People's Republic of Zanzibar and Pemba

|

People's Republic of Zanzibar and Pemba January 12 - April 26, 1964 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

|

||||

| Capital | Zanzibar City | |||

| population | about 300,000 | |||

| surface | 3067 km² | |||

|

Form of government |

People's Republic | |||

|

Government system |

Military dictatorship | |||

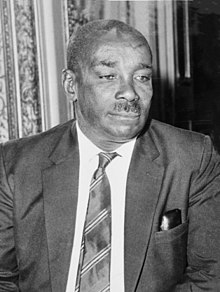

| Head of state | President Abeid Amani Karume |

|||

|

Head of Government January 23rd - April 26th |

Prime Minister Abdullah Kassim Hanga |

|||

| religion | Islam , Christianity | |||

|

||||

The People's Republic of Zanzibar and Pemba was a state on the East African Zanzibar Archipelago in 1964 . It existed less than a year before it merged with Tanganyika to form the state of Tanzania .

history

As a result of the Zanzibar Revolution , in which the sultanate was overthrown, a revolutionary council of the Muslim Afro-Shirazi Party (ASP) and the radical left Umma Party took on the role of an interim government and proclaimed the People's Republic of Zanzibar and Pemba. Sultan Jamschid ibn Abdullah had fled the country in the turmoil of the revolution. ASP boss Abeid Amani Karume took over as president of the council. Abdulrahman Muhammad Babu of the Umma Party became Foreign Minister. Both had been surprised by the coup by revolutionary leader John Okello and were in Tanganyika at the time. First, the new government banished the Sultan and banned the old governing parties Zanzibar Nationalist Party (ZNP) and Zanzibar and Pemba People's Party (ZPPP).

In order to distance himself from the unpredictable Okello, Karume quietly put him on the political side. After all, Okello retained the self-conferred title of field marshal . However, Okello's revolutionaries soon began retaliatory measures against the Arab and Asian populations from the main island of Unguja . The victims were beaten, robbed, raped and murdered. Okello himself stated in radio speeches that he had killed or imprisoned tens of thousands of "enemies and henchmen", but estimates of the actual number of victims vary between a few hundred and 20,000. Some western newspapers wrote from 2,000 to 4,000 dead. The higher numbers could have their origin in Okellos utterances and reports from some Western and Arab media, which were profusely exaggerated. The murder of prisoners of Arab descent and their burial in a mass grave was documented by an Italian film team who shot the scene from a helicopter for the controversial film Africa Addio . It is the only pictorial document of these killings. Many Arabs fled to Oman . Europeans were not attacked on Okellos orders. Before 1964, 230,000 "mainland Africans" and Shirazis , 50,000 Arabs and 20,000 Asians lived on Zanzibar . Post-revolutionary violence did not spread until after Pemba , but the island was closed to foreigners and remained so until the 1980s. The reason was strong opposition to the revolutionary government.

By February 3rd, peace returned to Unguja after Karume was recognized as president by the majority of the population. There were police patrols again, looted shops reopened and weapons were handed in by the civilian population. According to the revolutionary government, the 500 political prisoners should be tried in special courts. Okello formed a paramilitary unit with the Freedom Military Force (FMF) , which patrolled the streets and continued to loot Arab property. The behavior of Okello's men, his violent rhetoric, the Ugandan accent and his Christian faith deterred the majority of the differently oriented residents of Zanzibar and the Muslim ASP. In March Karume's supporters disarmed many members of the FMF and the Umma Party militia . On March 11, Okello was refused entry after a stay on the mainland and the rank of field marshal was revoked. Deported to Kenya , he returned penniless to his old homeland Uganda.

In April, the government founded the People's Liberation Army (PLA), which also disarmed the last FMF militiamen. On April 26th, Karume announced the union with Tanganyika to form the new state of Tanzania. The contemporary press saw the step towards union as a measure to prevent the influence of the communist states. At least one historian sees it as an attempt by the moderate socialist Karume to put the radical left Umma Party in its place. From the politics of the Umma Party, approaches remained in the health, education and social policy of the new government.

Reactions from abroad

British troops learned of the revolution at 4:45 a.m. on January 12 and, at the sultan's request, were put on alert to occupy an airfield in Zanzibar. But Timothy Crosthwait , the British High Commissioner in Zanzibar, did not report any attacks on British citizens, which is why he advised against intervening. Therefore, the alarm time for the troops was extended from 15 minutes to four hours in the evening. Crosthwait also decided against evacuating British citizens, as some of them held important positions in the government. He feared a sudden withdrawal would have negative consequences for the economy and government of Zanzibar. With the new President Karume, the British finally agreed a schedule for an organized evacuation to avoid possible bloodshed.

Within a few hours of the start of the revolution, the American ambassador approved the evacuation of his citizens. On January 13, the destroyer USS Manley docked in the port of Zanzibar City . But the US government had not asked the Revolutionary Council for permission to evacuate, so the Manley crew initially faced armed groups. Approval followed on January 15th. The British saw in this confrontation the reason for the later political unwillingness in Zanzibar towards the western world of states.

