Nez Percé War

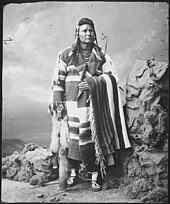

The war against the Nez Percé ( Nez Perce War , occasionally Nimipu War ) in 1877 was a campaign by the United States Army against a group of Indians of the Nez Percé tribe . The Indians, led by Chief Joseph (Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-keht) and other chiefs , refused to move to their assigned reservation and instead fled the Lapwai reservation area of Idaho to Montana and in Towards Canada . From June 17 to October 5, they covered around 2,000 kilometers and were able to inflict several defeats on the pursuing units of the American army under General Oliver Otis Howard , but were finally stopped a few kilometers from the Canadian border and forced to surrender.

background

The tribal area of the Nez Percé was around the Clearwater and Snake rivers in what is now Oregon , Idaho and Washington . They first came into contact with whites in the course of the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1805. In the mid-1830s, Christian missionaries began their work in the tribal area of the Nez Percé. The Presbyterian Henry H. Spalding , in particular , was very committed and also translated chants and prayers into the language of the Indians. However, not all Nez Percé became Christians; the increasing immigration of white settlers via the Oregon Trail also created resistance, particularly from neighboring tribes. In 1847 the Cayuse and Umatilla committed the Whitman massacre and mission stations were closed as a result. It was only more than 20 years later that missionary work began to increase again. Although the Nez Percé remained peaceful towards the whites, the Dreamer cult, which was skeptical of them, arose among the tribal members who did not convert to Christianity . Several influential chiefs of the Nez Percé such as Lawyer and Tu-eka-kas, known as Old Joseph , father of Chief Joseph, remained faithful to Christianity and open to whites. In 1855 a treaty was signed between the Nez Percé and other tribes in the area, on the one hand, and the United States, on the other hand, which gave the Nez Percé the right to a nearly 13,000 square kilometer reservation in their traditional tribal area in Oregon and Idaho. Those who signed included Old Joseph and Allalimya Takanin known as Looking Glass . In exchange for money and goods, the Nez Percé gave up their claim to further east, towards the Bitterroot Mountains , and areas further south. After the conclusion of the treaty, wars broke out between the United States and other tribes such as the Yakima , but the Nez Percé did not interfere and in some cases even supported the United States with volunteers.

Major disputes did not arise until 1863, when the United States presented the Indians with a treaty that would have reduced the reservation they had guaranteed a few years earlier to around 10 percent of the original area. This reduction is likely to have occurred because gold was found in their area. In May and June 1863 there were lengthy negotiations in Lapwai between the Nez Percé, of whom 3,000 were present at times, and Calvin Hale, the chief official for Indian affairs in the Washington Territory . Hale was supported in the negotiations by the two Indian agents Samuel D. Howe and Charles Hutchins, by several units of the army under Colonel Justus Steinberger and by Henry Spalding and Perrin Whitman as translators. The contract led to the split of the Nez Percé: a majority of the chiefs were not directly affected by the loss of territory and agreed to the sale for $ 265,000, another part refused to sign. Old Joseph was one of the chiefs who did not sign the treaty. Chief Lawyer was the leader of the group of the undersigned, and in the treaty designated rather arbitrarily as Head Chief Nez Perces Nation . The United States saw the treaty on the basis of the signatures of the group of chiefs around Lawyer as binding for the entire tribe.

The group of those who did not sign the treaty lived in the southern (lower) part of the tribal area and were therefore called Lower Nez Percé. The Lower Nez Percé refused to leave their home, the Wallowa Valley in Oregon, in the years that followed.

In 1877 the United States commissioned General Oliver Otis Howard to force the Indians into their assigned Lapwai reservation if necessary. Howard, a veteran of the Civil War , who had come to a peace treaty with the Apaches under Cochise in 1872 , was at that time in command of the military area (Department) "Columbia", which included the states of Washington, Oregon, Alaska and parts of Idaho. He was strongly driven by Christian motives, which his superiors in no way shared. They even urged him to keep the soldiery from the "philanthropic" separate. The Indians, for their part, often rejected Christian ideas, even when they were formally baptized. They were still firmly anchored in their own religion. Nevertheless, some of the chiefs developed a certain relationship of trust in the reliability of his word.

The Indians, still undecided as to how to react, made camp on the edge of the reservation. Its leaders, including Chiefs Joseph, White Bird and Toohoolhoolzote , discussed whether to submit and go to the reservation or whether to fight for their freedom.

Meanwhile, a group of young Indians, whose leader had lost his father in quarrels with settlers, led a personal vengeance campaign in the course of which several white settlers were killed. The first blood had flowed and most of the chiefs of the Nez Percé were now convinced that after this act a war with the whites could no longer be avoided. Because of this, they gave up their camp and retreated south to White Bird Creek.

