Vitale Michiel I.

Vitale Michiel I († 1102 ) ruled from 1096 to 1102 as Doge of Venice . According to the historiographical tradition, as the state-controlled historiography of the Republic of Venice is called, he was its 33rd doge.

A Venetian fleet operated in the Holy Land for the first time from 1099 to 1100 . As a reward for the support of the crusaders, Venice received far-reaching trade privileges there, similar to that in the Byzantine Empire since 1082 and in the Roman-German Empire since 1095 . The robbery of relics , above all those of St. Nicholas of Myra , the Venetians, like many other crusaders . In the battle for Ferrara , Venice gained further privileges, but this also resulted in long-lasting conflicts with the Papal States and the ruling house of the Estonians of Ferrara.

family

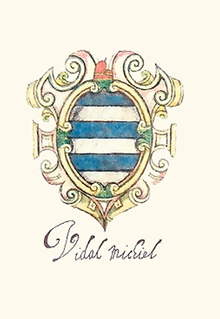

The Michiel family belonged to the so-called twelve apostolic case vecchie , the 'old houses'. Vitale Michiel was the first doge from the family, who provided two other doges as well as twelve procurators and a dogaressa - Taddea Michiel, the wife of Doge Giovanni Mocenigo . Vitale was married to a woman from the Corner House .

The Doge's Office

In 1095, a year after Vitale Michiel's enthronement, Pope Urban II called on Christianity to crusade against the “infidels” in order to free Jerusalem from the hands of the Turks. Venice did not respond to the Pope's ardent appeal.

However, when it was noticed that the competitors Genoa and Pisa were rewarded for their participation with privileges in the Levant and that disadvantages for the Mediterranean trade were feared, the Venetians equipped a fleet of 207 ships. She set sail in July 1099 under the leadership of the Doge's son Giovanni Michiel and the Bishop of Olivolo, Enrico Contarini, also the son of a Doge. In the first combat action of the fleet, however, the true interests of Venice soon became apparent: The Pisans lying off Rhodes were attacked and lost half of their ships in the sea battle, hundreds of Pisans were captured and the freedmen had to promise not to trade with Byzantium; Venice enjoyed extensive trading privileges there from 1082. In the Kingdom of Jerusalem , the conflicts between Venice and Pisa, and soon also Genoa , primarily affected the trade hub of Acre .

After wintering in Rhodes , they sailed towards Jerusalem, which was conquered in 1099 under the leadership of Godfrey of Bouillon . Due to the failure of the Pisan fleet, however, there were problems with the food supply, the troop supplies and the control of the conquered coastal strip. Therefore, Gottfried was forced to negotiate with the Venetians. They received extremely valuable consideration for their help, such as a separate, tax-exempt city district and important trade privileges.

According to legend, the Venetian crusaders - in Myra or Bari - seized the bones of St. Nikolaus von Myra , the patron saint of seafarers. The church of San Nicolò was built for these relics after the return of the fleet on the Lido . Large-scale procurement of relics was part of politics and, in addition to religious purposes, served to upgrade the city as a pilgrimage destination.

The support of Margravine Mathilde of Tuszien in the conquest of Ferrara was also rewarded with trade privileges, which, however, led to tensions between Venice and the Estonians and the Papal States. In the same year 1101 a contract was signed with Imola , which facilitated the trade in grain from the Marche .

Vitale Michiel, about whose domestic politics nothing is known, died in the spring of 1102. He was buried in the atrium of San Marco .

