Oriental schism

The Oriental Schism , also called Great Schism (Greek: Σχίσμα Λατίνων , "Latin Schism"; Latin : Schisma Graecorum , "Greek Schism") is the schism between the Orthodox Churches and the Roman Catholic Church . The term “Oriental Schism” is a polemical term used by the West. From an Eastern perspective, the West has split off by disregarding the motto of Vincent von Lérins , that "everything is believed by everyone everywhere, always," and arbitrarily added the Filioque to the Church's creed of Nicaea and Constantinople .

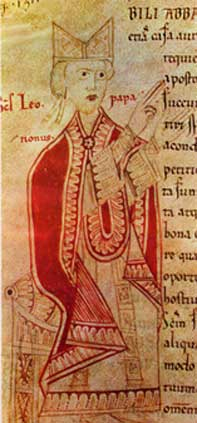

The year 1054 is commonly given as the date for the schism , when Humbert de Silva Candida , the envoy of Pope Leo IX. , and Patriarch Michael I of Constantinople excommunicated each other after failed union negotiations . However, this is historically incorrect, because with the death of the Pope and Patriarch, the ban was over . In fact, the Pope was still temporarily commemorated in the Orthodox liturgy .

Emotionally, the relationship between Rome and Constantinople was damaged primarily by the events of the Fourth Crusade , when Constantinople was captured and sacked by the Venetians in 1204 and a Latin empire and a Latin patriarch were established. Historians today agree that the churches parted because of a progressive alienation that coincided with the growth of papal authority. Decisive for the separation were not theological differences, but ecclesiastical political factors. The final separation took place römischerseits until 1729, when the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith ( de Propaganda Fide Congregation ) the Sacrament community ( communicatio in sacris ) banned by the Orthodox. In 1755, the Orthodox Patriarchs of Alexandria , Jerusalem and Constantinople declared the Catholics false teachers in return . The Patriarchate of Antioch later joined, but not that of Moscow . This declaration has not been withdrawn by the Orthodox side until today, whereas the mutual banishment of 1054 during the Second Vatican Council by Pope Paul VI. and the Ecumenical Patriarch Athinagoras on December 7, 1965 at the same time in Rome and Istanbul in a solemn form "was erased from the memory and from the center of the Church" and should "fall into oblivion".

Alienation between East and West

language

At the beginning of alienation simply was the fact that it was becoming less common during the early centuries in Rome and generally in the West, the Greek language to master, which for centuries around the whole Mediterranean lingua franca ( common language had been). Theological exchange also diminished in the Church. As early as the fourth century there were only a few western church fathers who spoke Greek ( Ambrosius of Milan , Hieronymus ) - but the leading church teacher among the Latin speakers, Augustine of Hippo , was not one of them. Even the highly educated Gregory I the Great , ambassador to Constantinople in the 6th century, did not speak any Greek. Conversely, the works of Augustine were not translated into Greek until the 14th century. In general, the Greek patriarchs did not speak Latin. The philologist Photios , for example, spurned learning this “barbaric” language. So you always had to rely on translators, secretaries, and experts when dealing with one another.

The mass was held in Latin instead of Greek from 380 (Pope Damasus I ).

Culture

Another aspect are cultural differences, different spiritual values and attitudes. Greeks viewed Romans as uneducated and barbaric, while Romans viewed Greeks as snooty and subtle.

The Church Fathers' education and professional background also differed:

- Many leading theologians in the West had the legal and political education that was customary in Roman culture: Tertullian , Ambrosius of Milan , Augustine . Therefore the legal aspects ( doctrine of justification ) and the organizational aspects ( ecclesiology ) were particularly important to them in theology .

- In the East, on the other hand, classical education, including classical philosophy , rhetoric , and natural sciences ( Origen , Basil of Caesarea , Gregory of Nazianz ) predominated . That is why theology was more about fundamental philosophical questions such as Christology .

The heresies , which cause the most problems, also deal with parallel questions: with Donatism in the West primarily about canon law, with Arianism and Monophysitism in the East about christological questions and the relationship of faith to secular philosophy.

In the East there were traditionally numerous educated lay people who took an active part in church life and in theology , and some of them (for example Photius ) made it to the status of patriarch. In the West, due to political developments, the church had an educational monopoly from around the late 5th century - all future clergy could only get their training within the church, lay people were only very rarely educated at all.

