Orso Ipato

Orso Ipato (* in Eraclea ; † 737 ?), In the contemporary sources Ursus , sometimes also called Orleo , was Doge of Venice from about 726 until his death . According to the Venetian tradition, as the state-controlled historiography in Venice is called, he is the third doge. But more recent work see him as the first real Doge. According to Venetian tradition from the middle of the 14th century, a fleet under him recaptured the Eastern Roman-Byzantine Ravenna from the Lombards , which was the first time that Venice intervened militarily outside its territory and acquired trading privileges. Ultimately, Ursus was killed in the course of fighting within the Venetian lagoon , but the arguments behind them cannot be classified with any degree of certainty in the larger political context. Ursus was followed by five Magistri militum , who ruled for one year each, including his son Deodatus , who was Doge from 742 to 755. His immediate successor as ruler of Venice was Dominicus Leo .

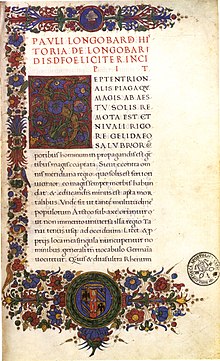

As far as we know today, the reconquest of Ravenna did not take place until two years after Ursus' presumed death date, namely in the autumn of 739. This already suggested the sequence of the events described in the next source, the Lombard story of Paul the deacon from the late 8th century . Yet the dating of this event has been debated for more than a century.

Surname

Ursus or Orso (the Bear ') received, the end of the 19th century undisputed representation, as a reward for the recapture of Ravenna, under the Lombards Hildeprand had occupied the Byzantine emperor the honorary title ipato Greek (: ὕπατος, or . hypatos, Latin: consul). Later chroniclers and historians understood this title as his proper name.

Francesco Sansovino mentions in 1587 in his work Delle cose notabili della città di Venetia as an alternative name to “Orso” also “Orleo”, a name variant that Girolamo Bardi also mentions in 1581 in his Chronologia universale . Jacob von Sandrart calls the doge in his 1687 published Opus Kurtze and an increased description of the origin / recording / areas / and government of the world-famous republic of Venice "Horleus Ursus Hypatus".

Core events according to the Venetian tradition

After the death of his (alleged) predecessor Tegallianus , who in the early sources is only mentioned as Magister militum , not as Doge, Ursus was elected Doge by acclamation . Like his two predecessors, Ursus came from Eraclea . His reign fell into a troubled phase, because in Italy the effects of the Byzantine iconoclasm were felt, which by a decree of Emperor Leo III. had been triggered. The Italian territories defended themselves against the destruction of the images, which had already begun by the Emperor in Constantinople. A letter from Pope Gregory II from around 730 indicates the expulsion of the Eastern Roman magistrates, as well as the establishment of their own. A direct reference to the Venice lagoon cannot be proven with this general statement.

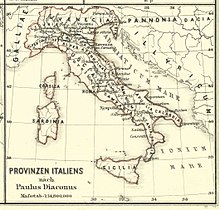

During this time of theological disputes that spread across society, pirate fleets of the Muslim conquerors known as Saracens also appeared on the coasts of northern Italy and Dalmatia . In addition, a new phase of Lombard expansion began in mainland Italy under King Liutprand (712-744), whose intention was to conquer the Eastern Roman territories including Rome and Ravenna. Liutprand allied himself with the Frankish caretaker Karl Martell , whom he supported against the Saracens advancing from the Iberian peninsula . This in turn prevented the Franks from supporting the Pope, because the Pope was at war with Liutprand.

In 728, one year after taking office, the Longobard king is said to have invaded the Byzantine area around Ravenna. Accordingly, he conquered the city and expelled the resident imperial exarch . This fled to the Venetian lagoon . At an unspecified point in time, the Venetians, at the request of the Pope, sent their navy under the leadership of Ursus, drove out the invaders and reinstated the Byzantine exarch - however, this event has now been dated to around 739/740 (see below) .

Orso was murdered in 737 when he interfered too one-sidedly in a long-standing dispute within the lagoon in favor of his native city, or simply because he was considered too haughty. His son Deodatus was expelled from Venice, but was soon brought back and made magister militum for a year or two . Eventually he was later elected Doge himself. After Ursus and before Deodatus, Venice was ruled for five years by magistri militum , which changed every year .

Reception and embedding in historiography

Paulus Diaconus writes in his Historia Langobardorum that after the death of dux Marcellus , who ruled “apud Civitatem novam Venecie ducatum” for 18 years and 20 days, “Ursus dux” followed, who ruled for 11 years and 5 months ('rexerat '). Paul also provided the epic images that appeared again and again in later descriptions, for example when he was told by Emperor Leo III. reports how he forced all residents of the imperial capital to burn all the images of the Savior, his mother and all the saints in the middle of the city in fire (VI, 49).

From Paulus Diaconus to Andrea Dandolo

Since some of the most influential families in Venice saw themselves as descendants of Orso or of his constituents, the representation of the events down to the finest ramifications of the choice of words in the context of the state-controlled historiography from the middle of the 14th century was of great importance. The chronicle of Doge Andrea Dandolo largely displaced the stock of tradition , which not only bundled the legends and myths from the early days of Venice, but also permanently added them to the basis of the development of Venetian myths. In it developed a historiography controlled by the state leadership, which was adhered to until 1797. As a result, most of the works from the time before Andrea Dandolo disappeared, as Marco Foscarini discovered in 1732. On the other hand, the chronicle, which was written between 1342 and at least 1352, gave historiography a strong impetus. She cited at least 280 documents in full or in regesta form , a work that could only be done with direct access to the archives in the Doge's Palace. At the center of these efforts were the Chancellors Benintendi de 'Ravignani (Grand Chancellor from 1352) and Raffaino de' Caresini , the former a friend of the Doge, the latter the continuation of the Chronica Brevis for the years 1343 to 1388, which is also ascribed to the Doge.

In Dandolo's work, the doges appear almost as the only masters in history, while the institutions of the people's assembly (arengo) or the tribunate, which were extremely influential in Ursus's time, were reinterpreted or almost forgotten. Depending on the point of view, the "rabble" or the "people" acted for the later authors. Moral questions or those of legitimacy, but also analogies to one's own epoch, mixed with speculations that were not thought through critically, prevailed, which is hardly surprising in view of the extensive lack of understanding for earlier constitutional states, but especially the poor tradition. In addition to the question of dating, later historians dealt with the relationship to the Pope and Byzantium in the context of the iconoclastic controversy, the question of the first tangible marine expansion, at the center of which was the conquest of Ravenna, and the early trade privileges closely related to the return of the city by Byzantium, but also the spatial and political internal structures in the lagoon. In literary terms, around 1800, on the basis of notions of Orso's "presumption" that had already been solidified by constant retelling, the question of tyrannicide was even brought up on the stage using the example of his murder.

Many authors consistently regarded the iconoclasm as the supreme guideline for action by the popes, to which all political thinking was allegedly subordinated. In order to prove this, however, the sequence of events, and therefore the entire chronology, in particular the battles for Ravenna, had to be adjusted. Paulus Diaconus describes in his Lombard story (VI, 54), after he reports of the successful alliance between Liutprand and Karl Martell (739), how the regis nepus , the nephew of the Lombard king, had to put up with the humiliating expulsion from Ravenna, which had just been conquered he was also captured by the Venetians. This report appeared in the 10th century by Johannes Diaconus , who apparently had insight into a letter from Pope Gregory III. to Antoninus, who had taken Patriarch of Grado . In this letter, the Pope asked for help in recovering Ravenna for the Emperors Leo and Constantine. Johannes reproduced the wording of the letter, but without date and place, at least placed it in the days of the Magister militum Julianus Hypathus , which, according to traditional Venetian chronology, corresponded to the time around 740. The aforementioned Doge Andrea Dandolo delivered a very similar report in the middle of the 14th century, who in turn invokes Paulus Diaconus, because the courage and faith of the Venetians are proven by “testimonio Pauli gestorum Langobardorum ystoriographi”. But the addressee of the papal letter quoted by Dandolo was now Dux Ursus , which placed the letter between about 727 and 736. Not only did he move the battle for Ravenna more than a decade ago, but he also confused Pope Gregory III. (731–741) with Gregory II. (715–731), which means that the fighting took place between 727 and the beginning of 731. This is the most cited date for fighting until recently.

From the 14th century to the end of the republic (1797)

The historiography, which was largely based on the work of Doge Andrea Dandolo , saw the battle for Ravenna as central against the background of the iconoclastic controversy and the "national resistance" of the Italians against Byzantine rule. This made a turning point in history from the use of the fleet under the leadership of the Doge. On the one hand, Venice could be singled out as the savior of Byzantium (which Venice poorly thanked for the return of Ravenna) and at the same time the Pope. On the other hand, the city received economic privileges and rule over the Adriatic for the first time in the Byzantine Empire. Venetian historiography was also able to show that the paths of supremacy of the Serenissima that were taken later went very far back, but also that only internal disputes could stop Venice, those disputes that had led to Ursus' death.