reception

Until the end of the Republic of Venice

The Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo from the late 14th century, which laconically reports in the case of this Doge and is the oldest vernacular chronicle of Venice, presents the events as well as the Chronicle of Andrea Dandolo on a long-familiar at that time, largely dominated by the Doges Level - they even form the temporal framework for the entire chronicle. This also applies to “Vidal Michael”, who succeeded his predecessor “Vidal Falier”, who died in “Giara”, in office. In his time an "armada grande in subscidio dele Terre Sancte de Egipto" was sent, one of which was "capetanio" "Henrigo Contharin vescovo de Venesia". The Bishop of Venice led one fleet to the Holy Land, the other was the son of Doge Domenico I. Contarini . In the "contrada de Jerusalem", in the Kingdom of Jerusalem , he took a strong fort called "Garpha", which was given to those of Acre "per la franchisia et ruga che li Venetiani avea in Suria". For this he received privileges and "gratie" from King Baldwin I. The fleet leader continued his journey towards “Smire” and, “como io trovo in una cronica” ('as I find in a chronicle'), he took the relics of St. Nikolaus per se ("tolse"), while others say he took them from "Pathrax" in "Romania bassa". Or maybe the saint's arm came from Bari . The relic “fu collochado” in the year “MLXXXXVI” in San Nicolò di Lido . The Doge was killed by a Marco Cassolo on the "ponte de Sen Zacharia" ("fu morto"). He was stabbed in the neck. His reign is indicated with "ani IIII et mensi III".

Pietro Marcello meant in 1502 in his work later translated into Volgare under the title Vite de'prencipi di Vinegia , the doge "Vitale Michiele Doge XXXII." "Fu sostituito doge" ('was substituted as doge'). Here, too, there is no question of a choice as it was otherwise customary. As with Andrea Dandolo, Marcello sent an extremely large fleet to Syria, “la maggiore che mai si facesse” ('the largest that has ever been built'). It is said of it that it comprised 200 ships and that it was commanded by Arrigo Contarini and by "Michiele figliuol del Doge", the son of the Doge, Michele. According to Marcello, the Venetians off Rhodes were 'provoked by Pisans' and it is said that there was a great battle. The Venetians would have “XVIII. navi ”, they would have taken 4,000 prisoners. But they returned the fleet and prisoners, but held “XXX. de 'piu nobili ”, thirty' the noblest '. On the continuation of the journey the Venetians took "Smirre", which had remained without protection. From there the relics of St. Nicholas to San Nicolò di Lido. The fleet continued along “Panfilia” and “Cilicia” ( Pamphylia and Cilicia ), then it reached Syria and finally “Zaffo”. There the Venetians supported the besiegers of Jerusalem with food, conquered Ascalon and “Caifa” after the Venetians had acquired “Tiberiad”. Some claim, according to Marcello, that these undertakings were carried out by the French; others, Venetians and French, together. Then the fleet returned. During this time the relics of St. Isidore was taken to the Church of San Salvatore . Then the Venetians would have allied themselves with "Calamano", the son of the Hungarian king, against the "Normandi", the Normans of southern Italy. After the sack of Brindisi , the fleet returned home with rich booty. During this time, Marcello continues, “Matilde donna illustre della famiglia di Sigifredo”, with Venetian help, managed to conquer Ferrara. As a reward, the Venetians received "esentione perpetua", that is, permanent tax exemption for their trade. The Doge died in the 4th year of his "Prencipato".

According to the chronicle of Gian Giacomo Caroldo , which he completed in 1532, “Vital Michiele” was made known as a doge (“pubblicato”) in the year “MXCVI”, ie 1096. Caroldo claims the Venetians decided to assist the Crusaders in conquering the Holy Land. 'Immediately' (“subito”) they sent “Badoario da Spinal” and “Faliero Storlado” to Dalmatia in order to win over the local residents to participate. 'Driven by the vigor of our Holy Faith and by the loyalty sworn to the Venetians' (“mossi dal zelo della Santa Fede nostra et della promessa fedeltà a Venetiani”) they provided men. The popular assembly convened in San Marco elected “Henrico Contarini Vescovo” and the Doge's son, Giovanni Michiele, as “Capitano Generale dell'armata”, the leader of the fleet, which consisted of 200 ships. This fleet took in the Dalmatians and sailed with favorable winds to Rhodes, where they were forced to winter. Emperor Alexios , who did not trust the crusade and especially the “Francesi”, tried to persuade the Venetians to repent, but they feared the “injustice of God and the hatred of the whole world”. A dispute arose with a Pisan fleet consisting of 50 galleys, which sailed under the imperial flag. Of the Pisan fleet, only 22 galleys escaped. The Venetians, who wanted to show their Christian sentiments, released more than 4,000 prisoners. These were returned, but 30 "principali" were held prisoner. Then the Venetians drove to “Zaffo” to visit the holy grave there. Caroldo then describes the conquests of the Venetians, who drove home after "Goffredo" had granted them an immunity privilege. The Doge "concesse all'Abbate di San Benedetto di Povegio la Chiesa di San Cipriano, nel lito di Malamocho", a church that was directly subordinate to the "Ducal Capella" in order to build a monastery there. However, this monastery "dopò fù dal mare ruinato", it was destroyed by the sea, and the monks went to Murano , where they founded a monastery of the same name. In the last year of the Doge, the "Contessa Matildi" besieged Ferrara with the help of the Venetians and Ravennates and took the city. After the Doge had ruled for five years and four months according to Caroldo - in the Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo it had been four years and three months - he died and was buried “nel portico della Ducal Capella”. The author then describes the course of the First Crusade in unusual detail (pp. 100–122).