The area of the Nez Percé was from the point of view of the American Army in the jurisdiction of the Columbia Military Area (Department of the Columbia) under the command of General Howard. Howard's immediate superior was General Irvin McDowell, who was in command of the Military Division of the Pacific . Other command posts involved on the American side were the Dakota Military Division (General Terry ), which was subordinate to the Military Division of the Missouri (General Sheridan ). Commander-in-chief of the Army had been General William T. Sherman since 1869 , under whom Howard had already served in the Civil War. The strength of the troops varied. At the beginning of the campaign, Howard was able to lead around 350 men into the battle of Clearwater. As a result of reinforcements, his direct command grew to around 730 men, and more troops were deployed to secure the settlers. Another contingent of troops under Colonel Miles numbered around 520 men.

The Nez Percé had never had a clear leader because they consisted of several small groups, each with their own chiefs and who retained a certain degree of independence even when they fled. Important decisions on the said escape were therefore often made in the council. The fleeting Nez Percé consisted of Joseph's Wallowa group, the White Bird group, Toohoolhoolzote's group from the Salmon area, and a small Palouse group led by Hahtalekin. Later on, the Looking Glass group, based in the Clearwater Tributaries, joined them. As the most famous leader of the Nez Percé, Joseph was one of the group chiefs, but his influence was greater in peacetime than in war. Looking Glass in particular assumed a military leadership position in the course of the campaign. Apart from the chiefs, Joseph's brother Ollokot and the warriors Rainbow (actually Wahchumyus) and Five Wounds (Pahkatos Owyeen) were important military leaders. The strength of the warriors was estimated at 250, which was about a quarter of the total number of the fleeing group. In contrast to the American associations, which could fall back on a deeply graduated logistics, the Nez Percé had to find other ways to supply themselves. Since they still had gold and money due to their pre-war trade, they were able to purchase food from the settlers and traders in Montana. Towards the end of the campaign, they also raided a camp of the Crow Indians, who were friends with them but are now on the side of the Americans , where they stole dried buffalo meat, went buffalo hunting themselves and stole supplies for the US Army at Cow Island Landing on the Missouri . Before they had set up camp on the edge of the reservation, the Nez Percé had collected a large part of their animals, so that they carried numerous horses with them on their march. The population was so large that, according to Joseph, the Nez Percé still owned 1,100 horses and 100 saddles at the end of the campaign. The armament was a mixture of modern and older weapons: in the battle in White Bird Canyon around half of the Nez Percé were equipped with repeating rifles, the rest with a mixture of bows, muzzle-loading pistols and muskets. In this battle, the Indians captured 63 carbines of the US cavalry and an unknown number of revolvers.

course

From White Bird Canyon to Clearwater

In the meantime, General Howard had gathered troops. He sent two companies of cavalry under the young Captain Perry ahead to protect the settlers near the Indian camp on White Bird Creek and to watch the Indians. However, Perry decided to take immediate action against the Nez Percé. On June 17th, Perry's cavalrymen, around 100 men and some volunteers, reached the Indian camp. The chiefs around Joseph sent a group of warriors with a white flag to meet the cavalrymen, but they were shot at. The around 70 warriors of the Nez Percé then returned fire. The American bugler was one of the first to fall, which made it very difficult for Perry to coordinate his troops. Finally, under the aimed fire of the Indians, Perry's flanks gave way one by one and the Americans had to withdraw. The Indians persisted and pursued Perry and the remains of his command for around 30 kilometers. The first battle of the campaign was a clear victory for the Nez Percé; they themselves had only two wounded, while Perry had lost 34 men, around a third of his command.

After this severe defeat, Howard had to be more cautious on the one hand, but also to act quickly at the urging of the local population on the other. He finally started the persecution on June 22nd, but it remained fruitless for two and a half weeks.

A group of Nez Percé led by Looking Glass presented Howard with further problems. While Looking Glass had not been involved in the fighting at White Bird Canyon, he was one of the unsigned chiefs and posed a potential threat. When Howard heard that Looking Glass' people had raided two farms, his Indian scouts reported to him "Several warriors in the group had already joined the fugitives," Howard decided to act. He dispatched Captain Whipple with two companies of cavalry to arrest Looking Glass and his group. Whipple's men, joined by 20 volunteers, arrived at Looking Glass' camp on Clearwater, near what is now Kooskia, on the morning of July 1st. Negotiations were hesitant, but came to an abrupt end when a gun was fired by a volunteer. A shooting broke out and the Indians abandoned much of their property and fled. The establishment of the group failed as a result and Looking Glass' group subsequently joined the other fugitives. So, from Howard's point of view, the operation had achieved exactly the opposite of what was planned. The losses of the Nez Percé are not exactly known, but they were probably three dead and as many wounded; a mother had drowned with her child trying to escape through the Clearwater.

With the fugitives, led by Joseph and White Bird, there were further skirmishes between July 3rd and 5th near Cottonwood , in the course of which an eleven-strong cavalry advance detachment was surrounded and killed.