The oldest vernacular chronicle, the Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo , presents the events that are obviously not (no longer) understandable even for historians on a largely personal level. Ursus, the "fu elevado Duxe", also came from, like his predecessors, from Eraclea. From the "imperial maestade fu molto honorado passando per le soe contrade". What is meant is the Byzantine emperor, who traveled through the lagoon cities (this is how the editor interprets it) and honored the doge with high honors. On this occasion he told Ursus “constituido signor gieneral de tuta la soa provincia” (p. 15). The chronicler thus assumes that there was a formal act of installation by the emperor in his presence. Ursus wanted to dominate the "habitanti de Exolo" in everything that led to great tension, then to open struggle. They wanted to defend themselves “virilmente”, whereby a battle ensued in the said “Canal d'Arco”, after which all their lost brothers, sons and other relatives (“che qual ne havea perso fradeli, qual fioli, qual altro parente ") mourned. When Ursus was preparing for a second battle, the remaining Eraclians allied themselves - that is probably how “cum alcune spalle” is understood - with Magistri militum . After the death of Ursus, they moved to the new administrative center of Malamocco. When it came to perfect peace (“reducti ad perfecta paxe”) they appointed an annually changing magister to rule (“se deliberono far un rector et cavo tra loro, el qual si dovesse mudar ogni anno”).

Pietro Marcello meant in 1502 in his work later translated into Volgare under the title Vite de'prencipi di Vinegia , "Orso Ipato Doge III." "Fu creato Prencipe l'anno DCCXXVI" ('was made prince in 726'). Under him, Ravenna was occupied by the Lombards, so that its exarch turned to the Venetians for help. The Pope also asked them to take up arms and help the exarch against the "insolentissimi Barbari". 'In order to show obedience to the Pope' (“per ubidire al Papa”) they sent a large fleet to Ravenna, which they immediately conquered and immediately returned to the exarch. With that, everything is said for Marcello, and he immediately moves on to "Calisto Patriarca d'Aquilegia", who attacked Grado and triggered a war that brought the Republic to Marcello into great disorder ("turbò grandemente lo stato della Rep.") . It is believed that this was due to the "insolatissima natura di questo Doge". This choice of words rhetorically put the “Barbari” and the Doge on the same level, because it combined the aforementioned “insolentia” or “insolence”. The Iesolani no longer wanted to endure the “alterezza” and the “superbia” of the Doge (“sopportare”) and took up arms. The “superbissimo doge”, the “extremely presumptuous doge”, wanted revenge and also took up arms. But the fierce fighting was ultimately fruitless, and 'his popolars' tore the Doge, whom they blamed for the war, to pieces after eleven years in office. Since the Venetians did not like electing a new doge, they “created a“ maestro de 'soldati ”in the republic, whereupon the author enumerated the five magistri militum who now ruled the lagoon from Malamocco for a year .

Also for the Frankfurt lawyer Heinrich Kellner , who in his Chronica das ist Warhaffte actual and short description, all life in Venice , which was published in 1574, refers strongly to Marcello, but at the same time made the Venetian history better known in the German-speaking area, "Orsus Ipatus" became 726 elected “Hertzog”. Kellner apparently misunderstood the word "Esarco" and believes the Exarch is a proper name. This "Esarcus" asked for help in Venice, which agreed to retake Ravenna. The Venetians did this because the Pope “admonished them” to wage war against the “hard-working Barbaros”. The Patriarch of Aquileia , "Calixtus", attacked the Grado area, but soon stopped the war. After that, an “internal or civil war” shattered “the Hertzogthumb”, because “the Jesulans announced that they could no longer endure their arrogance and unsteadiness”. Then Orsus started a war "out of vindictiveness". In the eleventh year of his duchy he was "hewn to pieces / by his own people / then they were responsible for all the causes of the war." For the next few years the Venetians, who were no longer interested in a doge, chose a "war colonel" . The first of them, "Dominicus Leo" was elected unanimously. Kellner only sees the murderous struggle between the "Eraclians and Jesulans" at the end of the rule of the Magistri militum , including a battle in the Canal Arco. The population left "Eracliam / Jesulam und Equiliam" and the residents "moved elsewhere". After that "the place came back under the regiment of the Hertzians".

According to the brief description in the Historie venete dal principio della città fino all'anno 1382 by Gian Giacomo Caroldo , which he completed in 1532, "Orso" was elected Doge in 726 "con universal consenso". After Caroldo he was "nobile et habitatore di Heraclea". The only event that he mentions is the battle for Ravenna (which, according to current knowledge, he puts in the wrong timing). The Longobard king Liutprand had Ravenna besieged, whereby "Capitano di quella impresa era Ildebrando nepote della Maestà Sua". So the nephew of the Lombard king was in command of this enterprise. Together with “Peredeo Duca Vicentino” he destroyed the army of Ravenna and in the end the city came under the rule of the Longobards (“venne sotto il dominio de Longobardi”). In order to escape the anger of the barbarians (“per fuggir il furor de Barbari”), the Exarch went to “Venetia”, “like a safe haven”. Pope Gregory wrote a “breve” to “Orso Duce”. Basically he wrote: Bishop Gregory, Servant of the Servants of God, to his beloved son Orso Duca de Venetia. Because the city of Ravenna, which was the head of all others, was taken by the unworthy Lombards, and our excellent son, the Lord Exarch, is staying with you (as we have learned), your "Nobiltà" should share the city with him bring back under the rule of the Lords and Our Sons Leo and Constantine. With religious zeal, the Doge prepared a fleet of strong forces and attacked Ravenna. "Ildebrando" was captured while "Peredeo" was killed. The exarch was reinstated. The “virtuoso operationi” of the “Duce Veneto” in honor of the Catholic faith were celebrated with the testimony of the “Paulo historico Longobardo”, as Caroldo also notes. In contrast to Marcello, Caroldo emphasizes extremely strongly the struggle for Ravenna and the attitude of the Venetians to it, while he hardly devotes a line to the internal struggles that, according to Marcello, led to the doge's fatal death. He neither names the antagonists, nor does he even mention fights, but only suggests the “discordia” of the time, the “discord”. As happens to many "grandi Signori", the doge was badly recognized for his rare deeds, and so after 11 years and 5 months as a doge, he was badly dead due to "discord" between the "Veneti Cittadini" come (“fù malamente morto”).

Bernardo Giustiniani, who in his Historia, printed in 1545, reproduces the speech of the exarch, who fled the Lombards from Ravenna before the people's assembly in Venice (S. CXLI - CXLIIII), closes with the words: "Tutto il consiglio fu del parere del Doge Orso", the people's assembly was therefore “unanimous in the opinion of the Doge”. He also knows how to report the exact strength of the fleet. According to this, 80 ships, 20 of them large, headed for Ravenna, pretending to support the emperor against the Saracens (S. CXLIIII). The masts of the large ships were, according to the author, so high that the besiegers could overcome the city walls. Giustiniani also explicitly refers to the Historia of the Longobard " Paolo Diacono " (CXLV) in this description . But he constructs a completely different context by drawing together events that are relatively far apart in time. Emperor Leo, "huomo di nessuna virtu, ma ben di notabile perfidia, & avaritia" ('man without any virtue, but of remarkable slyness and greed'), according to the author, continued to try, as Giustiniani writes, to ruin the empire. Because after the two-year siege of Constantinople by the Saracens (717–718), in which, according to Giustiniani, two times 300,000 people were killed, the emperor plundered the churches. When the Pope resisted the destruction of the pictures, the Emperor tried to have him murdered. In Ravenna, where Orso was still with the fleet that had conquered the city, there were also riots. According to Giustiniani, views emerged in Orso's camp, such as the one that the emperor was “peggiore di tutti i barbari, & di Macometto anchora”, that the emperor was worse than the barbarians, by which the Lombards were probably meant, and even worse than him Prophet Mohammed . So the Christians needed a new emperor, some thought of Karl Martell , the Frankish king (CXLVI f.). But the Pope preferred to advertise his cause with letters to all potentates. The Venetians brought the relics of the iconoclastic martyrs to their churches, such as St. Theodore to San Giorgio Maggiore (who became the patron saint of Venice). An assembly of bishops excommunicated the emperor. But then “Heraclia” and “Equilo” fought over the borders for two years, fought a “grandissima battaglia” in the “canale hoggidi chiamato del larco”, so they fought an extremely big battle in the Arco Canal until both cities were almost ruined (see CLI). As the "authore" of all inner Venetian evils, Orso was killed in a tumult (CXLVIII). Giustiniani's evaluations have been upheld for a long time, especially with regard to the iconoclasm and Leo's role in it, but are now considered refuted. The admirers of images , whose sources have been handed down, got too much on the person of the emperor; at the same time, they exaggerated the radical nature of the destruction.

