Yakima war

(Yakima War)

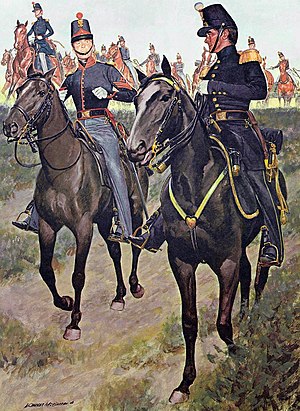

The general scene depicting a battery of light artillery of the US Army from 1855 shows a first sergeant of the light artillery in the left foreground in the uniform of the mounted troops, which has been issued since 1854.

| date | 1855 to 1858 |

|---|---|

| place | Washington Territory |

| output | US troops victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Chief Kamiakin

|

|

- Battle of Toppenish Creek - Battle of Union Gap - Battle of Walla Walla - Cascades Massacre

- Puget Sound War

- Battle of Connell's Prairie - Battle of Seattle (1856) - Battle of Port Gamble

- Coeur d'Alene War

- Battle of Pine Creek - Battle of Four Lakes - Battle of the Spokane Plains

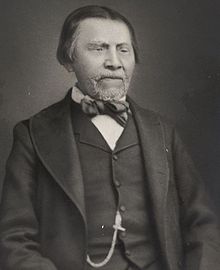

The Yakima War (1855-1858; English "Yakima was") was a military conflict between the United States and the Yakama , a Sahaptian- speaking people of the Northwest Plateau, then part of the Washington Territory , and the tribes allied with them . It took place primarily in the southern center of today's US state Washington . In addition, there were isolated battles in West Washington and the northern Inland Empire , sometimes considered separately as the Puget Sound War and the Coeur d'Alene War (or Palouse War), respectively. This conflict is also known as the Yakima Indian War of 1855 (English "Yakima Native American War of 1855").

On the US side, the 9th Infantry Regiment, the 3rd Regiment of Artillery, the 6th Infantry Regiment, the 4th Infantry Regiment, warriors of the Snoqualmie and militias from Oregon took part. On the Indian side, warriors of the Yakama , Walla Walla , Umatilla , Nisqually and Cayuse fought .

background

The treaties concluded between the United States and various Indian tribes in the Washington Territory resulted in a reluctant recognition by the tribes of the sovereignty of the US government over a vast area. In return for this recognition, they were given half of the fishing rights in the territory, money and food allowances and lands reserved for them on which white settlements would be prohibited.

While Governor Isaac Stevens guaranteed the inviolability of Indian territory after the tribes joined the treaties, he lacked the legal authority to push ahead with the pending ratification in the US Senate . In the meantime, a gold discovery in the Yakama Territory that was made known to the general public led to an unregulated influx of prospectors who traveled uncontrollably across the newly defined Indian territories and were watched with growing disbelief by the Indian leaders. In 1855, two of these proseptors were killed by Qualchin, a nephew of Chief Kamiakin , after she was discovered to have raped an Indian woman.

Outbreak of hostilities

Andrew Bolon dies

On September 20, 1855, agent of the Bureau of Indian Affairs Andrew Bolon departed on horseback to investigate the scene after knowing that the prospectors had died at the hands of Qualchin. However, he was intercepted by Yakama chief Shumaway, who warned him that meeting Qualchin was too dangerous. Heeding Shumaway's warning, Bolon turned and headed home. On this way home he met a group of yakama riding south and joined them. One of the group was Mosheel, Shumaway's son. Mosheel decided to kill Bolon for reasons not fully known. Although a number of the accompanying Yakama protested, their contradictions were overruled by Mosheel, who argued his status. Discussions about Bolon's fate continued throughout the day. Bolon, who did not speak a Yakama, noticed nothing of the conspiracy emerging among his fellow travelers. While resting while Bolon and the Yakama were having lunch, Mosheel and at least three other Yakama rushed at Bolon with knives. The latter yelled "I didn't come to fight you!" In a Chinook dialect before his throat was cut. Bolon's horse was then shot and his body and personal belongings cremated.

