Eutychius (Exarch)

Eutychius was an Eastern Roman patrician and valet , but above all the last exarch of Ravenna . The Liber Pontificalis calls Eutychius, who led this office between 727 and 751, as patricius eunuchus , which would fit the office of Cubicularius . His first task should be to overthrow the Pope, who defended himself against the anti-image policies of the Byzantine emperor. But an equalization was achieved in 728. When the Lombards succeeded in conquering Ravenna, or at least from Classe, the naval port a little further south, towards the end of the 730s, Eutychius fled to the Venice lagoon . There he received support so that in 739 or 740 his official seat of Ravenna could be recaptured with the help of a Venetian fleet. This was the first time that the cities from which the Republic of Venice emerged appeared as a maritime power, which resulted in an unusually intensive examination of the event in the history of Venice. In 743 the Lombards invaded the area of Ravenna again, but their king Liutprand let himself be dissuaded from the enterprise. Only his successor conquered Ravenna in 751. This time Venice did not intervene. Nothing is known about the exarch from 743 onwards.

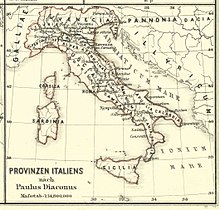

Administration as Exarch of Ravenna

Eutychius was the last exarch of Ravenna, an office he held between 727 and 751. When he took office, he got into a series of overlapping conflicts.

He was sent to Italy after the murder of his predecessor Paul , who had been in conflict with the Pope. Eutychius landed in Naples and initially allied himself with the Lombard king Liutprand against Pope Gregory II , but without being able to overthrow him. On the contrary, he was appointed by Pope with excommunication occupied. In 728, the Exarch and Pope were reconciled, allegedly through Liutprand's mediation. The Pope even supported Eutychius' suppression of the uprising instigated by Tiberios Petasius in Tuscany .

In Italy, the effects of the Byzantine iconoclasm could be felt in these battles , which was possibly caused by a decree of Emperor Leo III. had been triggered. The Italian territories fought against the destruction of the paintings, which the emperor had already begun in Constantinople, but also against his tax collection. A letter from Pope Gregory II from around 730 indicates the expulsion of the imperial magistrates as well as the establishment of their own.

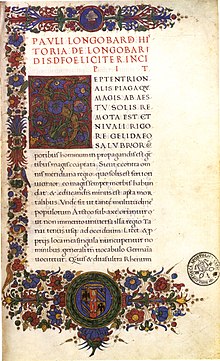

In his Historia Langobardorum , Paulus Diaconus provided the epic images of the iconoclastic controversy that appeared again and again in later descriptions, for example when he was told by Emperor Leo III. reports how he forced all residents of the imperial capital to burn all the images of the Savior, his mother and all the saints in the middle of the city in fire (VI, 49). During this time of theological disputes, which possibly affected society as a whole, pirate fleets of the Muslim conquerors known as Saracens also appeared in the central and upper Adriatic, as did their troops on the Iberian Peninsula and in Aquitaine , which threatened the Frankish Empire .

In addition, a new phase of Lombard expansion began in mainland Italy under King Liutprand (712-744), whose intention was to conquer the imperial territories including Rome and Ravenna. In 725, Liutprand allied himself with the Frankish houseman Karl Martell , whom he supported in Bavaria and against the Muslim Arabs and Berbers advancing north from the Iberian Peninsula . In 738 these conquerors, known as the Saracens, invaded Provence . At that time Karl Martell was on a campaign in Saxony. For him the Longobard king Liutprand advanced with an army, which the invaders evaded without a fight. This long-term stable alliance between Karl and Liutprand prevented the Pope from being supported by the Franks, because he was in conflict with Liutprand. In 737 Liutprand even adopted Karl's son Pippin.

As early as 728, one year after taking office, the Longobard king is said to have invaded the Byzantine area around Ravenna. He later conquered the city and drove out the exarch who lived there. Today the years 737 to 740 are preferred as the period of the Longobard occupation of Ravenna. In any case, Eutychius fled from the conquerors to the Venetian lagoon , where Archbishop John V also fled, as the author of the Liber pontificalis ecclesiae Ravennatis reports. He also reports that Ravenna fell through betrayal (XXXIX).

At an unspecified time, at the request of the Pope, the Venetians sent their navy under the leadership of Doge Ursus , expelled the Lombards from Ravenna, with the king's son falling into their hands, and thus enabled the exarch to return to his office. It can no longer be decided whether the gift of six onyx columns by the exarch to the Pope is related to this.

This battle for Ravenna, in which the Venetians achieved greater military and political importance for the first time in their history, led to extensive reinterpretations in the much later tangible Venetian historiography, which was subject to a pronounced state doctrine, the pivotal point of which was the temporal Classification of the event (see section Reception). If the date of the conquest of Ravenna is accepted in the year 737, then this happened at a time when a civil war was raging in the Venetian lagoon, to which the Doge fell victim (which the Lombard chronicler Paulus does not call the deacon), and 740 was ruling there not a doge at all, but a Magister militum .

Little is known about Eutychius about the time after his reinstatement in office. In 743 another Lombard incursion was averted by the intervention of Pope Zacharias II , who was able to dissuade Liutprand from conquering Ravenna. It is not certain whether Eutychius was still exarch at this time, but the Chronicon Salernitanum 4.13–15 suggests that he remained in office until the Lombard conquest. This conquest took place in 751, but only under King Liutprand's successor Aistulf (744-757).