The chiefs of the Nez Percé around Joseph had in the meantime made the decision to flee north. On the Clearwater River, the fugitives had united with Looking Glass' group, so that a total of around 700 Indians were now on the run. The next battle came on July 11th when Howard attacked the Indian camp on Clearwater. The attack failed, however, and the Nez Percé counterattacked, attacking the Americans on the flank and driving them back. Only the use of howitzers brought the Indians to a standstill and forced them to retreat. In spite of this, the Indians continued to resist, thereby enabling their wives and children to evacuate most of the camp and move on. This second encounter, which cost the Indians 10 and the Americans 40 men, was viewed by the Americans as a victory for their army. Rumors that Howard would soon be replaced and replaced disappeared for the time being and the aide of Howard's superior McDowell telegraphed to him that Howard's élan was unbeatable. In fact, the Battle of Clearwater was more of a tie with advantages and disadvantages for both sides: the Indians had lost some of their belongings, but were still free. Their chiefs now decided to flee eastwards towards the Great Plains . There they hoped for support from their friends, the Absarokee tribe (often referred to as Crow in English).

Big hole

The Nez Percé made its way over the arduous Bitterroot Mountains , via the so-called Lolo Trail . A few miles from Stevensville , Montana, their route was blocked by tree trunks and American troops. Howard had telegraphed Captain Rawn at Fort Missoula , and Rawn had hurried with 35 soldiers and 200 volunteers to the Lolo Trail, where he was going to stop the Indians until Howard's arrival.

When speaking with the chiefs, Rawn suggested they lay down their arms and give up. The Indians refused this request and in return promised to leave the settlers in the Bitterroot Valley in peace if they were let through. Rawn refused to do this. However, his volunteers were concerned about their settlements in the valley and for the most part abandoned the officer. Meanwhile, the Nez Percé had found an unguarded mountain path that the Americans had considered impassable. On him they bypassed the roadblock the next day, leaving Rawn and his position called "Fort Fizzle" (roughly "Fort Failure").

In the Bitterroot Valley, apart from a few incidents, the Nez Percé behaved peacefully towards the settlers and bought the necessary supplies. After leaving the valley behind, the Nez Percé camped on the Big Hole River in Montana. Convinced that they had left Howard far behind, the chiefs wanted to give their tribesmen a few days' rest. After the war Joseph wrote that the Indians believed that they had escaped the war by crossing the Bitterroot Mountains, that peace would now return and that the question of returning home would be settled later. The calm, however, was deceptive. The Nez Percé had left Howard behind for the time being and with the crossing of the Bitterroot Mountains also left Howard's area of command, because Montana was already part of the Dakota Defense Area, which was under General Alfred Howe Terry . However, Howard's superiors, McDowell and Sherman, had instructed him to continue the pursuit regardless of such organizational limitations. Howard had also telegraphed Colonel John Gibbon in Fort Shaw further north, who then rushed to the Nez Percé camp with around 200 soldiers.

At dawn on August 9th, Gibbon ordered the attack and managed to surprise the refugees. Within a few minutes the soldiers conquered a large part of the camp, with not only several warriors of the Nez Percé, but also numerous women, children and old men losing their lives. But Joseph and the other chiefs were finally able to gather some warriors and bring the American advance to a halt with them. Gibbon's troops suffered heavy losses and withdrew to a wooded area near the camp, from where Gibbon Howard asked for reinforcements. Only when these arrived in the course of the next day did the Indians slowly withdraw. The attack cost the Americans 29 men; In addition, 40 men were wounded, including Gibbon. Two of the wounded later died from their injuries. The Nez Percé suffered 60 dead and 90 wounded, including numerous women and children.

In the days that followed, Howard continued in pursuit, staying close behind the Nez Percé, who crossed the border between Idaho, Montana and Wyoming, attacking a truck at Birch Creek on August 15, killing five men. On August 18, a group of warriors led by Joseph's brother Ollokot surprised the soldiers by attacking their camp on Camas Creek , Idaho, driving their mules away. Howard continued the pursuit vigorously and was determined to catch the Indians before they reached the Yellowstone area . Despite great efforts, the Indians escaped again and Howard had to break the chase to give his troops and their horses a rest for four days.

But the Indians also suffered a severe setback, because the Absarokee refused to fight the Americans with them. Without this support, the Nez Percé saw only one way out, to escape to Canada.

The train to Canada

Meanwhile Howard had again ordered another officer, Colonel Samuel Davis Sturgis of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, into the path of the tribe. Sturgis received support from 150 Crow Indians who were hoping to capture horses from the Nez Percé. The fact that the Crow sided with the Americans was another disappointment for the Nez Percé.

Sturgis was supposed to stop the refugees, who had meanwhile reached the area of today's Yellowstone National Park, in the Absaroka mountain range . Like his predecessors, he was misled and circumvented by the Nez Percé. Sturgis took up the chase and reached the Indians on a dry river bed, Canyon Creek in eastern Montana. However, the warriors of the Nez Percé took his troops under targeted fire, stopped them and allowed their relatives to withdraw.

