Air Force Research Laboratory

| Air Force Research Laboratory | |

|---|---|

Emblem of AFRL | |

| Active | October 1997-Present |

| Country | United States |

| Branch | Air Force |

| Type | Research and development |

| Size | 4,200 civilian 1,200 military (2006) |

| Part of | Air Force Materiel Command |

| Garrison/HQ | Wright-Patterson Air Force Base |

| Commanders | |

| Commander | Maj Gen Curtis Bedke |

| Vice-Commander | Col David Glade |

The United States Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) is a scientific research organization operated by the United States Air Force Materiel Command dedicated to the development of warfighting technologies.[1] The Laboratory controls the entire Air Force science and technology research budget which was $2.4 billion in 2006.[2]

Mission Statement

AFRL's published mission statement is[3]:

- Leading the discovery, development and integration of affordable aerospace warfighting technologies.

- Planning and executing the Air Force science and technology program.

- Provide warfighting capabilities to United States air, space and cyberspace forces.

History

The path to a consolidated Air Force Research Laboratory began with the passage of the Goldwater-Nichols Act. The Act was designed to streamline the use of resources by the Department of Defense.[4] In addition to this Act, the end of the Cold War began a period of budgetary and personnel reductions within the armed forces in preparation for a "stand-down" transition out of readiness for a global war.[5] Prior to 1990, the Air Force Laboratory system spread research out into 13 different laboratories and the Rome Air Development Center which each reported up two separate chains of command for personnel and budgetary purposes. Bowing to the constraints of a reduced budget and personnel, the Air Force merged the existing research laboratories into four "superlabs" in December 1990.[6] During this same time period was when the Air Force Systems Command and Air Force Logistics Command merged to form Air Force Materiel Command in July 1992.[7]

| Pre-Merger | Post-Merger |

|---|---|

| Weapons Laboratory, Kirtland AFB, NM | Phillips Laboratory Kirtland AFB |

| Geophysics Laboratory, Hanscom AFB, MA | |

| Astronautics Laboratory, Edwards AFB, CA | |

| Avionics Laboratory, Wright-Patterson AFB, OH | Wright Laboratory Wright-Patterson AFB |

| Electronics Technology Laboratory, Wright-Patterson AFB, OH | |

| Flight Dynamics Laboratory, Wright-Patterson AFB, OH | |

| Material Laboratory, Wright-Patterson AFB, OH | |

| Aero Propulsion and Power Laboratory, Wright-Patterson AFB, OH | |

| Armament Laboratory, Eglin AFB, FL | |

| Rome Air Development Center, Griffiss AFB, NY | Rome Laboratory Griffiss AFB, NY |

| Human Resources Laboratory, Brooks AFB, TX | Armstrong Laboratory Brooks AFB, TX |

| Harry G. Armstrong Aerospace Medical Research Laboratory, Wright-Patterson AFB, OH | |

| Drug Testing Laboratory, Brooks AFB, TX | |

| Occupational and Environmental Health Laboratory, Brooks AFB, TX |

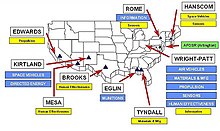

While the initial consolidation of Air Force laboratories reduced overhead and budgetary pressure, another push towards a unified laboratory structure came in the form of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1996, Section 277. This section instructed the Department of Defense to produce a five-year plan for consolidation and restructuring of all defense laboratories.[9] The currently existing laboratory structure was created in October 1997 through the consolidation of Phillips Laboratory headquartered in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Wright Laboratory in Dayton, Ohio, Rome Laboratory (formerly Rome Air Development Center) in Rome, New York, and Armstrong Laboratory in San Antonio, Texas and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR).[10] The single laboratory concept was developed and championed by Maj Gen Richard Paul, then Director of Science & Technology for AFMC and Gen Henry Viccellio Jr, then Commander, AFMC.[11]

With the merger of the laboratories into a single entity, the history offices at each site ceased to maintain independent histories and all history functions were transferred to a central History Office located at AFRL HQ at Wright-Patterson AFB.[12] In homage to the predecessor laboratories, the new organization named four of the research sites after the laboratories and assured that each laboratories' history would be preserved as inactivated units.[13]