Political development

The relocation of the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome to Constantinople in 330, and in particular the fall of Western Rome , resulted in very different political constellations: In the east there was the emperor as the center of political power and in the church there were several patriarchs of equal rank, one of them neither had authority over the others.

For centuries there was no central political power in the West, only arguing local princes and an ecclesiastical patriarch (the Roman Pope), who was the only one able to guarantee stability and continuity and thus became a central authority - and who also emerged from this situation had to be politically active towards the local princes.

The political element in the understanding of ministry was reinforced when the Pope by the Frankish king Pippin to the secular lord of the Papal States was made and the fact more and saw more in the role of a secular ruler.

When in the west Pippin's son Charlemagne on December 25, 800 by Leo III. was crowned emperor because both saw the Byzantine imperial throne as vacant during the reign of Irene , it was another break with the east. The Greeks, politicians and clerics as well as ordinary citizens were appalled that the Roman bishop arbitrarily crowned a “barbarian prince” as Roman emperor, as if the Roman emperor no longer existed in Constantinople - in their opinion that was a betrayal of the state and the church.

theology

Theology soon developed different emphases on both sides, which at first fertilized each other, but then contributed to alienation because of the lesser exchange.

In the case of the Trinity , the East emphasized the three persons - including the Holy Spirit - while the West emphasized unity and placed the Holy Spirit in the second tier.

In the West, Augustine developed the dogma of original sin , according to which every human being is infected by Adam's guilt from conception and is legally guilty (which subsequently makes the immaculate conception of Mary necessary) - the East sees original sin in the consequences of Adam's guilt: Death, desire and the human tendency to sin.

This also gives rise to a different view of salvation: in the West it is primarily about the legal acquittal that Jesus brought about by taking the punishment for human sin - in the East, the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ bring about freedom from death and sin through which man can become godlike again and live with God forever. The western church saw Christ as the sacrifice, the eastern church saw Christ as the victor.

The Nicene Creed was given the addition of Filioque in the western church , while in the eastern church it remained in its original form. This specific conflict could no longer be interpreted as complementing each other.

Significance of the office of bishop : In the east there were many local churches that could refer to the foundation by an apostle - therefore all bishops were in principle regarded as having equal rights. Generally valid decisions could only be made through an ecumenical council , which also had to find general approval among the people. In the West, on the other hand, only the Roman Church could appeal to apostles, and this gave the Bishop of Rome a special position. The Eastern churches, which had always traditionally given the Bishop of Rome priority, had no problem with this monarchical attitude as long as it was limited to the West, i.e. to the Roman patriarchate. However, the Bishop of Rome came to believe that his authority extended not only to the West, but to the entire Church - and when the bishops of the East suddenly saw themselves in the role of those taking orders from Rome, they asked back which council decided that, which in turn was viewed in the West as an irrelevant issue. Here, too, there had been a development where views were mutually exclusive.

In addition, there had also been different developments in less essential matters: in the east married people could become priests, the west insisted on celibacy ; there were different rules regarding fasting , in the west unleavened bread was used for the Eucharist , in the east leavened bread .

Development of the Schism

Photios schism

By the middle of the 9th century, despite all these differences, the Eastern and Western Churches were in full communion with one another.

The first serious conflict occurred in 857. Emperor Michael III. had deposed the patriarch Ignatios I and the theologian Photios took his place . At a council in Constantinople in 861, Photios was recognized, also by the Pope's legates. Pope Nicholas I , however, convened a second council in Rome in 863, which deposed Photios, and conveyed this decision in the tone of an absolute ruler to Constantinople, where it was ignored by the patriarch and the emperor.

Photios was very involved in the Slav mission - he sent Cyril and his brother Methodius , the two Slav apostles , to Moravia. The conflict between him and Rome arose when Pope Nicholas I supported Frankish missionaries in Moravia who taught the creed with the filioque introduced in Spain - so far Rome had been neutral or even against the filioque question. Photios, a brilliant theologian, countered with a sharp encyclical and convened a council in Constantinople, where Nicholas was excommunicated.

In 867 Nikolaus died and Photios was deposed. In the fourth Council of Constantinople the deposition was confirmed and it was decided that Bulgaria would join the Patriarchate of Constantinople. This council was only declared an “Ecumenical Council” much later for political reasons in the West; in the East it is not recognized as such.