The chronological classification of the first secured doge, according to the state-sponsored creation of legends, but the third doge, was extremely problematic. As with his predecessors, Ursus' information about his reign differed greatly for a long time. Marco Guazzo states in his cronica in 1553 that "Orso Ipato terzo doge di Venezia" was made Doge in 721. After that he was in office for nine years, that is until 730. The author considered him “huomo di mala natura”, and he had also driven the Heraclians into armed struggle. The few survivors would eventually have turned against 'the man of bad nature' and killed him. After that, Venice was without a doge for six years (from 730 to 736) "reggendosi per altri magistrati, & uffici". The lagoon ruled itself through other magistrates and offices, which probably meant the magistri militum , which ruled for a year . An independence from the Eastern Roman-Byzantine Empire is implicitly suggested here.

Francesco Sansovino , however, wrote in his Cronologia del mondo in 1580 under the year 726 (thus classifying the beginning of his rule): "O rso Ipato, cioè Cōsolo imperiale" ... "è morto dal popolo", 'Orso Ipato, so imperial consul', is so killed by the people. Only after five years did they return to the Dogat by making their son Deodato a Doge. In his Sommario istorico in 1609, however, Michele Zappullo set the election year to 724 and the year of death to 729. In 1630, the election mode again mentions the year 726 for Orso as the election year, plus a reign of eleven years and five months, i.e. up to around 737.

In Alessandro Maria Vianoli's Historia Veneta from 1680 (Volume 1), which appeared six years later in German, “Orsus Ipatus the Third Hertzog.” Sabellico, according to Vianoli, “one of the very ancient Venetian historians”, calls him “Orleo” ( P. 36). He also pulled his constituents into "all kinds of hard work." He had "also practiced and exercised the youth almost every day in the weapons of war in use at the time / as much on the water as on land /". After “the Lombard king” had taken Ravenna, and “Esarcus, who at that time ruled the same / in the name of the emperor / fled Venice / called the Hertzog for Hülff / meanwhile also a pleading and pathetic letter to him from Pope Gregorio II. arrived ”to retake Ravenna. Although he was in an alliance with Liutprand, he obeyed the Pope and wanted to defend "the Esarcum" at the same time. The "Armada" "/ that bit in 80th warships" conquered the city "with the help of the night" (p. 37). The victory was all the greater "because Perendius remained dead in it / and Ildebrand was taken prisoner to Constantinople". After the town was handed back to "Esarcus", there was a dispute between Grado and Aquileia because "Calixtus, the patriarch of Aquileia, took away two islands / named Centinara and Massone". However, under papal pressure and in view of the Doge's armor, he had to surrender it. Soon there was such a disagreement, “that it seemed / as if she wanted to turn the whole / and at that time still very weakly founded state completely from the bottom to the top / sintemmal the Eracleans, because of the Grentz divorce / into the two years / one hard war / with the Jesolans, waged ”. And "while the Hertzog / against the will of the subjects / intended to continue the war ... he is once on the square / because he want to accept even more people / seized by them / and / after an eleven year and five monthly heroic and heroic government Pieces were chopped up ”(p. 39 f.)“ Kurtz after his death ”, adds Vianoli,“ the regiment of the city was changed / sintemalen the whole community bore a great disgust / in Eraclea, as in a shameful murder pit / added together get. Because of this / with the greatest unanimity / the entire island of Malamocco ", where" finally no longer any more centers / but in the same position Maestri di Cavalieri, or Rittmeister / who had to remain in such office for only one year / to be chosen / has been decided ". Vianoli expressly states that the first of these magistri militum was elected unanimously (p. 41). Vianoli states that there is a direct connection between the Doge's fall and the subsequent move to Malamocco.

But the uncertainty among the chroniclers was much greater than suggested by the comparatively close dates. In 1687 Jacob von Sandrart wrote in his work Kurtze and increased description of the origin / recording / areas / and government of the world-famous Venice Republic that "Horleus Ursus Hypatus" 726 had been "chosen". But he adds: The Doge “drove away the Exarchum at Ravenna, but became so dominant / that the people revolted against him in the eleventh year of his reign / and killed him. This is set by others in the 680th year. ”This uncertainty in the dating - and in the question of who was actually expelled - continued. In Volume 23 of the source series Rerum Italicarum Scriptores edited by Lodovico Antonio Muratori it is reported that Orso was elected in 711. After describing the battle for Ravenna, the author refers to the taxes that the Doge "Gesulo" wanted to impose and how the civil war then came about. He also mentions the two-day naval battle in the Canal d'Arco, the later Canal Aquiliana, but he doesn’t mention the iconoclastic controversy.

Apparently from the late 18th century, although no new source emerged, the assumption that Orso had ruled from 726 onwards was finally consensus. Even Samuel von Pufendorf (1632-1694), who calls the Doge "Ursus Ippatus", mentions the years 726 and 737 as the beginning and end of his reign.

But not only about the government data has been speculated over and over again for centuries. The origin of the family, to which a number of noble families in Venice can be traced back, was also unclear. Pietro Antonio Pacifico added in 1751 in the first volume of his Cronaca veneta sacra e profana , 'some wanted' that the Doge's family should be relocated from Dalmatia to Eraclea, which he also called 'Alt Malamocco' ('Malamocco vecchio'). But 'others' claimed that Orso's family were originally from Padua . Pacifico itself remains neutral on this issue. The Doge fought against the Lombards and, as the author adds, a Greek fleet was destroyed, “Ildebrando, Nipote del Re” captured, “Daredo, Duca di Vicenza” killed. But two years and two months after he saved the republic, Orso was murdered.

In the same year as Pacifico, Gianfrancesco Pivati published the 10th volume of his Nuovo dizionario scientifico e curioso sacro-profano . The year 726 is also certain for him, the two places of origin Dalmatia and Padua are only 'claimed' by many. The choice of words in which the author describes the processes succinctly and in a very similar way seems almost standardized.

But the slow process of legend formation was by no means over. Augustinus Valiero claimed in 1787 that Orso had won the Venetian youth for the fleet, similar to Vianoli, so that within a few years not only the pirates could be defeated, but also the Greek fleet, and that the Venetian naval forces succeeded in conquering Ravenna. The Exarch Paul had convinced Venice of the danger of the Lombards and of their deceit, and the Pope had also urged a counter-attack against the barbarians. This is how Ravenna was retaken. However, when an envoy of the emperor demanded the destruction of the images in the churches of the lagoon, the Doge referred to the conquest and return of Ravenna and the constant support of Constantinople in the fight against the Lombards, adding that in matters of the church the Venetians exclusively to the Pope would follow.

Orso was later accused of advocating Eraclea too unilaterally, with the result that the Doge was murdered in the course of the fighting after he had served in his post for eleven years and five months. Although he had shown great spirit and courage, according to Augustine Valiero, he was haughty and inclined to tyranny. Vincentius Briemle formulated this idea more drastically in his pilgrimage in 1727 : According to him it was the case that Ursus, "inflated by pride and arrogance, began to tyrannize tremendously, so the Pövel stood up against him and beat him to death in 737." Knapper , but with the same intention Ferdinand Ludwig von Bressler and Aschenburg had already formulated in 1699: “Ursus Hypatus misused this ducal power / therefore the people A.737. murdered ".

For Johann Friedrich LeBret , "Ursus" was the third doge, "whom some also call Orleo". According to LeBret, he had "a lively and enterprising spirit, and loved war". “Because of this, some call him Orleo Hypato, Orsus the Great”, a claim made by François Combefis (1605–1679), which LeBret does not believe (p. 96, note 8). Conventionally, the doge played a decisive role in the “reconquest of Ravenna” (the author offers the years 728 and 730 in marginalia). He believes that the city will be split into two parties, one that is friendly to images and one that is hostile to images. After the exarch "Paul" was murdered, the Longobard king had moved to the city. The author takes a highly critical view of the tradition since Andrea Dandolo: “Dandulus is sending a letter through which this Pope [Gregory II] is said to have exhorted the Venetians to recapture Ravenna. But we are not inclined to honor the Venetians by quoting this letter ”. At the same time, in a footnote, he also rejects the Sagornina , i.e. the chronicle of Johannes Diaconus, at this point, because he has "but otherwise all the marks that he has been placed under". In addition, the letter from Johannes was not addressed to the Doge, but to "the Patriarch of Grado, Antonius". Nevertheless, De Monachis - meaning Lorenzo De Monachis (1351–1428) - reported “that the Pope had asked the Venetians to wrest Ravenna from the hands of the enemy.” According to LeBret, the Venetians saw subordination to the naval power of Byzantium as more advantageous on. Therefore " Eutychius ", the exarch who fled into the lagoon, found "an inclined ear", especially since "this was a weyde for his warlike spirit". "Hildebrand, a nephew of the Luitprand, who presumably commanded the besieged city, was captured and taken to Veneto." Incidentally, the author mentions that the Archbishop of Ravenna, Johannes, had also fled into the lagoon, "Peredeus, Duke of Vicenza ... was killed in the battle ”. But in Venice there was resistance to Ursus: "One was not satisfied with his warlike ventures, which had cost the state too much". The "Equiliner" stood out, "these uneducated Venetians". The risk of an act of revenge Liutprand was also reduced by his constant distraction by other scenes, especially since he had surprisingly agreed with Eutychius to go against the dukes of Benevento and Spoleto. The author introduces the doge murder succinctly with the words: “There are people for whom it is a misfortune when they are happy.” Ursus' “imperial mine” after this success made him hated. The war-induced climbers supported him, the others hated his despotic spirit. The “belligerent Ursus would rather see the state disrupted than allow its violence to be restricted… Perhaps he hoped to maintain sole rule under these disruptions. But the exuberant mob, which presumably had some great leaders as leaders, got the upper hand, penetrated into his house and sacrificed it to liberty. "Only Venice has sacrificed so many of its" princes ". "He had ruled for eleven years and six months." For LeBret, the epithet was an expression of the "consular dignity with which the Greek emperors usually adorned those who had distinguished themselves to their advantage."