Heinrich Kellner , who sees the 33rd Doge in the new "Hertzog", thinks in his Chronica , published in 1574, that this is Warhaffte actual and short description, all people living in Venice , "Vitalis Michiel" was "the next Hertzog / in jar 1096" . Because of the crusade, writes Kellner, which made Venetian historiography known in the German-speaking area, Venice had "a very large armada equipped / nothing like that was seen again". "As they say" it consisted of 200 ships, "whose colonels were / Heinrich Contarin / and Michiel deß Herthaben Son". As with the earlier chroniclers, the Pisans lost 18 ships off Rhodes and 4,000 men were taken prisoner, but the Venetians had returned ships and crews, even though they had "kept thirty of the Fürnemest and Noblest to Geißlen". The fleet conquered Smyrna, whose "garrison servants had escaped from it". "S. Niclas Body "was brought to Venice and" placed in the church a Lito ". Kellner also describes the events in the Holy Land analogous to Marcello, including the doubts whether the Venetians would have done this alone, because: “Partly they wanted to / they did it with each other and shampered hand.” He also describes the whereabouts of the relics of the St. Isidore, the sack of Brindisi , the conquest of Ferrara. "Mechtilde" gave "the Veniceers eternal freedom / from all the burdens in the place of Ferrar / meanwhile through ire hülff they had received the victory." The doge died at Kellner "in the end of the fourth year of his Hertzogthumbs".

In the translation of Alessandro Maria Vianoli's Historia Veneta , which appeared in Nuremberg in 1686 under the title Der Venetianischen Herthaben Leben / Government, und Absterben / Von dem Erste Paulutio Anafesto an / bis on the now-ruling Marcum Antonium Justiniani , the author counts, deviating by Pietro Marcello, "Vitalis Michiel, The 33rd Hertzog". “Among other Christian potentates of strong war armor now / the Venetian ship fleet was not the least / sintemal the same for this conquest in great haste / but in the best order / eighty galleys / 32nd war fifty somewhat lighter / and still a lot other small ships / bit into the two hundred sails strongly pushed into the Adriatic Sea / which Henrico Contarini as general / and Johanne Micheli the son of Hertogen / as captain / to argue against the unbelievers / of the Republic have been entrusted. “In addition to the more precise The author also offers an explanation of the number of ships and the distinction between “General” and “Capitain” for the battle with the Pisans. These had "caused the Venetian ship fleet a lot of trouble every day" and offered it "a meeting". The Pisans lost 28 galleys with him, otherwise he follows earlier authors down to the number of hostages. Here, too, the Venetians conquered Smyrna, but they did not only take the relics of St. "Nicolaus", but also that of St. Theodor with. According to the author, the Venetians released the last 30 Pisans on this occasion: “Because of the extremely high degree of joy”. In Syria they took "the famous Seehaven Joppe, which was hereafter called Jaffo", this time without a doubt, together with the French took Askalon . When it comes to “Tolemaide and Tiberiade”, “some” mean that they were “conquered by the French and not by the Veniceers”. The author describes in detail the enthusiastic reception of the returnees, and that "St. Niclaus Cbody" was brought to Lido, "Theodori was placed in the hearty temple of St. Salvator." Vianoli also knows that this is the case when Puglia was sacked extended over three months. Under Vitale Michiel, according to Vianoli, “the church of SS. Menna and Geminiano”, “stood in the middle of St. Marcus Square / placed on top of it”. The Ziani and Badoer had “built his / her up” on the H. Maurinii. After "five to almost six years of government" the doge died and "by the usually unanimous acclamation of the people" his successor "Ordelafus Falier" was elected in the "eleven hundred and second years".