Reception and embedding in historiography

For Venice's historians, the reconquest of Ravenna was such an important event - after all, it was the first military strike of the Venetian fleet and at the same time groundbreaking in that it took place on the side of Constantinople - that its classification was of the greatest importance. The Venetian tradition was largely displaced by the chronicle of Doge Andrea Dandolo from the 14th century, which, like a bottleneck, not only bundled the legends and myths from the early days of Venice, but also permanently added them to the basis of the development of Venetian myths. In it developed a historiography controlled by the state leadership, which was adhered to until the end of the republic. As a result, most of the works of the time before Andrea Dandolo disappeared, as the doge and historian Marco Foscarini noted in 1732. For many authors, the iconoclasm was consistently the supreme guideline for action of the popes as well as all "Italians", to which all political thinking was allegedly subordinated. In order to prove this, however, the sequence of events, and therefore the entire chronology, in particular the battles for Ravenna, had to be adjusted.

Paulus Diaconus describes, around two centuries before the beginning of Venetian historiography in his Lombard history (VI, 54), after he reports of the successful alliance between Liutprand and Karl Martell (739), like the regis nepus , the nephew of the Lombard king, the humiliating expulsion from the recently conquered Ravenna had to accept, where he was also captured by Venetians. This report was published around 1000 by Johannes Diaconus , who apparently had insight into a letter from Pope Gregory III. to Antoninus, who had taken Patriarch of Grado . In this letter, the Pope asked for help in recovering Ravenna for the Emperors Leo and Constantine. Johannes reproduced the wording of the letter, but without date and place, at least placed it in the days of the Magister militum Julianus Hypathus , which, according to traditional chronology, corresponded to the time around 740. The aforementioned Doge Andrea Dandolo delivered a very similar report in the middle of the 14th century, who in turn invokes Paulus Diaconus, because the courage and faith of the Venetians are proven by “testimonio Pauli gestorum Langobardorum ystoriographi”. But the addressee of the papal letter quoted by Dandolo was now Dux Ursus , which placed the letter between about 727 and 736. Not only did he move the battle for Ravenna more than a decade ago, but he also confused Pope Gregory III. (731–741) with Gregory II. (715–731), which means that the fighting took place between 727 and the beginning of 731. This is the most cited date for combat operations well into the 21st century.

The oldest vernacular chronicle, the Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo , also from the 14th century , depicts the events, which are obviously not (no longer) understandable even for historians, on a largely personal level. At the same time, this chronicle follows another largely from Andrea Dandolo independent narrative thread. Ursus, the doge, was honored by the "imperial maestade ... molto honorado passando per le soe contrade". What is meant is the Byzantine emperor, who traveled through the lagoon cities and honored the doge with high honors. On this occasion he even had Ursus “constituido signor gieneral de tuta la soa provincia” (p. 15). The chronicler assumes that there was a formal act of installation by the emperor in his presence, which also referred to the Byzantine 'province'. When there was perfect peace after the fall of the Doge (“reducti ad perfecta paxe”), the lagoon towns appointed an annually changing master to rule (“se deliberono far un rector et cavo tra loro, el qual si dovesse mudar ogni anno”). This sequence of events was to remain for more than half a millennium, but the alleged journey of the emperor to the lagoon and the appointment of the doge as “signor general” of the entire Byzantine 'province' disappear from the historiography.

A simple version had prevailed around 1500, but was later embellished. Pietro Marcello said in 1502 in his work, later translated into Volgare under the title Vite de'prencipi di Vinegia , that Ravenna had been occupied by the Lombards under Ursus, so that his exarch turned to the Venetians for help. The Pope also asked them to take up arms and help the exarch against the "insolentissimi Barbari". 'In order to show obedience to the Pope' (“per ubidire al Papa”) they sent a large fleet to Ravenna, which they immediately conquered and immediately returned to the exarch.

The Frankfurt lawyer Heinrich Kellner , who in his Chronica Das ist Warhaffte actual and short description, all of the life in Venice , which was published in 1574, refers heavily to Marcello, but at the same time made the Venetian history better known in the German-speaking area, apparently misunderstood the word "Esarco" and believes the Exarch is a proper name. This "Esarcus" asked for help in Venice, which agreed to retake Ravenna. The Venetians did this because the Pope “admonished them” to wage war against the “hard-working Barbaros”.

According to the brief chronicle of Gian Giacomo Caroldo , which he completed in 1532, “Orso” was involved in the battle for Ravenna because the Lombard king Liutprand had laid siege to Ravenna, with “Capitano di quella impresa era Ildebrando nepote della Maestà Sua”. The son of the Longobard king was the commander of this enterprise. Together with “Peredeo Duca Vicentino” he destroyed the army of Ravenna and in the end the city came under the rule of the Longobards (“venne sotto il dominio de Longobardi”). In order to escape the anger of the barbarians (“per fuggir il furor de Barbari”), the Exarch went to “Venetia”, “like a safe haven”. Pope Gregory wrote a “breve” to “Orso Duce”, as the author is certain. Basically he wrote: Bishop Gregory, Servant of the Servants of God, to his beloved son Orso Duca de Venetia. Because the city of Ravenna, which was the head of all others, was taken by the unworthy Lombards, and our excellent son, the Lord Exarch, is staying with you (as we have learned), your "Nobiltà" should share the city with him bring back under the rule of the Lords and Our Sons Leo and Constantine. With religious zeal, the Doge prepared a fleet of strong forces and attacked Ravenna. "Ildebrando" was captured while "Peredeo" was killed. The exarch was reinstated. The “virtuoso operationi” of the “Duce Veneto” in honor of the Catholic faith were celebrated with the testimony of the “Paulo historico Longobardo”, as Caroldo also expressly notes. In contrast to Marcello, Caroldo emphasizes extremely strongly the struggle for Ravenna and the attitude of the Venetians to it, while he hardly devotes a line to the internal struggles that, according to Marcello, led to the doge's fatal death.