Battle of Toppenish Creek

Upon hearing of Bolon's death, Shumaway immediately dispatched an ambassador to the US Army garrison at Fort Dalles before ordering the arrest of his son Mosheel, whom he intended to extradite to local authorities in order to forestall the American retaliation he feared . A council of the Yakama, however, overruled the chief and sided with Shumaway's older brother Kamiakin, who called for war preparation. Meanwhile, District Commander Gabriel Rains received Shumaway's ambassador and, in response to Bolon's death, ordered an expeditionary division to be sent from Fort Dalles under Major Granville O. Haller. Haller's force was received by warriors on the border of the Yakama Territory and pushed back. When Haller withdrew, his group was attacked by the Yakama and put to flight in the "Battle of Toppenish Creek".

Spread of war

The death of Bolon and the defeat of US forces at Toppenish Creek caused panic across the territory and fears that an Indian rebellion was imminent. The same news, however, encouraged the Yakama, and unattached tribes rallied around Kamiakin.

Rains, who had only 350 federal soldiers under his immediate command, urgently asked Acting Governor Charles Mason ( Isaac Stevens was still on his way back from Washington, DC, where he had traveled to present the treaties to the Senate for ratification) for military action Help. He wrote that

“... all available forces in the district must take over the field at the same time. I have the honor of asking you to set up two companies of volunteers to take over the field at the earliest opportunity. The composition of these companies should be as follows: a captain, a first lieutenant and a second lieutenant, two musicians, four sergeants, four corporals and seventy-four soldiers. The greatest efforts should be made to set up and equip these companies at the same time. "

Meanwhile mobilized the governor of Oregon , George Law Curry , a cavalry - regiment of 800 men, a delegation that arrived in Washington Territory in early November. With 700 soldiers under his command, Rains was prepared for a march against Kamiakin, who had set up camp with 300 warriors at Union Gap .

Attack on the White River settlements

As Rains surveyed his troops in Pierce County , Chief Leschi , a Nisqually chief and half-yakama , sought to forge an alliance among the tribes of Puget Sound to bring the war to the front door of the Territorial Government. He started with just 31 warriors under his leadership, but attracted more than 150 Muckleshoot , Puyallup, and Klickitat , despite other tribes rejecting Leschi's offer. In response to news of Leschi's growing army, a volunteer force of 18 dragoons , also known as Eaton's Rangers, was sent out to capture the Nisqually chief.

On October 27, ranger James McAllister and farmer Michael Connell were ambushed and killed by Leschi's men while exploring an area along the White River . The rest of Eaton's Rangers were besieged in an abandoned shack where they were to remain for the next four days before escaping. The next morning, Muckleshoot and Klickitat warriors attacked three settler huts on the White River, killing nine men and women. Many settlers had left the area in anticipation of the raid after being warned of the danger by Chief Kitsap from the neutral Suquamish . Details of the attack on the White River settlements were reported by John King, one of the four survivors, who was seven at the time and - along with two younger siblings - had been released by the attackers and sent west. The King children eventually came to live with an Indian they knew as Tom.

“I told him about the massacre. He said he feared something like that when he heard the fire from that direction. He told me to take the little ones and go to his wigwam and added 'when the moon was in the sky' he would take us to Seattle in his canoe. His squaw was as good and friendly as she could and did everything in her power to make us comfortable, but the little ones were very shy. She got dried fish and blueberries for our meal, but nothing she could do could make the little ones go to her. Our hunger was so great that the different and pungent smells from the food she brought us were no barrier to our enjoyment, as far as I remember. "

Leschi would later express his regret over the attack on the White River settlements, and post-war reports from the Nisqually confirmed that the chief had reprimanded his commanders who organized the raids for the attacks.

The Battle of the White River

Army Captain Maurice Maloney, commander of a company reinforced to 243rd , was previously sent east to cross Naches Pass and reach Yakama Territory from behind. He found the pass blocked by snow and began to return west in the days following the attack on the White River. On November 2, 1855, Leschi's men were discovered by Maloney's vanguard and retreated to the right bank of the White River.