In 1687 Jacob von Sandrart sufficed in his Opus Kurtze and increased description of the origin / recording / areas / and government of the world-famous republic of Venice : “In 1094. Vitalis Michaël was appointed (XXXII.) Hertzog, who moved with one Fleet of 200 ships in Jonien / in the first Creutz voyage to the war against the unbelievers / but died after four years / but others belong to him for eight years. ”Von Sandrart was obviously very aware of the uncertainty of the chronology.

Historical-critical representations

Johann Friedrich LeBret published his four-volume State History of the Republic of Venice from 1769 to 1777 , in which he stated in the first volume, published in 1769, that “Vital Michieli” had “gained a lot of experience in state affairs in the service of his fatherland and in some embassies”. “He was decreed as a doge whose government was the curious time when this republic was enriched and enlarged through sacred conquests.” “It was resolved to take the sacred places from the Turks, and the popes knew this to be a work of religion to sell what should distinguish the Christian from the unbeliever ... If we find much ill-considered, much contradicting, much inconsistent in the enterprise of these crusaders, then perhaps Venice acted solely on the principles of the purest statecraft ”(p. 282). Venice never left its fleet to the clergy; they avoided quarreling among themselves, "the Venetians had the sea open and received food with less complaint." They also maintained good relations with Emperor Alexios. "All these considerations made the Crusades much more beneficial for them than for all other more distant nations." LeBret also reports that Venice sent "Badoer von Spinale, and the Falier Stornato" to Dalmatia. The "Bishop of Castello, Heinrich Contarini" became "Supervisor in religious matters", the "Son of the Prince, Johann Michieli" "General Captain". Here, too, the fleet picked up reinforcements in Dalmatia and sailed to Rhodes to winter. When Contarini heard of secret negotiations that Alexios had begun with the aim of persuading the fleet to return home, "he threatened them with the wrath of God if they turned their hand from the plow." LeBret rejects the assumption that Alexios was with the Pisans who reached Rhodes with 50 ships, traded in agreement. The imperial flag only served to deceive the other crusaders about their selfish motives. When a dispute about wintering became apparent, the Venetians sent against the Pisans, after they had replied "boldly" that "they would get themselves right by force." The Venetians also took 4,000 prisoners at LeBret, but hardly twelve galleys escaped the prisoners were released when it was heard that some crusaders were among them. However, the Venetians did not keep 30, but “three hundred of the noblest, as a scourge with them” (p. 284). While the imperial general Johannes Dukas was besieging Smyrna from the land, the Venetians attacked them from the sea. "The Venetians themselves, who give us such confused news about these trains," admit that they tortured a clergyman who told them where to find the relics. Later the fleet entered the port of "Joppa, later called Jaffa, or Zaffo". "By all means the Venetians wintered in Jaffa". While Jerusalem was being conquered, Venice only secured the sea and supplies of food. Only after the end of the fighting did the Venetians visit the holy places "where the Christians had wreaked such a terrible bloodbath". In the second attempt it was possible to conquer Ascalon, which this time the Venetians cut off; similar to caipha. “Your company took the form of a commercial speculation”. It was not about conquest or colonization, but about "freedom of action" and precisely those advantages that had been enjoyed in the Byzantine Empire since 1082. After Gottfried's death on July 8, 1100, the fleet went home. - Although the King of Hungary had been "married to a daughter of Count Rogerius of Sicily" since 1097, he entered into an alliance with Venice, because this "Colomann" had taken possession of Croatia and was trying to secure his kingdom . The ships of Venice transported his men to Apulia, who plundered the country there, while Venice held Brindisi and Monopoli . Roger promised not to disturb the Adriatic anymore, whereupon the Venetians and Hungarians withdrew, but with the help of the Pisans he recaptured the two cities (p. 287). - "Mathildis, the famous Countess, one of the smartest ladies of this time, who knew how to rule her states independently, had to experience an outrage in the midst of her happiness ... Ferrara wanted to shake off her yoke" (p. 287). But through negotiations they got Ravenna on their side, Venice's fleet blocked the Po . After Ferrara surrendered, Mathilde gave the Venetians freedom from all duties and taxes in Ferrara, for which the "Doge Michieli" years were "very profitable times". According to LeBret, the Doge died after a reign of five years and five months. He "was buried in the entrance of the ducal chapel", according to the marginal note , this happened in 1102.