Bernardo Giustiniani, who in his Historia, printed in 1545, reproduces the speech of the exarch, who fled the Lombards from Ravenna before the people's assembly in Venice (S. CXLI - CXLIIII), closes with the words: "Tutto il consiglio fu del parere del Doge Orso", the popular assembly was therefore unanimous in the opinion of the Doge. He also knows how to report the exact strength of the fleet. According to this, 80 ships, 20 of them large, headed for Ravenna, pretending to support the emperor against the Saracens (S. CXLIIII). The masts of the large ships were, according to the author, so high that the besiegers could overcome the city walls. Giustiniani also explicitly refers to the Historia of the Longobard " Paolo Diacono " (CXLV) in this description . But he constructs a completely different context by drawing together events that are relatively far apart in time. Emperor Leo, "huomo di nessuna virtu, ma ben di notabile perfidia, & avaritia" ('man without any virtue, but of remarkable slyness and greed'), according to the author, continued to try, as Giustiniani writes, to ruin the empire. Because after the two-year siege of Constantinople by the Saracens (717–718), in which, according to Giustiniani, two times 300,000 people were killed, the emperor plundered the churches. When the Pope resisted the destruction of the pictures, the Emperor tried to have him murdered. In Ravenna, where Orso was still with the fleet that had conquered the city, there were also riots. According to Giustiniani, views emerged in Orso's camp, such as the one that the emperor was “peggiore di tutti i barbari, & di Macometto anchora”, that the emperor was worse than the barbarians, by which the Lombards were probably meant, and even worse than him Prophet Mohammed . So the Christians needed a new emperor, some thought of Karl Martell , the Frankish king (CXLVI f.). But the Pope preferred to advertise his cause with letters to all potentates. The Venetians brought the relics of the iconoclastic martyrs to their churches, such as St. Theodore to San Giorgio Maggiore (who became the patron saint of Venice). An assembly of bishops excommunicated the emperor. Giustiniani's evaluations have been upheld for a long time, especially with regard to the iconoclasm and Leo's role in it, but are now considered refuted. The admirers of images, whose sources have been handed down, got too much on the person of the emperor; at the same time, they exaggerated the radical nature of the destruction.

The attempts to place the reign of Doge Ursus in chronological order show how uncertain the chronology was, and how starkly it contrasted with the rampant details provided by some historians. Marco Guazzo states in his cronica in 1553 that "Orso Ipato terzo doge di Venezia" was made Doge in 721. After that he was in office for nine years, so until 730. After that, Venice was without a Doge for six years "reggendosi per altri magistrati, & uffici". The lagoon ruled itself through other magistrates and offices, which probably meant the magistri militum , which ruled for a year . Francesco Sansovino , on the other hand, wrote in his Cronologia del mondo in 1580 under the year 726 (thus classifying the beginning of his rule): "O rso Ipato, cioè Cōsolo imperiale", "è morto dal popolo", "Orso Ipato, i.e. imperial consul", is killed by the people. Only after five years did they return to the Dogat by making their son Deodato a Doge. In his Sommario istorico in 1609, however, Michele Zappullo set the election year to 724 and the year of death to 729. In 1630, the election mode again mentions the year 726 for Orso as the election year, plus a reign of eleven years and five months, i.e. up to around 737.

In Alessandro Maria Vianoli's Historia Veneta from 1680 (Volume 1), which appeared six years later in German, “Duke” Ursus called on his voters to “all sorts of hard work”. After “the Lombard king” had taken Ravenna, and “Esarcus, who at that time ruled the same / in the name of the emperor / fled Venice / called the Hertzog for Hülff / meanwhile also a pleading and pathetic letter to him from Pope Gregorio II. arrived ”to retake Ravenna. Although he was in an alliance with Liutprand, he obeyed the Pope and wanted to defend "the Esarcum" at the same time. The "Armada" "/ which bit in 80th warships" conquered the city "with the help of the night". The victory was all the greater "because Perendius remained dead in it / and Ildebrand was taken prisoner to Constantinople". After the town was handed back to "Esarcus", there was a dispute between Grado and Aquileia because "Calixtus, the patriarch of Aquileia, took away two islands / named Centinara and Massone". However, under papal pressure and in view of the Doge's armor, he had to surrender it. “Kurtz after his death”, reports Vianoli, “the regiment of the city was changed / sintemalen the whole community bore a great disgust / in Eraclea, than to come together in a shameful murder pit / there. Because of this, / with the greatest unanimity / the entire island of Malamocco ", where" finally no more relatives / but in the same position Maestri di Cavalieri, or knight masters / who were to remain in such office for only one year / to be chosen / has been decided ". Vianoli expressly states that the first of these magistri militum was elected unanimously.

But the slow process of legend formation was by no means over. Augustinus Valiero claimed in 1787 that Orso had won the Venetian youth for the fleet, similar to Vianoli, so that within a few years not only the pirates could be defeated, but also the Greek fleet, and that the Venetian naval forces succeeded in conquering Ravenna. The Exarch Paul had convinced Venice of the danger of the Lombards and of their deceit, and the Pope had also urged a counter-attack against the barbarians. This is how Ravenna was retaken. However, when an envoy of the emperor demanded the destruction of the images in the churches of the lagoon, the doge referred to the conquest and return of Ravenna and the constant support of Constantinople in the fight against the Lombards. But in church affairs, the Venetians would only follow the Pope.