Organization

The laboratory is divided into 8 Technical Directorates, one wing, and the Office of Scientific Research based on different areas of research. AFOSR is primarily a funding body for external research while the other directorates perform research in-house or under contract to external entities.[14]

A directorate is roughly equivalent to a military wing. Each directorate is composed of a number of divisions and typically has at least three support divisions in addition to its research divisions.[15] The Operations and Integration Division provides the directorate with well-conceived and executed business computing, human resource management, and business development services.[16] The Financial Management Division manages the financial resources[17] and the Procurement Division provides an in-house contracting capability. The support divisions at any given location frequently work together to minimize overhead at any given research site. Each division is then further broken down into branches, roughly equivalent to a military squadron.

Superimposed on the overall AFRL structure are the eight detachments. Each detachment is composed of the AFRL military personnel at any given geographical location.[18] For example, the personnel at Wright-Patterson AFB are all part of Detachment 1. Each detachment will typically also have a unit commander separate from the directorate and division structure.

Air Force Office of Scientific Research

- Arlington, Virginia

- London, United Kingdom

- Tokyo, Japan

AFRL's contribution to research is "by investing in basic research efforts for the Air Force in relevant scientific areas."[14] This is done with private industry and academia, as well as with other organizations in the Department of Defense and AFRL. The current Director of AFOSR is Brendan Godfrey.[19]

AFOSR's research is organized into three scientific directorates: the Aerospace, Chemical, and Material Sciences Directorate, the Mathematics, Information, and Life Sciences Directorate, and the Physics and Electronics Directorate.[20] Each directorate funds research activities which it believes will enable the technological superiority of the USAF.

AFOSR also maintains two foreign technology offices located in the UK and Japan. These overseas offices coordinate with the international scientific and engineering community to allow for better collaboration between the community and Air Force personnel.[14]

Air Vehicles Directorate

The Air Vehicles Directorate's vision is on "technology investments that support cost-effective, survivable aerospace vehicles capable of accurate and quick delivery of a variety of future weapons or cargo anywhere in the world." [3] Typically, the Directorate researches areas related to aerodynamics and controls for use in aircraft, while air vehicle propulsion system research is handled by the Propulsion Directorate.[citation needed] Historically, research performed has contributed to the development of stealth technology, lifting body aircraft, and reconfigurable wing surfaces.[citation needed] The current Director of the Air Vehicles Directorate is Col John Wissler.[19]

The Air Vehicles Directorate has previously collaborated with NASA in the X-24 project to research concepts associated with lifting body type aircraft which contributed to the development of the Space Shuttle's unpowered re-entry and landing technique.[citation needed] More recently, the Directorate is also collaborating with NASA Langley Research Center on the Boeing X-48 project to study characteristics of blended wing body type aircraft;[21] in 2002, the Directorate initiated the X-53 Active Aeroelastic Wing program in cooperation with NASA Dryden Flight Research Center and Boeing Phantom Works to research ways to make more efficient use of the wing's planform during high-speed maneuvers.[22] The Directorate is also a collaborator with DARPA, and the Space Vehicles Directorate on the Force Application and Launch from Continental United States (FALCON) program, which includes the HTV-3X "Blackswift" hypersonic flight demonstration vehicle.[23]

Directed Energy Directorate

- Kirtland Air Force Base, New Mexico

- Maui, Hawaii

- White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico

The mission of the Directed Energy Directorate "is the Air Force's center of excellence for high power microwave technology and the Department of Defense's center of expertise for laser development, including semiconductor, gas, chemical and solid-state lasers."[3] The current Director of the Directed Energy Directorate is Susan Thornton.[19]

The Starfire Optical Range at Kirtland AFB, North Oscura Peak on White Sands Missile Range, and the Air Force Maui Optical and Supercomputing observatory (AMOS) are also operated by divisions of the Directed Energy Directorate in addition to their facilities at the Directorate's headquarters at Kirtland AFB.[citation needed] The Starfire Optical Range is used to research various topics of advanced tracking using lasers as well as studies of atmospheric physics which examines atmospheric effects which can distort laser beams.[24] North Oscura Peak is used to research the various technologies necessary to facilitate successful tracking and destruction of an incoming missile via a laser and is used frequently for laser-based missile defense tests.[25] AMOS provides computational resources to AFRL, Department of Defense as well as other agencies of the US Government.[26]