In his Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia from 1861, Francesco Zanotto grants the popular assembly greater influence, but this people is always 'gullible because ignorant' ('credulo perchè ignorante') and 'fickle as the sea'. But when Vitale Michiel was elected, it was hoped for better days under an experienced and cautious man. Zanotto believes that Samuele Romanin , whom he calls the “compilatore della Storia documentata di Venezia”, contradicts himself, because the Venetians were guided by both their religious impetus and their economic interests. Zanotto claims that the Venetian fleet consisted of 80 galleys, 55 tarets or "caracche", ships that were suitable for both war and trade. He also believed that half had been stationed in Venice and the other half in Dalmatia. As some said, according to the author, the Bishop of Castello was on board as an advisor, while others said he was the commander (p. 81). In 1097, according to the author, this 'united fleet' went to Rhodes. Then he just gives keywords about the further process. He admits that for some these events went back to a single naval expedition, while others assumed two, but the latter is attested by the facts themselves, but also by the reports of some other "autori stranieri". - After Zanotto, the Normans again troubled the seas off Dalmatia, and so the Venetians allied themselves with the King of Hungary in order to conquer Brindisi and Monopoli instead of attacking Durazzo , which they had occupied . - Margarethe tried to regain Ferrara, which had been lost a few years earlier, and so the siege began in autumn 1101. According to Zanotto, the Venetians not only received a few privileges, but also the right to use a “visdomino, o console” to protect the shops. Sanudo was wrong when he claimed that the doge was buried in St. Mark's Church. According to Zanotto, he was buried in San Zaccaria . Some chroniclers, according to the author, claimed that a certain "Marco Cassolbo o Cassuolo" - Marco Casolo is meant - murdered the Doge, a confusion between the two Doges of the same name that appeared earlier.

