Wild Penfield

Wilder Graves Penfield , OM , CC , CMG , FRS (born January 26, 1891 in Spokane / Washington , † April 5, 1976 in Montreal ), student of Charles Sherrington , was a Canadian neurosurgeon born in the USA .

Life

Family background

Penfield was the son of physician Charles Samuel Penfield and Jean Jefferson. His grandfather was also a doctor. He had an older brother and an older sister. His father owned a practice, but it died, whereupon his mother moved with him and his siblings to their parents in Hudson, Wisconsin . In 1917 he married Helen Katherine Kermott, with whom he had four children: Wilder Graves Jr. (1918–1988), Ruth Mary (later Lewis; 1919–1999), Priscilla (later Chester; 1926–2014) and Amos Jefferson (1927– 2011).

education

He studied at Princeton University , where he excelled in wrestling and American football , graduating in 1913. From 1914 he studied as a Rhodes Scholar in Oxford at Merton College (and in between, after completing his studies, trained the Princeton football team to earn money ). He studied there with Charles Scott Sherrington , who piqued his interest in neurology, and the Canadian Regius Professor of Medicine , William Osler , in whose house he recovered after his ship (he wanted to serve in a Red Cross hospital in France) , the British channel ferry Sussex , fell victim to a German submarine attack in the English Channel in 1916 and sank. He continued his studies at Johns Hopkins University , where he received his MD in 1918. He then began his specialist training with the neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing as an intern at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston. He then returned to Sherrington for a year in Oxford and then spent a year researching neurology in London at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square. He was also on study trips to Spain and Germany (including with Otfrid Foerster ).

activity

In 1921 he returned to the United States, hit a lucrative offer as a surgeon at the Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, to further research in addition to his surgical activities, and went to the Presbyterian Hospital of Columbia University , where he at the surgeon Allen O. Whipple learned and performed his first epilepsy surgeries.

In 1928, at the invitation of Vincent Meredith (a philanthropist and founder of the Bank of Montreal), he went to McGill University in Montreal with the aim of founding his own institute in which neurosurgeons, neurologists and pathologists could work together and research what he did in New York failed because of opposition from New York neurologists. At the same time he was the first neurosurgeon in Montreal at the Royal Victoria Hospital. In 1934 he was able to set up the Montreal Neurological Institute with funds from the Rockefeller Foundation . In 1954 he retired as a professor, but remained director of the institute until 1960. He has also given lectures and lectures worldwide.

plant

In 30 years as a neurosurgeon, Penfield operated on around 750 epilepsy patients, often unsuccessfully at first: "Brain surgeon is a terrible job".

During his operations he often had the open brain of patients in front of him. With weak electrical stimulation with a thin needle, he noticed that the patients did not feel any pain, but had complex sensory impressions such as dreams or hallucinations. Spontaneous movements could also be provoked at certain points. Speech could be disturbed or influenced. Complex, visual sensory impressions were generated. The patients imagined they were seeing or hearing something. They remembered things that had long been forgotten.

In 1937 Herbert Jasper showed him a self-made electroencephalograph . Together with Jasper, he developed a method to locate epilepsy herds more reliably (Montreal method).

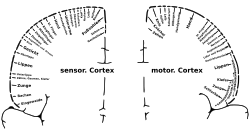

Penfield set itself the goal of systematically examining the different brain regions in order to recognize regularities in the assignment of regions to functions. For years it was initially unsuccessful. The effect of the stimulation changed too abruptly from one tenth of a millimeter to the next. He only found what he was looking for at the central furrow ( sulcus centralis ). On the one hand, muscle contractions can be triggered, on the other hand, sensory perceptions of the same parts of the body can be generated.

His drawing of the body projections in the proportions of their projection fields , the homunculus, became known .