The now exhausted Indians moved north, still pursued by Howards and Sturgis' troops. Individual groups left the main group. One of them ended up in the reservation of the Assiniboine and Gros Ventres at Fort Belknap in Montana. Both tribes were traditional enemies of the Nez Percé and some of the fugitives were murdered on the reservation; It is unclear whether the perpetrators belonged to the Assiniboine or the Gros Ventres. Another small group fell victim to an attack by Assiniboine and Gros-Ventre warriors on October 3: five men were killed and two women captured. There were further arrests by the Crow and Gros Ventres.

The main group of fugitives, meanwhile, encountered a new enemy for the last time, as Howard had telegraphed Colonel Nelson A. Miles , who was marching from Fort Keogh further east. Howard had also noticed that the Nez Percé adjusted to his marching pace and rested when he rested. So, to give Miles the opportunity to intercept the Nez Percé, he slowed down his pursuit. At the end of September, the Nez Percé camped around 40 miles (64 kilometers) from the Canadian border in the Bearpaw Mountains. Here they met the troops advancing from the east. Miles attacked the Indians on September 30th, but was repulsed by the warriors who holed up behind parapets. The losses on both sides were extremely high (the Nez Percé also lost Toohoolhoolzote and Joseph's brother Ollokot, among others), and Joseph and Miles began negotiations.

Meanwhile, the cold set in, and in early October, Howard and his force appeared. Looking Glass was killed in further skirmishes, leaving the Nez Percé with Joseph and White Bird only two chiefs. White Bird refused to give up and escaped to Canada with a group of around 50 Indians on the night of October 5th. Other, smaller groups also made their way north through the American lines. Joseph, on the other hand, was tired of fighting. On October 5th he gave up the fight. Through a translator he let the Americans know:

Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before - I have it in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. [...] It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people - some of them - have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are - perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and to see how many of them I can find; maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.

“Tell General Howard that I know his heart. I have in my heart what he said to me earlier. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. […] It's cold and we don't have any blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people - some of them - have fled to the mountains with no blankets, no food. Nobody knows where they are - maybe freezing to death. I want to have the time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find; maybe I'll find her among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs; my heart is sick and sad. As of the current position of the sun, I will never fight again. "

These words of Joseph have since been among the most famous Indian speeches and are considered "classics of Indian prose". He then offered his rifle to Howard, who, however, indicated that he should hand it over to Colonel Miles, who was standing next to him.

The escape of the Nez Percé, which had led them over 2,000 kilometers and through parts of four American states, came to an end. On their march, the Indians had fought a total of more than 2,000 American soldiers. 65 warriors and 55 women and children had lost their lives in the process, the American losses amounted to 180 dead and 150 wounded.

consequences

Quarrel between Howard and Miles

On the American side, General Howard and Colonel Miles quarreled after the battle. Howard was disappointed with Miles' first report to the newspapers, in which Howard's presence at the surrender and his troops were barely mentioned. Miles, for his part, felt that Howard's official reports to his superiors did not sufficiently appreciate the role of Miles and his troops. The argument lasted for several months and destroyed a long friendship between the two men.

Fate of Joseph's Nez Percé

The Nez Percé were taken to various reservations in Kansas after their surrender . In 1879 they were taken to Indian territory , where many of them died. That same year, the April issue of North American Review published an account of the campaign, told by Joseph and translated into English by Bishop William H. Hare. Joseph made it clear that he still believed that the Lower Nez Percé had never sold their land:

Suppose a white man should come to me and say "Joseph, I like your horses, and I want to buy them". I say to him, "No, my horses suit me well, I will not sell them." Then he goes to my neighbor, and says to him: "Joseph has some good horses. I want to buy them, but he refuses to sell. "My neighbor answers," Pay me the money, and I will sell you Joseph's horses. "The white man returns to me, and says," Joseph, I have bought your horses. " , and you must let me have them. "If we sold our lands to the Government, this is the way they were bought

"Let's say a white man comes up to me and says," Joseph, I like your horses and I want to buy them. "I say to him," No, I like my horses, I won't sell them. "Then he leaves to my neighbor and says to him: “Joseph has some good horses. I want to buy them, but he refuses to sell. ”My neighbor replies,“ Pay me and I will sell you Joseph's horses. ”The white man comes back to me and says,“ Joseph, I bought your horses, and you must give it to me. ”If we've ever sold our land to the government, this is how it was bought. "