Samuele Romanin , the historian embedded in the broader historical context and who portrayed this epoch in the second of ten volumes of his Storia documentata di Venezia in 1854 , expressed himself less in an educational and moralizing way than looking for contemporary motifs . For Vitale Michiel's epoch, he paints a picture of European societies that was characterized by isolation, diversity of developments, little exchange: “Il signore feudale nojavasi nel suo castello, lo schiavo alla gleba gemeva sotto il giogo” ('The feudal lord got bored of his castle, the slave on the ground to which he was bound, groaned under the yoke '). According to Romanin, the investiture controversy broke out in this world, disputes broke out everywhere, and the seaside towns, especially Venice, "ricche, commercianti mettevano a profitto le altrui passioni e la rozzezza", so they benefited from the passions and rawness of others . When the calls for a crusade became loud - Emperor Michael VII had already asked Pope Gregory VII for help against the Seljuks and sought the reunification of the church, which had been divided since 1054 - the meeting in Clermont took place (November 1095). Romanin noted with great regret that it was precisely at this time that the Venetian historians were silent. Romanin describes page by page the course of the crusade, the excesses of which he can only explain in terms of low descent, greed for prey and blood, the participation of criminals and fanaticism (p. 13). Venice could expect an increasing number of pilgrims who would now flock to the Holy Land. “Vitale Michieli” showed the “generale assemblea” not only the meaningfulness, but above all the favor, the benefit, and that the Venetians should not lag behind, especially with regard to the rival cities of Genoa and Pisa (P. 14). Romanin is thus a typical representative of contemporary attempts to explain crusades. For more than a century, the accent was to be on proto-colonial, economic and military thought patterns, which were only developed by more recent research through the development of new sources, but also through the shift to religious, legal and social conditions, but above all to the motives for the participation focused, as well as the reasons for the enormous endurance of the crusade movement. The self-image of the pilgrims , the clergy and the knighthood plays a key role, for example their belief that they can wash off sins through earthly deeds, as it were, on their own. The expected sufferings of a crusade could do this at a time when the forgiveness of a cleric was by no means considered sufficient, as was the case in the Counter-Reformation . The fleet therefore set sail under the command of the son of the Dog. Bishop Enrico Contarini, who, by the way, was the first to replace the name Olivolo with Castello , was to be the spiritual leader of the company; two Proveditors were planned to provide the ships from Dalmatia. The Doge celebrated a mass in San Marco, where “Pietro Badoaro patriarca di Grado” presented the Vexillum with the cross to the Doge, who presented his son with the coat of arms of the Republic (p. 14). The fleet spent the winter on Rhodes, Emperor Alexios wanted to dissuade the Venetians from their plan, the said battles with the Pisans broke out. After the victory over the competitors, the fleet continued in the spring, with Bishop Enrico, who was already in San Nicolò di Lido for the relics of St. Nicholas had prayed, had the fleet sail to Myra , the place of origin of the saint. The city is almost deserted because it was destroyed by the Turks, reported scouts ("esploratori"). In order to obtain the relics, the Venetians engaged in “eccessi”, like torture. However, since the four guards did not reveal the location, the relics of St. Theodore and the uncle of the same name of the in vain saint. But shortly before they set off, a “soave fragranza” showed them the reliquary site under an altar. The Venetians released the captured Pisans out of joy. Romanin cites the storia of a contemporary, Paolo Morosini , as evidence of this process, which deviates from the depiction of Andrea Dandolo , which can be found in “Corner, Notes storiche della chiesa ecc. "As Romanin notes in a footnote (p. 16, note (1)). The Venetian historians would not report anything about the events in the Holy Land, as the author states. Finally, Romanin describes the battles for Ferrara and with the Normans. He considers the attack on Apulia, especially on Brindisi and Monopoli, carried out by the aforementioned “flotta ungaro-veneziana” as an act of 'piracy' and 'reprisals'.

When looking at the motifs of the crusaders, especially the Venetians, the same applies to Heinrich Kretschmayr as to Romanin, even if he argues differently in many respects. In the first volume of his three-volume History of Venice , which appeared in 1905, he counts the time of Doge Vitale Michiel as part of the phase that he describes as the “position of great power”. The motives for the participation of the Venetians were primarily of an economic nature, as he shows in many places. According to Kretschmayr, the Doge ruled from "December 1096 - December 1101 (?)". He "probably gave the suggestion himself to sail a sizeable fleet under the double orders of his son Giovanni and the bishop Enrico von Olivolo, son of the former doge Domenico Contarini". This first touched Grado, "then once again took the cities of Dalmatia into oath and duty, drew the auxiliary ships they had prepared, landed on October 28 on Rhodes, the usual wintering spot on trips to the holy land." Then the Pisans appeared. "That the Venetians would have asked the opponents to stand in line as good Christians from the fight seems likely at most in view of the attested superiority of the enemy fleet." The victors released their "4000 (?)" Prisoners "- tellingly enough - against the promise never wanting to trade in Greece (November 1099). ”The Byzantines had already had to fight the Pisans in August, but they could not be persuaded to return. On May 27th, the Venetian fleet left Rhodes, robbing Myra of his relics, especially St. Nicholas, landed briefly in Cyprus , only to arrive in Jaffa before the summer solstice. This was an opportune time because the Pisans had returned home shortly after Easter . In Jerusalem, the Venetians received a contract that promised them a third of all cities conquered together, "in every other city a church and a marketplace, freedom from taxes and beach rights in all Christian ports". They should keep the unconquered Tripoli in their entirety . "For this they should do relief work until August 15th." At the beginning of October Haifa fell . Kretschmayr assumes that soon after the conquest of Akkon (1104) they mostly exchanged the property there for property there. The Venetians also received privileges in Antioch . Allegedly on St. Nicholas Day they returned to Venice. In the Holy Land, Genoa took the place of Venice. "The alleged participation of the Venetians in the siege of Acre (1104) and Berytus (1110) is a later fiction of local sources, which the ancestors wanted to show more zealously in the service of the Lord", says Kretschmayr. Venice did not intervene again until 1110 before Sidon . According to Kretschmayr, the cause of this long-term retreat was the battle with the Normans on the Hungarian side, the war in Apulia. The Doge, who after Kretschmayr was buried again in the atrium of San Marco, not as Zanotto thought, in San Zaccaria, died shortly after the conquest of Ferrara.