Johann Friedrich LeBret believes that the Doge played a decisive role in the “reconquest of Ravenna” (the author offers the years 728 and 730 in marginalia). He believes that the city will be split into two parties, one that is friendly to images and one that is hostile to images. After the exarch "Paul" was murdered, according to LeBret, the Lombard king moved outside the city. The author takes a highly critical view of the tradition since Andrea Dandolo: “Dandulus is sending a letter through which this Pope [Gregory II] is said to have exhorted the Venetians to recapture Ravenna. But we are not inclined to honor the Venetians by quoting this letter ”. At the same time, in a footnote, he also rejects the Sagornina , i.e. the chronicle of Johannes Diaconus , at this point, because he has "but otherwise all the marks that he has been placed under". In addition, the letter from Johannes was not addressed to the Doge, but to "the Patriarch of Grado, Antonius", the author insists. Nevertheless, De Monachis also reported that "the Pope had asked the Venetians to snatch Ravenna from the hands of the enemy." According to LeBret, the Venetians saw subordination to the Byzantine sea power as more advantageous. Therefore "Eutychius", the exarch who fled into the lagoon, found "an inclined ear", especially since "this was a weyde for his warlike spirit". "Hildebrand, a nephew of the Luitprand, who presumably commanded the besieged city, was captured and taken to Veneto." Incidentally, the author mentions that the Archbishop of Ravenna, Johannes, had also fled into the lagoon, "Peredeus, Duke of Vicenza ... was killed in the battle ”. For LeBret, the Doge's epithet was an expression of the "consular dignity with which the Greek emperors usually adorned those who had distinguished themselves to their advantage." The honorary title thus serves as evidence for the reconquest of Ravenna by the Doge.

The following year Carlo Antonio Marin brought out the first volume of his Storia civile e politica del commercio de 'veniziani . For him, the Venetians, again under Orso, experienced for the first time that they could not only defend their islands and trade under the suzerainty of the emperor, but that they were also able to wage war with their navy outside of their territory to lead. For the siege of Ravenna - Marin explicitly assumes the intention to make a profit, without which the Venetians would not have jeopardized their freedom - 60 ships were equipped with him. In order to keep the Lombards in the dark about their intentions, they faked a campaign against the Saracens. After the conquest, Marin believes that the Venetians were the economic masters of the Adriatic, Ravenna and the East, and he was 'sure' that the Exarch would have paid for the war costs, that the Venetians were allowed to set up trading houses and that they were given preferential treatment with taxes .

For Antonio Quadri , it was now certain, after the victory over the Lombards in the battle for Ravenna, the emperor was given the title of Ipato .

Even Jacopo Filiasi had 1812 in his storiche Memorie de 'Veneti a broader representation of trying to fill the nearly 30 pages. Filiasi referred much more strongly to the older sources, above all to the chronicle of Doge Andrea Dandolo from the middle of the 14th century. The author also included the political environment, which was determined by the iconoclasm of the East, against which all “Itali” resisted, and against which Venice rose up. After a failed assassination attempt on the Pope, the emperor tried violence, but the Venetians resisted. There is even talk of a counter-emperor who they wanted to bring to Constantinople , an alleged undertaking that the Pope is said to have prevented the Venetians from doing. As Filiasi notes, however, the Venetian sources are in the dark if they make any hints. Emperor Leo succeeded in building a pro-Byzantine party that threw Ravenna into discord (“pazza discordia”), an opportunity the Lombards used to conquer the city. After Filiasi, the new exarch Eutychios fled to Venice and placed himself under the protection of Orsos, under whose leadership Ravenna was recaptured. Filiasi believes that the risk of becoming 'the prey of the barbarians' should have been enough to agree, but 'only the people advance in good faith, but the leaders have completely different goals' - and in the end only these advantages would result the fights. The emperor, who still wanted to enforce iconoclasm against the resistance of the Pope, tried several times to conquer Ravenna, but finally - again a new process - Venice defeated its fleet in front of the city.

Giovanni Bellomo considered Orso's battle for Ravenna in his anecdotal representation of the Middle Ages for a wide audience, his Lezioni di storia del medio evo , to be so important that it found its way into his work published in 1852. For him, Orso was 'filled with warlike spirits' (“pieno di spiriti marziali”). He confidently dated the surprise attack on Ravenna to 729, and he also knew that the fleet comprised 80 ships. Like his predecessors, he mentions the honor of the consul title that Leo III gave him. transmitted.

In the first volume of his ten-volume opus Storia documentata di Venezia, Samuele Romanin devoted a great deal of attention to the events . Romanin's starting point, however, was exactly what most of the other historians of his time have now left out, namely the iconoclast and the role of emperor and pope. He reports of attempts to assassinate the Pope, of the role of the Lombard king, who in his eyes is above all glorious, of the arrogance of the emperor, only to pause and admit that the tradition is contradictory, confused, 'confused' ("imbrogliato"), that the historians also worked 'poorly' and 'negligently', making it very difficult and sometimes even impossible to reconstruct the events (p. 111). So Romanin can for example the contradicting actions of the Pope, who allied himself with the Lombards and excommunicated the exarchs, but still campaigned for the reconquest of Ravenna, who tried Leo III. convincing with letters and at the same time discrediting the Lombards, hardly reconciling them in the context of his moral historiography. He therefore dates the conquest of Ravenna to the time from 727 to the beginning of 728 (p. 113), reports of the battles between the allies and the opponents of the emperor in Ravenna, of the death of exarch Paul and his replacement by Eutyches in 728. Gregory succeeded, according to Romanin, with mere words to keep the exarchs and the Lombards from conquering Rome (p. 115).

More closely tied to historiographical conventions, Francesco Zanotto wrote in his work Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia of 1861. The starting point for the upheavals was also the iconoclasm of Leo III. triggered in Constantinople. King "Luitprando" used the opportunity to become "signore d'Italia". After Ravenna had been taken by the Lombards, the Exarch Paul appeared in the lagoon, "l'unico asilo che gli parve sicure", "the only refuge that seemed safe to him" (p. 8). According to his account, Byzantium and Venice only connected the interests of the "commercii", "wealth and fortress of the republic". The Doge joined the undertaking of a reconquest, even if many were against the contract with the Lombard king. According to the author, Greek fire was used and the city wall was stormed by means of a bridge made of ships, while the Exarch attacked the land side. But he was repulsed while the Venetians were taking the walls. Peredeo, the Duca di Vicenza, was killed, "cattivo Ildebrando, nipote dello stesso re longobardo". The help with the conquest earned the republic new trade privileges, and the Doge the title "Ipato".