Joseph also expressed his love for his homeland, in which his father Old Joseph's grave lay: “I love that country more than the rest of the world. A man who does not love his father's grave is worse than a wild animal ”. He also wrote that Colonel Miles had assured him during the deliberations before the surrender that the Nez Percé would be allowed to go to the Lapwai Reservation after the surrender. Without this promise, Joseph said, he would never have surrendered. Miles also believed that one of the conditions for the Indians surrender was that they were allowed to return to the Lapwai Reservation, and he advocated it, but Howard and General Sherman refused to allow the Indians to return to the Columbia Defense Area. When this did not work, he apologized to Joseph. According to Joseph's memory, Miles asked for understanding that he must obey his orders; if he did not, he would simply be removed and the orders would be carried out by another officer. Howard penned a reply to Joseph's report that appeared in the July 1879 edition of the North American Review. Howard showed himself open to the original concerns of the Indians:

If I had the power and the management entirely in my hands, I believe I could have healed that old sore, and established peace and amity with Joseph's Indians. It could only have been done, first, by a retrocession of Wallowa (already belonging to Oregon) to the United States, and then setting that country apart for ever for the Indians [...]; and, second, by the removal therefrom of every white settler, making to each a proper renumeration for his land and improvements. But this power I did not have

“I believe that if I had had the authority and leadership fully in my hands, I could have healed this old pain and made peace and friendship with Joseph's Indians. First, this could only have happened by transferring the Wallowa (which already belonged to Oregon) back to the United States in order to then reserve this land forever for the Indians [...]; and second, by removing every white settler from the area, paying compensation for his land and the improvements he made. But I didn't have that power "

But he resisted some representations by Joseph and the press, which blamed him for the outbreak of war. Howard also described how, as a military commander, he became involved in the problems with the Nez Percé: On the one hand, he received complaints from white settlers, some in official form. On the other hand, the Indian authorities also requested military support, whereupon Howard received corresponding orders from higher-level command posts. His job, according to Howard, was to prevent fighting between armed settlers and Indians, to get the roaming Indians into the reservation made for them and to restore peace. Regarding the terms of surrender, Howard argued that the escape of the Indian group, led by White Bird, represented the first violation of the regulations by the Indians. In addition, Howard pleaded for the Nez Percé to be left in Indian territory for the time being. It was not until 1883 that some of them were allowed to return to the rest of the tribe on the Lapwai reservation in Idaho. Joseph and others were not granted this, however - they were moved to the Colville Reservation in Washington state . Joseph spent the rest of his life fighting to return to his beloved homeland - in vain, as he died in Colville in 1904.

The fate of the Nez Percé who escaped to Canada

Before and after Joseph's surrender, several groups of the Nez Percé had made their way through the American lines and to Canada, where they set up camp with the Sioux Sitting Bulls under the leadership of Chief White Bird . Flight, displacement and exile in Canada bound the previously warring Sioux and Nez Percé together, and the Sioux provided the newcomers with food in the early days. In the spring of 1878, some of those who fled to Canada attempted to return to the United States and join their relatives in the Lapwai Reservation. However, they were not allowed to do so; the men were first arrested at Fort Lapwai, later the newcomers were sent to Joseph in Indian territory. An official attempt by the American government to persuade White Bird and the rest of his 120-strong refugee group to return failed. In the course of the following years, however, there was a steady emigration of Nez Percé, who longed for their homeland. A few families, including White Bird, remained in Canada even after Sitting Bull returned to the United States. White Bird was murdered by another tribe member in 1892 after a dispute. The last Nez Percé woman left in Canada died of tuberculosis in 1899 .

reception

The American public had already followed the escape of the Nez Percé closely during the campaign. After the surrender of the Nez Percé, Joseph in particular moved to the fore, who fought hard to get his tribe members back to the Lapwai reservation. In 1879, the same year his article appeared in the North American Review , he traveled to Washington to address ministers and congressmen, and in 1897 rode alongside Miles and Howard in the New York inauguration parade for President Grant Tomb.

The public interest also manifested itself in the numerous books about the campaign, some of which were published shortly after its end. In the December issue of the monthly magazine The Galaxy , a report by FLM on the campaign appeared as early as 1877 . Howard's book Nez Perce Joseph: An Account of His Ancestors, His Lands, His Confederates, His Enemies, His Murders, His Wars, His Pursuits and Capture was published in 1881, followed in 1884 by his adjutant CES Wood with an article in Century Magazine , and in 1889 GO Shields' book The Battle of the Big Hole . There were also publications in the following years, for example Yellow Wolf — His own Story , published in 1940 , in which Lucullus Virgil McWhorter wrote the life story of the Nez Percé warrior Yellow Wulf, who died in 1935.

Helen Hunt Jackson dedicated a chapter of her book A Century of Dishonor , published in 1881, to the Nez Percé and criticized in particular that the Nez Percé were not allowed to return to the Lapwai reservation contrary to the original surrender conditions: "The conditions of this surrender were shamefully violated". In addition to Helen Hunt Jackson, the Presbyterian Church and the Indian Rights Association also campaigned for the Nez Percé. Public pressure is also seen as a factor that eventually led the American government to move Joseph to the Colville Reservation and part of his group to Lapwai.