Directed Energy projects typically fall into two categories: laser and microwave. Laser projects range from completely non-lethal targeting lasers to dazzlers such as the Saber 203 used by US forces during the Somali Civil War and the more recent PHaSR dazzler[27] to powerful missile defense lasers such as the chemical oxygen iodine laser (COIL) used in the YAL-1A project now led by the Missile Defense Agency.[citation needed] Microwave technologies are being advanced for use against both electronics and personnel. One example of an anti-personnel microwave project is the "less-than-lethal" Active Denial System which uses high powered microwaves to penetrate less than a millimeter into the target's skin where the nerve endings are located.[citation needed]

There have been a number of human rights controversies involving the products of directed energy research.[citation needed] Going back as far as 1995, there were arguments that laser dazzlers could potentially cause permanent blindness in targets.[citation needed] The Human Rights Watch proposed that all tactical laser weapons should be scrapped and research stopped by all interested governments.[28] These same concerns were revived with the announcement of the PHaSR[clarification needed] project. The Active Denial System has also been the target of Amnesty International as well as, less directly, a United Nations special rapporteur.[29]

711th Human Performance Wing

- Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio

- Brooks City-Base, Texas

- Mesa Research Site, Arizona

In March 2008, the Human Effectiveness Directorate was merged with the USAF School of Aerospace Medicine and the Human Performance Integration Directorate to form the 711th Human Performance Wing.[30] In its vision statement, the Directorate includes the goals of "integrating personnel with systems technology," and "protecting the force." Towards fulfilling those goals, the 711th HPW performs research to "define human capabilities, vulnerabilities, and effectiveness." The current Director of the 711th is Thomas Wells.[19] One practical application of its work is ensuring and advancing the safety of ejection systems for pilots[31], and it has been working to protect airmen since 1931.[citation needed] Advanced manikins equipped with numerous sensors are used to establish injury thresholds and stress tolerances necessary for the design and implementation of aircraft and their systems.[citation needed] With the increasing number of females in the Air Force ranks, anthropometry is of greater import now than ever, and 711th's WB4 'whole-body scanner' enables swift and accurate acquisition of anthropometric data which may be used to design pilot equipment with a better fit for comfort and safety.[32]

Information Directorate

- Rome Research Site, New York

The mission of the Information Directorate is "to lead the discovery, development, and integration of affordable warfighting information technologies for our air, space, and cyberspace force." [33] The current Director of the Information Directorate is Donald Hanson.[19] The Directorate is based at the site of the former Rome Air Development Center which was merged into AFRL in 1997.[citation needed] In addition to the supporting divisions, there are four research divisions in the Information Directorate: Information and Intelligence Exploitation, Information Grid, Information Systems, and Advanced Computing.[34] Each division contributes to the overall goal of enhancing the sensing and information handling capabilities of deployed Air Force personnel.[citation needed]

The Information Directorate has contributed research to a number of technologies which have been deployed in the field. These projects include collaboration with other agencies in the development of ARPANET, the predecessor of the Internet, as well as technologies used in the Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System which is a key aspect of theater command and control for combat commanders.[33] The Directorate also collaborated with the Department of Justice performing research on voice stress analysis technologies.[35]

Materials and Manufacturing Directorate

- Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio

- Tyndall Air Force Base, Florida

The AFRL Materials and Manufacturing Directorate develops materials, processes, and advanced manufacturing technologies for aerospace systems and their components. The Directorate works to improve Air Force capabilities in manufacturing and materials research technologies.[36]The current Director of the Materials and Manufacturing Directorate is David Walker.[19] In 2006, an AFRL project to improve the strength of C-17 landing gear doors using composite materials was completed in cooperation with Boeing.[37] The AFRL has also been conducting research into friction stir welding for use in attaching difficult to weld materials together.[38] In 2008, the Air Force announced that the Directorate had developed a method of using fabric made of fiber optic material in a friend or foe identification system.[39]

Munitions Directorate

- Eglin Air Force Base, Florida

The mission of the Munitions Directorate is to "develop, demonstrate and transition science and technology for air-launched munitions for defeating ground fixed, mobile/relocatable, air and space targets to assure pre-eminence of U.S. air and space forces."[3] The current Director of the Munitions Directorate is Col Kirk Kloeppel.[19]