John Julius Norwich is also particularly interested in the First Crusade in his History of Venice . After him, the doge waited to assess its “scale” and “prospects of success” before interfering. It was not until 1097, when 'the first wave of crusaders was already marching through Anatolia', that serious preparations began, and it was not until Jerusalem was conquered (Norwich is wrong here) that a fleet sailed out of the port of Lido. The son of a dog, Giovanni, led the fleet to Norwich, while the Bishop of Castello was responsible for the “religious well-being of the expedition”. In Dalmatia, more crew and equipment were added, then they drove around the Peloponnese to Rhodes. But six months after the departure, apart from the conflict with Pisa, nothing had happened for Christianity. "As always in her history, Venice put her own interests first" states Norwich. With the relics of St. For Nicholas of Myra, the time had come, according to Norwich, to achieve something. In the destroyed church there were still three guards who could only show two coffins with relics, namely that of the uncle of the said Nicholas and that of St. Theodore. Under torture, the Venetians could only find out that traders from Bari had the remains of St. Nikolaus had already carried them years ago. But the bishop did not believe them, but fell on his knees in prayer, whereupon the saint's grave became visible shortly before the departure. The relics of the three saints were loaded in triumph. In June 1100 news of the arrival of the Venetian fleet was heard in Jerusalem. For all the advantages the Crusaders conceded to the Venetians, they only lasted until August 15, which Norwich saw as an indication of how desperately the Crusaders needed the naval aid and how harshly the Venetians were negotiating. Haifa, which was mainly defended by the Jews living there who knew what had happened to their fellow believers in Jerusalem, fell against the overwhelming odds on July 25th. Overall, the Crusade was a considerable economic success for Venice, which was enforced with an unusually large fleet that operated for several years. Only the claim that the relics of St. Nikolaus were lying on the Lido, had to be given up in the end, but: "Several centuries were to pass before the claim was discreetly withdrawn."

In 1988 Donald M. Nicol went so far as to assert the legend of the retrieval of the relics of St. Mark is a mere invention that only served to surpass the legendary retrieval of relics in the Apostle Church in Constantinople, namely the Saints Andrew , Luke and Timothy (p. 65). Something similar could be said for St. Nicholas, whose recovery legend has a number of parallels.

swell

- Ester Pastorello (Ed.): Andrea Dandolo, Chronica per extensum descripta aa. 460-1280 dC , (= Rerum Italicarum Scriptores XII, 1), Nicola Zanichelli, Bologna 1938, pp. 221-224. ( Digital copy , p. 220 f.)

literature

- Roberto Cessi : Michiel, Vitale , in: Enciclopedia Italiana (1934).