French Revolution, Risorgimento

With the French Revolution and the execution of the king, another aspect moved to the center of reception history, namely the question of tyrannicide . Giovanni Pindemonte (1751-1812) wrote a Jacobean drama entitled Orso Ipato within a few days , which was performed on September 11, 1797 in the Venetian City Theater. The play had a surprising success. Orso is a liar, villain and opportunist, driven by lust for power and full of contempt for the people. His father-in-law Obelario, fighter for popular sovereignty and enemy of all tyranny, takes the side of the people of Eraclea, who were oppressed by Orso. The young Eufrasia, daughter of the Obelario and Orso's wife, appears as a vain mediator. In the end, both men die during the uprising against tyranny, an uprising that was brought onto the stage in the first crowd scenes.

The following year Carlo Antonio Marin brought out the first volume of his Storia civile e politica del commercio de 'veniziani . For him, the Venetians under Orso made the experience for the first time that they could not only defend their islands and trade under the suzerainty of the emperor, but that they were also able to wage war with their fleet outside of their territory. Marin refers to Bernardo Giustiniano when he explains that Orso set up schools to accustom young men to the demands of naval warfare. But he did not have access to the chronicles that Giustiniano certainly quoted in order to be able to prove this. For the siege of Ravenna - Marin explicitly assumes the intention to make a profit, without which the Venetians would not have jeopardized their freedom - 60 ships were equipped with him. In order to keep the Lombards in the dark about their intentions, they faked a campaign against the Saracens . After the conquest, Marin believes that the Venetians were the economic masters of the Adriatic, Ravenna and the East, and he was 'sure' that the Exarch would have paid for the war costs, that the Venetians were allowed to set up trading houses and that they were given preferential treatment with taxes .

For Antonio Quadri , Orso, who, as is now common practice from 726 onwards, was courageous and experienced in weapons (“coraggioso e armigero”), as he wrote in his Otto giorni a Venezia of 1824. After great successes against pirates, the assertion of rule over Dalmatia and the Slavs , the victory over the Lombards in the battle for Ravenna, the emperor said he was awarded the title of Ipato . However, this all led to hatred and factioning, then to fights in the course of which the Doge was killed. The minds were so 'whipped up' (“esasperato”) that the “nazione”, instead of electing a new doge, resorted to the Magistri militum . Marin had considered this to be a clever move by the people's assembly to end the anarchy, because it gave power to a single Magister militum , if only for one year at a time.

Even Jacopo Filiasi (1750-1829) had 1812 in his storiche Memorie de 'Veneti a broader representation of trying to fill the nearly 30 pages. Filiasi referred much more strongly to the older sources, above all to the chronicle of Doge Andrea Dandolo from the middle of the 14th century. The author also included the political environment, which was determined by the iconoclasm of the East, against which all “Itali” resisted, and against which Venice rose up. After a failed assassination attempt on the Pope, the emperor tried violence, but the Venetians resisted. There is even talk of a counter-emperor who they wanted to bring to Constantinople , an alleged undertaking that the Pope is said to have prevented the Venetians from doing. As Filiasi notes, however, the Venetian sources are in the dark if they make any hints. Emperor Leo managed to build a pro-Byzantine party that plunged Ravenna into violent discord (“pazza discordia”), an opportunity the Lombards used to conquer the city. After Filiasi, the new exarch Eutychios fled to Venice and placed himself under the protection of Orsos, under whose leadership Ravenna was recaptured. Filiasi believed that the danger of becoming 'the prey of the barbarians' should have been enough to agree, but that 'only the people advance in good faith, but the leaders have completely different goals' - and in the end only these advantages would result the fights. The emperor, who still wanted to enforce iconoclasm against the resistance of the Pope, tried several times to conquer Ravenna, but in the end Venice defeated his fleet in front of the city. Filiasi, who, in addition to general reasons such as the character of the Italians, cites that although the disputes were calmed down under the “Numa” of Venice - Marcellus, to whom the legend awarded the rank of Doge - they were calmed down under Ursus broke loose again. He had acted too harshly on the Equilians, had even demanded a tribute from them, and there was fighting that turned into a civil war, as Dandolo had already noted, whom Filiasi quotes ("Civilibus bellis exortis, nequiter occisus est"), but without indicate the exact reference. Filiasi suspects that the people may also have revolted against absolute rule by the Doge, and that the office was abolished for this reason.

For the author of a brief booklet that lists the fourteen forms of rule and their protagonists in the revolutionary year of 1848, which have shaped the history of the city since the legendary founding of Venice in 421 up to the 'dictatorship of Manin' in 1848 and up to the 'Decemvirato' only the internal quarrel ("zuffa") and the possible connection with the Byzantine emperor were significant enough to be mentioned. For the anonymous, the form of rule was a “Repubblica democratica”, represented by the doge and by “notables”.

Giovanni Bellomo, on the other hand, considered Orso's battle for Ravenna in his anecdotal representation of the Middle Ages for a wide audience, his Lezioni di storia del medio evo , so important that it found its way into his work published in 1852. For him, Orso was 'filled with warlike spirits' (“pieno di spiriti marziali”). He confidently dated the surprise attack on Ravenna to 729, and he also knew that the fleet comprised 80 ships. Like his predecessors, he mentions the honor of the consul title that Leo III gave him. transferred, but he emphasizes its reward character for the recovery of Ravenna. He also mentions the fight between Eraclea and 'Equilio or Giesolo'; He also explains in a footnote that it was " Cavallino ", which at the time was located between the port on the Piave and that of Tre Porti. For these reasons, the Venetians, instead of installing a new doge, created a new magistrate, the “Mastromiliti”.

In his ten-volume opus Storia documentata di Venezia, Samuele Romanin devoted a great deal of attention to the events . The enormous historical work is about 4000 pages long, and Orso Ipato fills pages 109 to 115 in Volume 1.However, Romanin's starting point was exactly what most other historians of his time left out, namely the iconoclast and the role of Kaiser and Pope. He reports of attempts to assassinate the Pope, of the role of the Lombard king, who in his eyes is above all glorious, of the arrogance of the emperor, only to pause and admit that the tradition is contradictory, confused, 'confused' ("imbrogliato"), that the historians had also worked 'poorly' and 'negligently', which made it very difficult and sometimes even impossible to reconstruct the processes. So Romanin can for example the contradicting actions of the Pope, who allied himself with the Lombards and excommunicated the exarchs, but still campaigned for the reconquest of Ravenna, who tried Leo III. convincing with letters and at the same time discrediting the Lombards, hardly reconciling them in the context of his moral historiography. He dates the conquest of Ravenna to the time from 727 to the beginning of 728, reports of the battles between the allies and opponents of the emperor in Ravenna, of the death of exarch Paul and his replacement by Eutyches in 728. Gregory succeeded, according to Romanin, with mere words to keep the exarchs and the Lombards from conquering Rome. Towards the end, and almost only in passing, the author describes the dispute between the most important lagoon cities and mentions succinctly that Orso was 'cruelly murdered' (“crudelmente assassinato”).