The Munitions Directorate is the Air Force's primary research and development organization for aircraft-based projectile weaponry, such as bombs and missiles.[citation needed] Their work includes munition guidance systems and advanced explosives. Notable projects which have been made public include the GBU-28 "bunker-buster" bomb which debuted during the 1991 Persian Gulf War in Iraq.[40] The Directorate also developed the GBU-43/B Massive Ordnance Air Blast bomb which was deployed during the 2003 invasion of Iraq for Operation Iraqi Freedom.[citation needed] This bomb produces a blast so big it was confused with a nuclear detonation by nearly every group which viewed the demonstration video.[citation needed]

Propulsion Directorate

- Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio

- Edwards Air Force Base, California

The mission of the Propulsion Directorate is "to create and transition propulsion and power technology for military dominance of air and space."[41] The current Director of the Propulsion Directorate is William Borger.[19] The Propulsion Directorate has historically been the largest directorate within AFRL.[citation needed] Research areas range from experimental rocket propulsion to developing thrust vectoring technologies used in the F119 engines of the F-22 Raptor fighter.[citation needed] At Edwards, the Directorate's test area is located east of Rogers Lake.

The Propulsion Directorate at AFRL was formed through the merger of the aerospace propulsion section at Wright Laboratory and the space propulsion section at Phillips Laboratory.[citation needed] Each sections, both before and after the merger, have played significant roles in past and present propulsion systems. Prior to the development of Project Apollo by NASA, the Air Force worked on the development and testing of the F-1 rocket engine used in the Saturn V rocket.[citation needed] The facilities for testing rockets are frequently used for testing new rocket engines including the RS-68 engine developed for use on the Delta IV Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle.[citation needed] The space propulsion area also develops technologies for use in satellites on-orbit to alter their orbits. An AFRL developed test electric propulsion system was flown on the ARGOS satellite in 1999.[citation needed]

The Directorate currently manages the X-51A program, which is developing a scramjet demonstration vehicle.[42] In January 2008, the Directorate's experimental pulse detonation engine successfully completed it's first test flight on a significantly modified Scaled Composites Long-EZ aircraft.[43]

Sensors Directorate

- Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio

- Rome Research Site, New York

- Hanscom Air Force Base, Massachusetts

The Sensors Directorate's vision is to provide a full range of air and space sensors, networked to the warfighter, providing a complete and timely picture of the battlespace enabling precision targeting of the enemy and protection friendly air and space assets.[citation needed] Its core technology areas include: radar, active and passive electro-optical targeting systems, navigation aids, automatic target recognition, sensor fusion, threat warning and threat countermeasures.[3] The current Director of the Sensor Directorate is David Jerome.[19] The divisions currently located at Hanscom AFB and Rome Research Site are scheduled to move to Wright-Patterson AFB under the Defense Base Realignment and Closure, 2005 Commission.[citation needed]

The Directorate is composed of 7 divisions which research a variety of sensor technologies.[citation needed] They have contributed significantly to the Integrated Structure is Sensor (ISIS) project managed by DARPA which is a project to develop a missile tracking airship.[44] In June 2008, the Air Force announced that scientists working for the Sensors Directorate had demonstrated transparent transistors. These could eventually be used to develop technologies such as "video image displays and coatings for windows, visors and windshields; electrical interconnects for future integrated multi-mode, remote sensing, focal plane arrays; high-speed microwave devices and circuits for telecommunications and radar transceivers; and semi-transparent, touch-sensitive screens for emerging multi-touch interface technologies."[45]

Space Vehicles Directorate

The mission of the Space Vehicles Directorate is to develop and transition space technologies for more effective, more affordable warfighter missions.[3] In addition to the Directorate headquarters at Kirtland Air Force Base, New Mexico and an additional research facility at Hanscom Air Force Base, Massachusetts, the High Frequency Active Auroral Research Program (HAARP) located near Gakona, Alaska is also jointly operated by the Space Vehicles Directorate as well as DARPA, the Office of Naval Research (ONR), the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) and universities to conduct ionospheric research.[46] The current Director of the Space Vehicles Directorate is Col Robert S. Green.[19] The Battlespace Environment division currently located at Hanscom AFB is scheduled to move to Kirtland AFB under the Defense Base Realignment and Closure, 2005 Commission.[47]