Much more prosaic was the role of Orso outside of Italy, if one dealt with it at all. In 1869, Adalbert Müller wrote only succinctly about the Doge, whom he dated from 726 to 737: “Reinstates the exarch of Ravenna, whom Luitprand had driven out, into his kingdom. Is killed in a riot. "

Orso was reinterpreted even more in the context of the nation state. In his Breve corso di storia di Venezia of 1872, dedicated to popular education , Giuseppe Cappelletti said that the Doge had 'liberated' Ravenna, the exarch Paulus, who had fled, was 'honored' in Eraclea, and that the people's assembly had agreed to support him at his request. It was decided to take action against the Lombards because their proximity threatened the Venetian 'freedom' and the 'national riches' (“nazionali ricchezze”). In addition, Orso surprisingly appeared under cover of night with 80 ships at dawn, while the Exarch was in Imola to attack from there with a land army. But the Byzantines would almost have been defeated had the Venetians not been able to overcome the walls. Regarding the temporal classification, Cappelletti admits that the reconquest took place sometime between 726 and 735. In the year 737, the lagoon inhabitants finally murdered the Orso, which was so well-deserved for the fame and honor of the nation, because they did not want to tolerate a doge over them.

The same applies to the Storia popolare di Venezia dalle origini sino ai tempi nostri by Gianjacopo Fontana from 1870. For him, that of Emperor Leo III. The iconoclastic controversy started a storm ("tempesta") triggered by the emperor, to which thousands fell victim who resisted the removal of the icons. Orso personally led the fleet against Ravenna for him.

J. Billitzer, like most non-Venetian historians, viewed the role of Venice as more modestly. In his History of Venice from its founding to the most recent times , published in 1871, he also goes from Leo III's ban on images. out. With that "[...] he started a great fire almost all over Europe", caused the alliance between the Pope and the Longobard King, the occupation of Ravenna and the Pentapolis . With the "mighty help in ships and people" of the Venetians, the exarch managed to recapture the city.

Also August Friedrich Gfrörer († 1861) accepted in his 1872 posthumous history of Venice from its inception until the year 1084 , the classification of the conquest of Ravenna in the year 729, but the causes of it were quite different. According to him, Liutprand recognized that "he was not strong enough on his own to crush the Greeks." So he offered the exarch to reinstate him in Ravenna, in order to then make common cause against Byzantium. “Liutprand also entered into negotiations with the Venetian Duke Orso for the same purpose; he presented to him that if Orso made an alliance with Lombardia, no power could prevent him from gaining independent rule over sea-Veneto, free from any Greek sovereignty. Both Eutychius and Orso must have been won, and the liberation of Ravenna, of which Dandolo speaks, was, in my opinion, much less a work of armed force than a secret agreement ”(p. 54). In order to get Leo on board, Liutprand attempted the train to Rome together with the exarch, but the Pope developed "such a superiority of spirit in private that Liutprand was moved to renounce his plan" (p. 55). Then Gfrörer continues: “One thing is certain: Duke Orso fell as a victim of Byzantine vengeance. In order to ensure its sovereignty over Veneto during the difficult times, the basileus on the Bosporus, after Orso had been overthrown by a conspiracy, abolished the civil administration of the dukes and introduced a purely military government ”(p. 57). Consequently, the Magistri militum , who followed Ursus, were Gfrörer as a mere "colonel of war appointed by the imperial court at Constantinople".

Pietro Pinton reproached Gfrörer for having come to incorrect conclusions about the motivations of those involved through a wrong chronology. This can be seen from the fact that although he wrote that Andrea Dandolo had copied from Paulus Diaconus, after that he only followed the Doge's work without Gfrörer noticing the differences between the two authors. If he had read this and the other related sources, he would have noticed, according to Pinton, that Liutprand conquered the port of Classis around 728, but by no means had Ravenna. The letter to the Patriarch of Grado, to Antoninus, was not from Gregory II, but from Gregory III. as a request for help in the reconquest was sent, thus only repeating Andrea Dandolo's mistake. Eutychius had also shown himself anything but subservient to the Longobard. Pinton is the first to assume that the reconquest of Ravenna did not take place until 740 (pp. 40–42).

New dating of the battle for Ravenna

The implied confusion regarding the dating of the battles for Ravenna found its way into modern historiography because of a single word in the description of the events by Paulus Deacon. This word is the name of the Lombard king's son in connection with the battle for Ravenna as regis nepus . This was stated in 2005 by Constantin Zuckerman. According to Zuckerman, Ludo Moritz Hartmann was of the opinion that the son of the Lombard king, Hildeprand, would hardly have been addressed as nepus if he had already been king at the time of the battle for Ravenna. Since it can be deduced from Longobard sources that Hildeprand became king in the summer of 735, according to Hartmann, Ravenna must have been conquered before the coronation, i.e. before 735. All reports of the first conquest of Ravenna by the Longobards - a second followed in 750/51 - ultimately go back to the sparse information in the history of the Longobard historian Paulus Diaconus . But with that the description of Andrea Dandolo also depends on Paul. The latter placed the coronation of Liutprand in the time when the coronation operators believed that King Hildeprand (who only died in 744) was dying (VI, 55). Paulus Diaconus, however, did not grant the newly crowned a large share of the royal power, and in connection with the loss of Ravenna he contrasted his capture with the manly ('viriliter') death of another defender of the city, a Vicentine . If one follows this logic, no more chronological conclusions can be drawn from the designation as a mere nepus . Ottorino Bertolini, who made clear the aforementioned chronic dependence on Paul, nevertheless also adhered to the Nepos chronology and in this way was even able to establish a temporal proximity to the dispatch of a fleet of Leo III. construct against the Italian insurgents, of which Theophanes in turn reports. Bertolini argued that this naval operation, the exact aim of which is not known, was directed against the Lombards.

