Dominicus Leo

According to the Venetian tradition, Dominicus Leo , also Domenico de'Leoni , was the first of the five magistri militum who, after the death of Doge Orso Ipato , in the years from 737 to 742, the settlements in the Venetian lagoon for ever Year ruled. Dominicus was the first of these magistri , if one follows this tradition, in office from 737 to 738. Neither the place of birth nor the place of death is known, nor the associated times. His successor was Felix Cornicula .

The government data of the first lords of the lagoon are generally uncertain, the historicity of the first two doges is even disputed. The dating convention is largely based on determinations that go back to the chronicle of Doge Andrea Dandolo , and thus to the more than half a millennium younger, state-controlled historiography of Venice. These wrote the essential services to the Doge, during the five years of the Magistri nebulous remained. More recent research can hardly classify these to this day, but has meanwhile largely freed itself from the Venetian tradition. The question of whether the short-lived office indicates a dominance of the Eastern Roman Empire in the lagoon , or, on the contrary, speaks for the rebellion of the dominant families in the lagoon, has long been discussed. The focus of the research is the reconquest of the Eastern Roman Ravenna from the Lombards by a Venetian fleet, which has now been postponed to the year 739 , which does not, as in the Venetian tradition, fall in the year 727 and thus during the reign of a Doge, but one of the Magistri militum .

Venetian historiography, which from the 14th century onwards was based predominantly on the work of Doge Andrea Dandolo, saw the battle for Ravenna as central against the background of the iconoclastic controversy and the “national resistance” of the Italians against Byzantine rule . This turned the Venetian naval operation into a turning point in the history of Venice, if not the Mediterranean. On the one hand, the Republic of Venice could be singled out as the savior of Eastern Byzantium and, at the same time, of the Pope, who was in conflict with the Byzantine iconoclasts. On the other hand, in the Byzantine Empire, the city received economic privileges and rule over the Adriatic for the first time - an orientation that already referred to Enrico Dandolo , under whose leadership the Byzantine capital Constantinople was conquered in 1204. In this way, the later historiography was able to make credible that the paths of domination that had been taken in the meantime already reached back to the early days of Venice, but also that only internal disputes could stop the Venetians, those disputes that led to the death of Orso and the establishment of the magistri militum had led, of which Dominicus Leo was the first.

Uncertain timing, reasons for the abolition of the Doge's office

As with his predecessors, Dominicus Leo’s information about his reign differed greatly for a long time. Marco Guazzo states in his cronica in 1553 that "Orso Ipato terzo doge di Venezia" was made doge in 721 and spent nine years in office. After Guazzo he drove the Heraclians into battle. The few survivors eventually turned against the Doge and killed him. After that, Venice was without a doge for six years (from 730 to 736) "reggendosi per altri magistrati, & uffici". The lagoon ruled itself through other magistrates and offices, by which the magistri militum were meant. In his Sommario istorico in 1609, Michele Zappullo sets the election year Orsos to 724 and the year of death to 729. Francesco Sansovino writes in 1580 in his Cronologia del mondo under the year 726 that Orso “died by the people”.

But when it came to dating, the uncertainty was greater than these comparatively close dates suggest. In 1687 Jacob von Sandrart wrote in his work Kurtze and an increased description of the origin / recording / territories / and government of the world-famous Venice Republic that “Horleus Ursus Hypatus” 726 had been “chosen”, but he added: The doge “chased away the Exarchum at Ravenna, but it became so dominant / that the people in the eleventh year of his reign revolted against him / and killed him. This is set by others in the 680th year. ”This uncertainty in the dating continued. In Volume 23 of the source series Rerum Italicarum Scriptores edited by Lodovico Antonio Muratori it is reported that Orso was elected in 711. In contrast, Samuel von Pufendorf (1632–1694) mentions the year 737 as the end of his reign.

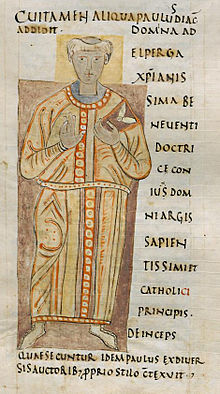

Not only the dating left room for speculation, but also the origin. Giovanni Pietro de'Crescenzi Romani states in his Corona della nobilta d'Italia , published in 1642, that “Domenico de'Leoni” came from a noble family from Padua and Rome .