- Claudio Rendina: I dogi. Storia e segreti. Newton & Compton, Rome 2003, pp. 101-104. ISBN 88-8289-656-0

- Helmut Dumler: Venice and the Doges. Artemis and Winkler, Düsseldorf 2001. ISBN 3-538-07116-0

Web links

Remarks

- ^ Marie-Luise Favreau-Lilie: Securing peace and limiting conflict: Genoa, Pisa and Venice in Akkon, approx. 1200–1224 , in: Gabriella Airaldi, Benjamin Z. Kedar (ed.): I comuni italiani nel regno crociato di Gerusalemme: Proceedings of the Israeli-Italian Colloquium on the Italian Communes in the Crusading Kingdom of Jerusalem, Jerusalem-Haifa 24. – 28. May 1984 , (= Collana storica di Fonti e Studi 48), Genua 1986, pp. 431-447 ( online , PDF).

- ^ Walter Lenel : A trade agreement between Venice and Imola from 1099 , in: Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 6 (1908) 228-231.

- ^ Roberto Pesce (Ed.): Cronica di Venexia detta di Enrico Dandolo. Origini - 1362 , Centro di Studi Medievali e Rinascimentali "Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna", Venice 2010, p. 54 f.

- ↑ Here the author confuses the second bearer of the name Vitale Michiel , who was murdered by Marco Casolo in 1172 , with the doge to be treated here.

- ↑ Pietro Marcello : Vite de'prencipi di Vinegia in the translation of Lodovico Domenichi, Marcolini, 1558, p 56 ( digitized ).

- ↑ Șerban V. Marin (Ed.): Gian Giacomo Caroldo. Istorii Veneţiene , vol. I: De la originile Cetăţii la moartea dogelui Giacopo Tiepolo (1249) , Arhivele Naţionale ale României, Bucharest 2008, p. 100 f. ( online ).

- ↑ Heinrich Kellner : Chronica that is Warhaffte actual and short description, all life in Venice , Frankfurt 1574, p. 23r – 23v ( digitized, p. 23r ).

- ↑ Alessandro Maria Vianoli : Der Venetianischen Herthaben Leben / Government, and withering / From the first Paulutio Anafesto to / bit on the itzt-ruling Marcum Antonium Justiniani , Nuremberg 1686, S. 187-193 ( digitized ).

- ↑ Jacob von Sandrart : Kurtze and increased description of the origin / recording / areas / and government of the world famous Republick Venice , Nuremberg 1687, p. 33 ( digitized, p. 33 ).

- ↑ Johann Friedrich LeBret : State history of the Republic of Venice, from its origin to our times, in which the text of the abbot L'Augier is the basis, but its errors are corrected, the incidents are presented in a certain and from real sources, and after a Ordered the correct time order, at the same time adding new additions to the spirit of the Venetian laws and secular and ecclesiastical affairs, to the internal state constitution, its systematic changes and the development of the aristocratic government from one century to another , 4 vols., Johann Friedrich Hartknoch , Riga and Leipzig 1769–1777, Vol. 1, Leipzig and Riga 1769, pp. 282–287 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Francesco Zanotto: Il Palazzo ducale di Venezia , Vol. 4, Venice 1861, pp. 81–84 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Samuele Romanin : Storia documentata di Venezia , 10 vols., Pietro Naratovich, Venice 1853–1861 (2nd edition 1912–1921, reprint Venice 1972), vol. 2, Venice 1854, pp. 5–21 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Jonathan Riley Smith: The Crusading Movement and Historians , in: Ders. (Ed.): The Oxford History of the Crusades , Oxford University Press, 1999, pp. 1–14, here: p. 14.

- ^ Heinrich Kretschmayr : History of Venice , 3 vol., Vol. 1, Gotha 1905, pp. 215–221 ( digitized , pages 48 to 186 are missing!).

- ^ John Julius Norwich : A History of Venice , Penguin, London 2003.

- ^ Donald M. Nicol : Byzantium and Venice. A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations , Cambridge University Press, 1988.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Vital Falier |

Doge of Venice 1096–1102 |

Ordelafo Faliero |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Michiel, Vitale I. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Doge of Venice |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 11th century |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1102 |