More closely tied to historiographical conventions, Francesco Zanotto wrote in his work Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia of 1861. For him, the doge was “uomo di acuto ingegno e di nobil prosapia”, a “man of keen understanding and of noble clan” who defended himself understood the craft of war and taught 'the Venetian youth' how to handle weapons. The starting point of the upheavals was also with him the iconoclasm that Leo III. triggered in Constantinople. King "Luitprando" used the opportunity to become "signore d'Italia". After Ravenna had been taken by the Lombards, the Exarch Paul appeared in the lagoon, "l'unico asilo che gli parve sicure", "the only refuge that seemed safe to him" (p. 8). According to his account, Byzantium and Venice only connected the interests of the "commercii", "wealth and fortress of the republic". The Doge joined the undertaking of a reconquest, even if many were against the contract with the Lombard king. According to the author, Greek fire was used and the city wall was stormed by means of a bridge made of ships, while the Exarch attacked the land side. But he was repulsed while the Venetians were taking the walls. Peredeo, the Duca di Vicenza, was killed, "cattivo Ildebrando, nipote dello stesso re longobardo". The help with the conquest earned the republic new trade privileges, and the Doge the title "Ipato". After his return, the disputes between Equilio and Eraclea continued and the doge was killed in a "zuffa", a "scuffle" or, as others say, was murdered in his house. Some historians, according to Zanotto, saw the cause of the disputes in the Doge himself and in his arrogance, heightened by Ravenna. “Comunque sia”, “whatever it may be”, the doge went down 'miserably', 'even if he had made the fatherland strong and glorious'.

Much more prosaic was the role of Orso outside of Italy, if one dealt with it at all. In 1869, Adalbert Müller wrote only succinctly about the Doge, whom he dated from 726 to 737: “Reinstates the exarch of Ravenna, whom Luitprand had driven out, into his kingdom. Is killed in a riot. "

Nation state

Orso was reinterpreted even more in the context of the nation state. In his Breve corso di storia di Venezia of 1872, dedicated to popular education , Giuseppe Cappelletti said that the Doge had 'liberated' Ravenna, the exarch Paulus, who had fled, was 'honored' in Eraclea, and that the people's assembly had agreed to support him at his request. It was decided to take action against the Lombards because their proximity threatened the Venetian 'freedom' and the 'national riches' (“nazionali ricchezze”). In addition, Orso surprisingly appeared under cover of night with 80 ships at dawn, while the Exarch was in Imola to attack from there with a land army. But the Byzantines would almost have been defeated had the Venetians not been able to overcome the walls. Regarding the temporal classification, Cappelletti admits that the reconquest took place sometime between 726 and 735. But now the envy and hatred that prevailed between the islands of the lagoon, as well as the private animosities between the tribunician families, but also the competition between Eraclea and Equilio had led to civil war. The author even knew that the opponents in the Canale dell'Arco, the later Canale Orfano, fought two days and two nights in a battle in which numerous other islanders took part - an assumption that Filiasi already support, albeit less detailed would have. In the year 737, the lagoon inhabitants finally murdered the Orso, which was so well-deserved for the fame and honor of the nation, because they did not want to tolerate a doge over them.

The same applies to the Storia popolare di Venezia dalle origini sino ai tempi nostri by Gianjacopo Fontana from 1870. Initially, he refers to Diedo (vol. 1, p. 49), published in 1751, which showed that the Doge “ Orleo ”, and that“ Orso ”was just a name that was added to it. For him was that of Emperor Leo III. The iconoclastic controversy started a storm ("tempesta") that was triggered by the emperor, to which thousands fell victims who fought against the removal of the images of the saints. For him, Orso led the fleet against Ravenna personally, it was he who founded naval schools, yes, he tried to establish a connection with the Bersagli , the snipers. Fontana is probably the first historian who thought about possible archaeological sources. In a paragraph he refers to Filiasi, who during work on the new river bed for the Sile , namely in the Valli di Cavallino , had found large quantities of lances and arrows, as well as the remains of other "old weapons", which perhaps when they were closer investigated, could have been assigned to the fighting towards the end of Orso's reign.

J. Billitzer, like most non-Venetian historians, viewed the role of Venice as more modestly. In his History of Venice from its founding to the most recent times , published in 1871, he also goes from Leo III's ban on images. out. With that "[...] he started a great fire almost all over Europe", caused the alliance between the Pope and the Longobard King, the occupation of Ravenna and the Pentapolis . With the "mighty help in ships and people" of the Venetians, the exarch managed to recapture the city. According to Billitzer, the Doge was overthrown because he had assumed rights "which he was not entitled to". Heraclea was attacked, "the doge himself was killed in a riot."

Also August Friedrich Gfrörer († 1861) accepted in his 1872 posthumous history of Venice from its inception until the year 1084 , the classification of the conquest of Ravenna in the year 729, but the causes of it were quite different. According to him, Liutprand recognized that "he was not strong enough on his own to crush the Greeks." So he offered the exarch to reinstate him in Ravenna, in order to then make common cause against Byzantium. “Liutprand also entered into negotiations with the Venetian Duke Orso for the same purpose; he presented to him that if Orso made an alliance with Lombardia, no power could prevent him from gaining independent rule over sea-Veneto, free from any Greek sovereignty. Both Eutychius and Orso must have been won, and the liberation of Ravenna, which Dandolo speaks of, was, in my opinion, much less a work of armed force than a secret agreement. ”(P. 54). In order to get Leo on board, Liutprand tried the train to Rome together with the exarch, but the Pope developed "such a superiority of spirit in private that Liutprand was moved to renounce his plan." (P. 55) . Then Gfrörer continues: “One thing is certain: Duke Orso fell as a victim of Byzantine vengeance. In order to ensure its sovereignty over Veneto during the difficult times, the basileus on the Bosporus, after Orso had been overthrown by an instigated conspiracy, abolished the civil administration of the dukes and introduced a purely military government ”(p. 57). Consequently, the Magistri militum , who followed Ursus, were Gfrörer as a mere "colonel of war appointed by the imperial court at Constantinople". Dominicus Leo ruled until 738, followed by Felix Cornicula , who brought Deusdedit back. Andrea Dandolo believed that this was done for the purpose of reconciliation, and for this reason, and in order to redress the injustice to the father, Deusdedit himself was promoted to master's degree . As Gfrörer assumes on the Byzantine initiative, Jovianus followed him again - evidence is again the title hypatus , which Jovianus carried - followed in 741 by Johannes Fabriciacus , who was blinded in 742. Deusdedit has now been elected Doge (p. 59).

After the posthumous editor Dr. Johann Baptist von Weiß had forbidden the Italian translator Pietro Pinton to annotate Gfrörer's statements in the translation, Pinton's Italian version appeared in the Archivio Veneto in the annual volumes XII to XVI. However, Pinton had enforced that he was allowed to publish his own account in the aforementioned Archivio Veneto, which did not appear until 1883. In his investigation, Pinton came to completely different, less speculative results than Gfrörer. In doing so, he held against Gfrörer that he had come to incorrect conclusions about the motivations of those involved through a wrong chronology. This can be seen from the fact that although he wrote that Andrea Dandolo had copied from Paulus Diaconus, after that he only followed the Doge's work without Gfrörer noticing the differences between the two authors. If he had read this and the other related sources, he would have noticed, according to Pinton, that Liutprand conquered the port of Classis around 728, but by no means had Ravenna. The letter to the Patriarch of Grado, to Antoninus, was not from Gregory II, but from Gregory III. as a request for help in the reconquest was sent, thus only repeating Andrea Dandolo's mistake. Eutychius had also shown himself anything but subservient to the Longobard. Orso, since Gfrörer's chronology contradicts the sources, was not overthrown by Byzantine intrigues, but by an internal Venetian civil war, as described in Andrea Dandolo's Chronicon breve . Pinton himself assumed that the reconquest of Ravenna did not take place until around 740 (pp. 40–42).

Recent research, re-dating the Battle of Ravenna (before 735 or 739/740)

Heinrich Kretschmayr , one of the best experts on the Venetian sources of his time , summed up the disillusionment with the few statements that could be made about Orso's reign . In 1905 he wrote in the first volume of his history of Venice : "As little as we know directly about his term of office - that is why we wanted to turn him into a mythical creature - so lively it seems to have been during the same period."

This is true to this day, because until recently, research assumed an uprising by the Venetian ruling class in 726/727, which in the end was no longer willing to submit to a Dux that had no significant support from the Exarchs have more. Accordingly, the magistri militum , which changes annually, can be interpreted as the result of the growing ambitions of the groups prevailing in Venice, whereas the restoration of the Dogat can be interpreted as an increase in the Byzantine central power at the expense of the local ruling class. This is how Agostino Pertusi argued in 1964 . However, since Deusdedit was to be regarded as an exponent of Malamocco and no longer of the old headquarters of Heraclea, it was assumed, in contrast, that the group of families ruling in Malamocco had simply prevailed against those of Heraclea. Accordingly, with the murder of Ursus, on the contrary, the Byzantine central power first returned in the form of the Magistri militum , against which Malamocco then resisted, as Gherardo Ortalli argued. The settlement of the epithet or title of Iubianus as Hypatus could therefore be based on a proximity to Byzantine power. It is unclear whether the aforementioned Magistri between Ursus and Deusdedit had Venetian roots. So to this day the question remains open as to which side Ursus is on, the Byzantine or the “autonomist” side.