Judgments about Dominicus Leo's administration, attempts to explain the transition to the Magistri

Until the end of the Republic of Venice (1797)

Heinrich Kellner explains in his Chronica , published in 1574, that this is the actual and brief description of all the people who live in Venice after useless battles: “In the end / when one person did a lot of damage to the other, the heart of the city was hewn to pieces by his own people . [...] And that was done in the eleventh year of his Hertzogthumbs. "In Malamocco, the parties to the dispute, so Kellner's laconic reasoning," then they had no desire to be involved / that is why they voted for a war colonel in the community / who took over the regiment and everyone Administration had / but one didn't wear this felch then a jar. The first was Dominicus Leoni / elected with a unanimous vote. "In the Historia Veneta by Alessandro Maria Vianoli from 1680, which was translated into German under the title Der Venetianischen Herthaben Leben / Government, und Absterben , Nürnberg 1686, the first master's name was" Dominicus Leoni ”and according to the translation his title was“ Master of Knighthood ”(p. 41 f.). Vianoli believes that the “Master” was “gifted with strange cleverness and wisdom” and that he “brought the Jesolans, when they approved of his righteousness, / and accepted the general peace offered / to complete rest. He succeeded Felix Cornicula in the following 738th year ”.

Orso was later accused of advocating Eraclea too unilaterally, with the result that the Doge was murdered in the course of the fighting after he had served in his post for eleven years and five months. According to Augustine Valiero, he was haughty and inclined to tyranny. Vincentius Briemle formulated this idea more drastically in his pilgrimage in 1727 : According to him it was the case that Ursus, "inflated by pride and arrogance, began to tyrannize tremendously, so the Pövel stood up against him and beat him to death in 737." Johann Heinrich Zedler writes in volume 14 of his Allgemeine Staats-, Kriegs-, Kirchen- und Schehrten -Chronicke of 1745, after Orso “because of his arrogance became unbearable to the people, he was murdered by the mob in 737, and another head, Maestro di Cavalieri or called Magister equitum, elected who received almost all power, like the doge, but with the change that every year a new maestro should be elected. ”In the meantime, the year 737 had prevailed for murder and taking office, but the title had been changed from Magister militum to Magister equitum . The cause of the overthrow is again sought in the person of the Doge, whose office was to be abolished, and at the same time the power of the new head was to be curbed by the annuity principle. The Magistri equitum also appear with this title in the 40th volume of Zedler's Great Complete Universal Lexicon of All Sciences and Arts , where Orso was "slain by the mob because of his unbearable bankruptcies". Johann Huebner's Kurtze questions from the Political Historia of 1710 remain even more laconic, but speaks of an “INTERREGNUM in Venice” after Orso “massacred”, an interregnum that lasted five years. This tendency to drop the magistri in the ranks of the rulers of Venice largely prevailed. At the same time, Marcellus , the second doge of the Venetian tradition, who is only mentioned as Magister militum in contemporary sources , had long since been added to the ranks of the doges without justification.

Attempts to classify national states: between civil war and Mediterranean great power politics

For Antonio Quadri, in the course of the fighting for Orso in 1826, the spirits were so whipped ("esasperato") that the "nazione", instead of electing a new Doge, resorted to the Magistri militum . Carlo Antonio Marin had considered this to be a clever move by the people's assembly to end the anarchy, because it gave power to a single Magister militum , if only for one year at a time.

Jacopo Filiasi believed in his Memorie storiche de 'Veneti in 1812 that Orso had cracked down on the Equilians, and even demanded a tribute from them. Therefore, there were fights that developed into a civil war, as Dandolo had already noted, the Filiasi quotes ("Civilibus bellis exortis, nequiter occisus est"), but without specifying the exact location. Filiasi suspects that the people may also have revolted against absolute rule by the Doge, and that the office was therefore abolished.