As an argument in favor of dating the battle for Ravenna to the late 730s, Thomas Hodgkin cited positioning in the course of Paulus Deacon's text (VI, 54). It follows the Pope's request for help from the Frankish caretaker Karl Martell , which can be dated to 739. Added to this is the date by Johannes Diaconus to the time around 740. In fact, if one casts doubt on the traditional Venetian chronology, an argument for this temporal placement by Pope Gregory III's second letter. to Karl Martell to wear. Both letters from the Pope to the Franconian housekeeper can be found in the Codex epistolaris Carolinus , but without a date. The first letter can be dated to the summer of the year 739, so that it is usually assumed that the second letter in question was dated around the turn of the year 739 to 740. In the second letter, the Pope complains about the loss of what little is left in Ravenna to provide for the poor in Rome and for the church lighting in the Ravenna (“id, quod modicum remanserat preterito anno pro subsidio et alimento pauperum Christi seu luminariorum con-cinnatione in partibus Ravennacium ”). With reference to the previous year, all this has now been 'destroyed by sword and fire' (“nunc gladio et igni cuncta consumi”), namely by the Lombard kings Liutprand and Hildeprand. The reference to the previous year places the letter shortly after September 1, 739. Since there is no indication that the Lombards conquered Ravenna twice in these years, according to this timely source, the said conquest of Ravenna must fall in the autumn of 739. The Pope's letter to Antoninus von Grado, in which he asked the Venetians for help, was thus written at the same time as the second letter to Charles Martell.

Another argument against the earlier dating is that it was for Gregory III. there was no reason to speak out in such anger against the Lombards, who were allied at the time, and who had saved his predecessor from an attack by the Byzantine emperor's henchmen a few years earlier. In addition, Gregor expresses a strong expression of loyalty to the emperors in his letter, which would have been extremely unlikely in the chaotic situation around 732 ("ut zelo et amore sancte fidei nostre in statu rei publice et imperiali servicio firmi persistere"). At that time, the Pope even avoided dating the imperial reign, and his envoys were in Byzantine custody. But even at the beginning of 739 such a formulation would be surprising if, following the Chronicon Moissiacense , one assumes that the papal ambassadors asked Karl Martell for help "relicto imperatore Graecorum et dominatione, ad praedicti principis defensionem et invictam eius clementiam convertere cum voluissent", when they broke away from the Greek emperor and his rule. The rejection of the request by the Franks may have forced the Pope to look for a way to end the open rebellion against the emperor that began in the late 720s. This is also indicated by the fact that the Pope, in a letter to Boniface dated October 29, 739, resumed the imperial dating formula after many years. Gregor's successor also followed this more loyal line despite the ongoing dispute over image veneration. The open conflict with the emperor ended in the course of 739, the year in which Ravenna was also successfully retaken. The hope of Byzantine help, however, had long since vanished. This is already shown in a letter of Gregory II from 731 to Emperor Leo III. , in which he wrote to him, "He no longer has any hope of receiving help from them, 'because you cannot defend us at all!'"

Pietro Pinton had already suggested dating the Battle of Ravenna to 740 in 1883 (see above) and again in 1893. He saw the sequence of the reports of Paul the deacon as timely. This dating was adopted - also by Heinrich Kretschmayr in 1905 - by Roberto Cessi in 1963 , by Jadran Ferluga in 1991 and by Pierandrea Moro in 1997. Constantin Zuckerman placed the events around Ravenna in the larger context of the "dark centuries" of Byzantium and in 2005 came to the conclusion that the conquest by the Venetians must have taken place in autumn 739.

swell

- Greg. II Papa, Epistolae et Canones, ep. XII [at 730], PL 89, col. 519: “et ejectis magistratibus tuis, proprios constituere magistratus”; MGH Epp. III, Epistolae Lang. coll. No. 11f., p. 702.10-16. 26-32 (epp. Gregorii).

- Liber Pontificalis I 91, p. 405-409. 417, 429.10 ("Eutychius, excellentissimus patricius et exarchus").

- Chronicon Salernitanum , cap. 2, p. 4.13-15 (depending on the representation of the Liber Pontificalis).

- Paulus Diaconus , Historia gentis Langobardorum , ed. Ludwig Bethmann , Georg Waitz , in: Monumenta Germaniae Historica , Scriptores rerum Langobardicarum et Italicarum saec. VI – IX , Hahn, Hannover 1878, pp. 181, 19–22 (VI, 49) ( digitized version )

- John the Deacon , Cronaca Veneziana 95.7-13. 25f. (without naming names, just “Ravenne primas”).

- Ester Pastorello (Ed.): Andreae Danduli Ducis Venetiarum Chronica per extensum descripta aa. 46-1280 (= Rerum Italicarum Scriptores XII, 1), Nicola Zanichelli, Bologna 1938, pp. 112-114 ( digitized from p. 112 f. ).

literature

- Thomas S. Brown: Eutichio , in: Dizionario biografico degli Italiani 43 (1993) 551-554.

- Friedhelm Winkelmann u. a .: Prosopography of the Middle Byzantine period . 1. Department, Volume 1, De Gruyter Verlag, Berlin – New York 1998, pp. 588–589, No. 1870.

- Alexios G. Savvides, Benjamin Hendrickx (Eds.): Encyclopaedic Prosopographical Lexicon of Byzantine History and Civilization . Vol. 2: Baanes-Eznik of Kolb . Brepols Publishers, Turnhout 2008, ISBN 978-2-503-52377-4 , p. 451.

Remarks

- ↑ Greg. II Papa, Epistolae et Canones, ep. XII [at 730], PL 89, col. 519: "et ejectis magistratibus tuis, proprios constituere magistratus" (Georgio Arnosti: La crisi iconoclasta, l'ascesa di Venecia, ei suoi patti coi Longobardi , in: CENITA FELICITER L'epopea goto-romaico-longobarda nella Venetia tra VI e VIII sec. dC , in press ( academia.edu )).