The implied confusion regarding the dating of the battles for Ravenna found its way into modern historiography because of a single word in the description of the events by Paulus Deacon, namely the designation of the Lombard prince in connection with the battle for Ravenna as regis nepus . This was stated in 2005 by Constantin Zuckerman. Ludo Moritz Hartmann was of the opinion that the son of the Longobard king, Hildeprand, would hardly have been addressed as nepus if he had already been king at the time of the battle for Ravenna. Since it can be deduced from Longobard sources that Hildeprand became king in the summer of 735, according to Hartmann, Ravenna must have been conquered before the coronation, i.e. before 735. All reports of the first conquest of Ravenna by the Longobards - a second followed in 750/51 - ultimately go back to the sparse information in the history of the Longobard historian Paulus Diaconus . But with that the description of Andrea Dandolo also depends on Paul. The latter placed the coronation of Liutprand in the time when the coronation operators believed that King Hildeprand (who only died in 744) was dying (VI, 55). Paulus Diaconus, however, did not grant the newly crowned a large share of the royal power, and in connection with the loss of Ravenna he contrasted his capture with the manly ('viriliter') death of another defender of the city, a Vicentine . If one follows this logic, no more chronological conclusions can be drawn from the designation as a mere nepus . Ottorino Bertolini, who made clear the aforementioned chronic dependence on Paul, nevertheless also adhered to the Nepos chronology and in this way was even able to establish a temporal proximity to the dispatch of a fleet of Leo III. construct against the Italian insurgents, of which Theophanes in turn reports. Bertolini argued that this naval operation, the exact aim of which is not known, was directed against the Lombards.

As a counter-argument in favor of dating the battle for Ravenna to the late 730s, Thomas Hodgkin cited positioning in the course of Paulus Deacon's text (VI, 54). It follows the Pope's request for help from the Frankish caretaker Karl Martell , which can be dated to 739. Added to this is the date by Johannes Diaconus to the time around 740. In fact, if one casts doubt on the traditional Venetian chronology, an argument for this temporal placement by Pope Gregory III's second letter. to Karl Martell to wear. Both letters from the Pope to the Franconian housekeeper can be found in the Codex epistolaris Carolinus , but without a date. However, the first letter can be dated to the summer of 739, so that it is usually assumed that the second letter in question was dated to the time around the turn of the year 739 to 740. In the second letter, the Pope complains about the loss of what little is left in Ravenna to provide for the poor in Rome and for the church lighting in the Ravenna (“id, quod modicum remanserat preterito anno pro subsidio et alimento pauperum Christi seu luminariorum con-cinnatione in partibus Ravennacium ”). With reference to the previous year, all this has now been 'destroyed by sword and fire' (“nunc gladio et igni cuncta consumi”), namely by the Lombard kings Liutprand and Hildeprand. The reference to the previous year places the letter shortly after September 1, 739. Since there is no indication that the Lombards conquered Ravenna twice in these years, according to this timely source, the said conquest of Ravenna must fall in the autumn of 739. The Pope's letter to Antoninus von Grado, in which he asked the Venetians for help, was thus written at the same time as the second letter to Charles Martell.

Another argument against the earlier dating is that it was for Gregory III. there was no reason to speak out in such anger against the Lombards, who were allied at the time, and who had saved his predecessor from an attack by the Byzantine emperor's henchmen a few years earlier. In addition, Gregor expresses a strong expression of loyalty to the emperors in his letter, which would have been extremely unlikely in the chaotic situation around 732 ("ut zelo et amore sancte fidei nostre in statu rei publice et imperiali servicio firmi persistere"). At that time, the Pope even avoided dating the imperial reign, and his envoys were in Byzantine custody. But even at the beginning of 739 such a formulation would be surprising if, following the Chronicon Moissiacense , one assumes that the papal ambassadors asked Karl Martell for help "relicto imperatore Graecorum et dominatione, ad praedicti principis defensionem et invictam eius clementiam convertere cum voluissent", when they broke away from the Greek emperor and his rule. The rejection of the request by the Franks may have forced the Pope to look for a way to end the open rebellion against the emperor that began in the late 720s. This is also indicated by the fact that the Pope, in a letter to Boniface dated October 29, 739, resumed the imperial dating formula after many years. Gregor's successor also followed this more loyal line despite the ongoing dispute over image veneration. The open conflict with the emperor ended in the course of 739, the year in which Ravenna was also successfully retaken. The hope of Byzantine help, however, had long since vanished. This is already shown in a letter of Gregory II from 731 to Emperor Leo III. , in which he wrote to him, "He no longer has any hope of receiving help from them, 'because you cannot defend us at all!'"

Pietro Pinton had already suggested dating the battle for Ravenna to the year 740 in 1883 (see above) and again in 1893. He saw the sequence of events in the work of Paul Deacon as correct. The later dating - also by Heinrich Kretschmayr in 1905 - was taken over by Roberto Cessi in 1963 , by Jadran Ferluga in 1991 and by Pierandrea Moro in 1997. Constantin Zuckerman placed the events around Ravenna in the larger context of the "dark centuries" of Byzantium and in 2005 came to the conclusion that the conquest by the Venetians must have taken place in autumn 739.

swell

- Luigi Andrea Berto (ed.): Giovanni Diacono, Istoria Veneticorum (= Fonti per la Storia dell'Italia medievale. Storici italiani dal Cinquecento al Millecinquecento ad uso delle scuole, 2), Zanichelli, Bologna 1999 ( text edition based on Berto in the Archivio della Latinità Italiana del Medioevo (ALIM) from the University of Siena).

- La cronaca veneziana del diacono Giovanni , in: Giovanni Monticolo (ed.): Cronache veneziane antichissime (= Fonti per la storia d'Italia [Medio Evo], IX), Rome 1890, p. 94 ( digitized , PDF).

- Ester Pastorello (Ed.): Andrea Dandolo, Chronica per extensum descripta aa. 460-1280 dC , (= Rerum Italicarum Scriptores XII, 1), Nicola Zanichelli, Bologna 1938, pp. 112-114. ( Digitized from p. 112 f. )

literature

Mainly, sections about Ursus offer:

- Gherardo Ortalli : Deusdedit. In: Massimiliano Pavan (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 39: Deodato-DiFalco. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 1991.

- Gerhard Rösch : Deodato. In: Massimiliano Pavan (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 39: Deodato-DiFalco. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 1991.

- Órso. In: Enciclopedie on line. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome.

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ So the coats of arms of the much later descendants of these doges, especially since the 17th century, were projected back onto the alleged or actual members of the families (allegedly) ruling Venice since 697: "Il presupposto di continuità genealogica su cui si basava la trasmissione del potere in area veneziana ha portato come conseguenza la già accennata attribuzione ai dogi più antichi di stemmi coerenti con quelli realmente usati dai loro discendenti "(Maurizio Carlo Alberto Gorra: Sugli stemmi di alcune famiglie di Dogi prearaldici , associazione nobiliare regional veneta. Rivista di studi storici, ns 8 (2016) 35–68, here: p. 41).

- ↑ Stefano Gasparri: Hildeprand . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 5, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1991, ISBN 3-7608-8905-0 , column 16.

- ↑ Francesco Sansovino : Delle cose notabili della città di Venetia libri II , Felice Valgrisio, 1587, f. 85.

- ↑ Girolamo Bardi: Chronologia universale , Vol. 1, Giunti, Venice 1581, p. 35.

- ↑ Jacob von Sandrart : Kurtze and increased description of the origin / recording / areas / and government of the world famous Republick Venice , Nuremberg 1687, p. 12.

- ↑ Greg. II Papa, Epistolae et Canones, ep. XII [at 730], PL 89, col. 519: "et ejectis magistratibus tuis, proprios constituere magistratus" (Georgio Arnosti: La crisi iconoclasta, l'ascesa di Venecia, ei suoi patti coi Longobardi , in: CENITA FELICITER L'epopea goto-romaico-longobarda nella Venetia tra VI e VIII sec. dC , in press ( academia.edu )).

- ↑ "Same date quoque tempore prelibato Marcello duce Mortuo, qui apud civitatem novam Venecie ducatum Annis decem et octo et diebus viginti gubernaverat, cui successit Ursus Dux, qui etiam in eadem civitate sepedictum ducatum rexerat Annis XI et mensibus V" (Joh. Diac., Chronicon , II, 11, Ed.Berto , p. 98) ( Archivio della Latinità Italiana del Medioevo ).

- ↑ "Per idem tempus Leo augustus ad peiora progressus est, ita ut conpelleret omnes Constantinopolim habitantes tam vi quam blandimentis, ut deponerent ubicumque haberentes imagines tam Salvatoris quamque eius sanctae genetricis vel omnium incendio sanctoria." , Historia gentis Langobardorum , eds. Ludwig Bethmann , Georg Waitz , in: Monumenta Germaniae Historica , Scriptores rerum Langobardicarum et Italicarum saec. VI – IX . Hahn, Hanover 1878, p. 182 (6, 49) ( digitized version )).