Orso and with it the role of the Magistri within the framework of the nation state was reinterpreted even more . In his Breve corso di storia di Venezia of 1872, dedicated to popular education , Giuseppe Cappelletti said that the proximity of the Lombards threatened Venetian “freedom” and “national riches” (“nazionali ricchezze”). Regarding the temporal classification, Cappelletti admits that the reconquest of Ravenna from the Lombards took place sometime between 726 and 735. But now the envy and hatred that ruled between the islands of the lagoon, as well as the private animosities between the tribunician families, but also the competition between Eraclea and Equilio had led to civil war. In the year 737, the lagoon inhabitants finally murdered the Orso, which was so well-deserved for the fame and honor of the nation, because they did not want to tolerate a doge over them.

August Friedrich Gfrörer († 1861) saw completely different causes in his History of Venice, which was published posthumously in 1872, from its founding to 1084 . According to him, the Longobard king Liutprand had offered the Byzantine exarch to reinstate him in Ravenna in order to then make common cause against Byzantium. According to his opinion, the exarch "Eutychius and Orso [...] must have been won ..." (p. 54). However, the Pope had dissuaded the Lombards from his plan (p. 55). Then Gfrörer continues: “One thing is certain: Duke Orso fell as a victim of Byzantine vengeance. In order to ensure its sovereignty over Veneto during the difficult times, the basileus on the Bosporus, after Orso had been overthrown by an instigated conspiracy, abolished the civil administration of the dukes and introduced a purely military government ”(p. 57). Consequently, the Magistri militum , who followed Ursus, were Gfrörer as a mere "colonel of war appointed by the imperial court at Constantinople". Dominicus Leo ruled until 738, followed by Felix Cornicula , who brought Deusdedit back. Andrea Dandolo believed that this was done for the purpose of reconciliation, and for this reason, and in order to redress the injustice to the father, Deusdedit himself was promoted to master's degree. As Gfrörer assumes on the Byzantine initiative, Jovianus followed him again - once again the title hypatus - was followed by John Fabriciacus in 741 , who was blinded in 742 (p. 59).

After the posthumous editor Dr. Johann Baptist von Weiß had forbidden the Italian translator Pietro Pinton to annotate Gfrörer's statements in the translation, Pinton's Italian version appeared in the Archivio Veneto . Pinton's own illustration did not appear in the Archivio Veneto until 1883. Orso, since Gfrörer's chronology contradicts the sources, was not overthrown by Byzantine intrigues, but by an internal Venetian civil war, as described in Andrea Dandolo's Chronicon breve . Pinton himself assumed that the reconquest of Ravenna did not take place until around 740 (pp. 40–42).

Modern research

The question of which side the first Magister militum is to be seen on, the Byzantine or the “autonomist” side, remains open to this day . Until recently, research assumed a revolt by the Venetian ruling class in 726/727, which in the end was no longer willing to submit to a Dux who no longer had any significant support from the exarch. Accordingly, argued Agostino Pertusi in 1964 , the annually changing magistri militum could be interpreted as the result of the growing ambitions of the groups prevailing in Venice, whereas the restoration of the Dogat could be interpreted as an increase in the Byzantine central power at the expense of the local ruling class. However, since Deusdedit was to be regarded as an exponent of Malamocco and no longer of the old headquarters of Heraclea, it was assumed, in contrast, that the group of families ruling in Malamocco had simply prevailed against those of Heraclea. Accordingly, with the murder of Orso, on the contrary, the Byzantine central power first returned in the form of the Magistri militum , against which Malamocco then resisted, as Gherardo Ortalli argued. The settlement of the epithet or title of Iubianus as Hypatus could therefore be based on a proximity to Byzantine power. It is unclear whether the aforementioned Magistri between Orso and Deusdedit had Venetian roots.

The classification of the reconquest of Ravenna in the time of the Magistri militum

The implied confusion regarding the dating of the battles for Ravenna found its way into modern historiography because of a single word in the description of the events by Paulus Deacon . This is the name of the Lombard king's nephew in connection with the battle for Ravenna as regis nepus . This was stated in 2005 by Constantin Zuckerman. Ludo Moritz Hartmann was of the opinion that Hildeprand , the nephew of the Lombard king Liutprand , who had been in office since 712 , would hardly have been addressed as nepus if he had already been king at the time of the battle for Ravenna. Since it can be deduced from Longobard sources that Hildeprand became king in the summer of 735, according to Hartmann, Ravenna must have been conquered before the coronation, i.e. before 735.