The IBM RAD6000 radiation hardened single board computer, now produced by BAE Systems, was initially developed in a collaboration with the Space Electronics and Protection Branch and IBM Federal Systems and is now used on nearly 200 satellites and robotic spacecraft, including on the twin Mars Exploration Rovers— Spirit and Opportunity.[48] In November 2005, the AFRL XSS-11 satellite demonstrator received Popular Science's "Best of What's New" award in the Aviation and Space category. [49] The Space Vehicles Directorate is also a leading collaborator in the Department of Defense Operationally Responsive Space Office's Tactical Satellite Program and served as program manager for the development of TacSat-2, TacSat-3, and is current program manager for the development of TacSat-5.[50] They also have contributed experimental sensors to TacSat-1 and TacSat-4 which were managed by the NRL's Center for Space Technology.[51]

The University Nanosatellite Program, a satellite design and fabrication competition for universities jointly administered by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, AFOSR, AFRL, and the Air Force Space and Missile Systems Center, is also managed by the Space Vehicles Directorate's Spacecraft Technology division.[52] The fourth iteration of the competition was completed in March 2007 with the selection of Cornell University's CUSat as the winner.[53] Previous winners of the competition were University of Texas at Austin's Formation Autonomy Spacecraft with Thrust, Relnav, Attitude, and Crosslink (FASTRAC) for Nanosat-3 [54] and the joint 3 Corner Satellite (3CS) project by the University of Colorado at Boulder, Arizona State University and New Mexico State University for Nanosat-2.[55] As of July 2008[update], only the 3CS spacecraft has launched, however FASTRAC has a launch tentatively scheduled for December 2009.[56]

The Directorate has indirectly faced significant controversy over the HAARP project which is jointly managed by the Battlespace Environment division with the Naval Research Laboratory and Naval Office of Scientific Research.[57] While the project claims to be developed only for studying the effects of ionospheric disruption on communications, navigation, and power systems, many suspect it of being developed as a prototype for a "Star Wars" type of weapon system.[58] Still others are more concerned with the environmental impact to migratory birds of beaming thousands of watts of power into the atmosphere.[59] However one thing which all sides can agree on is the shroud of secrecy around the project and the government's attempts to cover up information.[60]

References

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: http://www.afrl.af.mil

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: http://www.afrl.af.mil

- ^ US Air Force. "Air Force Research Laboratory". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ Department of Defense Inspector General (2007-09-28). "Contracting Practices at Air Force Laboratory Facilities". Department of Defense. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ a b c d e f US Air Force. "Factsheets : Air Force Research Laboratory". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

- ^ United States Congress (1986-04-08). "S. 2295. To Amend Title 10, United States Code, to Reorganize and Strengthen Certain Elements of the Department of Defense, to Improve the Military Advice Provided the President, the National Security Council, and the Secretary of Defense, to Enhance the Effectiveness of Military Operations, to Increase Attention to the Formulation of Strategy and to Contingency Planning, to Provide for the More Efficient Use of Resources, to Strengthen Civilian Authority in the Department of Defense, and for Other Purposes" (PDF). 99th Congress, Second Session. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ Duffner, Robert (2000). Science and technology: the making of the Air Force Research Laboratory (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University Press. pp. pg 9. ISBN 1-58566-085-X. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Duffner 2000: 11

- ^ US Air Force. "Factsheets : Air Force Materiel Command". AFMC. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ Duffner 2000: 12

- ^ United States Congress. "S.1124 National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1996, Section 277". 104th Congress, Second Session. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ Duffner 2000: 117

- ^ Duffner 2000: 38

- ^ Duffner 2000: 257

- ^ Duffner 2000: 261

- ^ a b c US Air Force. "Factsheets : AFOSR : About - Mission". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ Duffner 2000: 190

- ^ US Air Force. "Fact Sheets : AFRL/RYO (Integration & Operations)". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ US Air Force. "Fact Sheets : AFRL/RYF (Financial Management)". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ Duffner 2000: 262