- ↑ Ester Pastorello (ed.): Andreae Danduli Ducis Venetiarum Chronica per extensum descripta aa. 46-1280 (= Rerum Italicarum Scriptores XII, 1), Nicola Zanichelli, Bologna 1938, pp. 112-114 ( digitized from p. 112 f. ).

- ↑ Marco Foscarini : Della letteratura veneziana, con aggiunte inedite dedicata al principe Andrea Giovanelli , reprint of the edition from 1732, Venice 1854, p. 105.

- ↑ The Venetian tradition is extremely complex. In addition, there is no general overview of the numerous manuscripts. Such overviews only exist for individual collections, such as Tommaso Gar: I codici storici della collezione Foscarini conservata nella Imperiale Biblioteca di Vienna , in: Archivio Storico Italiano 5 (1843) 281–505 or Antonio Ceruti: Inventario Ceruti dei manoscritti della Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milano-Trezzano sul Naviglio (1973-1979) , Vol. I-V; or for individual countries: Cesare Foligno : Codici di materia veneta nelle biblioteche inglesi , in: Nuovo Archivio Veneto , ns IX (1906), parte I, pp. 89–128, then Giuseppe Mazzatinti: Inventari dei manoscritti italiani delle biblioteche di Francia, pubblicato dal Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione , Indici e Cataloghi V, 3 vols., Rome 1886–1888. Naturally, the situation in Italy is even more complicated: Joseph Alentinelli: Biblioteca Manuscripta ad S. Marci Venetiarum. Codices manuscripti latini , Venice 1868-1873, Vol. I – VI ( Vol. IV, digitized version ); Pietro Zorzanello: Catalogo dei codici latini della Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana di Venezia non compresi nel catalogo di G. Valentinelli , Milano-Trezzano sul Naviglio 1980–1985, Vol. 1 – III; Carlo Frati , Arnaldo Segarizzi: Catalogo dei codici marciani italiani , Modena 1909-1911, Vol. I-II ( Vol. 2, digitized ); Carlo Campana: Cronache di Venezia in volgare della Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana , Padua / Venice 2011.

- ↑ Paulus Diaconus , Historia Langobardorum , ed. Ludwig Bethmann , Georg Waitz , in: Monumenta Germaniae Historica , Scriptores rerum Langobardicarum et Italicarum saec. VI-IX . Hahn, Hanover 1878, p. 183 f. (6, 54) ( digitized version )

- ↑ Ester Pastorello (ed.): Andreae Danduli Ducis Venetiarum Chronica per extensum descripta aa. 46-1280 (= Rerum Italicarum Scriptores XII, 1), Nicola Zanichelli, Bologna 1938, p. 113 ( digitized version ). There it says: “Dux autem, cum Venetis, zelo fidei accensi, cum navali exercitu, Ravenam properantes, urbem impugnant, et Yldeprandum nepotem regis capiunt, et Peredeo ducem vicentinum viriliter pugna [n] tem occidunt: et, optenta urbe, exarchum in sede restituunt. Que quidem Venetorum probitas et fides laudabilis, testimonio Pauli gestorum Langobardorum ystoriographi, conprobantur. "

- ^ Roberto Pesce (Ed.): Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo. Origini - 1362 , Centro di Studi Medievali e Rinascimentali "Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna", Venice 2010, p. 15 f.

- ↑ Pietro Marcello : Vite de'prencipi di Vinegia in the translation by Lodovico Domenichi, Marcolini, 1558, p. 3 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Heinrich Kellner : Chronica that is Warhaffte actual and short description, all life in Venice , Frankfurt 1574, p. 2r – 2v ( digitized, p. 2r ).

- ↑ Șerban V. Marin (Ed.): Gian Giacomo Caroldo. Istorii Veneţiene , vol. I: De la originile Cetăţii la moartea dogelui Giacopo Tiepolo (1249) , Arhivele Naţionale ale României, Bucharest 2008, p. 47 f. ( online ).

- ^ "Gregorio Vescovo, Servo de servi di Dio, al diletto figliuolo Orso Duce de Venetia. Perche la Città di Ravenna, la qual'era capo di tuttel'altre, cosi causando il peccato, è stata presa dall'indegna di esser pur nominata gente Longobarda; et il figiuol nostro prestantissimo, il Signor Essarcho, dimora (come havemo inteso) appressodi voi; debba la Nobiltà tua a quello adherirsi et conlui etiandio per nome nostro poner ogn'opera con tutte le forze, acciò quella Città sia ritornata nel pristino stato alla Republica et Imperial servitio delli Signori et figliuoli nostri Leone et'Imperator, con il zelo della Santa Fede nostra, possiamo, per gratia del Signore, perseverar intrepidamente per lo stato della Republica et Imperial servitio. Il Signor Dio ti conservi, carissimo figliuolo ”(p. 48).

- ↑ Bernardo Giustiniani: Historia di M. Bernardo Giustiniano gentilhuomo vinitiano dell'origine di Vinegia, & delle cose fatte da Vinitiani. Nella quale anchora ampiamente si contengono le guerre de 'Gotthi, de Longobardi, & de' Saraceni. Nuouamente tradotta da M. Lodouico Domenichi , Venice 1545 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Leslie Brubaker, John F. Haldon : Byzantium in the Iconoclast era. c. 680-850. A History , Cambridge University Press, 2011, especially pp. 151-155.

- ↑ Marco Guazzo : Cronica di M. Marco Guazzo dal principio del mondo sino a questi nostri tempi ne la quale ordinatatamente contiensi l'essere de gli huomini illustri antiqui, & moderni, le cose, & i fatti di eterna memoria degni, occorsi dal principio del mondo fino à questi nostri tempi , Francesco Bindoni, Venice 1553, f. 167v. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Francesco Sansovino : Cronologia del mondo di M. Sansouino Divisa in tre libri , Stamperia della Luna, Venice 1580, f. 42v, under the year 726 or "Anno del Mondo" 5925.

- ↑ Michele Zappullo: Sommario istorico , Gio: Giacomo Carlino & Costantino Vitale, Naples 1609, p. 316.

- ↑ Modo dell'elettione del serenissimo prencipe di Venetia. Con il nome, e cognome di tutti i prencipi, e con gli anni che ciascuno ha vissuto nel dogato, in Eraclia, in Malamocco, & in Rialto, fino al sereniss. Nicolo Contarini aggiunte alcune dichiarationi, tratte dalle Croniche, che nell'altre impressini non si leggeuano , Francesco Cavalli, Rome 1630, o. S. ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Alessandro Maria Vianoli : Der Venetianischen Herthaben life / government, and withering / from the first Paulutio Anafesto an / bit on the now-ruling Marcum Antonium Justiniani , Nuremberg 1686, p. 36-40 ( digitized ).

- ↑ Jacob von Sandrart : Kurtze and increased description of the origin / recording / areas / and government of the world famous Republick Venice , Nuremberg 1687, p. 12 ( digitized, p. 12 ).

- ^ RIS, vol. 23, Milan 1733, col. 934.

- ↑ Samuel von Pufendorf: Introduction to the history and justice of the special states of the Roman Empire in Germany and Italy , Knoch & Eßlinger, Frankfurt 1748, p. 843.

- ^ Samuel von Pufendorf : Introduction à l'histoire générale et politique de l'Univers , Vol. 2, Chaterlain, Amsterdam 1732, p. 67.

- ↑ Pietro Antonio Pacifico: Cronaca veneta sacra e profana, o sia un compendio di tutte le cose più illustri ed antiche della città di Venezia , new edition, Francesco Pitteri, Venice 1751, p. 36 f.

- ↑ Gianfrancesco Pivati: Nuovo dizionario Scientifico e curioso sacro-profano , Vol 10, Milocco, 1751, p.167..

- ↑ Augustinus Valiero: Dell'utilità che si può ritrarre dalle cose operate dai veneziani libri XIV , Bettinelli, Padua 1787, p. 17 f.

- ↑ Augustinus Valiero: Dell'utilità che si può ritrarre dalle cose operate dai veneziani libri XIV , Bettinelli, Padua 1787, p. 20.