Western intelligence services believed that the revolution was supported by communist forces through arms deliveries from the Warsaw Pact . These suspicions were reinforced by the appointment of Abdulrahman Muhammad Babu as foreign minister and Abdullah Kassim Hanga as prime minister. Both were seen as left-wing extremists with ties to the communist world. Great Britain saw in the two close allies of Tanganyika's Foreign Minister Oscar Kambona . In addition, former members of the Tanganyika Rifles (emerged from the colonial King's African Rifles ) are said to have supported the revolutionaries. Some members of the Umma Party wore Cuban combat suits and beards in the style of Fidel Castro , according to which Cuban support was suspected. This fashion came up through ZNP members who had an office of the Zanzibar Nationalist Party in Cuba and spread as a typical style of the opposition party in the months before the revolution.

The People's Republic was the first African government to recognize the German Democratic Republic (GDR) as a state and thus opposed the Hallstein Doctrine . It was also North Korea acknowledged which represented the West a further indication of a communist orientation of Zanzibar. Just six days after the revolution, the New York Times found the country “on the verge of becoming the Cuba of Africa”. On January 26th, however, the newspaper saw no active Communist involvement. In February, however, advisers from the Soviet Union , the GDR and the People's Republic of China arrived in Zanzibar . The influence of the West decreased in the island nation. In July only one dentist was the last British man to be employed by the Zanzibar government. Rumor has it that Israeli agent David Kimche may have been a supporter of the revolution. Kimche was in Zanzibar on January 12, 1964.

The possibility of a communist African state worried the West. In February the British Defense and Overseas Policy Committee stated that even if Britain's economic interests are only "minimal" and the revolution itself "not important", the possibility of intervention must be preserved. The committee feared that Zanzibar could become a center of promotion for communism in Africa, similar to Cuba for America . The United Kingdom, most of the Commonwealth of Nations, and the United States did not recognize the new government until February 23, while most of the Eastern Bloc had long since recognized it. Crosthwait believes that this drove Zanzibar into the arms of the Soviet Union. He and his staff were expelled from the country on February 20 and only left after the United Kingdom recognized the People's Republic.

The displaced sultan sought military assistance from Kenya and Tanganyika in vain, even though Tanganyika sent a hundred paramilitary police to Zanzibar to counter the unrest. Besides the Tanganyika Rifles , the police were the only armed force in Tanganyika. When she was now on Zanzibar, a regiment of the Rifles used it for mutiny on January 20th. The reason was the low pay and the slow exchange of British officers for African personnel. There were similar uprisings in Kenya and Uganda. The British Army and Royal Marines quickly achieved their suppression on the African mainland without major incidents.

supporting documents

literature

- Samuel Daly: Our Mother is Afro-Shirazi, Our Father is the Revolution , Senior Thesis, Columbia University, New York 2009.

- Michael F. Lofchie: What Okello's Revolution a Conspiracy? Transition, 1967, Issue No. 33, pp. 36-42.

- Timothy Parsons: The 1964 Army Mutinies and the Making of Modern East Africa , Greenwood Publishing Group 2003.

- Sergey Plekhanov: A Reformer on the Throne: Sultan Qaboos Bin Said Al Said , Trident Press Ltd. 2004.

- Abdul Sheriff, Ed Ferguson: Zanzibar Under Colonial Rule , 1991, James Currey Publishers, ISBN 0-85255-080-4 .

- Ian Speller: An African Cuba? Britain and the Zanzibar Revolution, 1964 , Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 2007, 35-2, pp. 1-35.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Speller p. 7.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Parsons p. 107.

- ^ Conley, Robert: Regime Banishes Sultan , New York Times, p. 4, Jan. 14, 1964, accessed Nov. 16, 2008.

- ^ A b Conley, Robert: Nationalism Is Viewed as Camouflage for Reds , New York Times, January 19, 1964, p. 1 , accessed November 16, 2008.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times: Slaughter in Zanzibar of Asians, Arabs Told , January 20, 1965, p. 4 , accessed April 16, 2009

- ↑ Plekhanov p. 91.

- ↑ a b c Sheriff p. 241.

- ↑ Daly p. 42.

- ↑ Speller, p. 4.

- ↑ Lonely Planet: History of Pemba , accessed January 30, 2015.

- ^ A b New York Times (Dispatch of The Times London): Zanzibar Quiet, With New Regime Firmly Seated , February 4, 1964, p. 9 , accessed November 16, 2008

- ↑ a b Speller p. 15.

- ↑ a b c Sheriff p. 242.

- ↑ a b c d Speller p. 17.

- ^ Conley, Robert: Zanzibar Regime Expels Okello , New York Times, 11, March 12, 1964 , accessed November 16, 2008

- ^ A b Conley, Robert: Tanganyika gets new rule today , New York Times, p. 11, April 27, 1964 , accessed November 16, 2008.

- ↑ Speller, p. 19

- ↑ a b c Speller p. 8.

- ↑ Speller, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ a b Lofchie p. 37.

- ^ Franck, Thomas M .: Zanzibar Reassessed , New York Times, January 26, 1964, p. E10 , accessed November 16, 2008.

- ↑ Speller, p. 18.

- ↑ Speller pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald : Israeli spymaster found himself embroiled in Iran-Contra , March 16, 2010 , accessed on March 17, 2010.

- ^ Pateman, Roy: Residual Uncertainty: Trying to Avoid Intelligence and Policy Mistakes in the Modern World , p. 161, University Press of Kentucky 2003.

- ↑ a b Speller p. 12.

- ↑ a b Speller p. 13

- ↑ Speller, p. 10.

- ↑ Parsons pp. 109–110