In addition to the conditions of surrender, the treaty of 1863 was also viewed critically (for Joseph's view, see the quote in the section above). The United States had guaranteed the Nez Percé in 1855, among other things, the Wallowa Valley and acquired it in 1863 from a group of chiefs who did not live in it or even "owned" it. Howard's adjutant Charles Erskine Scott Wood wrote about this as early as 1884:

But no matter how consistent their action may have seemed to them, to the Indians it was false and absurd. With them, as with all warlike, nomadic peoples, the decision of a majority is not regarded as binding the minority; this principle is unknown.

“But no matter how logical their action may have seemed to them [the Indian agents, the author], to the Indians it was wrong and absurd. With them, as with all bellicose nomadic peoples, the decision of a majority is not regarded as binding on the minority; this principle is unknown. "

Similar criticism is found in a December 1877 report in The Galaxy magazine. The magazine cites an 1873 commission that concluded that “if the laws and customs of the Indians are to be respected in any way so the treaty of 1863 does not bind Joseph and his group ”. At the same time, however, the commission also warned that, for security reasons, either the Indians or the white settlers would have to be removed from the disputed area. Alvin M. Josephy junior comes to a similar conclusion in his 1965 The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest : He sees the contract of 1863 as a "deceitful act" and continues to write, (Old) Joseph and the other unsigned groups outside of the new reservation, "in the truest sense of the word, the land under them had been sold".

It is noteworthy that the struggle and, above all, the behavior of the Nez Percé was viewed and described positively by many Americans, including their direct opponents. William Tecumseh Sherman wrote that the campaign against the Nez Percé was "one of the most extraordinary Indian wars". The Indians, Sherman said, “showed a courage and skill that earned universal praise. They refrained from taking scalps; released captive women; did not commit indiscriminate murders of peaceful families, as is usual, and fought with almost scientific skill, making use of fore and aft guards, skirmish lines and field fortifications. " Howard's adjutant, Charles Wood, wrote in Century Magazine in 1884 : "Joseph [...] fought for what the white man, if successful, calls" patriotism. "

This positive view was also evident in the military analysis of the campaign and in particular in the way in which Joseph was received by the American public. As the last remaining chief of the Nez Percé, Joseph had given up his escape and handed over his rifle to Howard and Miles and remained a kind of spokesman for the fugitives. For this reason, the attention of the Americans was mainly focused on him and he was seen as the sole political and, above all, military leader of the Nez Percé. This is particularly evident in Howard's book title: "Nez Perce Joseph: an account of his ancestors, his lands, his confederates, his enemies, his murders, his war, his pursuit and capture". Howard certified Joseph “remarkable leadership” and praised his military skills. This image of Joseph was strengthened in the following years, he was transfigured as the "Red Napoleon", and in the middle of the 20th century there were even admirers who demanded that he be posthumously appointed five-star general of the American army.

At the same time, however, the role of Joseph began to be questioned. Analysis of Indian statements and reports, particularly by Lucullus McWhorter, showed that Joseph was primarily a leader in peacetime. A study based on this by Bruce Haines from 1954 confirmed this picture. Haines did not see the success of the Nez Percé as being based on the genius of a single leader. On the one hand, with Looking Glass, White Bird, Toohoolhoolzote, Ollokot, Rainbow and Five Wounds, a number of warriors were involved in leading the battles; on the other hand, the individual warriors also played a decisive role in the successes. Haines therefore concluded that Joseph was not the main military leader of the Nez Percé, a finding shared by later authors.

Haines sees a further reason for the transfiguration of Joseph as a military genius in the unsuccessfulness of the Americans involved: "In order to downplay their own mistakes and weaknesses, the officers tended to exaggerate the skill of the Indian leaders." Other authors attest to Howard and his subordinates Better picture: He also suffered from supply problems, especially when it came to fresh horses, and he was simply unlucky in several places (e.g. at Fort Fizzle). It is therefore doubtful whether the long duration of the campaign Howard's mistakes or rather these external circumstances were due.

Memorials

The battlefields of the campaign are now part of the Nez Perce National Historical Park , along with other Nez Percé historical sites (such as Joseph's grave) , which includes a total of 38 sites in the states of Idaho, Montana, Oregon and Washington. The route of the Nez Percé has been part of the National Trails System since 1986 under the name Nez Perce National Historic Trail .

Literary and cinematic adaptations

In addition to numerous non-fiction books, the fight of the Nez Percé also served as material and basis for fiction authors, for example Werner J. Egli for his novel When the Fires went out . In addition, the Nez Percé War is also the subject of film adaptations, such as the production for American television under the German title Ich kampf wieder . Joseph is played by Ned Romero, General Howard by James Whitmore , and Sam Elliott plays Howard's aide Charles Wood.

See also

literature

- John A. Carpenter: Sword and Olive Branch - Oliver Otis Howard , Fordham University Press, New York, 1999 (first edition 1964), ISBN 978-0-8232-1988-9 . Carpenter († 1978), who taught in New York, wrote a biography of Howard, who died in 1909, which proves his strengths and which turned against biographies that criticized Howard sharply.