- ↑ Vincentius Briemle, Johann Josef Pock: The through the three parts of the world, Europe, Asia and Africa, especially in the same to Loreto, Rome, Monte-Cassino, no less Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Nazareth, Mount Sinai, [et] c. [Etc. and other holy places of the promised land employed devotional pilgrimage , first part: The journey from Munich through whole Welschland and back again , Georg Christoph Weber, Munich 1727, p. 188 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Ferdinand Ludwig von Bressler and Aschenburg: Today's Christian Sovereigns of Europe, That is: A brief Genealogical and Political Outline / Darinnen des Heil.Röm.Reiches / all kingdoms / states and sovereigns princes of Europe historical main periods; the potentates and rulers now living there with their relatives; the most distinguished districts and dioceses in the same places; as are many civil servants at the courts / in respectable colleges, in important governemas and in the highest military service; In addition to famous families attached to each country, knight orders / societies and now and then subsisting envoys are presented according to geographical order , vol. 6, Johann Georg Steck, Breslau 1699, p. 1101. ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Johann Friedrich LeBret : State history of the Republic of Venice, from its origin to our times, in which the text of the abbot L'Augier is the basis, but its errors are corrected, the incidents are presented in a certain and from real sources, and after a Ordered the correct time order, at the same time adding new additions to the spirit of the Venetian laws and secular and ecclesiastical affairs, to the internal state constitution, its systematic changes and the development of the aristocratic government from one century to the next , 4 vols., Johann Friedrich Hartknoch , Riga and Leipzig 1769–1777, Vol. 1, Leipzig and Riga 1769, pp. 96–98 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ On theater during this period: Cesare De Michelis: Teatro e spettacolo durante la Municipalità provvisoria di Venezia, maggio-novembre 1797 , in: Mario Richter: Atti del Convegno di studi su Il teatro e la rivoluzione francese , Accademia Olimpica, 1991, p 263-288.

- ↑ Pietro Themelly: Il teatro patriottico tra rivoluzione e impero , Bulzoni, 1991, p 160th

- ^ Studi Veneziani (1993), p. 219.

- ↑ Paolo Bosisio: Le héros dans la tragédie Jacobine italienne. Dramaturgie et interprétation , in: Arzanà 14 (2012) 131–146 ( online ).

- ^ Carlo Antonio Marin : Storia civile e politica del commercio de 'veniziani , 8 vols., Coleti, Venice 1798-1808, vol. 1, Venice 1798, p. 174.

- ^ Carlo Antonio Marin: Storia civile e politica del commercio de 'veniziani , 8 vols., Coleti, Venice 1798-1808, vol. 1, Venice 1798, p. 176.

- ^ Antonio Quadri : Otto giorni a Venezia , Molinari, 1824, 2nd ed., Part II, Francesco Andreola, Venice 1826, p. 60 f.

- ^ Carlo Antonio Marin: Storia civile e politica del commercio de 'veniziani , 8 vols., Coleti, Venice 1798-1808, vol. 1, Venice 1798, p. 182 f.

- ↑ Jacopo Filiasi : Memorie storiche de 'Veneti primi e secondi , vol. 5: Storia dei Veneti primi sotto il dominio dei Eruli e Goti , 2nd edition, Padua 1812, pp. 213-241.

- ↑ Quadro SINOTTICO di tutte la Mutazioni politiche e governative incontrate dalla citta dallo stato e dalla provincia di Venezia dall'anno CCCCXXI dell'Era volgare a tutto Agosto MDCCCXLVIII compilato ad uso delle persone d'affari ed a comodo degli studiosi since FDSAP , o . O., [1848], pp. 1 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ^ Giovanni Bellomo: Lezioni di storia del medio evo , G. Antonelli, Venice 1852, p. 24 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Samuele Romanin : Storia documentata di Venezia , 10 vols., Pietro Naratovich, Venice 1853-1861, 2nd edition 1912-1921, reprint Venice 1972.

- ^ Samuele Romanin: Storia documentata di Venezia , Vol. 1, Pietro Naratovich, Venice 1853, p. 111.

- ^ Samuele Romanin: Storia documentata di Venezia , Vol. 1, Pietro Naratovich, Venice 1853, p. 113.

- ^ Samuele Romanin: Storia documentata di Venezia , Vol. 1, Pietro Naratovich, Venice 1853, p. 115.

- ↑ Francesco Zanotto: Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia , Vol. 4, Venice 1861, pp. 8-10 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Adalbert Müller : Venice - His art treasures and historical memories. A guide in the city and on the neighboring islands , 1st edition, HF Münster, Venice / Triest / Verona 1857, p. 42.

- ↑ Giuseppe Cappelletti : Breve corso di storia di Venezia condotta sino ai nostri giorni a facile istruzione popolare , Grimaldo, Venice 1872, pp. 21-24.

- ↑ This is Giacomo Diedo: Storia della Repubblica di Venezia dalla sua fondazione sino l'anno MDCCXLVII , Vol. 1, Andrea Poletti, Venice 1751 ( digitized ).

- ↑ Gianjacopo Fontana: Storia popolare di Venezia dalle origini sino ai tempi nostri , Vol 1, Giovanni Cecchini, Venice 1870, p.54..

- ↑ This is what Paul the deacon called him.

- ↑ Gianjacopo Fontana: Storia popolare di Venezia dalle origini sino ai tempi nostri , Vol 1, Giovanni Cecchini, Venice 1870, p.59..

- ↑ J. Billitzer: history of Venice from its inception up to the latest time f, coalfish, Trieste / Venice / Milan, 1871, p. 5

- ↑ August Friedrich Gfrörer: History of Venice from its foundation to the year 1084. Edited from his estate, supplemented and continued by Dr. JB Weiß , Graz 1872, ( digitized version ).

- ^ Pietro Pinton: La storia di Venezia di AF Gfrörer , in: Archivio Veneto (1883) 23–63 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Paulus Diaconus (VI, 49) says: "Liutprandus Ravennam obsedit, Classem invasit atque destruxit."

- ^ Heinrich Kretschmayr : History of Venice , 3 vol., Vol. 1, Gotha 1905, p. 44 f.

- ↑ "Il ritorno di nuovo ai duces ... è da intendere come un ritorno alla normalità, cioè alla sovranità bizantina dell'esarco." (Agostino Pertusi: L'impero bizantino e l'evolversi dei suoi interessi nell'alto Adriatico , in : Le origini di Venezia , Florence 1964, p. 69).

- ↑ "il trasferimento della sede a Malamocco […] die ad indicare una ripresa del processo autonomistico" (Gherardo Ortalli: Venezia dalle origini a Pietro II Orseolo , in: Longobardi e Bizantini , Turin 1980, pp. 339-428, here: p . 367).

- ↑ This and the following according to Constantin Zuckerman: Learning from the Enemy and More: Studies in “Dark Centuries” Byzantium , in: Millennium 2 (2005) 79–135, esp. Pp. 85–94.

- ^ Ottorino Bertolini: Quale fu il vero obiettivo assegnato in Italia da Leone III "Isaurico" all'armata di Manes, stratego dei Cibyrreoti? , in: Byzantinische Forschungen 2 (1967) 40 f.

- ↑ Codex Carolinus 2, edited by Wilhelm Gundlach , in MGH Epp., III, p. 477.

- ↑ Chronicon Moissiacense, ed. By Georg Heinrich Pertz , MGH Scriptores I, Hannover 1826, p. 291 f.

- ↑ Quoted from: Stefan Weinfurter : Karl der Große. Der heilige Barbar , Piper, München und Zürich 2015, p. 84 and note 18 on p. 274, where the author cites as evidence: Migne, Patrologia Latina 89, Sp. 519, and he quotes from the letter: “cum tu nos defendere minime possis ”. It is about the Pope's Epistola XII, Sp. 511-521 ( reference in Sp. 519 ).

- ^ Pietro Pinton: Longobardi e veneziani a Ravenna. Nota critica sulle fonti , Balbi, Rome 1893, p. 30 f. and Ders .: Veneziani e Longobardi a Ravenna in: Archivio Veneto XXXVI11 (1889) 369-383 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Heinrich Kretschmayr: History of Venice , 3 vol., Vol. 1, Gotha 1905, p. 48: “Immediately afterwards, in 741, Pope Gregor III. died".

- ^ Roberto Cessi: Venezia ducale , vol. I: Duca e popolo , Venice 1963, p. 103.

- ↑ Jadran Ferluga : L'esarcato , in: Antonio Carile (ed.): Storia di Ravenna , Vol. II / 1: Dall'età bizantina all'età ottoniana. Territorio, economia e società , Venice 1991, pp. 351–377, here: p. 371.

- ↑ Pierandrea Moro: Venezia e l'occidente nell'alto medioevo. Dal confine longobardo al pactum lotariano , in: Stefano Gasparri, Giovanni Levi, Pierandrea Moro (eds.): Venezia. Itinerari per la città , Il Mulino, Bologna 1997, p. 42.

- ↑ Constantin Zuckerman: Learning from the Enemy and More: Studies in “Dark Centuries” Byzantium , in: Millennium 2 (2005) 79–135, especially pp. 85–94.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Marcello Tegalliano |

Doge of Venice 727-737 |

Diodato Ipato |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ipato, Orso |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Doge of Venice |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 7th century or 8th century |

| DATE OF DEATH | 737 |