On November 3, Maloney ordered a unit of 100 men under Lt. William Slaughter across the White River to attack Leschi's warriors. Attempts to cross the river at a ford were thwarted by the Indian snipers. An American soldier was killed in the crossfire. Reports of Indian casualties range from one (reported by Puyallup Tyee Dick after the war) to 30 (claimed in Slaughters official report), although the smaller number seems more believable. (A veteran of the battle, Daniel Mounts, was later to be appointed Indian agent for the Nisqually and heard from Tyee Dick's casualty figures, which were confirmed by the Nisqually.) At four o'clock, when it was too dark to cross the river, the Leschis retired Men returned to their camp three miles away on the Green River . They celebrated the successful prevention of the American river crossing. (Tyee Dick would later describe the battle as hi-ue he-he, hi-ue he-he - "great fun".)

The next morning Maloney crossed the White River with 150 men and attempted to attack Leschi in his camp on the Green River, but the poor terrain made the attack impossible, which he immediately called off. Another skirmish on November 5th resulted in five American casualties, but no Indian dead. Unable to make any progress, Maloney began his withdrawal from the area on November 7th and reached Fort Steilacoom two days later.

The Battle of Union Gap

One hundred and fifty miles to the east, Rains met Kamiakin near Union Gap on November 9 . The Yakama had erected a barricade with stone weir for defense, which was quickly removed by the American artillery. Kamiakan had not expected a force of the size that Rains had mustered and foresaw a swift victory of the kind he had won at Toppenish Creek, so the Indian families were there too. Kamiakan now ordered the women and children to flee while he and his warriors wanted to stop the Americans. While he was conducting a scouting of the American lines, Kamiakan and fifty mounted warriors attacked an American patrol that was in pursuit. Kamiakan and his men escaped across the Yakima River ; the Americans were unable to follow them and two soldiers drowned before the matter was called off.

That evening, Kamiakan convened a council to decide to peg the yakama in the hills of Union Gap. Rains began attacking the hills the next morning. Its advance slowed as small groups of Yakama adopted guerrilla tactics to delay the American attack on the main Yakama power. At four o'clock in the afternoon, Maj. Haller, covered by a howitzer bombardment, launched an attack on the position of the Yakama. Kamiakan's warriors dispersed in the bush at the mouth of Ahtanum Creek and the American offensive was ended.

In Kamiakan's camp, plans were made for a night attack on the Americans, but were then dropped. Instead, the Yakama continued their defensive strategy early in the morning the next day, so tired the Americans that they eventually broke off the fight. On the last day of the fight, the Yakama suffered their only loss when a warrior was killed by US Army Indian scout Cutmouth John.

Rains continued on to Saint Joseph's Mission, which was abandoned, the missionaries having joined the Yakama on the fly. While searching the site, Rains' men found a barrel of gunpowder and came to the wrong conclusion that the missionaries had secretly armed the Yakama. A commotion broke out among the soldiers and the mission was burned to the ground. With the onset of snowfall, Rains ordered the retreat and the unit returned to Fort Dalles.

The skirmish at Brannan's Prairie

By the end of November, federal troops had returned to the White River area. A detachment of the 4th Infantry Regiment under Lt. Slaughter, supported by militias under Capt. Gilmore Hays, searched the area previously abandoned by Maloney and attacked Nisqually and Klickitat warriors at Biting's Prairie on November 25, 1855, resulting in several casualties but not a decisive result. The next day, a Native American sniper killed two of Slaughter's men. Finally, on December 3rd, while Slaughter and his men camped at Brannan's Prairie, the unit was shot at and Slaughter was killed. The news of Slaughters death demoralized the settlers in the main cities enormously. Slaughter and his wife were a popular young couple among the settlers and a day of national mourning was ordered.

Conflict in command

At the end of November 1855, General John E. Wool from California reached the region and was entrusted with the control of the US side in the conflict; he took his headquarters in Fort Vancouver . Wool was widely known as puffed up and arrogant, and was heavily criticized by some for blaming much of the Indian-whites' conflicts with whites. After assessing the situation in Washington, he decided that Rains' attempt to track the Yakama bands across the territory would necessarily result in defeat. Wool planned to venture a trench warfare with territorial militias to reinforce the main settlements, while the better trained and equipped US Army would penetrate the traditional hunting and fishing areas of the natives to force the Yakama to surrender through starvation.

