , Vol. 4, Venice 1861, p. 37 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ^ Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna : Storia dei Dogi di Venezia , Vol. 1, Venice 1867, o. P.

- ^ Heinrich Kretschmayr : History of Venice , 3 vol., Vol. 1, Gotha 1905, p. 100 f.

- ^ John Julius Norwich : A History of Venice , Penguin, London 2003.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Orso I. Particiaco |

Doge of Venice 881–887 |

Pietro I. Candiano |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Particiaco, Giovanni II. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Participazio, Giovanni II. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | 15. Doge of Venice |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 9th century |

| DATE OF DEATH | at 887 |