- Jerome A Greene: Nez Perce Summer, 1877: The US Army and the Nee-Mee-Poo Crisis. Helena, Montana 2000, ISBN 0-917298-82-9 . Fundamental work of the national park historian ( online ).

- Francis Haines: Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce Warriors , Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 45.1 January 1954, pp. 1-7.

- Chief Joseph and William H. Hare, An Indian's Views of Indian Affairs , North American Review, April 1879, pp. 412-434, available online at cornell.edu .

- Oliver Otis Howard, The True Story of the Wallowa Campaign , North American Review, July 1879, pp. 53-65, available online at cornell.edu .

- Alvin M. Josephy Jr .: The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest , Yale University 1965, again: New York: Mariner, 1997, ISBN 978-0395850114 . One of the publications that supported the abandonment of the termination policy that had begun in 1961 (cf. American Indian policy ).

- Duncan MacDonald, Wilfried Homann: There will be many tears. The Nez Percé campaign in 1877 , translation from 2002. ISBN 3-89510-084-6 . MacDonald was in Canada as an interpreter in negotiations with White Bird. He himself was descended from Schotten and Nez Perce. On this basis, he wrote a report on the course of the war for a newspaper.

- Stuart Christie: When Warriors and Poachers Trade: Duncan MacDonald's Through Nez Perce Eyes and the Birth of Separate Sovereignties During the Nimiipu War of 1877 , in: Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 12.1 (2011). Discusses u. a. the question of whether the Nez Perce War is at the beginning of the sovereignty debate of the indigenous peoples of North America, which continues to this day.

- Charles Erskine Scott Wood: Chief Joseph, the Nez Percé , The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. Vol. 28 (May-October 1884), pp. 136-142, available online at cornell.edu .

- Lynn N. and Dennis W. Baird: In Nez Perce Country. Accounts of the Bitterroots and the Clearwater after Lewis and Clark , University of Idaho Library, 2003, ISBN 0-89301-503-2 . Best representation for the period between around 1800 and 1877, also with z. In part, previously unpublished sources were enriched.

Web links

- Nez Perce Campaign 1877 - Description of the campaign

- The Flight of the Nez Perce - A Timeline - Timeline

Remarks

- ^ Probably first by John Stuart Wasson: The Nimipu War , in: Indian Historian 3,4 (1970) 5-9 so designated.

- ↑ The consecutive naming of the Nez Percé follows the literature and therefore uses English for some tribal members and Indian names for others. In the case of Indians, who are predominantly referred to by their English name in the literature, the Indian name is also mentioned when they are first mentioned; the spelling follows Josephy Jr., The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the American Northwest .

- ↑ Information about the length covered by the Nez Percé varies; Bruce Hampton, Children of Grace - The Nez Perce War of 1877 , University of Nebraska Press, 1994, pp. 301f., Lists a distance of "about 1200 miles," Handbook of North American Indians , Vol. 12, pp. 435, speaks of 1300 miles. Further details are sometimes even higher.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , pp. 5f.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , pp. 8ff.

- ^ Robert Marshall Utley: Nez Percé Bid for Freedom , in: Ders .: Frontier Regulars. The United States Army and the Indian, 1866-1891 , 1973, reprinted New York 1984, pp. 296-320, here: p. 297.

- ^ Wood, Chief Joseph, the Nez Perce , p. 135.

- ↑ All the chiefs of the Nez Percé, whose land was within the new reservation, signed the contract. Of the groups whose land was outside the new reservation, only two Indians named Jason and Timothy signed, although they were allowed to own their houses; see Josephy Jr., The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest , p. 429.

- ^ Josephy Jr, The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the American Northwest , pp. 410-430. For the text of the treaty, see the website of the Center for Columbia River History: Treaty with the Nez Perce Indians, June 9, 1863 .

- ^ Carpenter, Sword and Olive Branch , p. 246

- ^ Carpenter, Sword to Olive Branch , p. 245.

- ^ Robert Marshall Utley: Nez Percé Bid for Freedom , in: Ders .: Frontier Regulars. The United States Army and the Indian, 1866-1891 , 1973, reprint New York 1984, pp. 296-320, here: pp. 297f.

- ↑ see also Green, Nez Perce Summer , p. 108.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 77.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 105.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 250.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , pp. 3, pp. 106f.

- ^ Haines, Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce Warriors , p. 1.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 29.

- ↑ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , 106–10. Josephy Jr., The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the American Northwest , p. 556.

- ^ Haines, Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce Warriors , p. 4.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer, 1877 , p. 123.

- ^ Josephy Jr., The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest , p. 574.

- ↑ Josephy Jr., The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest , 613

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 266.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 237.

- ^ Chief Joseph and William H. Hare, An Indian's View of Indian Affairs , p. 423.

- ^ Chief Joseph and William H. Hare, An Indian's View of Indian Affairs , 430.