In 879, at another council in Constantinople, Photios was fully rehabilitated and there was a complete reconciliation between Rome ( John VIII ) and Constantinople (again Photios), with the Pope, who was not a friend of the Franks, in a private letter Photios is said to have declared that the Filioque was never in use in Rome and that it was heresy ; the authenticity of this letter is, however, disputed; important researchers such as B. Philip Schaff reject them. At this council, as a wise compromise, the traditional Roman primacy was recognized for the West, but any papal jurisdiction was rejected for the East.

Schism of 1054

The next serious conflict arose when the Normans conquered the previously Byzantine and largely Greek-speaking southern Italy over a period of several decades in the 11th century . Pope Leo IX promised help to the Byzantine governor of the province, on condition that the previously eastern churches in this area should adopt the western rite (in order to enforce the jurisdiction of Rome de facto there), i.e. unleavened bread in the Eucharist, Latin language in the liturgy and the creed with filioque. The governor agreed, the clergy in no way. Michael Kerullarios , the Patriarch of Constantinople, for his part ordered the Byzantine rite for the Latin churches in Constantinople (which were mainly visited by the local western envoys, traders etc.), and when they also resisted, he had the churches closed.

Cardinal Humbert von Silva Candida , a militant advocate of church reforms of the eleventh century and leading theoretician of the pope's jurisdictional supremacy, was sent to Constantinople as an envoy to resolve the conflict. As legitimation, Humbert submitted a letter (actually written by himself) in which "the Pope" declared that he had jurisdiction over the Patriarch of Constantinople. He denied the title of ecumenical patriarch, questioned the validity of his ordination , insulted a monk who defended Eastern customs, saying that he had come from a brothel , and demanded the correction of several "errors" in the Eastern Church, which Rome had neglected for too long - and when he understandably did not make progress with the negotiations, on July 16, 1054, in a fit of "righteous anger" , Humbert placed a bull with the excommunication of Kerullario and other Orthodox clergy on the altar of Hagia Sophia . In this bull the Orthodox Church is referred to as the "source of all heresies" and Kerullarios was ironically charged, among other things, with removing the Filioque from the creed (the Eastern Church was thus charged with altering the Creed that was actually adopted by the Western Church had been changed). As a result, Humbert demanded that the emperor and the clergy should immediately remove the "errors" listed, which led to the fact that he was almost lynched by the population and had to be taken into protective custody by the emperor.

After Humbert's immediate departure, he and his companions were in turn excommunicated by Kerullarios and a council (Pope Leo IX, who was also to be condemned, had already died at this point, so that the excommunication no longer affected him). The remaining Eastern Patriarchs clearly sided with Constantinople and also rejected Rome's claims.

Various assessments of the event of 1054 shape the picture in historical research:

a) Today the break of 1054 is often downplayed as possible and it is said that it was not the churches that excommunicated each other, but only individuals. At that time it was a break: from then on the Pope's name was no longer mentioned in the Byzantine liturgy and the churches in Constantinople remained closed for Latin rites.

b) The event of 1054 was only one piece of the mosaic in a development that spanned decades to centuries. Already before 1054 there had been a break between the Eastern and Western Churches:

- allegedly at the establishment of the East Franconian-German Empire by Otto I (962),

- then with the “Schism of the Two Sergioi”, Pope Sergius IV (1009-1012) and Patriarch Sergios II (1001-1019), in the years 1011/1012.

In the decades that followed, the churches faced each other without close ties, while in the decades after 1054 the alienation between the two Christian churches increased.

Efforts to reach agreement failed for several reasons, including in particular:

- the primacy of the reform papacy

- the opposition of the Constantinople Church

- the Norman policy in southern Italy against Byzantium

- the first crusade (1096-1099)

- as a result, the politico-military penetration of western Christianity into the Orient.

The ecclesiastical, dogmatic and liturgical differences (Filioque, Azymon ), which played a role in the power-political conflict between Pope and Patriarch before 1054, now came fully to light, and the event of 1054 now acquired a different, greater significance in retrospect.