After his retirement he began to write novels, first No other Gods , a new version of the novel Story of Sari by his mother, who died in 1935, which dealt with a biblical topic. His Hippocrates novel The Torch was published in 1960 and his collection of essays The second career in 1963 . In 1967, The Difficult Art of Giving appeared on Alan Gregg , the head of medicine at the Rockefeller Foundation, who had funded his institute at the time, and Man and his family on family education - he was President of the Vanier Institute of Family to the Governor General of Canada Georges Vanier and his wife Pauline Vanier. He also devoted himself to philosophical questions, such as the seat of consciousness or the difference between brain and machine, and wrote a popular science book about it.

Honors

During his lifetime he was referred to as "the greatest living Canadian". In 1952 he received the UK's highest honor, The Order of Merit (the order is only awarded to 24 living people).

In 1960 he received the Lister Medal and the first Royal Bank Centennial Award. In 1966 he was awarded the Otfrid Foerster Medal and in 1975 the Lennox Award of the American Epilepsy Society (AES). He was a Fellow of the Royal Society and several honorary doctorates (including McGill, Princeton, Oxford, Montreal). He was a Knight of the French Legion of Honor, Companion of the Order of Canada (1967) and he received the Medal of Freedom in 1948 . In 1950 he became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences , and in 1953 the National Academy of Sciences .

In 1994 he was posthumously inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame .

According to him, this is Penfield syndrome named, one no longer common name.

The family of elongated instruments in neurosurgery of the same name is also named after him .

Trivia

Before him, only Gustav Theodor Fritsch and Eduard Hitzig and David Ferrier had carried out stimulation experiments on animals. Another scientist, José Manuel Rodriguez Delgado (1915–2011), who carried out similarly spectacular experiments, was forgotten.

Works

- Wilder Penfield, Theodore Rasmussen : The Cerebral Cortex of Man. A Clinical Study of Localization of Function . The Macmillan Comp. New York 1950; Hafner, New York 1968.

- Wilder Penfield, Herbert Jasper : Epilepsy and the Functional Anatomy of the Human Brain . Little, Brown, Boston 1951.

- with Theodore C. Erickson: Epilepsy and Cerebral Localization: A Study of the Mechanism, Treatment and Prevention of Epileptic Seizures. Charles C Thomas, Baltimore 1941.

- with Lamar Roberts: Speech and brain mechanisms. Princeton University Press, 1959.

- The Mystery of the Mind: a critical study of consciousness and the human brain. Princeton University Press, 1975. (popular science book on brain research)

- No man alone. A surgeon's life. Little, Brown and Company, 1977. (autobiography)

- The difficult art of giving. The epic of Alan Gregg. Little, Brown and Company, 1967.

- No other gods. Little, Brown and Company, 1954.

- The Torch. Little, Brown and Company, 1960.

- Second career. With other essays and addresses. Little, Brown and Company, 1963.

- Man and his family. Toronto 1967.

- Editor Cytology and pathology of the nervous system. 3 volumes. PB Hoeber, New York 1932.

- with Kristian Kristiansen: Epileptic seizure patterns; a study of the localizing value of initial phenomena in focal cortical seizures. Thomas, Springfield, Illinois 1951.

literature

- Jefferson Lewis: Something hidden: a biography of Wilder Penfield. Doubleday and Co., 1981.

- Wilder Penfield ( English, French ) In: The Canadian Encyclopedia .

Quotes

In one way or another, the question of the nature of mind is a fundamental problem, perhaps the most difficult and significant of all problems. I've spent my whole life as a scientist researching how the brain controls consciousness. Now, in this final summary of my results, I am surprised to find that the hypothesis of dualism (the mind exists separately from the brain) is the more reasonable explanation. - Wilder Penfield: The Mystery of the Mind: A Critical Study of Consciousness and the Human Brain. Princeton University Press, 1975.

Individual evidence

- ↑ etcweb.princeton.edu: Penfield, Wilder [Graves] ; here online ; last accessed on December 15, 2008

- ^ Surgical Instruments: Penfield # 1 - # 5. October 4, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2019 (American English).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Penfield, Wilder |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Penfield, Wilder Graves |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Canadian neurologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 26, 1891 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Spokane (Washington) |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 5th 1976 |

| Place of death | Montreal |