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j US Air Force. "Air Force Research Laboratory Biographies". AFMC. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ^ US Air Force. "AFOSR Fact Sheet". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ "Boeing Flies Blended Wing Body Research Aircraft" (HTML). Boeing. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ Cole, William. "Let's Twist Again! : Technology that enables wing 'warping' rolled out at Dryden" (HTML). Boeing Frontiers Online. Boeing. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ Kleiman, Michael (2006-01-27). "High-speed air vehicles designed for rapid global reach". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ Blaylock, Eva (2006-12-01). "Lasers, microwave technology among AFRL's Directed Energy Directorate's works". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ US Air Force. "North Oscura Peak Factsheet" (PDF). AFRL. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ US Air Force. "About AMOS". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ Knight, Will (2005-11-07). "US military sets laser PHASRs to stun". New Scientist. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ^ "U.S. Blinding Laser Weapons". Human Rights Watch Arms Project. Human Rights Watch. 1995. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wright, Steve (2006-10-05). "Targeting the pain business". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- ^ US Air Force. "711th Human Performance Wing". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ US Air Force (1999). "Air Force Research Laboratories Success Stories: A Review of 1997/1998" (PDF). AFRL. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cyberware. "Wright-Patterson to Use the First Whole Body Scanner" (HTML). Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ a b US Air Force. "AFRL Information Directorate Overview" (PPT). AFRL. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ US Air Force. "Factsheets : AFRL/RI Organizations". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ^ Air Force News Service (1997-09-23). "Voice stress analysis evaluation begins" (HTML). Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ^ US Air Force. "AFRL Materials and Manufacturing Directorate". AFRL. Archived from the original on 2007-04-29. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ US Air Force. "AFRL Improves Durability For C-17 Main Landing Gear Doors". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ US Air Force. "Friction Stir Welding Provides Advantages Over Conventional Fusion Welding Process". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ Cooper, Mindy (2008-01-24). "Air Force develops friend vs. foe identification system". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ AFRL. "Factsheets : AFRL Munitions Directorate History". US Air Force. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ^ US Air Force. "Introduction to Air Force Research Laboratory Propulsion Directorate" (PDF). AFRL. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ Boeing (2007-06-01). "Successful Design Review and Engine Test Bring Boeing X-51A Closer to Flight". Retrieved 2008-06-14.

- ^ Barr, Larine. "Pulsed detonation engine flies into history" (HTML). AFRL. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ Staff Writers (2006-05-22). "AFRL Awards ISIS Contracts To Northrup Grumman". Space Daily. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ Lachance, Molly (2008-06-19). "Air Force Scientists Develop Transparent Transistors" (HTML). Space Mart. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ University of Alaska. "HAARP Fact Sheet". Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ^ Principi, Anthony J. (2005-09-08). "2005 Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission Report: Volume 1" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-07-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fordahl, Matthew (2004-01-23). "Software on Mars rovers 'space qualified'". Associated Press. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ^ "Experimental Satellite System 11 (XSS-11)". Popular Science. 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-05-27. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2006-12-12 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Doyne, Col Tom (2007-04-23). "ORS and TacSat Activities Including the Emerging ORS Enterprise" (PDF). 5th AIAA Responsive Space Conference. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Raymond, Col Jay (2005-04-26). "A TacSat Update and the ORS/JWS Standard Bus" (PDF). 3rd AIAA Responsive Space Conference. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ US Air Force. "University Nanosatellite Program". AFRL. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ Staff Writers (2007-04-04). "Cornell University Chosen To Build Nanosat-4 Flight Experiment". Space Daily. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ^ Torres, Juliana (2005-01-21). "Students' satellites win right to space flight". The Daily Texan. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "Three Corner Satellite". NASA. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (2008-06-26). "FASTRAC Satellites Get Updated Software, New Antennas". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ Begich, Nick (1995). Angels Don't Play This HAARP: Advances in Tesla Technology. Earthpulse Press. ISBN 0-96488-120-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Smith, Jerry E. (1998). HAARP: The Ultimate Weapon of The Conspiracy. Adventures Unlimited Press. pp. pp. 21-22. ISBN 0-93281-353-4. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Streep, Abe (2008-06-18). "Scientific Tool or Weapon of Conspiracy?". Popular Science. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ^ Smith 1998: 16

External links

- Air Force Research Laboratory Homepage (official)