To Wool's chagrin, Oregon Governor Curry decided to launch a preventive and largely unprovoked attack against the eastern Walla Walla , Palouse , Umatilla and Cayuse tribes , who had remained cautiously neutral in the conflict up to this point. (Curry believed it was only a matter of time before the eastern tribes entered the war and sought strategic advantage through the first strike.) Oregon militias under Lt. Col. James Kelley invaded the Walla Walla Valley in December , led some skirmishes with the local tribes and eventually captured Peopeomoxmox and several other chiefs. The eastern tribes were now deeply drawn into the conflict, a situation Wool fully blamed Curry for. In a letter to a friend, Wool commented:

“But because of the… barbaric attitude of the Oregonians to exterminate the Indians, I would end the Indian War as soon as possible. It is the shocking barbarism that causes us more trouble than anything else; they are constantly fueling hostilities. "

Meanwhile, Governor Isaac Stevens had returned to the territory on December 20 after a life-threatening journey that included a crossing of the enemy Walla Walla Valley. Dissatisfied with Wool's plan to wait until the spring to resume military operations and learn from the attack on the White River settlements, Stevens rallied the Washington legislature and stated, "The fight shall be punished until The last enemy Indian is exterminated. ”Stevens was also disturbed by the lack of a military escort for him during the dangerous crossing of the Walla Walla and proceeded to denounce Wool for“ the criminal disregard of my safety ”. Oregon Governor Curry stepped up to his counterpart in Washington and called for Wool's dismissal. (The matter came to a head in the fall of 1856 and Wool was seconded by the Army to a command of the Eastern Department.)

1856

Battle of Seattle

In late January 1856, Stevens arrived in Seattle aboard the USCS Active to reassure the city's residents. Stevens confidently stated that "I believe that New York and San Francisco will soon be attacked by Indians as well as Seattle". Anyway, when Stevens spoke, a 6,000-man army of the united tribes was on its way to the unsuspecting settlement. As the governor's ship pulled out of port to bring Stevens back to Olympia, members of the neutral tribes on Puget Sound began pouring into Seattle to seek shelter from a huge Yakama force that had just crossed Lake Washington . The event was confirmed by Princess Angeline , who brought news from her father, Chief Seattle , that an attack was imminent. Doc Maynard began with the evacuation of women and children of the neutral Duwamish by boat to the west side of Puget Sound, while a group of volunteer citizens, led by a unit of Marines of anchored near USS Decatur , the construction of a block building stretch attacked them .

On the evening of January 24, 1856, two scouts from the concentrating Indian units, passing the American guards in disguise, reached the protected Seattle on a fact-finding mission (some believe Leschi himself to be one of the scouts).

Immediately after sunrise on January 25, the American guards spotted a huge group of Indians who reached the settlement under the cover of trees. The USS Decatur began bombarding the woods and drove people into the log cabin for evacuation. The Indian forces - according to some reports made up of Yakama, Walla Walla, Klickitat and Puyallup - returned fire with handguns and began a quick attack on the settlement. Faced with the relentless fire of the Decatur's cannons , however, the attackers were forced to retreat and regroup; a decision was then made to abandon the attack. Two Americans were killed in action and 28 Indians lost their lives.

Actions of Snoqualmie

In order to block the passes over the cascade chain and to prevent further movements of the Yakama towards West Washington , a small jump was built at Snoqualmie Pass in February 1856 . This (called Fort Tilton) went into operation in March 1856 and consisted of a log cabin and several warehouses. The fort was manned by a small contingent of volunteers, reinforced by a 100-man unit of Snoqualmie warriors; these fulfilled an agreement concluded the previous November between the powerful Snoqualmie chief Patkanim and the government.

In the meantime, Leschi had successfully repelled the previous attack by the Americans on the White River against his armed forces and was exposed to a third wave of attacks. As the construction of Fort Tilton progressed, Patkanim - rose to the rank of Captain of the Volunteers - took the lead in a unit of 55 Snoqualmie and Snohomish warriors to capture Leschi. Their mission was triumphantly staged by a headline in the Pioneer and Democrat from Olympia: "Pat Kanim in action!"