- ↑ "Per idem tempus Leo augustus ad peiora progressus est, ita ut conpelleret omnes Constantinopolim habitantes tam vi quam blandimentis, ut deponerent ubicumque haberentes imagines tam Salvatoris quamque eius sanctae genetricis vel omnium incendio sanctoria." , Historia gentis Langobardorum , eds. Ludwig Bethmann , Georg Waitz , in: Monumenta Germaniae Historica , Scriptores rerum Langobardicarum et Italicarum saec. VI – IX . Hahn, Hanover 1878, p. 182 (6, 49) ( digitized version )).

- ↑ Christopher Kleinhenz (Ed.): Medieval Italy. An Encyclopedia , 2nd ed., Vol. II, Routledge, New York 2014, p. 949.

- ↑ Ester Pastorello (ed.): Andreae Danduli Ducis Venetiarum Chronica per extensum descripta aa. 46-1280 (= Rerum Italicarum Scriptores XII, 1), Nicola Zanichelli, Bologna 1938, pp. 112-114 ( digitized from p. 112 f. ).

- ↑ Marco Foscarini : Della letteratura veneziana, con aggiunte inedite dedicata al principe Andrea Giovanelli , reprint of the edition from 1732, Venice 1854, p. 105.

- ↑ Paulus Diaconus , Historia Langobardorum , ed. Ludwig Bethmann , Georg Waitz , in: Monumenta Germaniae Historica , Scriptores rerum Langobardicarum et Italicarum saec. VI-IX . Hahn, Hanover 1878, p. 183 f. (6, 54) ( digitized version )

- ↑ Ester Pastorello (ed.): Andreae Danduli Ducis Venetiarum Chronica per extensum descripta aa. 46-1280 (= Rerum Italicarum Scriptores XII, 1), Nicola Zanichelli, Bologna 1938, p. 113 ( digitized version ). There it says: “Dux autem, cum Venetis, zelo fidei accensi, cum navali exercitu, Ravenam properantes, urbem impugnant, et Yldeprandum nepotem regis capiunt, et Peredeo ducem vicentinum viriliter pugna [n] tem occidunt: et, optenta urbe, exarchum in sede restituunt. Que quidem Venetorum probitas et fides laudabilis, testimonio Pauli gestorum Langobardorum ystoriographi, conprobantur. "

- ^ Roberto Pesce (Ed.): Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo. Origini - 1362 , Centro di Studi Medievali e Rinascimentali "Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna", Venice 2010, p. 15 f.

- ↑ Pietro Marcello : Vite de'prencipi di Vinegia in the translation by Lodovico Domenichi, Marcolini, 1558, p. 3 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Heinrich Kellner : Chronica that is Warhaffte actual and short description, all life in Venice , Frankfurt 1574, p. 2r – 2v ( digitized, p. 2r ).

- ↑ Șerban V. Marin (Ed.): Gian Giacomo Caroldo. Istorii Veneţiene , vol. I: De la originile Cetăţii la moartea dogelui Giacopo Tiepolo (1249) , Arhivele Naţionale ale României, Bucharest 2008, p. 47 f. ( online ).

- ^ "Gregorio Vescovo, Servo de servi di Dio, al diletto figliuolo Orso Duce de Venetia. Perche la Città di Ravenna, la qual'era capo di tuttel'altre, cosi causando il peccato, è stata presa dall'indegna di esser pur nominata gente Longobarda; et il figiuol nostro prestantissimo, il Signor Essarcho, dimora (come havemo inteso) appressodi voi; debba la Nobiltà tua a quello adherirsi et conlui etiandio per nome nostro poner ogn'opera con tutte le forze, acciò quella Città sia ritornata nel pristino stato alla Republica et Imperial servitio delli Signori et figliuoli nostri Leone et'Imperator, con il zelo della Santa Fede nostra, possiamo, per gratia del Signore, perseverar intrepidamente per lo stato della Republica et Imperial servitio. Il Signor Dio ti conservi, carissimo figliuolo ”(p. 48).

- ↑ Bernardo Giustiniani: Historia di M. Bernardo Giustiniano gentilhuomo vinitiano dell'origine di Vinegia, & delle cose fatte da Vinitiani. Nella quale anchora ampiamente si contengono le guerre de 'Gotthi, de Longobardi, & de' Saraceni. Nuouamente tradotta da M. Lodouico Domenichi , Venice 1545 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Leslie Brubaker, John F. Haldon: Byzantium in the Iconoclast era. c. 680-850. A History , Cambridge University Press, 2011, especially pp. 151-155.

- ↑ Marco Guazzo: Cronica di M. Marco Guazzo dal principio del mondo sino a questi nostri tempi ne la quale ordinatatamente contiensi l'essere de gli huomini illustri antiqui, & moderni, le cose, & i fatti di eterna memoria degni, occorsi dal principio del mondo fino à questi nostri tempi , Francesco Bindoni, Venice 1553, f. 167v. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Francesco Sansovino : Cronologia del mondo di M. Sansouino Divisa in tre libri , Stamperia della Luna, Venice 1580, f. 42v, under the year 726 or "Anno del Mondo" 5925.

- ↑ Michele Zappullo: Sommario istorico , Gio: Giacomo Carlino & Costantino Vitale, Naples 1609, p. 316.

- ↑ Modo dell'elettione del serenissimo prencipe di Venetia. Con il nome, e cognome di tutti i prencipi, e con gli anni che ciascuno ha vissuto nel dogato, in Eraclia, in Malamocco, & in Rialto, fino al sereniss. Nicolo Contarini aggiunte alcune dichiarationi, tratte dalle Croniche, che nell'altre impressini non si leggeuano , Francesco Cavalli, Rome 1630, o. S. ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Alessandro Maria Vianoli : Der Venetianischen Herthaben life / government, and withering / from the first Paulutio Anafesto an / bit on the now-ruling Marcum Antonium Justiniani , Nuremberg 1686, p. 36-40 ( digitized ).