All reports of the first conquest of Ravenna by the Lombards - a second took place in 750/51 - ultimately go back to the sparse information in the historical work of the Lombard historian Paulus Diaconus, namely his Historia gentis Langobardorum . Paul placed the coronation of Hildeprand at the time when the coronation operators believed that King Liutprand (who only died in 744) was dying (VI, 55). It is true that the king's nephew was promoted to king himself, but Paulus Diaconus did not give the newly crowned man a large share of the royal power. On the contrary, in connection with the loss of Ravenna, he contrasted his capture with the manly ('viriliter') death of another defender of the city. If one follows this logic, then no more compelling chronological conclusions can be drawn from the designation as a mere nepus . Ottorino Bertolini, although he made clear the chronic dependence of Andrea Dandolo on Paulus Diaconus, nevertheless also stuck to the Nepos chronology, although a later dating of the battle for Ravenna, this time in the year 740, already Pietro Pinton in 1883 and again ten years later suggested. He saw the sequence of the accounts of Paul the deacon as chronologically correct. Constantin Zuckerman arranged the events of the reconquest of Ravenna from the Lombards in the larger context of the "dark centuries" of Byzantium and came to the conclusion in 2005 that the conquest by the Venetians must have taken place in autumn 739, and thus at the time of the second Magister militum .

swell

- Luigi Andrea Berto (ed.): Giovanni Diacono, Istoria Veneticorum (= Fonti per la Storia dell'Italia medievale. Storici italiani dal Cinquecento al Millecinquecento ad uso delle scuole, 2), Zanichelli, Bologna 1999 ( text edition based on Berto in the Archivio della Latinità Italiana del Medioevo (ALIM) from the University of Siena).

- La cronaca veneziana del diacono Giovanni , in: Giovanni Monticolo (ed.): Cronache veneziane antichissime (= Fonti per la storia d'Italia [Medio Evo], IX), Rome 1890, p. 95 ( digitized , PDF).

- Ester Pastorello (Ed.): Andrea Dandolo, Chronica per extensum descripta aa. 460-1280 dC , (= Rerum Italicarum Scriptores XII, 1), Nicola Zanichelli, Bologna 1938, p. 114 f. ( Digitized p. 114 f. )

Web links

- Giorgio Ravegnani: La nascita di Venezia, narrazioni, miti, legend. Venezia dalle origini alla Quarta Crociata , website of the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana

Remarks

- ↑ Marco Guazzo: Cronica di M. Marco Guazzo dal principio del mondo sino a questi nostri tempi ne la quale ordinatatamente contiensi l'essere de gli huomini illustri antiqui, & moderni, le cose, & i fatti di eterna memoria degni, occorsi dal principio del mondo fino à questi nostri tempi , Francesco Bindoni, Venice 1553, f. 167v. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Michele Zappullo: Sommario istorico , Gio: Giacomo Carlino & Costantino Vitale, Naples 1609, p. 316.

- ↑ Francesco Sansovino: Cronologia del mondo di M. Sansouino Divisa in tre libri , Stamperia della Luna, Venice 1580, f. 42v, under the year 726 or "Anno del Mondo" 5925.

- ↑ Jakob von Sandrart: Kurtze and increased description of the origin / recording / areas / and government of the world famous Republick Venice , Nuremberg 1687, p. 12 ( digitized, p. 12 ).

- ^ RIS, vol. 23, Milan 1733, col. 934.

- ^ Samuel von Pufendorf: Introduction à l'histoire générale et politique de l'Univers , Vol. 2, Chaterlain, Amsterdam 1732, p. 67.

- ↑ Giovanni Pietro de'Crescenzi Romani: Corona della Nobilta d'Italia overo compendio dell'istorie delle famiglie illustri , part 2, Nicolo Tebaldini, Bologna 1642, p 86 ( digitized ).

- ↑ Heinrich Kellner : Chronica that is Warhaffte actual and short description, all life in Venice , Frankfurt 1574, p. 2r – v ( digitized, p. 2r ).