Patkanim chased Leschi to his camp on the White River, but a planned night raid was called off after a guard dog barked. Instead, Patkanim, who was within calling range of Leschi's camp, tried to intimidate him with the words “I'll get your head”. Early the next morning, Patkanim began his attack; the bloody fight, according to reports, lasted ten hours and ended only because the Snoqualmie ran out of ammunition. Edmond Meany, a history professor at the University of Washington , would later write that Patkanim returned with "cruel evidence of his slaughter in the form of the heads of killed enemy Indians." Leschis, however, was not among them.

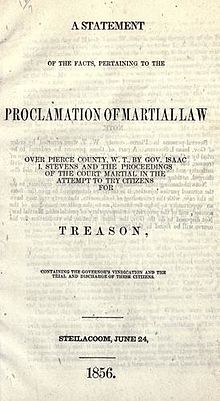

Martial law

By the spring of 1856, Stevens began to suspect the settlers in Pierce County, who had married into the local tribes, of secretly colluding with the Indians by marriage against the territorial government. Stevens' distrust of the Pierce County settlers may have been fueled by strong sentiment from the County's Whig Party and opposition to Democratic policies. Stevens ordered the suspect farmers to be arrested and held at Camp Montgomery. When Judge Edward Lander ordered her release, Stevens declared martial law in Pierce and Thurston Counties . On May 12 put Lander against Stevens order means one. US marshals were sent to Olympia to arrest the governor, but they were evicted from the capital and Stevens ordered the militia arrest of Judge Lander.

Learning from Lander's arrest, Francis A. Chenoweth , chairman of the Territorial Supreme Court, left Whidbey Island , recovering from an illness, and traveled by canoe to Pierce County. Arrived in Steilacoom, Chenoweth called the court together and in turn prepared the release of the settlers through a detention test . Upon learning of Chenoweth's arrival in Pierce County, Stevens dispatched a company of militias to stop the Chief Justice, but the troops were intercepted by the Pierce County Sheriff, whom Chenoweth had ordered to mobilize in defense of the court. The stalemate was eventually resolved after Stevens agreed to give in and release the farmers.

Stevens eventually pardoned himself for the violation, but the United States Senate called for his removal and he was reprimanded by the United States Secretary of State , who wrote to him that “… your behavior in this regard is not that positive reputation of the president is conducive ”.

Cascades Massacre

The Cascades Massacre (Eng. "Cascade Massacre") on March 26, 1856 was named after the attack by a tribal coalition against white soldiers and settlers on the Cascades Rapids . American officers had learned to starve the Indians and damage their economic base by controlling this vital fishing spot. The Indian attackers united warriors of the Yakama, the Klickitat and the Cascade tribes (today identified as members of the Wasco Wishram - Cascade Indians / Watlala or Hood River Wasco ). Fourteen settlers and three US soldiers died in the attack, the greatest loss to US citizens during the Yakima War. The United States sent reinforcements the following day to repel further attacks. The Yakama fled, but nine Cascade Indians fell into the hands of the whites without a fight, including Chenoweth, chief of the Hood River Band; they were immediately captured and executed for high treason.

The Puget Sound War

The US Army arrived in the region in the summer of 1856. In August of that year Robert S. Garnett supervised the construction of Fort Simcoe as a military post. Originally, the conflict was confined to the Yakama, but the Walla Walla and Cayuse were eventually drawn into the war and waged a series of attacks and battles against the US invaders. Perhaps the most famous of these attacks was the Battle of Seattle, in which an unknown number of attackers attacked settlers, Marines and the US Navy before retreating.

Coeur d'Alene War

The last phase of the conflict, sometimes referred to as the Coeur d'Alene War , is considered to be 1858. General Newman S. Clarke commanded the Department of the Pacific and dispatched units under Colonel George Wright to intervene in the current fighting. Wright inflicted a decisive defeat on the natives at the Battle of Four Lakes near Spokane in September 1858. He convened a council of all Indians in the region on Latah Creek (southwest of Spokane). On September 23, he forced a peace treaty on this council that drove most of the tribes into the reservation.