Sack of Constantinople

On the Fourth Crusade (the so-called Venetian Crusade) Constantinople was conquered in 1204 and looted for three days - even the churches. Most of the numerous relics were shipped to the west. The Byzantine emperor was expelled and replaced for a few decades by a family of German-born petty princes as emperors by the grace of the Pope and Venice , the Greek church hierarchy by a parallel structured Latin hierarchy . Greek clergymen were forced to take an oath of obedience to Rome. Byzantine culture gradually formed anew in several empires in exile in Asia Minor.

From this point on, the separation between Eastern and Western Churches was no longer just a question of theologians and church politicians, but a tangible reality for the entire people of the Eastern Church.

Union aspirations since the High Middle Ages

At the second council of Lyon in 1274 and the council of Florence in 1439 an attempt was made to bring about a unification of the Eastern and Western Churches. This agreement was welcomed by the Byzantine emperors because of the " Turkish threat ". 1274 threatened an attack by Charles of Anjou , who had been crowned King of Sicily in 1266 . The people of the church and most of the church hierarchy were decidedly against it and saw it as a total surrender to Rome - which Rome certainly intended, although there were also some theologians in the West willing to compromise. The schism was not eliminated by these attempts at unification, but in the end actually intensified.

From the 16th century onwards, a policy of “ unions ” was cultivated from Rome , whereby, for various reasons, dissatisfied groups within the individual Eastern Churches were persuaded by Western ambassadors to recognize the Pope and to renounce their respective mother churches; they were allowed to maintain their own liturgy and customs by and large. This “ divide-and-rule ” strategy naturally led to great anger and strife among the other members and the leaderships of the Eastern Churches, who perceived the papal ambassadors not as unites but as divisors. Some leaders of the Eastern Church made an attempt to fraternize with the newly formed Protestants, but this was sharply criticized by the other Eastern clergy.

It took more than 500 years before a new understanding was reached between the Roman Catholic and the Eastern churches. On December 7, 1965, at the end of the Second Vatican Council , Pope Paul VI. and Patriarch Athinagoras on mutual excommunication.

The theological differences regarding rites and liturgical forms, which played an important role from the 11th to the 14th centuries, are now seen as largely overcome on both sides, but serious obstacles to further rapprochement are still today:

- the question of the Roman primacy

- the disagreement over the fate of the United Churches

- the still strong resentment and prejudice, some of which are based on ignorance

- the (re-) establishment of ecclesiastical structures by the Roman Catholic Church on the canonical territory of Orthodox Churches, especially in Russia

- the repeated accusation of proselytism or uniatism , especially by the Russian Orthodox, to the Roman Catholic Church, which particularly affects the activities of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in Ukraine .

But note: Declaration of Balamand .

literature

- Axel Bayer: Division of Christianity. The so-called Morgenländische Schisma of 1054 (= Archive for Cultural History. Supplement 53), 2nd edition. Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 2004, ISBN 3-412-03202-6 .

- Henry Chadwick : East and West. The Making of a Rift in the Church. From Apostolic Times until the Council of Florence (= Oxford History of the Christian Church ) Oxford University Press, Oxford u. a. 2003, ISBN 0-19-926457-0 .

- Colin Morris: The Papal Monarchy. The Western Church from 1050 to 1250 (= Oxford History of the Christian Church ) Clarendon Press, Oxford 1989, ISBN 0-19-826907-2 .

- Theodor Nikolaou (ed.): The schism between Eastern and Western Churches. 950 or 800 years later (1054 and 1204) (= contributions from the Center for Ecumenical Research Munich , Volume 2). Lit, Münster 2004, ISBN 3-8258-7914-3 .

- Walter Norden : The Papacy and Byzantium. The separation of the two powers and the problem of their reunification until the fall of the Byzantine Empire (1453). Behr, Berlin 1903, DNB 575264500 , OCLC 16749161 .

Press

- Axel Bayer: The Constantinople Catastrophe . Rheinischer Merkur , July 8, 2004.

Web links

- Ernst Christoph Suttner: The legend of the schism between East and West in the year 1054. In: Church in a world moving towards one another. Würzburg, 2003 (reproduced on the website of the Regensburg Eastern Church Institute).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Philip Schaff: History of the Christian Church, Chapter 5: The Conflict of the Eastern and Western Churches and Their Separation. Logos Research Systems, Oak Harbor, 1997, accessed August 9, 2017 (reproduced from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library).