- ↑ Augustinus Valiero: Dell'utilità che si può ritrarre dalle cose operate dai veneziani libri XIV , Bettinelli, Padua 1787, p. 17 f.

- ↑ Johann Friedrich LeBret : State history of the Republic of Venice, from its origin to our times, in which the text of the abbot L'Augier is the basis, but its errors are corrected, the incidents are presented in a certain and from real sources, and after a Ordered the correct time order, at the same time adding new additions to the spirit of the Venetian laws and secular and ecclesiastical affairs, to the internal state constitution, its systematic changes and the development of the aristocratic government from one century to the next , 4 vols., Johann Friedrich Hartknoch , Riga and Leipzig 1769–1777, Vol. 1, Leipzig and Riga 1769, pp. 96–98 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Carlo Antonio Marin : Storia civile e politica del commercio de 'veniziani , 8 vols., Coleti, Venice 1798-1808, vol. 1, Venice 1798, p. 176.

- ^ Antonio Quadri : Otto giorni a Venezia , Molinari, 1824, 2nd ed., Part II, Francesco Andreola, Venice 1826, p. 60 f.

- ↑ Jacopo Filiasi : Memorie storiche de 'Veneti primi e secondi , vol. 5: Storia dei Veneti primi sotto il dominio dei Eruli e Goti , 2nd edition, Padua 1812, pp. 213-241.

- ^ Giovanni Bellomo: Lezioni di storia del medio evo , G. Antonelli, Venice 1852, p. 24 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Samuele Romanin : Storia documentata di Venezia , 10 vols., Pietro Naratovich, Venice 1853-1861, 2nd edition 1912-1921, reprint Venice 1972.

- ↑ Francesco Zanotto: Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia , Vol. 4, Venice 1861, pp. 8-10 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Adalbert Müller : Venice - His art treasures and historical memories. A guide in the city and on the neighboring islands , 1st edition, HF Münster, Venice / Triest / Verona 1857, p. 42.

- ↑ Giuseppe Cappelletti : Breve corso di storia di Venezia condotta sino ai nostri giorni a facile istruzione popolare , Grimaldo, Venice 1872, pp. 21-24.

- ↑ This is what Paul the deacon called him.

- ↑ Gianjacopo Fontana: Storia popolare di Venezia dalle origini sino ai tempi nostri , Vol 1, Giovanni Cecchini, Venice 1870, p.59..

- ↑ J. Billitzer: history of Venice from its inception up to the latest time f, coalfish, Trieste / Venice / Milan, 1871, p. 5

- ↑ August Friedrich Gfrörer: History of Venice from its foundation to the year 1084. Edited from his estate, supplemented and continued by Dr. JB Weiß , Graz 1872 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Pietro Pinton: La storia di Venezia di AF Gfrörer , in: Archivio Veneto (1883) 23–63 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Paulus Diaconus (VI, 49) says: "Liutprandus Ravennam obsedit, Classem invasit atque destruxit."

- ↑ This and the following according to Constantin Zuckerman: Learning from the Enemy and More: Studies in “Dark Centuries” Byzantium , in: Millennium 2 (2005) 79–135, esp. Pp. 85–94.

- ^ Ottorino Bertolini: Quale fu il vero obiettivo assegnato in Italia da Leone III "Isaurico" all'armata di Manes, stratego dei Cibyrreoti? , in: Byzantinische Forschungen 2 (1967) 40 f.

- ↑ Codex Carolinus 2, edited by Wilhelm Gundlach , in MGH Epp., III, p. 477.

- ↑ Chronicon Moissiacense, ed. By Georg Heinrich Pertz , MGH Scriptores I, Hannover 1826, p. 291 f.

- ↑ Quoted from: Stefan Weinfurter : Karl der Große. Der heilige Barbar , Piper, München und Zürich 2015, p. 84 and note 18 on p. 274, where the author cites as evidence: Migne, Patrologia Latina 89, Sp. 519, and he quotes from the letter: “cum tu nos defendere minime possis ”. It is about the Pope's Epistola XII, Sp. 511-521 ( reference in Sp. 519 ).

- ^ Pietro Pinton: Longobardi e veneziani a Ravenna. Nota critica sulle fonti , Balbi, Rome 1893, p. 30 f. and Ders .: Veneziani e Longobardi a Ravenna in: Archivio Veneto XXXVI11 (1889) 369-383 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Heinrich Kretschmayr : History of Venice , 3 vol., Vol. 1, Gotha 1905, p. 48.

- ^ Roberto Cessi: Venezia ducale , vol. I: Duca e popolo , Venice 1963, p. 103.

- ↑ Jadran Ferluga : L'esarcato , in: Antonio Carile (ed.): Storia di Ravenna , Vol. II / 1: Dall'età bizantina all'età ottoniana. Territorio, economia e società , Venice 1991, pp. 351–377, here: p. 371.

- ↑ Pierandrea Moro: Venezia e l'occidente nell'alto medioevo. Dal confine longobardo al pactum lotariano , in: Stefano Gasparri, Giovanni Levi, Pierandrea Moro (eds.): Venezia. Itinerari per la città , Il Mulino, Bologna 1997, p. 42.

- ↑ Constantin Zuckerman: Learning from the Enemy and More: Studies in “Dark Centuries” Byzantium , in: Millennium 2 (2005) 79–135, especially pp. 85–94.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Paul | Exarchs of Ravenna-Italy | --- |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Eutychius |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Eutychios |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Byzantine exarch of Ravenna |

| DATE OF BIRTH | before 727 |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 751 |