Effects

When the war ended, Chief Kamiakin fled north to British Columbia . Leschi has been charged with murder by the Territorial Government twice (the first attempt resulted in a legal stalemate); on the second charge, which ended with his execution outside Fort Steilacoom, the US Army refused to execute him because of his status as a combatant . (In a 2004 revision process convened by Washington State, the US Army's stance was indulged, and Leschi was posthumously acquitted of murder charges.)

The US Army American Indian scouts tracked down and arrested Andrew Bolon's murderers, who were eventually hanged .

The Snoqualmie warriors were sent out to wrestle the remaining units of the insurgents; the Territorial Government agreed to the premium payment for scalps - this practice was quickly ended by a government appraiser after doubts arose as to whether the Snoqualmie had killed their own slaves instead of the remaining enemies.

The Yakama people were forced into a reservation south of today's city of Yakima .

See also

Individual evidence

- ^ Liz Sonneborn: Chronology of American Indian History . Infobase, 2009, ISBN 9781438109848 , p. 159.

- ↑ David Wilma: Yakama tribesmen slay Indian Subagent Andrew J. Bolon near Toppenish Creek on September 23, 1855 . History Ink. 2007. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ↑ The Murder of AJ Bolon . Washington State History Museum. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014.

- ^ Oregon Historical Quarterly , Volume 19. WH Leeds, State Printer, 1918, p. 341.

- ↑ a b Paula Becker: Yakama Indian War begins on October 5, 1855 . History Ink.

- ↑ THE OFFICIAL HISTORY OF THE WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD VOLUME 2 WASHINGTON TERRITORIAL MILITIA IN THE INDIAN WARS OF 1855-56 . Washington Department of Military Affairs, (Retrieved May 24, 2014).

- ^ A b Robert Utley: Frontiersmen in Blue: The United States Army and the Indian, 1848-1865 . University of Nebraska Press, 1991, ISBN 0803295502 .

- ↑ a b c d e Ezra Meeker: Pioneer Reminiscences of Puget Sound . Lowman and Hanford, 1903.

- ↑ Cecilia Carpenter: Washington Biography: Leschi, Last Chief of the Nisquallies . Eastern Washington University . 1976. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ↑ Becker, Paula: HistoryLink.org Essay 5285, St. Joseph's Mission on Ahtanum Creek . February 23, 2003. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ↑ a b A.J. Splawn: Ka-mi-akin, the Last Hero of the Yakimas . Kilham Stationery & Printing Company, 1917.

- ^ Lieutenant William Alloway Slaughter . Washington Historical Society. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ↑ a b General John Wool . Washington State Historical Society. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ Richard Kluger: The Bitter Waters of Medicine Creek: A Tragic Clash Between White and Native America . Vintage ,, ISBN 0307388964 .

- ^ Reminiscences of Seattle Washington Territory and the US Sloop-of-War Decatur During the Indian War of 1855-56 . US Navy. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ A b Gordon Newell: Totem Tales of Old Seattle . Superior, 1956.

- ^ Mary Ellen Rowe: Bulwark of the Republic: The American Militia in Antebellum West . Greenwood, 2003, ISBN 0313324107 .

- ↑ a b c David Wilma: Governor Isaac Stevens ejects Judge Edward Lander from his court under martial law on May 12, 1856 . Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ↑ Dennis Clay: Concluding Soap Lake by Knapp; continuing Irrigation Project by Weber . In: Columbia Basin Herald , February 15, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ Native Americans attack Americans at the Cascades of the Columbia on March 26, 1856 . HistoryLink .

swell

- Hubert H. Bancroft, History Of Washington, Idaho, and Montana, 1845-1889 San Francisco: The History Company, 1890. Chapter VI: Indian Wars 1855-1856, and V: Indian Wars 1856-1858

- Ray Hoard Glassley: Indian Wars of the Pacific Northwest , Binfords & Mort, Portland, Oregon 1972, ISBN 0-8323-0014-4

Web links

- The Yakima War at HistoryLink.org

- Major Gabriel Rains and 700 soldiers and volunteers skirmish with Yakama warriors under Kamiakin at Union Gap on November 9, 1855 at HistoryLink.org

- Yakama tribesmen slay Indian Subagent Andrew J. Bolon near Toppenish Creek on September 23, 1855 at HistoryLink.org

- Guide to the Yakima War (1856–1858) on the Washington State University Librarywebsite