- ↑ Alessandro Maria Vianoli: Historia veneta di Alessandro Maria Vianoli nobile veneto , Giacomo Herzt, Venice 1680, p. 36 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Alessandro Maria Vianoli : Der Venetianischen Herthaben life / government, and withering / from the first Paulutio Anafesto to / bit on the now-ruling Marcum Antonium Justiniani , Nuremberg 1686, translation ( digitized ).

- ↑ Augustinus Valiero: Dell'utilità che si può ritrarre dalle cose operate dai veneziani libri XIV , Bettinelli, Padua 1787, p. 20.

- ↑ Vincentius Briemle, Johann Josef Pock: The through the three parts of the world, Europe, Asia and Africa, especially in the same to Loreto, Rome, Monte-Cassino, no less Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Nazareth, Mount Sinai, [et] c. [Etc. and other holy places of the promised land employed devotional pilgrimage , first part: The journey from Munich through whole Welschland and back again , Georg Christoph Weber, Munich 1727, p. 188 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Johann Heinrich Zedler: General State, War, Church and Scholars Chronicke , Vol. 14, Leipzig 1745, p. 5 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Large complete Universal Lexicon of all sciences and arts , Vol. 46, Leipzig / Halle 1745, Sp. 1196 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Quoted from the 1714 edition: Johann Hübner: Kurtze Questions from the Political Historia , Part 3, new edition, Gleditsch and Son, 1714, p. 574 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Antonio Quadri: Otto giorni a Venezia , Molinari, 1824, 2nd ed., Part II, Francesco Andreola, Venice 1826, p. 60 f.

- ^ Carlo Antonio Marin : Storia civile e politica del commercio de 'veniziani , 8 vols., Coleti, Venice 1798-1808, vol. 1, Venice 1798, p. 182 f.

- ↑ Jacopo Filiasi : Memorie storiche de 'Veneti primi e secondi , vol. 5: Storia dei Veneti primi sotto il dominio dei Eruli e Goti , 2nd edition, Padua 1812, pp. 213-241.

- ↑ Giuseppe Cappelletti: Breve corso di storia di Venezia condotta sino ai nostri giorni a facile istruzione popolare , Grimaldo, Venice 1872, pp. 21-24.

- ↑ August Friedrich Gfrörer : History of Venice from its foundation to the year 1084. Edited from his estate, supplemented and continued by Dr. JB Weiß , Graz 1872, ( digitized version ).

- ^ Pietro Pinton: La storia di Venezia di AF Gfrörer , in: Archivio Veneto (1883) 23–63 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ "Il ritorno di nuovo ai duces ... è da intendere come un ritorno alla normalità, cioè alla sovranità bizantina dell'esarco." (Agostino Pertusi: L'impero bizantino e l'evolversi dei suoi interessi nell'alto Adriatico , in : Le origini di Venezia , Florence 1964, p. 69).

- ↑ "il trasferimento della sede a Malamocco […] die ad indicare una ripresa del processo autonomistico" (Gherardo Ortalli: Venezia dalle origini a Pietro II Orseolo , in: Longobardi e Bizantini , Turin 1980, pp. 339-428, here: p . 367).

- ↑ This and the following according to Constantin Zuckerman: Learning from the Enemy and More: Studies in “Dark Centuries” Byzantium , in: Millennium 2 (2005) 79–135, esp. Pp. 85–94.

- ^ Ottorino Bertolini: Quale fu il vero obiettivo assegnato in Italia da Leone III "Isaurico" all'armata di Manes, stratego dei Cibyrreoti? , in: Byzantinische Forschungen 2 (1967) 40 f.

- ^ Pietro Pinton: Longobardi e veneziani a Ravenna. Nota critica sulle fonti , Balbi, Rome 1893, p. 30 f. and Ders .: Veneziani e Longobardi a Ravenna in: Archivio Veneto XXXVI11 (1889) 369-383 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Constantin Zuckerman: Learning from the Enemy and More: Studies in “Dark Centuries” Byzantium , in: Millennium 2 (2005) 79–135, especially pp. 85–94.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Dominicus Leo |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Magister militum of Venice |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 7th century or 8th century |

| DATE OF DEATH | 8th century |