- ↑ The closest and probably best source for this is John D. McDermott: The Battle of White Bird Canyon and the Beginning of the Nez Perce War , ed. By the Idaho State Historical Society, Boise, Idaho 1878, reissued 1978, again under the Title: Forlorn Hope. The Nez Perce Victory at White Bird Canyon , Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Press 2003.

- ^ Haines, Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce Warriors , p. 2.

- ↑ Lucullus Virgil McWorther and Yellow Wolf: Yellow Wolf- his own story , 7th edition, Caxton Press, Idaho, 2000, pp. 60f.

- ^ Carpenter, Sword and Olive Branch , p. 250.

- ↑ How many Warriors Looking Glass had already joined the fugitive groups at this point, and whether this was done with warlike intentions is not clear. Josephy Jr., The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the American Northwest , p. 534, suggests that Howard thought there were 40 warriors, but believes that this number was, intentionally or accidentally, exaggerated by Howard's scouts. Greene in Nez Perce Summer , p. 51, speaks of at least 20 men, but also points out that these could simply be visitors.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , pp. 50ff.

- ^ Josephy Jr., The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest , pp. 535ff.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 56.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , pp. 61ff.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 95

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 93

- ^ Carpenter, Sword and Olive Branch , p. 251

- ^ Josephy Jr., The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest , pp. 567f.

- ^ Josephy Jr., The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest , p. 568

- ^ Josephy Jr., The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest , p. 574.

- ^ Chief Joseph and William H. Hare, An Indian's View of Indian Affairs , p. 426

- ^ Carpenter, Sword and Olive Branch , pp. 252 and 255.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 138.

- ↑ Green, Nez Perce Summer , p. 144.

- ↑ Carpenter, Sword and Olive Branch , pp. 255f.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , pp. 231f.

- ^ J. Diane Pearson: The Nez Perces in the Indian territory: Nimiipuu survival , University of Oklahoma Press, 2008, pp. 40f.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer, p. 317

- ^ J. Diane Pearson: The Nez Perces in the Indian territory: Nimiipuu survival , University of Oklahoma Press, 2008, p. 41

- ↑ Carpenter, Sword and Olive Branch , pp. 258f.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 338.

- ↑ Reproduced inter alia in Wood, Chief Joseph, the Nez Perce , p. 141.

- ^ Carpenter, Sword and Olive Branch , p. 261.

- ↑ Wood, Chief Joseph, the Nez Perce , 142.

- ↑ for the numbers see: Lewis-Clark.org: Forty Miles from Freedom

- ↑ Carpenter, Sword and Olive Branch , pp. 262f.

- ↑ Chief Joseph and William H. Hare, An Indian's View of Indian Affairs , pp. 419f.

- ^ Chief Joseph and William H. Hare, An Indian's View of Indian Affairs , 419

- ^ Chief Joseph and William H. Hare, An Indian's View of Indian Affairs , p. 429.

- ^ Carpenter, Sword and Olive Branch , p. 264.

- ^ Chief Joseph and William H. Hare, An Indian's View of Indian Affairs , 430

- ^ Howard, The True Story of the Wallowa Campaign , p. 54.

- ^ Howard, The True Story of the Wallowa Campaign , p. 54.

- ^ Howard, The True Story of the Wallowa Campaign , p. 64.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , pp. 340f.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , pp. 343f.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 349

- ^ Siegfried Augustin : The history of the Indians , Nymphenburger, 1995, p. 423, ISBN 3-485-00736-6 .

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 358.

- ↑ FLM: The Nez Perce War , The Galaxy, Volume 24, Issue 6, pp. 817–827, available online at cornell.edu

- ^ Helen Hunt Jackson, A Century of Dishonor , p. 132.

- ^ Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 337.

- ^ Mark Q. Sutton: An Introduction to Native North America , California State University 2003, pp. 116f.

- ^ Wood: Chief Joseph, the Nez Perce , p. 135.

- ↑ FLM: The Nez Perce War , The Galaxy 24,6, p. 823.

- ^ Josephy Jr., The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest , p. 430.

- ↑ Quoted by Alvin Josephy Jr., Foreword to Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. XI.

- ^ Wood: Chief Joseph, the Nez Perce , p. 135.

- ^ Howard, "Nez Perce Joseph," 146

- ^ Haines, Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce Warriors , p. 1; Merle W. Mells: The Nez Perce and their War , Pacific Northwest Quarterly , 55.1, January 1964, pp. 35-37

- ^ Haines, Joseph and the Nez Perce Warriors , p. 7

- ^ Haines, Joseph and the Nez Perce Warriors , p. 7.

- ↑ John A. Carpenter: General Howard and the Nez Perce War of 1877 , Pacific Northwest Quarterly, April 49, 1958, pp. 129-145; P. 144f. Similarly, Greene, Nez Perce Summer , p. 327.

- ↑ The book contains, unusual for a novel, a detailed bibliography on the facts